Mayor Marty Walsh Is Cleaning House

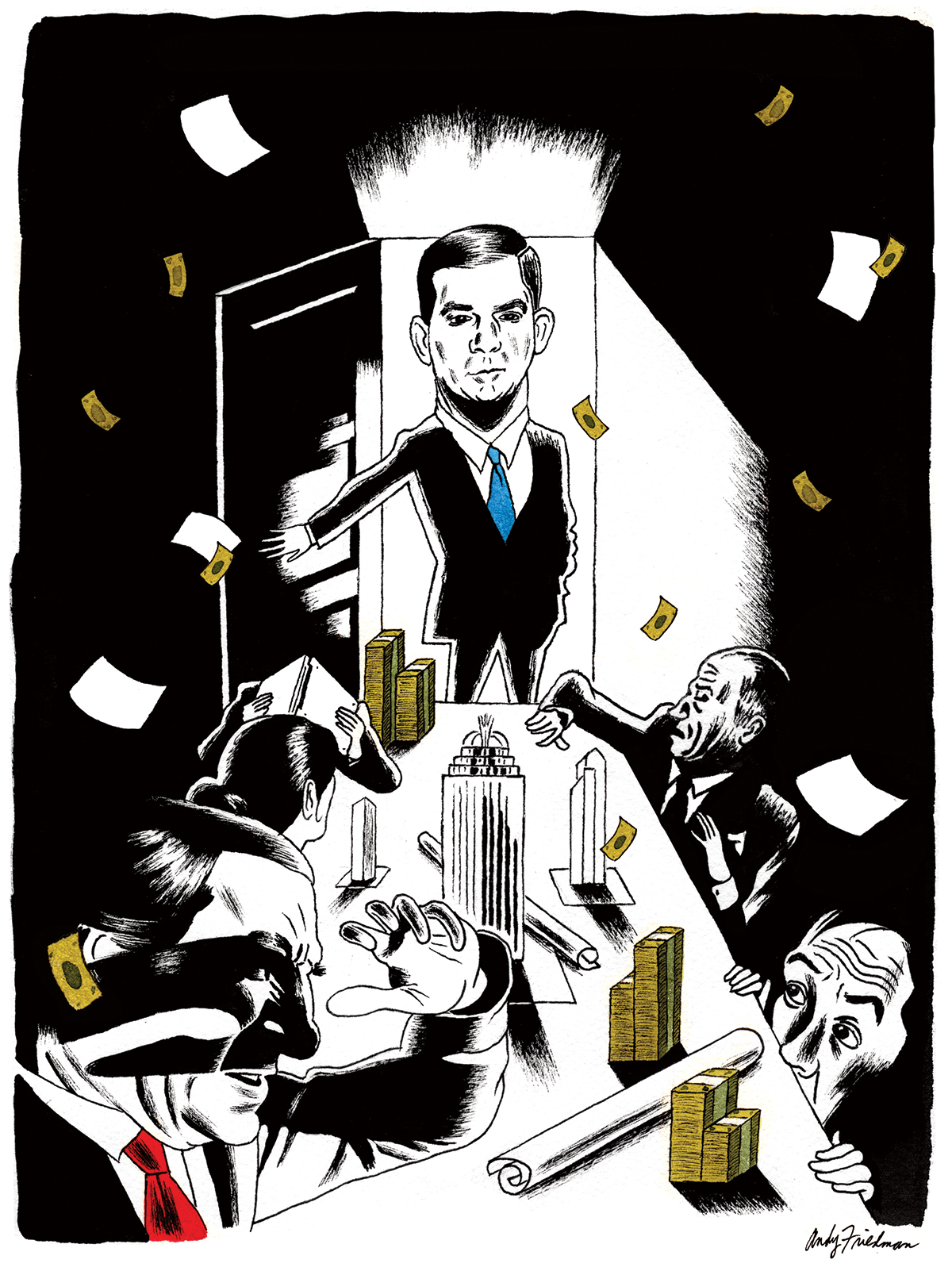

Illustration by Andy Friedman

Six months into his tenure at City Hall, Mayor Marty Walsh appears to be proceeding cautiously. He’s launched no grand public crusades and made few big announcements. But appearances can be deceiving. When I went to see Walsh recently in his fifth-floor office, he made it clear that the City Hall he inherited is broken, and he intends to fix it. Not next term, not next year—now. He’s been reluctant so far to criticize his predecessor, whose 20-year reign continues to cast a deep shadow across the city, so what he wouldn’t say—not publicly—is the name Tom Menino. But read between the lines and it’s clear he believes that, for all the progress the city has made, Menino’s Boston was too often run by fiat, at the mayor’s personal whims. When Walsh took office, he quickly came to believe that after two decades of Menino’s iron rule, several of the city’s most important agencies were rotting from within.

