What It Takes to Preserve the Boston Marathon Memorial

Image via Iron Mountain

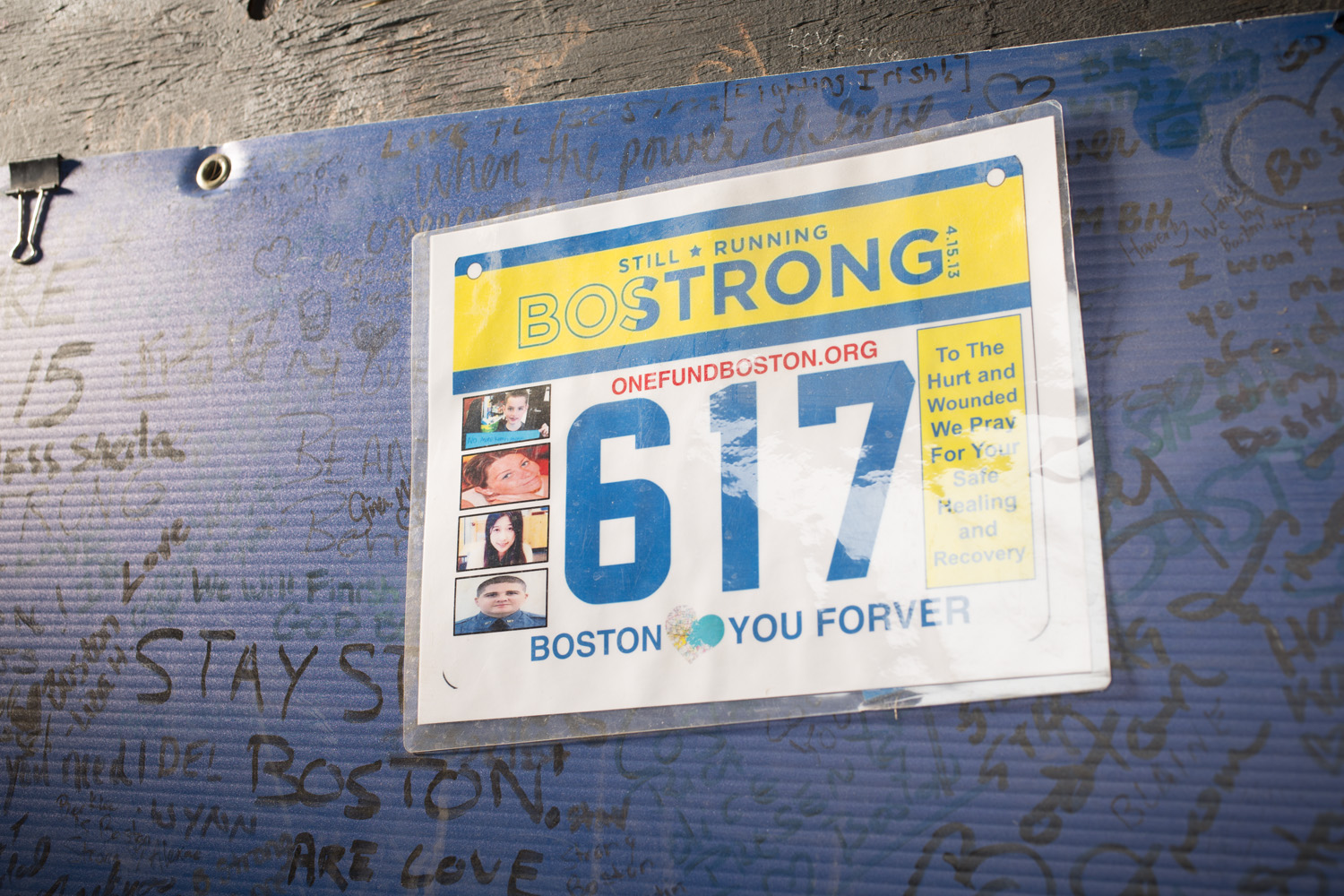

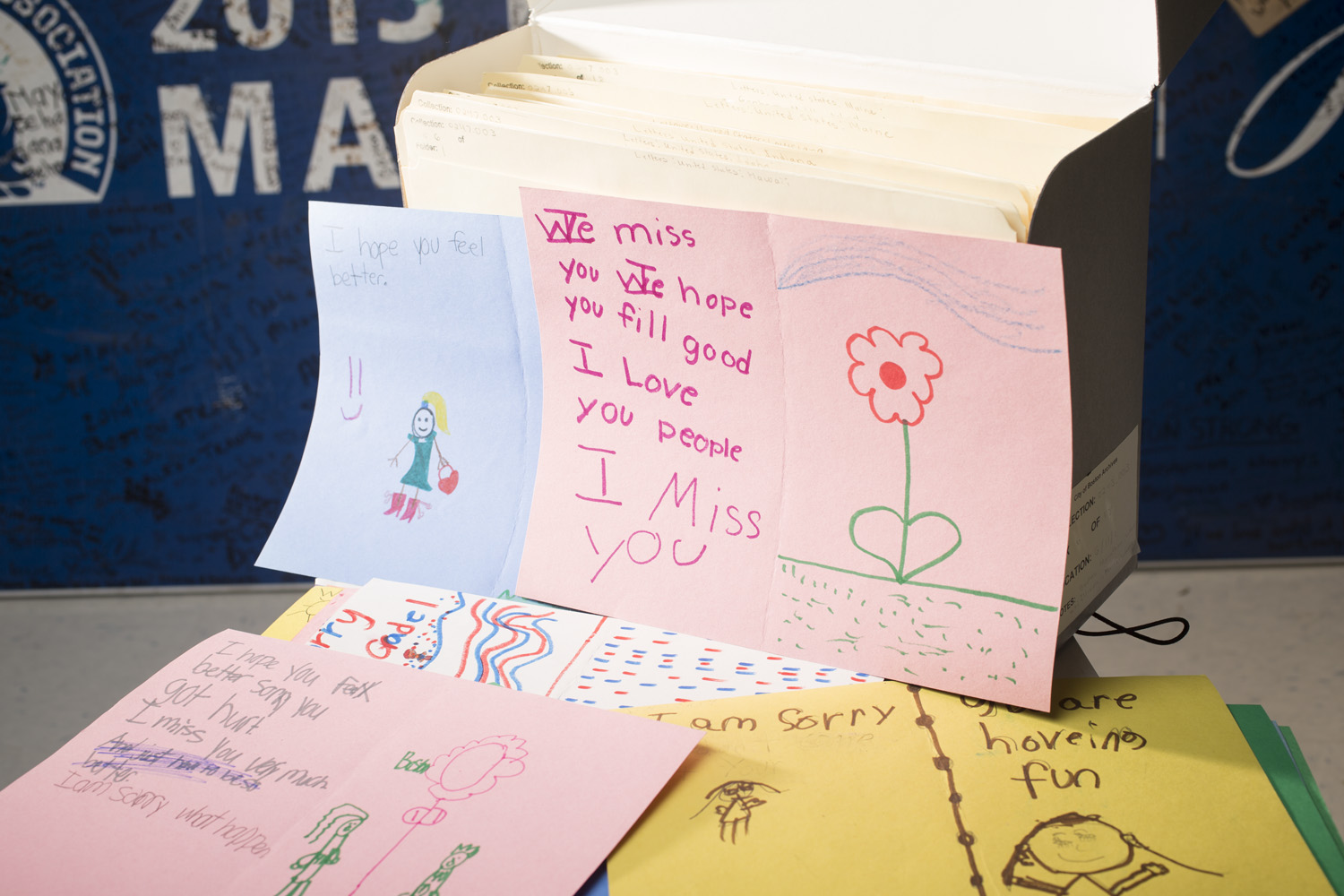

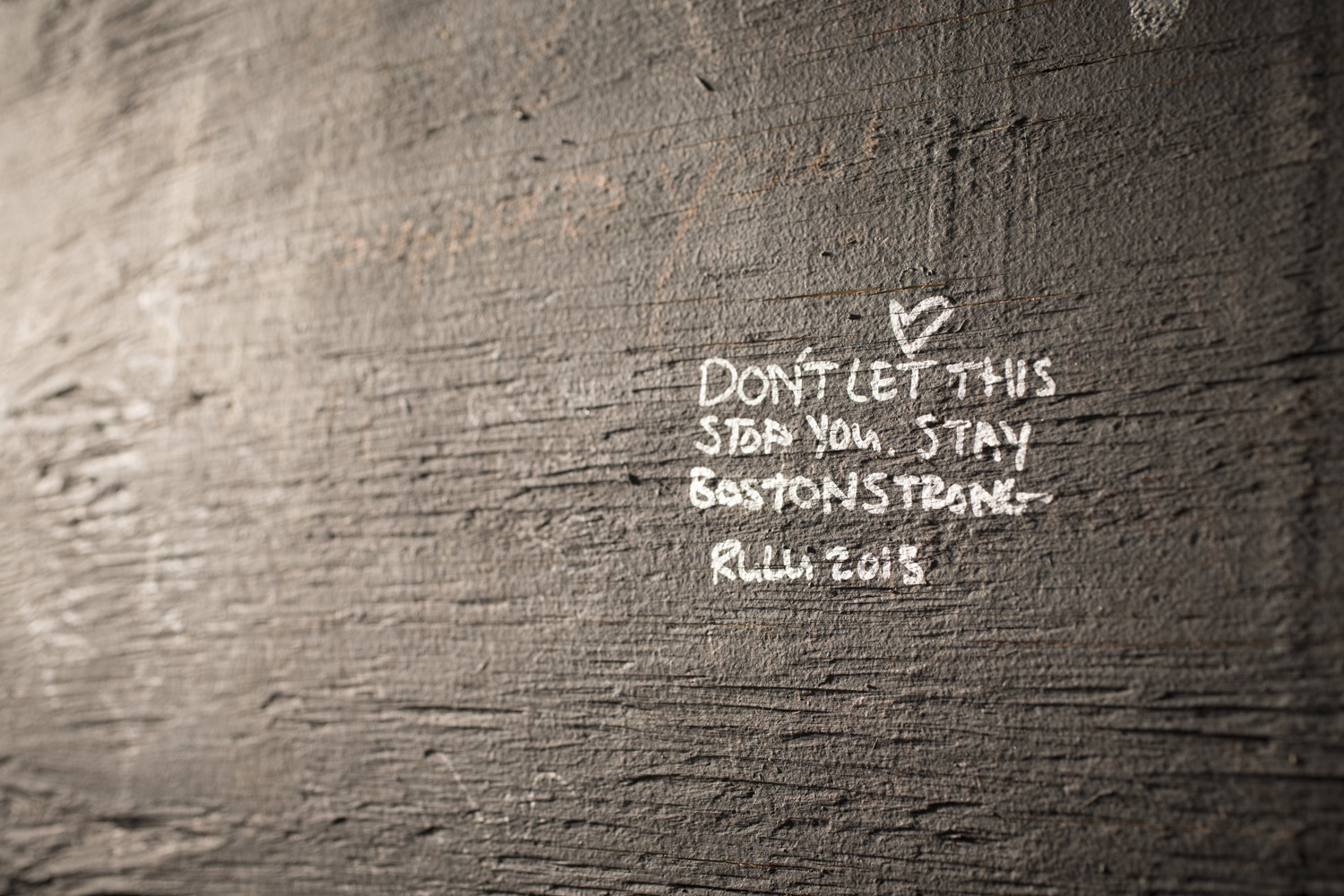

Since January, Nancy Marche has been sorting and sifting through the memorials that were carefully laid down at Copley Square last year for the victims of the Boston Marathon bombings. But even after all of these months looking at the items, she manages to discover new, heartfelt messages tucked away on the sides of the shoes, posters, stuffed animals, and letters that were placed in remembrance near the Boylston Street finish line.

“We cry every day,” said Marche, holding back tears. “And every day you see something different. We’ve been through these boxes a lot, but then you see something that you hadn’t seen before.”

Marche and roughly 10 employees from Iron Mountain, a Boston-based preservation and storage company, have taken on the monumentally emotional task of categorizing all of the items—bears, hats, sneakers, postcards, paper cranes, and thousands of letters—for the last three months, since a majority of the condolences couldn’t be stored in the confines of the City Archives in West Roxbury, and needed a new home.

