Big House, Big Mouth

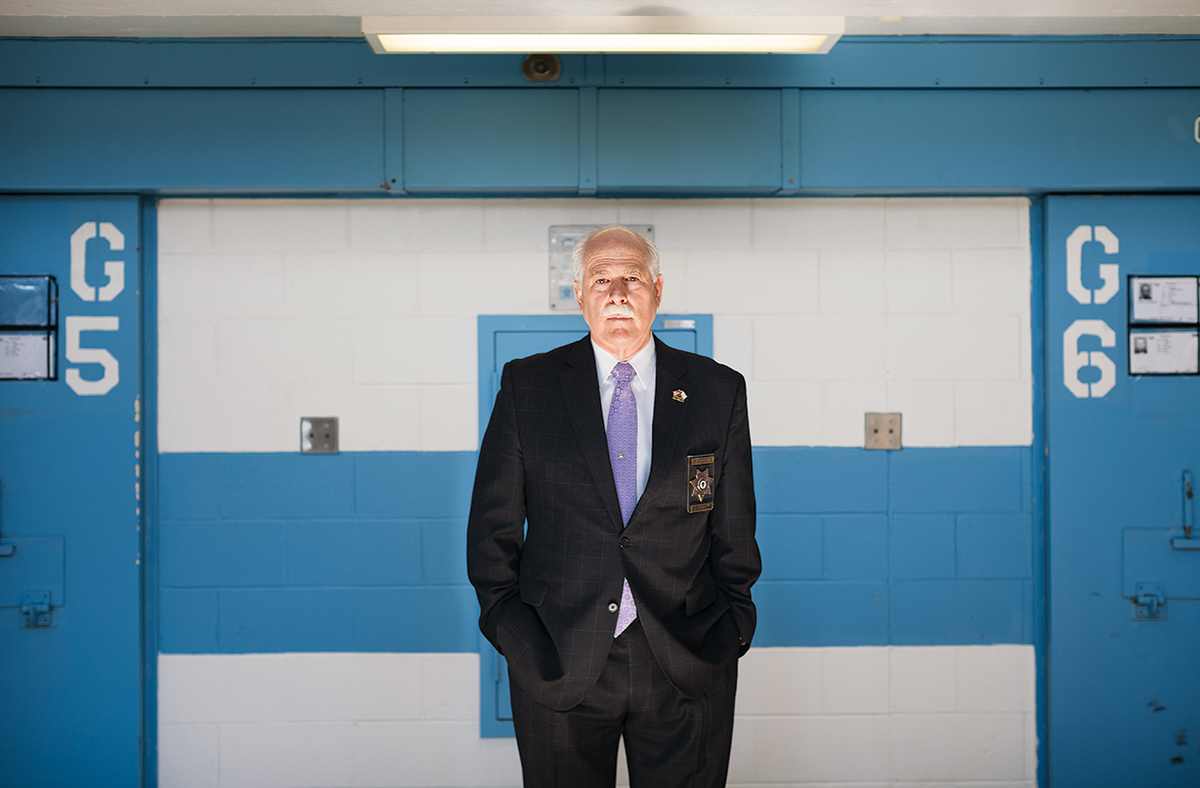

Bristol County Sheriff Thomas Hodgson in his Dartmouth facility. / Photo by Matt Kalinowski

Before Aaron Hernandez ended up in his jail, Bristol County Sheriff Thomas Hodgson was not particularly aware of TMZ. Leaning against the wall of what, until recently, had been the former Patriot’s cell, the 60-year-old sheriff says, “I do know it now.” The celebrity gossip site has all but had Hodgson on speed dial since Hernandez’s arrest in June. It works like this: Some TMZ reporter calls and asks a question like, Can Aaron Hernandez watch Patriots games? Hodgson answers, and then the site cranks out a story, complete with a quote from the sheriff and a big ol’ headline—“AARON HERNANDEZ BLOCKED FROM WATCHING NFL IN JAIL”—that zings all across the Internet. TMZ has also reported that Hernandez did not get cake on his birthday and, in case you were wondering, is not allowed to receive porn (though he has apparently been sent much of the homemade variety).

As sheriff, Hodgson, a Republican who’s been elected to three six-year terms, is charged with running Bristol County’s corrections system. From the moment Hernandez arrived on his doorstep, the sheriff has been eager to tell reporters just how unpleasant his star inmate’s life has suddenly become. Hodgson tells me this is his fourth or fifth time giving a media member a tour of the jail’s high-security “special management unit,” where Hernandez lived for about eight months before being transferred following a February jailhouse brawl. The accommodations in Hernandez’s old 7-by-10-foot cell are indeed spartan: There is a metal-frame bed with a thin mattress, a metal sink connected to a toilet, and a cement desk with a cement stool stuck to the ground. All Hernandez could see out his narrow, barred window was a red fire hydrant and the barbwire fence surrounding the Dartmouth facility. The meals delivered to Hernandez, Hodgson has often repeated, were bland and unsatisfying. The Four Seasons, it ain’t.

