Whom Hillary Clinton Should Meet with About Drug Abuse in Massachusetts

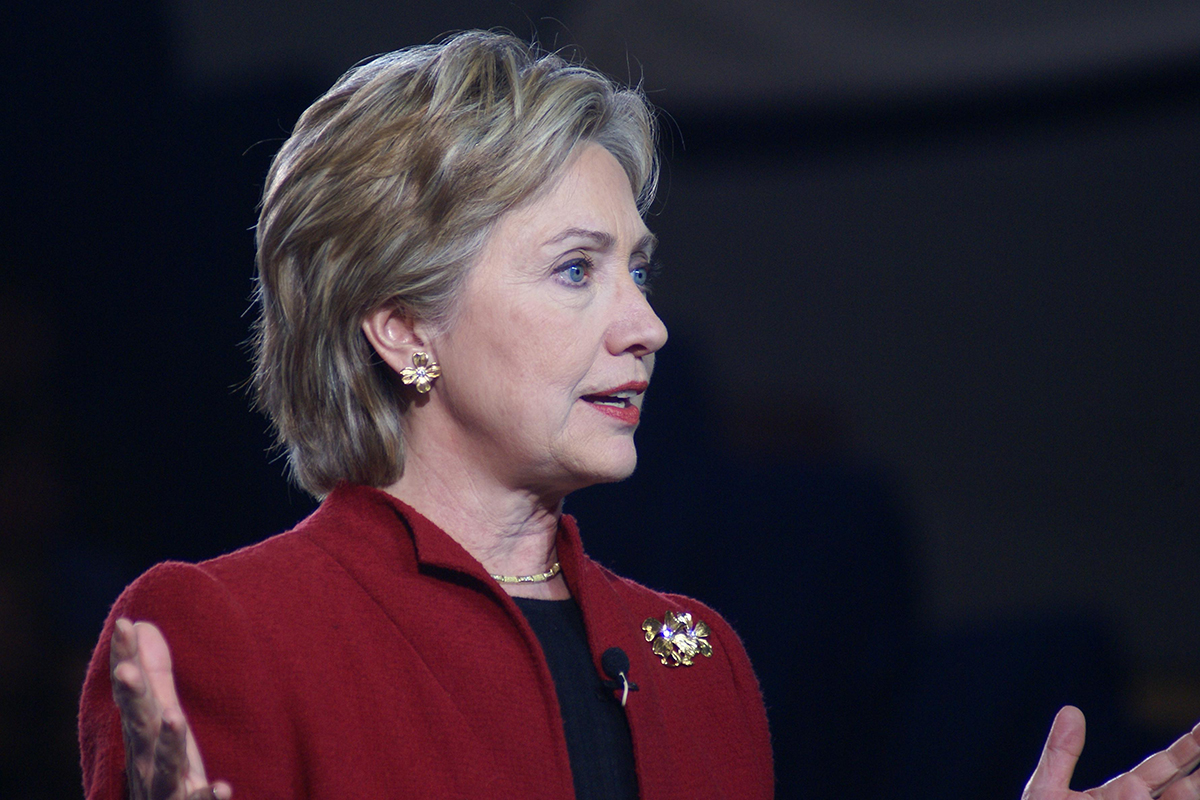

Hillary Clinton Photo by Marc Nozell on Flickr/Creative Commons

On Thursday, Hillary Clinton is coming to Boston to talk about substance abuse at a community forum with a couple of people who know way too much about it: Mayor Marty Walsh, who has firsthand experience with addiction and recovery, and Attorney General Maura Healey, who recently struck a deal that requires Amphastar Pharmaceuticals to cough up $325,000 to offset the surging costs of Narcan, the lifesaving drug that reverses overdoses.

Clinton’s meeting with Walsh and Healey is great in that it marks one of the first major attempts from any presidential candidate to push the issue of addiction onto the campaign trail. But as the steady tide of deadly overdoses shows, conventional strategies are failing.

That said, here are three experts who could give Clinton a radical education on the challenge we’re up against.

Gloucester Police Chief Leonard Campanello

Since June 1, Campanello has been granting amnesty to addicts who come to his station house and want help. Instead of jail, he gets them into treatment. In the first three months of the program, his department placed 145 people into care. For perspective, consider that for all of 2014, the Essex County drug diversion program enrolled a total of 59 people.

Showing that police can be a vital access point for addiction treatment was only the first step. Campanello recently—and successfully—trolled the pharmaceutical firms on Facebook, and now he has the insurance companies and prescription-happy docs in his crosshairs. A major indicator of Campanello’s success: Other police departments, from Massachusetts to Illinois, are following his lead.

Dr. Camilla Graham

With overdoses occurring every day, it’s hard to think about the long-term effects of the heroin crisis, let alone prepare for them. But that’s exactly what we need to be doing, says Graham, an infectious disease doctor at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center. The ugly truth is that the tidal wave of injection drug use has ushered in a burgeoning hepatitis C crisis, the costs of which will be staggering. While effective treatments exist, they are priced at nearly $100,000 and very few people can access these medications in a timely fashion. When left untreated, hep C leads to numerous deadly maladies, including liver cancer and cirrhosis.

“This medicine is so well tolerated and it works so well in most patients that the only reason you would not treat everybody, once they’re ready, willing, and able to be treated, is because of the price. There is no other reason,” Graham says.

Sarah Mackin

As a manager at one of Boston’s busiest needle exchanges, Mackin regularly meets with people who have fallen through the cracks of our patchwork treatment system. What bothers her most is that nearly everyone she encounters after detox, whether they completed it successfully or not, is adrift without a clue of what to do next.

“There’s not one program that I know that does this consistently and well—that connects people to care, doesn’t discharge people with absolutely no follow-up plan or aftercare plan,” she says. “That gap—any gap in care in that continuum—is almost a death sentence.”