The Deval Patrick Problem

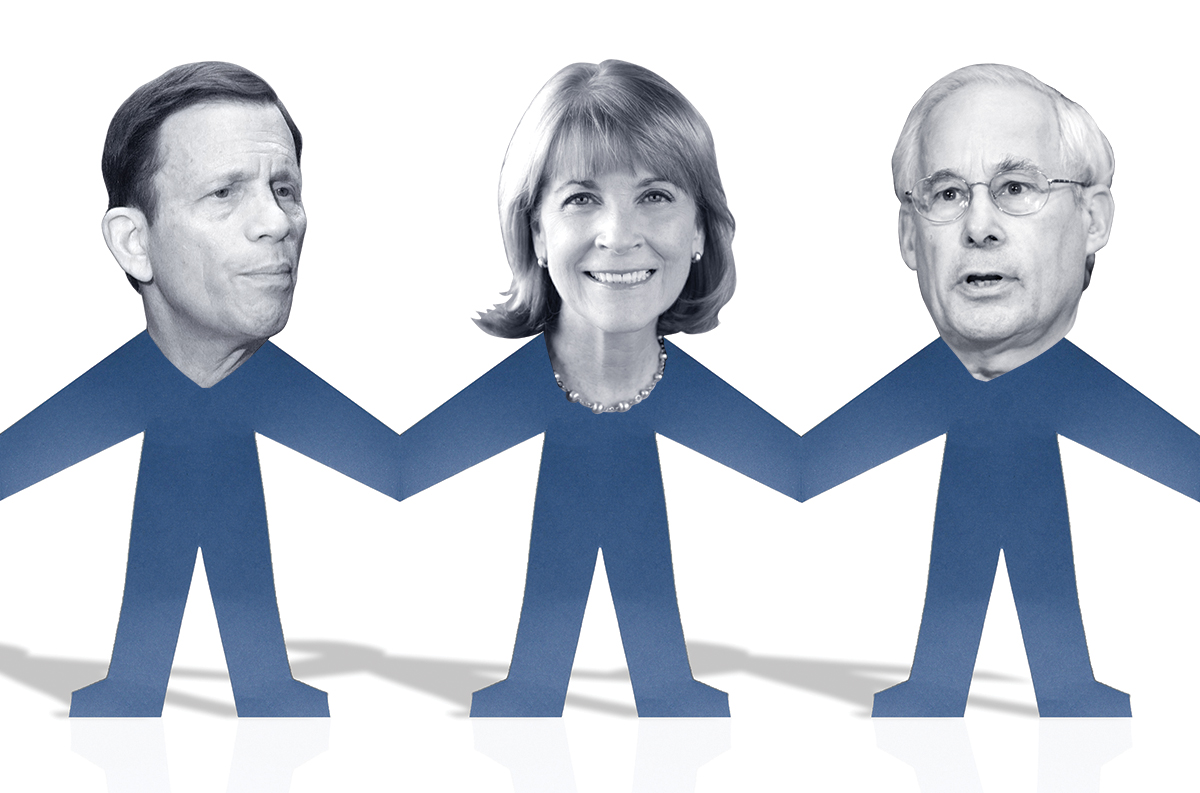

Photo Illustration by Toan Trinh. Photographs by David L. Ryan/The Boston Globe/Getty Images (Grossman); Courtesy of massdems.org (Coakley); Joshua Roberts/Bloomberg (Berwick)

On the 13th day of June, whistles and cheers filled Worcester’s cavernous DCU Center, where Massachusetts’ Democrats had gathered en masse to celebrate the life and work of the man who had emerged as the delegates’ clear choice for governor. As they applauded, the man of the moment stepped across the stage to address the crowd. There was just one small problem: Deval Patrick is not running for a third term.

“We are leading today not because we catered to the powerful, not because we kept the finger in the political wind, and not because we avoided the tough issues,” Patrick bellowed, “but because we stood up for what we believed, and governed for the next generation.”