The new mayor may not be intentionally gunning for Menino, but he isn’t shying away, either. Walsh has already quietly launched the first major offensive—perhaps the defining offensive—of his tenure. Its opening salvo is a far-reaching independent audit of the city’s most notoriously difficult—and crucial—agency: the Boston Redevelopment Authority. Walsh aides believe the BRA scrub, a months-long audit by the global firm KPMG, is the first-ever serious, outside look at the condition of the agency.

People close to the Walsh administration say KPMG’s report will describe an agency wracked by poor management, worse morale, weak financial oversight, and archaic record-keeping. More important, it will likely aim squarely at the source of the BRA’s might: the fact that the agency has always been allowed to make up and play by its own rules, without ever telling anyone else what those rules are.

The stakes for the city couldn’t be higher. The BRA controls planning and real estate development in Boston, and nothing gets built here without its say-so. Over his two decades in office, Menino used it to maximize his grip on the biggest decisions in the city. The BRA’s sweeping powers allowed him to leave his fingerprints all over the Seaport, as he essentially conjured its new “Innovation District” from thin air. And because the BRA’s powers are so vast, whoever controls it has every developer in Boston at his mercy. Menino knew this better than anyone, and used the agency for everything from shaping big plans to micromanaging tiny details. It’s why the gleaming blue tower at 111 Huntington Avenue, beside the Prudential Center, has an ornate, crownlike structure sitting on its roof. Menino was fine with tall buildings, but he hated flat rooftops. So the building’s architects, who desperately needed Menino’s assent, lined up a dozen potential treatments for the roof, and granted the final decision on one of the city’s signature skyline elements to Hizzoner. Menino, as befits a king, chose the crown.

Sitting in his office on a dark leather couch, right next to James Michael Curley’s old desk—the one he brought in to replace Menino’s—Walsh paints a different picture of how he’d like to run the BRA. “If somebody shows me a design of a building, and if the neighborhood’s happy with the design, then I’m happy with the design,” Walsh says. “I’m not going to say, ‘It should be this.’ It’s not my style.” It’s also a clear shot at the bureaucratic culture Walsh inherited from Menino.

When it’s released, Walsh’s BRA audit is likely to be a bombshell. He didn’t wait for the results to fire 14 BRA employees—he did that in the spring. But that appears to be just the beginning: Administration insiders expect more heads to roll soon. And the BRA isn’t alone in getting a tough look. The city’s Inspectional Services Department has also been audited, and the conclusions are expected to be equally critical. More audits are imminent, but perhaps more important than the result of any individual report is the signal Walsh is sending about how he intends to govern the city. The message is clear: We’re seeing the undoing of Tom Menino’s Boston—and the making of Marty Walsh’s.

Brian Golden is the acting director of the BRA, which is interesting, because Brian Golden does not much care for how the BRA has been run. As we chat in his City Hall office, Boston’s BRA-built skyline spreads out behind him. Office towers—built on land the BRA helped bulldoze, with zoning the BRA wrote—march in a line, from Government Center below, down State and Congress streets, to the harbor. For years, the bureaucrats running the agency have believed that the BRA’s greatest strength was its freedom—its ability to do what it wanted, when it wanted, and rarely have to apologize for it. Golden waves at the landscape the agency created, and then tells me the BRA needs to be torn down from the inside and rebuilt.

“I think a big piece of what we’re trying to accomplish,” Golden says, “is improved processes and increased transparency, to eliminate the perception that everything [at the BRA] is arbitrary and capricious. And hopefully, eventually, demonstrate that this place is an agency with a soul.”