Which is exactly Hodgson’s point. Since becoming sheriff in 1997, the former Maryland cop and New Bedford city councilor has made a name for himself as Massachusetts’ toughest jailer—an old-school law-and-order type in the mold of Arizona’s notoriously controversial Sheriff Joe Arpaio. Over the years, Hodgson has instituted inmate “chain gang” work crews, as he calls them, restricted meal portions, introduced medical copays for inmates, and clashed publicly with Governor Deval Patrick. In 2002 he started charging his inmates rent—$5 per day. In protest, prisoners clogged their toilets and hurled feces at their walls, but the fee remained in force until 2004, when a judge overruled it. All of these gambits have earned Hodgson his share of headlines and media appearances, but now, with Hernandez under his care, he has more opportunity than ever to make his views heard. Since last summer, he’s been on ESPN SportsCenter, WEEI, and Fox 25, and has been quoted in articles all over the country. After Hernandez’s fight, Hodgson says, he spent a day and a half on the phone talking with the press.

The sheriff, who’s up for reelection in 2016, says he’s working to get a message out to kids about consequences and making good choices. But when Hodgson goes on camera or talks to a reporter, is he doing it to educate the kids—or to advance his career?

Hodgson’s office, in a cinderblock building beside the Dartmouth jail, is a treasure-trove of knickknacks and memorabilia. In a trophy room off to the side, a shelf features two shots of him with George H. W. Bush, set up next to a portrait of Ronald Reagan. Across from his desk, there’s a bust of Abraham Lincoln with a framed copy of the Gettysburg Address on the wall above it. Nearby hangs a fanciful painting of past Republican presidents sitting around a poker table. It’s like that famous print of card-playing dogs, except with Richard Nixon.

In Massachusetts, the most serious convicted criminals are sent to state prison, but those awaiting trial, like Hernandez, and prisoners who are sentenced to two and a half years or less, enter one of the state’s 14 county corrections systems. Elected sheriffs essentially run these as their own private fiefdoms. Of the roughly 1,000 inmates under Hodgson’s care, about half are pretrial and the rest are low-level convicts.

From the moment he took office, Hodgson, who sports a white lawman’s mustache, has never been shy about accentuating the differences between him and most Massachusetts politicians—or about courting controversy. One of his first acts was to eliminate televisions, weight-lifting equipment, and smoking from his jails. He’s also made a show of cutting coffee and orange juice from the budget (the OJ, at least, was replaced by Tang). A judge once even chided him for not giving inmates adequate access to bathrooms. Hodgson has always argued that jails should run as leanly as possible—that it’s better to allocate resources elsewhere—and they should be unpleasant places to which you’d never want to return. In 1998 prisoners became so fed up with the conditions at Bristol County’s nearly 200-year-old Ash Street Jail that they rioted. Soon after, a group of inmates sued. Despite their accusations, Hodgson declared the facility “perfectly fine.” (That was not Hodgson’s last riot. In 2001, during an uprising at the Dartmouth facility, a guard was taken hostage for more than 30 minutes. Again, living conditions were cited as the cause, though Hodgson contests that allegation.)

Hodgson’s biggest public controversy came in 1999, when he instituted inmate “chain gangs.” Across Massachusetts, sentenced inmates are released for supervised work in the community—whether it’s picking up trash or painting or something else—but Hodgson forced his prisoners to wear shackles while doing it. He’s argued that the program is voluntary and that the inmates are happy to be able to get out of the prison to do work (and that he also has work programs for lower-risk inmates that don’t require restraints). But many have found the practice, at best, unnecessary and, at worst, offensive and demeaning. When Hodgson introduced the program, the media erupted in outrage, with even the conservative Herald editorializing against the chains. Despite the uproar, Hodgson’s “chain gangs” continue today.

