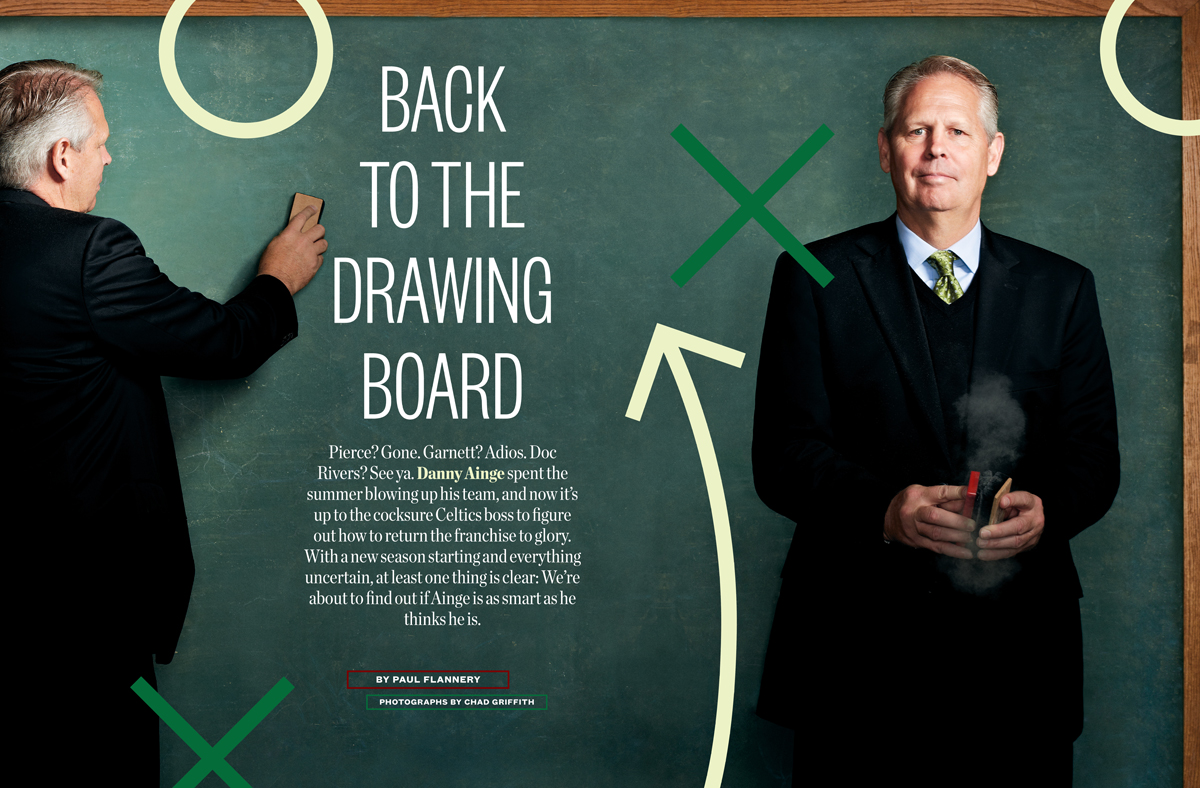

Danny Ainge Goes Back to the Drawing Board

Photographs by Chad Griffith

Here’s the thing to understand about Danny Ainge’s master plan: It doesn’t exist. There are no secret step-by-step memos hidden in his office at the Celtics’ Waltham practice facility, nor is there a blueprint-filled safe. What does exist in his office is a window, through which Ainge can see down onto the practice court. On this particular August day, when he looks out, he does not see Rajon Rondo, since the star point guard is still sidelined with a torn ACL. And he certainly does not see Kevin Garnett or Paul Pierce. Ainge, the Celtics’ president of basketball operations, shipped the franchise icons to Brooklyn earlier in the summer. Instead, Ainge watches a bunch of unproven youngsters and veteran journeymen. To Celtics fans this season, they’ll most likely look like an unholy mess. To Ainge right now, they look like poker chips.

Ainge is not particularly sentimental, but scanning his office, it’s hard to miss the handful of reminders of the not-so-distant past. A large 2008 championship banner hangs on the wall behind him, while a pair of unpopped champagne bottles from the celebration stand sentry beside the championship ring gleaming from the front of his desk.