This may not sound historic, but at an agency that has been notoriously capricious, it is. The city of Boston and the state legislature created the Boston Redevelopment Authority in 1957. The city was an economic backwater, and Bostonians were fleeing it for the suburbs. Between 1950 and 1960, Boston lost more than 104,000 residents. Rooming houses filled the Back Bay, and ramshackle, half-rotted shacks crowded the waterfront. The Custom House Tower, which had opened in 1915, was the city’s tallest building. Officials feared Boston was hollowing out, and becoming a city of slums. They felt the need to give Boston a jolt, and the jolt they gave it was the BRA.

The agency folded several disparate roles—economic development, planning, and real estate permitting—into one hugely powerful entity. In its early years, the BRA wielded eminent-domain powers freely, seizing and bulldozing the West End, Scollay Square, and parts of Roxbury in an aggressive urban-renewal campaign. The neighborhood Golden grew up in, Allston, rose up in open rebellion against a BRA-led urban-renewal effort during the 1960s.

Past mayors John Hynes and John Collins built Government Center and the Prudential Center through the BRA. Kevin White used it to build the Hancock tower, and much of the Financial District. Even as the federal urban-renewal funds that paid for the BRA’s initial demolition spree withered away several decades ago, the agency has endured, because it’s Boston’s most formidable vessel for mayoral power. Most other major cities separate their planning and real estate permitting agencies; the BRA does both, and runs point on economic development, and shapes the zoning that enables new buildings to be built, and possesses eminent-domain powers to boot.

Since the agency is run by a board of five appointees, four selected by the mayor, it, in effect, operates at the mayor’s pleasure. Developers in Boston can’t build anything of consequence without going through the BRA first, giving the mayor powerful influence over them. The agency is largely immune from outside political or public pressure. It exists off the city’s books—it owns its own land, collects its own revenues, and controls its own budget. And because this massively powerful agency doesn’t answer to the city council, the BRA gives the mayor the power to make or break developers, and neighborhoods. The only person actually capable of checking the agency is the mayor, who typically has little incentive to do so. And so, for good or ill, when the BRA—and the mayor—want to move the needle on a development project, the needle moves more quickly.

Tom Menino’s BRA opened new development frontiers and remade broad swaths of Boston. Menino also used the BRA to tinker with civic architecture, to take care of developer friends, and to freeze out political enemies. Menino’s BRA was a black box that exercised its powers unevenly, and unpredictably. It ushered in new developments in the Seaport, at North Station, along the Greenway and the Fenway, and in Downtown Crossing. But it also jammed up numerous developers in those same neighborhoods who were pushing projects similar to those that sailed through the BRA.

Most famously, Menino all but banished Don Chiofaro, the brash developer proposing a new harborside tower, to Siberia for refusing to shut his mouth and kiss Menino’s ring (Chiofaro’s project never got built, either). But the real faces of Menino’s mercurial BRA were developers like John Rosenthal, who couldn’t get a call back when the BRA was handing out tax breaks like Halloween candy; and Equity Residential, which has been stuck trying to redevelop a dumpy West End garage for four years, even as taller buildings queue up around it; and Skanska, which received a public dope slap for trying to build a Fenway apartment tower as tall as its better-connected neighbors. For the past two decades, the worst place for a developer in Boston to be has been Menino’s doghouse.

In Menino’s final years, the BRA was a cautious, reactive, hyper-political agency that had grown as unpopular among developers as it was among Boston residents. A Suffolk University poll had Menino leaving office with an 81 percent approval rating; that same poll had only 26 percent of Bostonians viewing the BRA favorably. There seemed to be few rules or standards outlining what developers had to do to get, or lose, coveted building permits. A small group of developers—favored by Menino—prospered, while others complained that the BRA operated like a banana republic. But in truth, even those who made it through the BRA in one piece couldn’t explain how they’d done it.

The single worst performance Walsh turned in as a mayoral candidate came last October, when he called a press conference to roll out a sprawling, only-somewhat-coherent plan for overhauling the BRA. Walsh stood on City Hall Plaza that day, fighting the glare off an iPad screen, stumbling through talking points that he appeared to be reading for the first time. He looked overmatched—by the setting, by the details of the plan in front of him, by the sheer scope of the reforms he said he wanted to pull off. He raced through the fumbling performance and walked off as quickly as he could.