June 13 was a Friday, and what happened that night may have been an omen of what is to come this fall. After a bit of a rough start, Patrick has become a popular governor in what is arguably the most important progressive state in America. As he prepares to leave office, he has a favorability rating of 56 percent. But what comes next will be a far cry from Deval Patrick. With no clear successor—former Lieutenant Governor Tim Murray is not running—a cluttered field of five Democrats had assembled to succeed him, though none of them spoke that evening or shared the stage with Patrick, preventing anyone from basking in his reflected glory. In fact, the governor continues to assiduously avoid the appearance of picking a favorite. By the time the five candidates spoke at the convention the following day, Patrick’s rhetorical flash had dissipated, and none of the candidates—three of whom qualified for the ballot for the September 9 primary election—was able to muster anything nearly as moving as the governor’s oration.

That’s not surprising. There are few politicians anywhere who deliver a speech as well as Patrick—not even President Barack Obama, who had given a graduation address in the same building, just two days earlier, to students from Worcester Technical High. But here’s a terrifying sign if you’re hoping to see a Democrat succeed Patrick on Beacon Hill: Most of the delegates I spoke with in Worcester were more enthused about what the candidates for attorney general had to say than anything coming from any candidate for governor.

What happened? Patrick will be a tough act to follow, and not just with the devoted party activists in Worcester. He has become an oversize presence in the commonwealth, whether reassuring us in his MEMA jacket during a crisis or choking up with emotion as he makes the case for accepting refugee children into the state. As a result of his popularity, his light shines so bright that the candidates are indistinguishable in the glow. All of the remaining Democrats—Attorney General Martha Coakley, Treasurer Steve Grossman, and healthcare executive Don Berwick—fell in step with his positions, if anybody attending the convention cared to notice.

If the Democratic primary has been a tepid affair, lacking in debate over the direction of the state—as it has seemed to me—that has a lot to do with the specter of the current governor looming over the candidates. Call it the Patrick Problem. They can’t, or at least won’t, criticize Patrick, and as a result have melded into identical yes men. Coakley, Grossman, and Berwick face a problem similar to the one that confronted George H. W. Bush in following Ronald Reagan, and that Al Gore faced in attempting to succeed Bill Clinton, says Democratic strategist and Liberty Square Group president Scott Ferson. They’re all essentially running for Patrick’s third term. “Why you?” Ferson says. “Because he can’t run again.”

To get some perspective on what’s different about this race, I went to see someone who’s been through the campaign cycle herself. Shannon O’Brien, the former state treasurer, was the Democratic nominee for governor in 2002. (She lost to Mitt Romney in a bid to succeed Jane Swift.) This is the first time since 1990, she noted, that the state’s Democrats have had to choose a successor to an incumbent governor from their own party.

Traditionally, incumbency is an asset, but it may not be helping this time. For one thing, during Patrick’s eight years as head of the state party, he’s focused on activating grassroots liberals—a strategy that has resulted in a party infrastructure that rigidly enforces his ideological views, and expects the same from its candidates.

At the Worcester convention, it was clear how little room is left for moderates. Joe Avellone, for instance, who opposed both single-payer healthcare and an indexed gas tax, could not muster nearly enough support to earn a spot on the September ballot, even with help from powerful supporters like Boston Congressman Steve Lynch and Worcester Mayor Joe Petty. The result: a listless trio of candidates with nearly identical platforms, unable to distinguish themselves on policy.

Also, O’Brien points out, it’s a lot easier to talk about new directions when you can criticize the current governor. However, these three can’t afford to. For one thing, whoever wins will desperately need Patrick’s endorsement in the general election. And for another, it is nearly impossible to make political hay with primary voters out of criticizing a governor with Patrick’s popularity. “That’s why I think you’re not seeing as much intensity,” O’Brien says.