Over the past eight years, Hodgson has also been a frequent thorn in Governor Patrick’s side, opposing him on just about any issue anyone asks him about. The biggest dustup came in 2011, after Patrick declared his opposition to a Department of Homeland Security program called Secure Communities, which allows the feds access to local and state databases that can be used to check someone’s immigration status. Hodgson, who operates a detention center in Dartmouth that the federal government pays to hold undocumented immigrants, supported the program. Even as Patrick fought to keep Secure Communities out of Massachusetts, Hodgson was working to implement it anyway. “With the governor, look, philosophically he and I differ,” the sheriff says. “He didn’t like the statement I made that said his decision to say that Secure Communities was bad for Massachusetts was moronic.” After Patrick later vetoed millions in funding earmarked for Hodgson, the sheriff hit back hard, helping persuade the legislature to override Patrick’s cuts.

Hodgson believes that growing up in Maryland with 12 siblings taught him the importance of being a good communicator—and of finding ways to make his voice heard. He says he’s always viewed controversy and media attention as a means to an end. “If it’s controversial, that’s not a bad thing, because it raises the debate with the public,” he says. “And it makes the public think.” If the ensuing debate moves policy in the direction he wants it to go, all the better.

Not surprisingly, Hodgson has attracted many critics. Leslie Walker, the executive director of Prisoners’ Legal Services of Massachusetts, says that when she started seeing him on TV after Hernandez’s arrest, “I found it not unpredictable. I found it amusing, more than unseemly. He’s a politician. He wants to get reelected.”

State Senator Brian Joyce, a Democrat who represents parts of Bristol County, which includes crime-heavy areas like New Bedford and Fall River, has a similar view. “I see him somewhat as a showman,” Joyce says. “He’s good with a quip. He’s good with a publicity stunt.” A common estimate is that 90 percent of convicts in the Massachusetts county system are dealing with some form of addiction, and Joyce points out that many also suffer from mental-health issues or have never received any meaningful education or job training. “An enlightened sheriff today,” he says, “needs to be more than just lock ’em up and throw away the key.”

While Hodgson favors a scared-straight approach, other sheriffs in Massachusetts, both Democrat and Republican, focus their rhetoric and efforts more on rehabilitation, and on providing the counseling and education inmates need to successfully rejoin society. “I spend a lot of energy on reentry and programming,” says Essex County Sheriff Frank Cousins, a Republican. At any given time, Cousins says, he has 285 to 325 inmates living in a monitored prerelease center outside of the prison. Currently, 75 of them have jobs in the community. “I’m a pretty conservative guy,” he says, before adding that he thinks the programming, designed to reduce recidivism, is the type of good policy that also makes good business sense.

Sheriff Michael Bellotti, a Democrat from Norfolk County, has a similar approach. The reasoning, he says, is simple: His prisoners are headed back to the community sooner than later. The maximum county sentence is two and a half years, but Bellotti estimates that the average stay is eight or nine months. “Things like education, lack of healthcare, mental- health issues, vocational skills, lack of housing, and substance abuse, we attack all those areas,” Bellotti says. “We assess and then we come up with a plan for programming.”

While Hodgson offers programming such as drug counseling, vocational training, and religious mentoring, defense lawyers and inmate advocates frequently complain that there’s not enough of it. And that, too often, the programs that do exist don’t have enough spaces, helping make Hodgson’s prison among the most dreaded in the state. According to defense attorney Michele Rioux, when a judge was recently weighing whether to sentence one of her clients to Hodgson’s prison or to a longer stint in the Massachusetts system, the client requested the longer sentence.

A mountain of other complaints against Hodgson has piled up over the years: Critics questioned his purchase of a $500,000 “mobile command unit” in 2001. In 2010, the Globe ran a story reporting that a curious number of Hodgson’s employees had been given inflated job titles, making them eligible for larger pension benefits. During Hodgson’s last reelection campaign, his opponent, John Quinn, blistered him with patronage attacks, noting that Hodgson was running up big legal bills for the county by pursuing an unusually high number of lawsuits, and that many of the billable hours seemed to be going to firms run by his campaign supporters.

Hodgson brushes aside the criticisms. He says his philosophy is all about accountability. “While you’re here, it’s not about entertainment,” he says. “It’s about focusing on making yourself a better person. I’m for programs for people who want to help themselves. But people aren’t being honest about the prison system.” He argues that inmates aren’t under his care long enough for most programs to have any real effect, and that he’d rather see public money spent on reaching school-aged kids to try to break the cycle at the beginning. “We’re never going to stop building prisons and [start] cutting into the recidivism rate in this country until we start changing our policies in dealing with kids in third and fourth grade,” he says.

