Back to School. Way Back.

Archaeologist Joe Bagley will lead a dig on the original campus of Boston Latin School this summer. (Photograph by Toan Trinh)

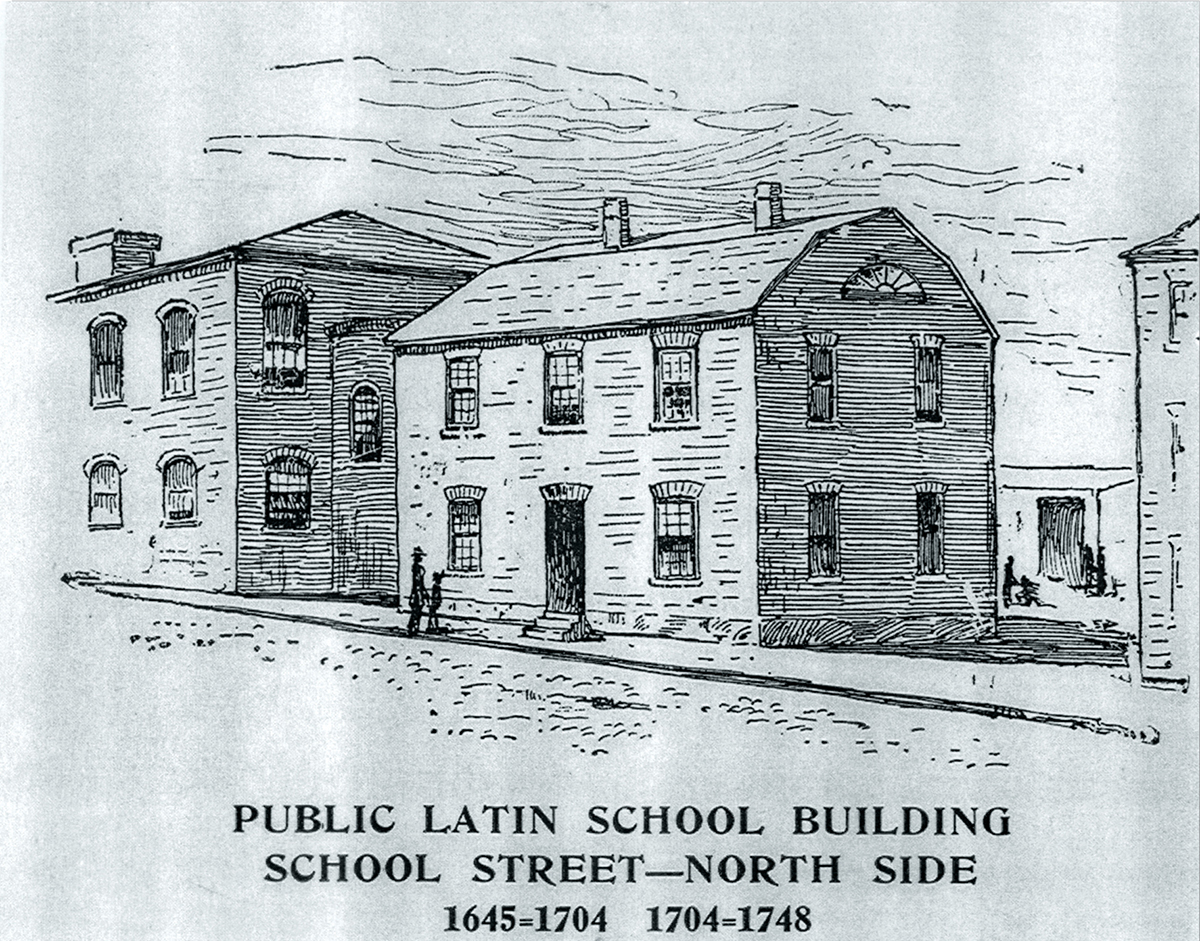

This winter, an archaeologist’s dream fell into Joe Bagley’s lap: a file full of centuries-old deeds for a small plot of land in downtown Boston. The documents, discovered by an intern, revealed that the original schoolmaster’s house for Boston Latin School stood near the corner of what is now School Street and City Hall Avenue.

The first public school built in North America, Boston Latin spit out a brain trust of revolutionaries over the years: Ben Franklin in 1714 (okay, he dropped out); Sam Adams in 1729; and John Hancock in 1745. Glimpsing the life of this institution’s early schoolmasters, Bagley knew, would only add to the legacy of the school and the city itself.

But what really excited him were the detailed plans from 1701 to replace the schoolmaster’s house using the existing foundation. In other words, they’d built a new house atop the old one.

Archaeologists aren’t known for their alacrity, especially when the dig site happens to be in a metropolis bogged down by bureaucracy and commercial interests. But Bagley knew he had something special.

Part of what made the project so intriguing was a deed from 1809 showing that the land had been sold to the county for the construction of a courthouse. One of the stipulations of the sale was that no future buildings were to be erected on the grounds of the former schoolhouse.

From there on out, this morsel of property in the shadows of King’s Chapel and Old City Hall evaded centuries of development. “It just seems like one of the incredibly rare spots in Boston that’s been used once and never reused again,” Bagley says. If he’s right, the backyard of the schoolmaster’s house will be intact and buried beneath. The ultimate goal is to pinpoint the privy, or the outhouse.

“That should give us an extremely detailed data set for the family, which would include everything from the garbage they were producing…to the bones of the animals they were eating, to the seeds of the fruits and vegetables they were eating, to the parasites in their guts from the human waste that would be found,” Bagley explains. (For the record, Bagley confirms that centuries-old human excrement smells as foul as one would imagine.)

“We have one of the best opportunities left in the whole city to look at a 17th-century site,” says Bagley, who will be supervising the dig all summer. “And it’s in the heart of the city.”

illustration courtesy of boston latin school