When Grossman dared suggest in June that Patrick deserved only a B-plus grade, he was taken to task by Coakley, among others. In July, it was Coakley’s turn to walk the plank and offer a modest critique of the governor’s tenure: She promised not to have any reprise of the Annie Dookhan crime-lab scandal under her watch. The result? Not only did Grossman slap her down, but Patrick himself also jumped in, calling her comments “foolish.” “You have Democrats who are loyal to a popular incumbent,” O’Brien says. “So even pointing out differences can be uncomfortable.”

In fact, the Democratic candidates spend much of their time promising not to do much of anything but follow Patrick’s current direction. Since fiery criticism of the incumbent has been replaced by full-throated agreement on every issue, it’s been as colorless and calculated a primary race as I’ve witnessed in the 20 years since Mark Roosevelt won the right to be trounced by Bill Weld.

On a sunny Wednesday in July, I stood outside at Assembly Row to watch Somerville Mayor Joe Curtatone endorse Grossman. Standing in a small plaza in front of an ice cream parlor, the candidate proudly declared that “this campaign is about one thing: who will build on Deval Patrick’s foundation.” With no one to criticize and no controversy, it’s not surprising that Grossman didn’t exactly snatch the attention of the families lined up next to a giant giraffe near the Legoland entrance across the street. Nor did Grossman—the state treasurer, holder of the Democratic Party’s official endorsement, and recipient of the most contributions and endorsements in the race— attract much media to one of the biggest endorsements of the summer. Only Sharman Sacchetti of WFXT, a Wicked Local reporter, and I bothered to show up. As usual, Grossman spoke too long about himself. Then he asked if there were any questions. There weren’t.

Likewise, when I caught up with Grossman a few weeks later, he was chatting with potential voters through an interpreter at the Milford Portuguese Picnic. After each brief conversation, he infuriated the translator by darting back to me to explain how the story he’d just heard spoke directly to one of his themes or policies.

“They are the story of Massachusetts,” he said of one hard-working Methuen family, whose two children will be able to attend their city’s new high school, financed largely through the Massachusetts School Building Authority in Grossman’s office.

But in truth, there was little exciting or new about what Grossman had to say, despite his efforts to distinguish himself as an experienced job creator. Instead, he was once again simply casting himself as the candidate to carry on Patrick’s work, saying, “Deval’s created a strong foundation.” Missing an opportunity to separate himself from Patrick and his fellow candidates, Grossman was careful not to shine a negative light on unemployment numbers or any unfinished business.

The previous day, I was with Coakley at the launch of her Latinos por Coakley initiative at O’Neill Park, in Lawrence, when I asked her what she thought this campaign is about. Choosing her words carefully, Coakley said, “It’s about maximizing the opportunities here in Massachusetts, with our knowledge economy and our great school systems, to do even better, and to build an economy on our terms, in every region of the state.” These are the types of public events Coakley has typically done over the summer: quick appearances to boost the morale of a small group of enthusiastic supporters, usually right before they hit the streets and knock on doors asking for support. It seemed clear to me that Coakley was walking a fine line between praising the economic gains under Patrick and suggesting that more must still be done. Still, grinding out a message that things are good but could be better is hardly a compelling way to galvanize voters. In fact, in a primary where Coakley has led by a wide margin throughout, it feels more like she’s laying the groundwork for the general election than a real play to win the primary.

As I asked political observers about the seemingly substance-free nature of the election so far, many put the blame on cautious, uninspiring candidates, particularly Coakley, who they say is playing safe with her lead. “I think it’s by design,” says Democratic consultant Dan Payne, who did some work for independent candidate Jeff McCormick earlier in the campaign. When it comes to the primary, Payne says, “Coakley has no reason to make it about anything.”

On July 15, I asked Berwick the same question about the meaning of the election. Despite positioning himself as the most liberal candidate in the race, he too answered in terms of moving forward on Patrick’s progress—and did so in very Patrick-esque language. “I’m trying to make this election about a sense of values,” he said. “If we have a campaign that’s just about maintaining things the way that they are, or walking away, that’s not good enough for me.”