As of right now, it’s impossible to tell whether Hodgson’s tough-on-crime approach works. According to Natasha Frost, a professor and associate dean at Northeastern University’s School of Criminology and Criminal Justice, there is a general sense in national research that the more progressive approach favored by Cousins and Bellotti is better at reducing recidivism, but the data is not stone-cold conclusive. Within Massachusetts, even though the state allocated more than half a billion dollars this year to run its county prisons, remarkably, nobody is measuring the 14 different systems’ effectiveness. Consistent recidivism numbers simply aren’t tracked across the different counties (though an effort to fix that is under way). When I asked Hodgson’s press person whether Bristol County keeps any sort of internal recidivism statistics, I was told it does not.

Regardless, Hodgson remains popular with the people who matter most: Bristol County voters. The county is fairly politically balanced—it contains both a healthy chunk of old Scott Brown country and Democratic strongholds like New Bedford and Fall River—and in his last election, in 2010, the sheriff racked up 72,581 votes, compared with his Democratic rival’s 60,251. He is constantly rumored as a GOP candidate for higher office, including Congress, but says he intends on running for another term as sheriff when he’s up again in 2016. “You never say never, but I can tell you honestly that I really enjoy this job,” he says. If nothing else, after his nearly two decades in office, Bristol County voters know what Hodgson is about. “Look, I believe in what I believe,” he says.“I’m not shy about telling people that.”

Hodgson says that Hernandez is treated like any other prisoner, but in reality that doesn’t always happen. When Hernandez arrived, standard procedure was for Hodgson’s staff to examine Hernandez’s tattoos to determine if he had any gang affiliations. Normally Hodgson does not get involved, but this time, he says, “I personally interviewed him myself after my gang guys did just to be sure.” (There were no gang affiliations found.) Typically, someone lower-profile than the former Patriot—who is charged with first-degree murder—would be kept among the general population, but Hodgson says Hernandez was placed in the high-security unit to protect him from potential attacks. There, he was allowed out of his cell for three hours a day: one hour in the morning to shower and make calls, one hour midday to walk around a small courtyard outside his unit, and, in the afternoon, one hour for outdoor recreation inside a 12-by-8-foot chainlink pen. No other prisoners were allowed near him unless they were restrained, so when Hernandez started a fistfight in late February, Hodgson was surprised. He and his staff were so focused on safeguarding Hernandez, he says, “We didn’t anticipate that the person we were protecting would turn around and try to harm the people we were protecting him from.”

Hodgson is pursuing an assault and battery charge against Hernandez, so he told me he couldn’t divulge any details about the incident. However, he made it clear that Hernandez was walking around the courtyard during one of his hours outside his cell when he attacked another inmate who was in restraints while being transferred to another part of the prison. “It was relatively quick, because we had three officers right in the immediate vicinity,” Hodgson says. “There was no medical requirement or anything like that.” Hernandez has since been moved to a “higher-class” unit—it’s similar to the one Hodgson showed me, except now he’s allowed out of his cell only one hour per day.

Hodgson says he’s made an effort to be a fatherly influence for Hernandez, whom he talks with every couple of weeks. With the exception of the alleged assault, “he’s been pretty quiet, laid-back. Reads books,” Hodgson says. The sheriff suggested he pick up Mitch Albom’s Tuesdays with Morrie, and says that after reading it, Hernandez recommended it to the rest of his family. Hodgson also asked him if he read the Bible, which Hernandez has been doing as well. Says Hodgson, “I told him in the beginning, ‘Ask for help.’”

Hodgson places great faith in the power of religious healing. He recalls telling Hernandez, “Always remember that God writes straight with crooked lines. What that means is that when you’re reading Tuesdays with Morrie, it might be a week, it might be a month later—something’s going to click for you, or somebody’s going to say something, or an experience will happen that you don’t know where it came from but it somehow altered your mood, your attitude, your perspective on life. You won’t be able to understand where it came from, it just happened. So we talk about that kind of thing.”

In a way, herein lies the rub with Hodgson: While others are less confident in the combined healing powers of Mitch Albom and the Bible—opting instead for more counseling and rehabilitation programming—Hodgson is of the “salvation lies within” school. And just as he saw the chain gang and $5-per-day controversies as chances to advance his argument to the public, so he sees Aaron Hernandez’s stay in his jail as another opportunity.

“He’s a great football standout [who’s now] sitting in a 70-square-foot cell with no car, with a very different kind of uniform, and being told what he can eat and when he can eat and having his freedoms restricted,” Hodgson says. “This was a huge lesson that the press were actually helping to promote out there for kids.”

Hodgson recalls a reporter once asking him if he’d rather have Whitey Bulger or Hernandez staying in his jail. “No children relate to Whitey Bulger, but they do to Aaron Hernandez,” he says. And so the answer was easy: “Aaron Hernandez all day long.”