City Officials Want to ‘Level the Playing Field’ for Uber, Cabs

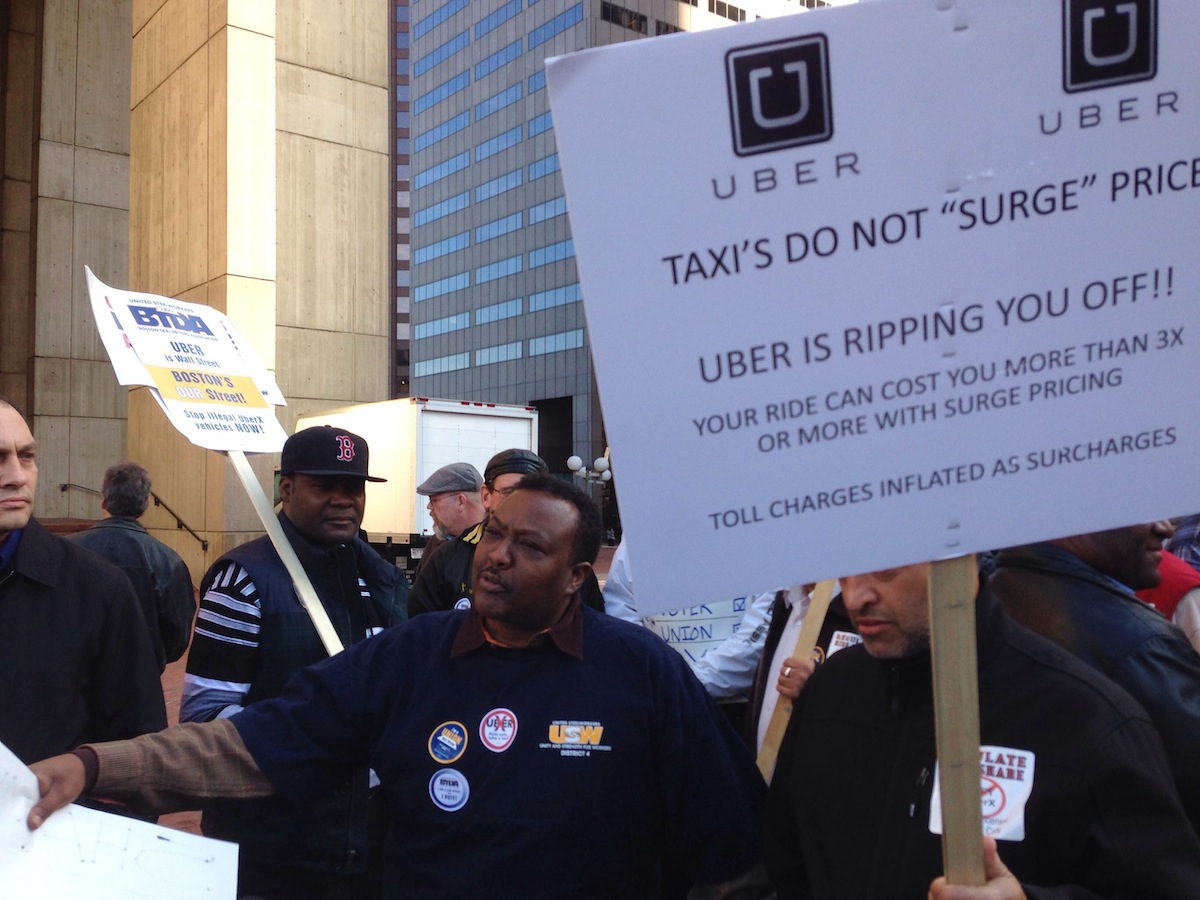

Protests that started on the Government Center plaza Monday afternoon quickly spilled into a packed hearing room at City Hall, where hundreds of people on both sides of the argument about whether on-demand livery services like Uber and Lyft should be better regulated either aired their grievances, or showed support for the ride-sharing companies.

“City Hall needs to be responsible,” said Ahmed Farah, a fired-up union cab driver who was one of many who picketed Uber and Lyft outside of the municipal building. “I want them to change their attitude for the taxi industry. The taxi industry is a death. They are dead. Totally dead. It’s the Uber, we need our rights. That’s what we are talking about. They need to change the [regulations] the way they regulate to us.”