Since he took office, members of Boston’s development community have been grumbling that they don’t know what Walsh is doing with the BRA. They don’t know where the agency is heading, who’s in charge of the thing, what the new mayor’s vision is, or who they can cut development deals with. Walsh isn’t comfortable with big speeches or sweeping pronouncements. It’s part of his blue-collar charm, but it could eventually hurt him if voters and constituents feel they’re being kept in the dark. As he sets about cleaning up City Hall, Walsh sometimes goes about the job with all the flair of a guy picking up some shirts at the dry cleaner.

“I think of Marty as someone who’s very thoughtful, who listens very well, not someone who needs to inject himself, or his personality, into the center stage,” says Mark Erlich, the executive secretary-treasurer of the New England Carpenters Union and a longtime Walsh backer. “Because he’s comfortable in his own skin, it makes a difference in how he moves. He’s not always looking for a dramatic headline.”

Marty Walsh rose from the legislative back bench to the mayor’s office because he’s a dogged worker who’s extremely skilled at retail-level politics. He would rather take questions than deliver a speech. He’d rather work a small room than a large one. He’s at his best when he’s just being Marty from Savin Hill. He’s not going to jump into the Charles River for attention like Bill Weld, or try to outdo his predecessor with sweeping policy pronouncements like Bill de Blasio. As mayor, Walsh is staying where he’s comfortable. He’s pressing the flesh in Boston’s neighborhoods and working the inside game, banging away at policy out of public view. He’s firm on where he wants to go, but he’s willing to play a long game, and give his staff running room.

“I talk to Brian Golden probably once a week; I see him a couple times in the hallway,” Walsh says. “I have complete confidence in him. I’m not a day by day, wanting to know every single move they’re making. I want to be there to close the deal, or when there’s a problem.”

Walsh’s administration has been quietly hammering away at the BRA for months. They don’t have much to show for the effort publicly because the turnaround energy has been spent internally. Mounds of complaints collected over the course of last fall’s campaign convinced Walsh that he needed to scrub the BRA’s management and finances before he tried to radically reshape the agency. That led to the KPMG audit, which he launched in February.

Walsh is moving against the BRA partly out of political necessity. The BRA that greeted Marty Walsh in January was as dysfunctional as it was powerful. And if he doesn’t fix that dysfunction, sooner or later, he’ll have to own it.

And the BRA isn’t alone. Walsh wants to give the audit treatment to every agency he oversees. The deeper the new administration digs, the longer the to-do list grows. For instance, a shocking amount of city business still happens on paper, not on computers. Basic records on everything from staff diversity to logs of vacation and sick time are virtually nonexistent. The city’s Inspectional Services Department, which processes building, housing, health, construction, and restaurant permits, is as much of a basket case as the BRA is. The consulting firm McKinsey & Company, which audited ISD for Walsh, describes it as a complex, antiquated agency that takes months to issue permits for simple jobs like replacing a deck, and that it does so with a scowl.

Today Golden, the BRA’s interim director, says that few of the agency’s problems came as a surprise to him. That’s because he’s been working there since 2009, and he says its shortcomings have bothered him for years. “Everybody [inside the BRA] has a beef about what we do wrong,” Golden says. “There’s no one here who thinks everything is fine. Most have a fairly healthy catalog of grievances.” He says that the BRA’s reputation outside City Hall is often as “a dark, brooding force perched at the top of City Hall, that swoops into a neighborhood and wreaks havoc every once in a while.” He also does not push back particularly hard against that impression.

Golden is certainly an unlikely figure to upend the BRA. He was a Menino appointee who filled the agency’s top job when Peter Meade left the director’s office in January. Walsh had no say in Golden’s ascension, and could replace him at any time. But instead of rushing to stuff his own hire atop the BRA, Walsh has given Golden—who’s also an old friend from the State House—a free hand to fix everything that’s ever bothered him about the agency.

The pending audit has the potential to get very ugly for Menino and his allies inside the BRA. But Golden has been treating it as a friendly exercise—almost like a chance to fill out the damage report on a rental car before you leave the lot. Here, after all, is an opportunity to catalog everything that’s wrong with the BRA, and maybe actually fix it once and for all.

“This place works too much with folklore,” he says. “I can’t tell you the number of times when I said, ‘Well, can I see the policy? Can I see the protocol that governs that?’ Well, we have a very clear protocol, but it’s not written, but this is the way we do it. It’s folklore. It has always gnawed at me…. I’ve been uncomfortable with the notion of that kind of power that is not tethered to some kind of objectively clear guidance. We’re going to spend a lot of time fixing that.”