That team was Ainge’s crowning achievement as an executive. It took five years of dealing and scheming to get sure-fire Hall of Famers Ray Allen and Garnett to join Pierce and lead the Celtics to their first championship in 22 years. It took him less than a week to tear it all down.

The machinations started in late June, when Ainge released coach Doc Rivers from his contract to sign with the Los Angeles Clippers, in exchange for a first-round draft pick. A few days later, Ainge made the blockbuster deal with the Brooklyn Nets, swapping Pierce and Garnett for three more first-round draft picks, giving him a total of nine over the next five seasons—more than any other team in the league—and, crucially, even more chips to play with.

Ainge says he would have made the trade a year ago if he could have found a taker, even though his team was still wildly popular, having come within a single game of reaching the NBA Finals. “We didn’t get anywhere close to the amount of picks we ended up getting this summer,” Ainge says. “Those weren’t available. Anywhere. Even one first-round pick.”

Ainge has now brought the Celtics to a franchise-altering crossroads. And today, as he leads basketball’s most storied organization down this uncertain path, he’s come to work dressed in shorts, flip-flops, and a team polo shirt. Even at 54 years of age, Ainge still carries himself with the jockish confidence that defined him during his 14 years playing as one of the premier agitators in the NBA.

During his glory days with the Celtics, he once proudly borrowed a T-shirt from heckling fans in Detroit with the words “I hate Danny Ainge” written across the chest and wore it during warmups. Not much has changed. Last season, hours after he chided Heat star LeBron James for complaining about officials, his Miami counterpart, Pat Riley, said, “Danny Ainge needs to shut the fuck up and manage his own team.” Ainge, who has never appeared to care much what people think of him, doesn’t seem likely to take that advice. “The criticism doesn’t bother me, if it’s informed,” he tells me. “If it’s not informed, then it doesn’t bother me.”

It’s that carefree ease—or, from a less-charitable perspective, arrogance—that forms the popular perception of Ainge as a guy who lives life hitting on 17 while wondering why everyone else is content to stand. But his bravado is balanced with a meticulous, analytical approach, more calculated than impulsive. He may not have a master plan, but he does have a method. And though Ainge is not positive that his method will be able to bring the Celtics another title, he is extremely confident that his method is right.

“I don’t do this job because I have to have it,” Ainge says. “I’m not afraid of making a mistake. I do have a fear of failure that drives me. At the same time, the people I admire in the business are the people who are willing to take some chances. There are no guarantees. You have to be willing to take the shot.”

With the Celtics now on the brink of sweeping change, we’re about to find out just how well earned Ainge’s confidence is. There’s a chance that he will lead the Celtics back to championship glory, just as there’s a possibility that the team will go tumbling down the NBA’s rabbit hole. Confident as ever, Ainge can live with the uncertainty. Whether Celtics fans can is another question.

Growing up in Eugene, Oregon, Ainge was a three-sport star of such magnitude that in 1999 Sports Illustrated named him the greatest athlete in the state’s history. He was drafted out of high school by the Toronto Blue Jays and was playing second and third base in the majors by his 20th birthday. “The NBA didn’t really inspire me as much as Major League Baseball,” he says. “Playing in Yankee Stadium and Fenway Park, those were inspirational places for me.”

Ainge hit just .187 in his third and final big-league season, yet when I asked him if he would have become a successful baseball player, he didn’t hesitate to answer, “I know I would have been.”

But baseball was just his summer job. During the school year, he was earning All-American honors at Brigham Young University on the basketball court, winning numerous player of the year honors during his senior season. When Ainge joined the Celtics in 1981, his new teammates, fresh off winning a championship, couldn’t wait to take the fair-haired golden boy down a peg. As he bricked shot after shot in his first scrimmage, his new coach, Bill Fitch, mockingly said to him, “Not as easy as you thought, is it?” Actually, Ainge was thrilled. “In my mind, I’m thinking, Holy crap, I got any shot I wanted,” he says. “I’m used to facing box-and-ones and double-teams in college.”

But his early years with the Celtics were difficult, as he clashed repeatedly with his hard-ass coach. “He buried me, and I became a whipping boy,” Ainge says. “I had no confidence for the first time in my life. I had no rhythm. My game was a disaster. Peter Vecsey called me Danny Aint, which I thought was really funny and clever. But it was true. I wasn’t a player.”