The protests at the plaza came prior to a meeting of the City Council’s Committee on City, Neighborhood Services, and Veteran Affairs about ride-sharing regulations. On one half of the brick landing outside of City Hall’s front doors, Uber representatives huddled together holding signs that read “Boston Loves Uber,” handing out free coffee and donuts. On the other side, cab drivers and union members were waving posters calling for officials to shutdown the app-based ride-share services.

Farah, who was perhaps the most vocal representative on the side of the taxi industry, said that he’s not only losing customers, but he’s also losing money, and goes home at night with a lot less than he did before Uber and Lyft hit the streets. “There is not any regulation for Uber. It’s not fair,” he said.

Ralph Belizaire, who has been a cab driver for more than a year and a half, says he’s having the same problems, and that it’s UberX that “needs to be out” of the equation, in order to bring fairness to both sides. He said he used to make around $300 per night picking up passengers, but now he makes “$100 if I’m lucky.”

Belizaire reiterated that cab drivers calling for Uber regulations are mostly concerned with the rollout of UberX, and how those drivers can operate personal vehicles without medallions or special plates, unlike a taxi. “They need to have a livery [plate] at least,” he said. “We have no problem with that. But if my wife started picking up customers with her car, that’s not fair to us. We pay $700,000 for a medallion, and the city should know that.”

The prospect of having UberX drivers go through the livery process, much like Uber black car and SUV services must do, was one of the topics that city officials and police officers from the department’s Hackney Unit touched upon early on at the public hearing, which lasted more than four hours.

Boston police said they have doled out more than 700 citations to illegal vehicles-for-hire this year alone, a drastic increase from the number of violations they handed out in the two years prior, though they couldn’t say how many of those citations were specifically for UberX drivers. A ticket for operating a service like UberX, if caught by the police, costs around $500, and can lead to an arrest and towed vehicle, police said during the hearing.

Police said passenger safety tops their list of concerns and priorities as the city begins to discuss future regulations, because the department has no clue who is behind the wheel of an UberX vehicle at any time, despite claims by the company that each driver is subjected to a thorough background check.

Aside from the issue about livery plates, perhaps the most agreed upon point during the initial conversation before public testimony got underway was that the city needs to “level the playing field” for everyone who makes a living by dropping off and picking up passengers.

But the best approach for such a move varied greatly between City Councilors.

“Uber drivers, they’re not going by the same rules as the taxi industry, and that industry generates money for our city so our city keeps moving,” said Councilor Frank Baker, who admitted he doesn’t use Uber. “I think they have to pay their fair share, and play by the same rules as all of the drivers. Uber and Lyft should be paying to do business here.”

Councilor Tito Jackson, one of several elected leaders who said he uses Uber to get around, focused his attention on possibly lowering credit card transaction fees that cab drivers are forced to pay out of pocket, so they don’t try and shy away from customers who don’t want to pay cash. “That fee is what leads to conversations about ‘are you paying cash or credit,’ and puts cabbies at a disadvantage,” he said. “We should think about maybe taking some fees away from drivers, who are bearing the highest brunt of the fees.”

Councilor Michelle Wu, who also noted that she uses Uber, said whatever the outcome of the regulations, they shouldn’t weigh too heavily on one side, and definitely shouldn’t keep businesses from being successful. “Boston is a place where regulations shouldn’t squash innovation. Ride-sharing, yes, needs to be safe and ensure the well-being of passengers across the city, but it shouldn’t face over-burdensome regulations,” she said.

City Council President Bill Linehan, who called for the hearing, said he hopes all of these concerns—and more—are taken into consideration moving forward, and that the mayor’s recently appointed Taxi Advisory Committee examines all aspects of both Uber’s operations, and the existing taxi industry and how it’s managed by the city.

“This is the first time I can think of that the entire city is focusing on this particular issue,” said Linehan. “This issue is not settled. We haven’t figured out a true level-playing framework for us to operate rides-for-hire in our city, so we need to make adjustments. We are all hear to listen, not to debate. This is about testimony, gathering information, and coming away with a position, maybe a regulation, and maybe an ordinance.”