On paper, Berwick is the most Patrick-like candidate. A first-time hopeful like Patrick was in 2006, Berwick also has an impressive White House post on his résumé: administrator for the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Similarly, Patrick had been assistant attorney general for the Civil Rights Division.

But so far, it doesn’t seem as though Democrats are looking for another Patrick, circa 2006. Back then, they were looking for a change after four years of Mitt Romney. Today, they want the 2014 Patrick, who is the face of Beacon Hill. They want the status quo.

For his part, Patrick has meticulously avoided taking sides in the Democratic primary. Thanks to former Lieutenant Governor Tim Murray’s forced withdrawal from the political arena, Patrick has no natural successor, and he has managed to stay out of the fray. But that will likely change, dramatically, once the primary concludes and a Democratic nominee is chosen on September 9.

Whatever Patrick’s future plans, he knows that his legacy depends in large part on a Democrat winning in November. After all, as Ferson says, the election will be seen as a referendum on Patrick. Just as Patrick’s victory over Lieutenant Governor Kerry Healey in 2006 was seen more as voters sticking a boot up Romney’s backside on his way out of office than as a ringing endorsement of all Patrick had promised during his campaign, this election will be Patrick’s ultimate report card. Patrick’s legacy will also depend on whether the programs he started in education, criminal justice, and healthcare carry on, or are reversed under a Republican before they bear fruit.

The emphasis on Patrick’s legacy is the silencer on this election cycle: It keeps his potential successors from criticizing him, while he tacitly complies by staying neutral. Yet there’s a bitter irony. Patrick’s reluctance to throw his weight behind a candidate in the primary, according to Democrats I’ve spoken with, has not only contributed to the lackluster campaign but is also inadvertently playing into the hands of expected Republican nominee Charlie Baker.

Speaking at the state GOP convention in March, Baker was clear that he wants this election to be about nothing, or at least not about policy issues. In fact, he’s gone out of his way to erase the policy differences between the Democrats and himself on a range of subjects, from climate change to accepting undocumented children. Instead, Baker has said, he wants this election to be about competent management. Rattling off a checklist of Patrick-administration sins—the Department of Children and Families fiasco, the healthcare-exchange website disaster, and others—Baker is already casting the race as a choice of who will be the better CEO to run the state. Baker’s running mate, lieutenant governor hopeful Karyn Polito, echoed that sentiment when I ran into her at the Milford Portuguese Picnic. “The position of governor is really the big manager of the state,” she said, adding that voters want accountability “after one party [has controlled] every aspect of the government.” So while Democrats must figure out a way to work around Patrick’s looming presence, Republicans delight as they get the chance to tell voters about the problems he’s left for somebody to clean up, with virtually no counter. The Democratic convention in June, by contrast, included only occasional mentions of the expected Republican nominee. There has been very little attempt to clearly spell out the choices voters will face in November—again, as O’Brien notes, partly a function of Democrats being the party in power. “When you run against a nonincumbent, it’s like running against air,” she says. A lot of hot, stagnant air. While the Democratic primary candidates are all running in circles vying for the “most like Patrick” award, the important policy debates and differences are floating out to sea unnoticed and unexamined. Voters may be resolute in the desire for a third-term Patrick to lead the state in 2015, but the effect of the Patrick Problem, I fear, is that a field of indistinguishable candidates will not draw voters to the polls. After September 9, however, that should all change.

Whoever wins the Democratic primary will need to land punches, raise the kind of big money absent from the candidates’ current fundraising efforts, and galvanize minorities and young voters to show up for the November vote. For all three tasks, nobody will be more effective than Patrick.

So expect to see and hear a lot from the outgoing governor this fall, as he makes the case to reward him with a third term—when the Patrick Problem becomes the Patrick Advantage.