Should Howie Carr Have Helped a Killer Profit Off His Crimes?

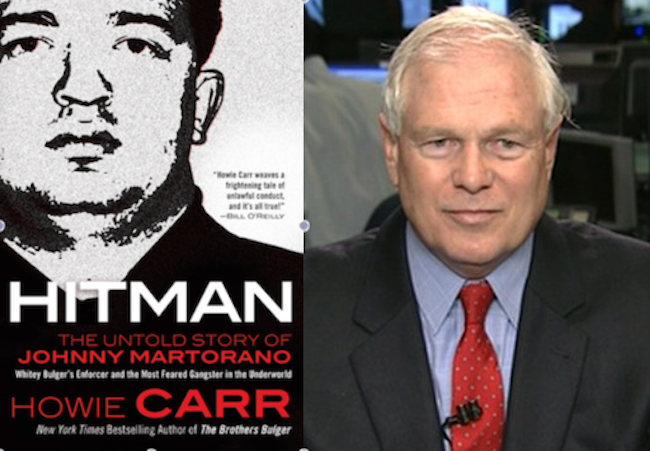

Among the most incredible aspects of Johnny Martarano’s testimony in the trial of Whitey Bulger is that an admitted murderer of 20 people managed not only to walk free after 12 years in prison, but to profit from the sale of his odious life story. That’s thanks in part to everyone’s favorite Boston Herald columnist Howie Carr. Martarano testified in court Monday that he split a $110,000 advance for Carr’s book about him, Hitman, and has made $20,000 in royalties since. He also sold film rights to his life story for $250,000. A blogger for Democratic Blue Mass Group was incensed:

So every time Howie promotes the book on WRKO or in his Herald column (which he did today), it helps line the pockets of this monster. I intended to buy the book at some time, but now that I know some of my money will be going to this creep (I mean Martorano in this case), I won’t be buying it.

Of course it is no surprise that Carr is a two-face hypocrite, but entering into a business arrangement to enrich a cold-blooded killer! And shame on Entercom and the Boston Herald for allowing their companies to be promotional platforms for one of the devil’s henchmen.

Media blogger Dan Kennedy also raised his eyebrows, sarcastically referring to Carr as “that paragon of virtue.”

There are, of course, several people aside from Howie Carr that helped bring about this state of affairs. Chief among them the federal authorities who so wanted to nail Whitey Bulger, they offered a mass murderer a laughably light sentence. Others have wondered why there aren’t any laws to prevent criminals from profiting off their crimes. So called “Son of Sam” laws have, of course, existed but many of them have failed to pass judicial review. When the Massachusetts legislature considered one that would divert profits to victims, the state’s Supreme Judicial Court said it would violate free speech protections. In a unanimous decision, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled a New York law unconstitutional on grounds that it was too broad. The court also made the point that banning all criminals from selling their stories isn’t necessarily always in the public interest. A Son of Sam law might have prevented The Autobiography of Malcolm X or Thoreau’s Civil Disobedience, both of which, you’d have to admit, serve some value to readers.

Carr must have thought that Martorano’s story was compelling enough that it was worth entering into an agreement with him. (Not a bad bet, based on the rapt attention we’re all paying to his testimony this week.) Sure, a killer profits, but the public hears about his crimes and learns something about the Boston organized crime scene in the 20th century. Is that a worthy tradeoff? Hitman probably doesn’t serve up the same service to society as Thoreau, but does it provide us enough that it’s worth enriching a criminal? That’s a blurred line for which the right answer probably depends on the value judgement of the beholder.

Still, Carr’s critics might have hoped that even as he told the story, he’d maintain a strong disdain for the killer. Even today, he notes that Martorano’s career is “nothing to be proud of” but he could be accused of taking a softer tone with him than with, say, Bulger. He seems to have had a bit more trouble maintaining an emotional distance from his partner, Martorano. In the acknowledgements for Hitman he writes:

We spent hours together much of it in the city room of the Boston Herald early Sunday mornings. He talked, I listened. Everything that has been said about his memory is true. Not only does he have a near-photographic recall of details, but he’s also a first class raconteur. As one of my Herald colleagues who got to know Johnny on those Sunday mornings put it, “If only he weren’t so damned likeable.”

Yeah, if only.