Marche and workers from Iron Mountain decided to shoulder the responsibility of preserving and sorting all of the tokens of support from the makeshift Copley Square memorial pro bono, after Samantha Joseph, the company’s director of corporate responsibility and sustainability, realized that once the original tribute came down last June, the objects would need to be properly taken care of in order to make them last for what she hopes is a lifetime. “When I visited the site [last year], I took a look at it, and said, ‘somebody is going to be responsible for this, and I’m wondering if that’s something we could help with,’” said Joseph.

Soon after the light bulb went on in her head, Joseph and workers from Iron Mountain connected with City Councilor Stephen Murphy, who was president of the council at the time, and offered their support as a local organization “that cared.” They also offered up financial resources, personal time, and expertise in preserving these types of documents. “Stephen Murphy connected us with the City Archives and we just started working with them right away,” said Joseph.

From there, objects that were temporarily housed inside the City Archives—a space unfitting for larger memorabilia like four-foot-tall Teddy Bears, long whiteboards covered with messages, framed photos, or trophies—were gradually moved from Boston to Iron Mountain’s storage facility in Northborough, about an hour’s drive from Downtown.

The massive building, set back on a long stretch of barren road, offered an expansive, temperature-controlled space for the objects to be housed. It was there that employees like Marche organized each item left behind for the victims into separate categories, before packing them into more than 250 boxes, and carefully sliding them into their own corner of the building, free from the harsh elements and dust. “When some of the things arrived here, they were in big, black trash bags, and we helped organize them by box and by type of item. We tried to help facilitate that process with what we could do here,” said Joseph.

Volunteers spent more than 350 hours on the project, and it didn’t stop at just carefully placing things into designated spots. The sorting included digitizing many of the paper items—letters that flooded then-mayor Tom Menino’s mailbox by the thousands—so they could be included in an online database hosted by Northeastern University. Those smaller pieces of the memorial will be viewable from anywhere in the world, beginning on April 15. “The effort to digitize each letter and card in a way that captured the spirit of it in its physical form was extensive,” said Joseph.

It was also an emotional experience that transcended the typical duties bestowed upon employees at the storage unit. “They took tremendous pride in doing it,” Joseph said. “The City Archives told us, ‘It’s clear that these were scanned with love.’ They noticed how seriously we took capturing their physical feeling.”

On April 7, after working with Rainey Tisdale from the City Archives’ department, items that were slowly plucked from the boxes lining the shelves at the Iron Mountain facility were set up at the Boston Public Library as part of a special tribute display, called “Dear Boston: Messages from the Marathon Memorial.”

Joseph said Tisdale, the exhibit’s curator, meticulously searched through each box to find the best ways to represent the meaning of the Marathon, and outpouring of support showed for the city in the wake of the attack, for the display. “It’s an amazing gift to look at so many items and understand what the message is behind them. She organized those messages into themes,” said Joseph. “There were messages from people who have experienced similar losses, messages for the victims themselves—when you actually looked at everything here, these themes emerged, and she chose items that helped represent that. It’s a beautiful exhibit.”

That display will stay up through May, offering the public a chance to think back to last year’s race by strolling through the temporary memorial, before the objects will again be boxed up and returned to Northborough where Joseph said they will stay “as long as Boston needs us to protect it.”

“Forever,” said Joseph. “We’re honored to have the city ask us to help with this.”

With the emotional one-year anniversary fast approaching and the day of the race just one week later, Joseph said both Iron Mountain employees and the city expect more tokens of remembrance to start showing up in Copley Square. As of right now, there’s no official plan in place as to what will happen with those items, but based on Josephs’ team’s collaboration with the mayor’s office, Iron Mountain will clear a small space on their warehouse shelves for those, too. “Some of it, I’m sure, will end up here,” said Joseph.

Image via Iron Mountain

Image via Iron Mountain

Image via Iron Mountain

Image via Iron Mountain

Image via Iron Mountain

Image via Iron Mountain

Image via Iron Mountain