The agenda Golden is pushing now is grunt work. It’s largely invisible to anyone outside City Hall. But it’s also extraordinarily ambitious. Per Walsh’s orders, he’s transforming an agency built on secrecy into one that’s both transparent and predictable—a process that means wiping out a bureaucratic culture that revolved around fixers and personality politics.

“I think there was a feeling here that, to write things down, to create policies that set parameters and govern decision-making inherently limits decision-making,” Golden says. “And this place didn’t like limits on its decision-making.” Like it or not, those are exactly the kinds of restrictions that are now being baked into BRA policy: Golden is creating firm limits on the BRA’s decision-making, and committing the agency to live within its new limits. In other words, he’s trying to turn an agency that’s been run by the rule of one man into one that’s governed by the rule of law.

Marty Walsh has a fundamentally different relationship with political power than Menino enjoyed. Walsh recognizes that he doesn’t need the limitless power the BRA has offered, because Boston is no longer a city that’s going to grow by fiat. Boston doesn’t need a BRA from 1957 anymore. It doesn’t even need the one from 1993, the year Menino took office. There’s no room left in the city to wholesale build new neighborhoods, like Menino did with the Seaport. And Boston’s biggest challenge is no longer that people are fleeing the city—it’s that they’re flooding it. Walsh’s success won’t just be measured by how many new shiny buildings he puts up—it’ll instead be measured by what he does to prevent the working and middle classes from being priced out of the city. Now more than ever, Boston needs an agency to manage growth. To do that, Walsh doesn’t need raw power, but the political legitimacy that comes from taming the BRA and earning buy-in from the city’s neighborhoods.

Walsh’s decision in March to fire 14 BRA employees—the agency’s entire economic development staff—generated more attention than anything else the new administration has done with the BRA. The attention missed the point of the firings, though. Walsh wasn’t putting blood on the floor as a show of strength, or clearing room to muscle his own people in later. The firings signal a change in hierarchy inside City Hall. At the same time that Walsh is curbing the BRA—establishing new boundaries the agency has to live within—he’s also knocking it a few rungs down the ladder.“The BRA is one component of economic development in the city, but so is small business, so is neighborhood development, so is Main streets,” Walsh says. “Tourism is part of economic development. There was nothing that ties them all together.”

The something that now ties them all together is John Barros, the former community-development leader and mayoral candidate who now serves as Walsh’s chief of economic development. Barros doesn’t have any legal sway over the BRA, but he and Walsh are setting up a new dynamic under which the BRA’s work will involve executing a road map that Walsh and Barros hand to it.

Economic development, Barros argues, is “clearly bigger than the BRA. We’re going to have a broader scope than real estate development could offer.” Barros says City Hall will launch a series of intensive neighborhood master-planning efforts, which will serve as the blueprints for new development. The plans will share some baseline goals, like growing dense, moderately priced homes and neighborhood centers around transit hubs. But residents, Barros says, will be empowered to help chart their own future. The BRA will get to work only afterward, when the agency will work with developers to execute the neighborhood plans.

Of course, Walsh’s BRA overhaul could go upside down in any number of ways. It could incite a turf war between the agency and Barros’s office. It could empower the loud, highly organized anti-development activists who have nipped at the BRA’s heels for years. During the campaign to replace him, Menino worried aloud that any talk of overhauling the BRA could chase developers out of town. Walsh is taking the risk anyway, because more than any other mayor, his vision depends on reforming the city’s relationship with the BRA, and with development in general.

As real estate prices in the city rocket into the stratosphere, Walsh’s goal of preserving Boston for the working and middle class without getting in the way of its current economic boom is an exceptionally tricky one. And if he has any prayer of pulling it off, he first has to change Bostonians’ perception of the BRA. Narrowing the BRA’s powers and scaling back its scope are means to an end—a healthy development environment.

“It’s making sure people’s voices are not only at the table, but valued,” Barros says. “I don’t think Boston residents are as scared of development as they are scared of development they haven’t been a part of helping to shape. How can we stop the really dysfunctional relationship between development and residents?”

Even if he hasn’t announced them too loudly, Marty Walsh has a few ideas.