Sneaker Wars: Converse vs. New Balance

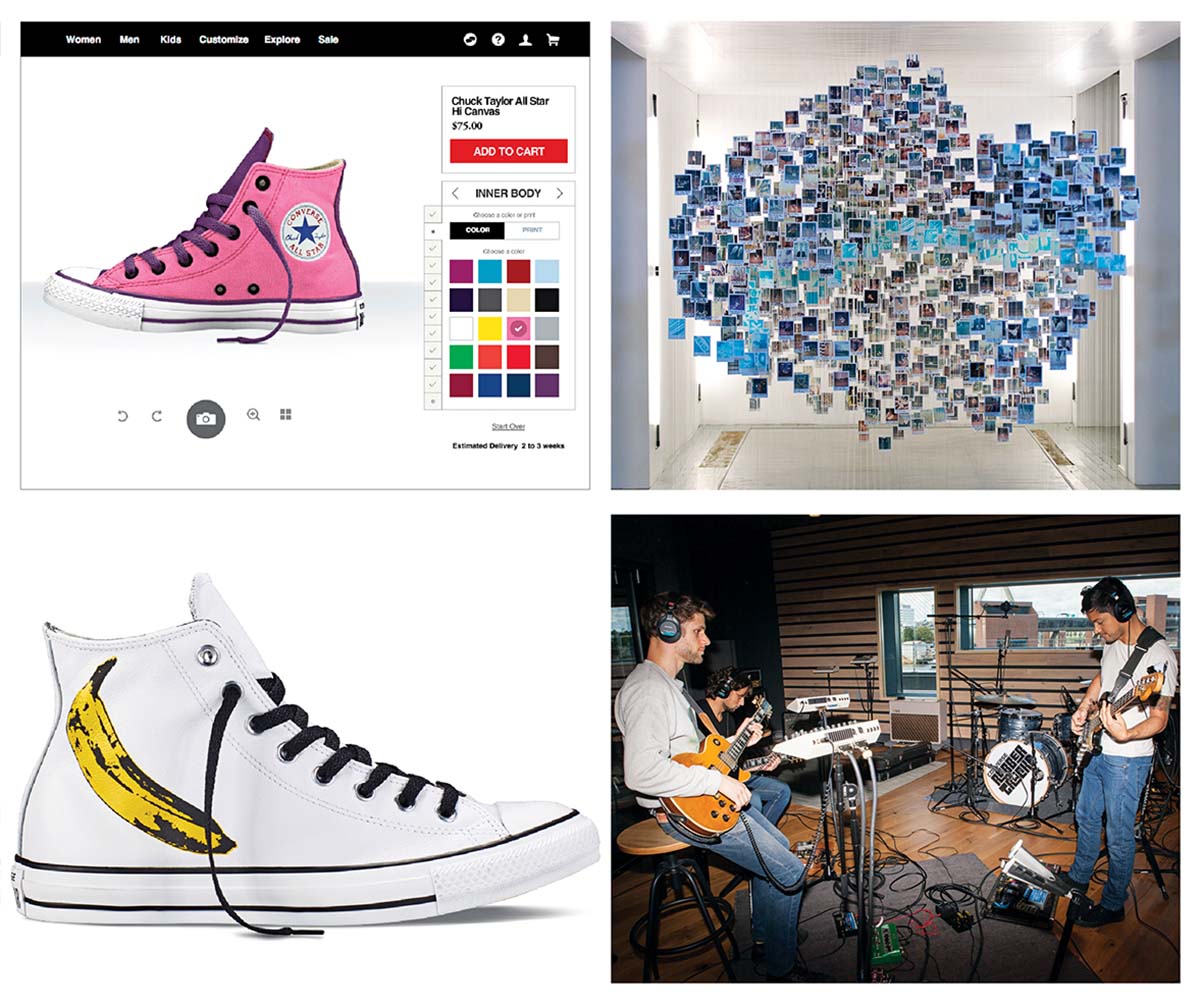

The Rebirth of Cool: How does a sneaker company succeed without sports? By emphasizing its creative-class cred. | From top left: Calhoun introduced “Design Your Own Chuck Taylors,” which let customers customize their kicks, spearheaded the global “Made by You” campaign featuring art installations across the globe, and launched an Andy Warhol collection. To strengthen Converse’s ties to rock ’n’ roll, he opened Rubber Tracks recording studios in New York, São Paulo, and Boston, which offer local musicians free use of state-of-the-art equipment. / Photographs courtesy of Converse

No sneaker embodies the rebellious American spirit like the Chuck. The simple, flat-soled shoe with a white toe bumper, black stripe along the bottom, and All Star patch has proudly appeared on the feet of World War II Army cadets, Elvis Presley, Andy Warhol, the Sharks and the Jets in West Side Story, the Ramones, Hunter S. Thompson, Michael J. Fox in Back to the Future, Kurt Cobain, and Justin Bieber. “Wearing something with a swoosh or a puma has the perception of being corporate,” says Jay Gordon, founder of the über-hip Boston boutique Bodega. “Chucks are much more antiestablishment. They are rock ’n’ roll.”

So far, customers around the world have bought more than a billion pairs of Chucks. They’ve become iconic. That success, though, has led to an “explosion of knockoff activity,” Calhoun says. During his first three years as CEO, he played a fruitless and “endless Whack-a-Mole game,” he says, sending hundreds of cease-and-desist letters to companies he suspected of selling rip-offs. Finally, in October 2014, Calhoun took a bold step toward choking off competitors, suing 31 companies for copyright infringement. Converse also filed a complaint with the International Trade Commission (ITC), which expedites cases and has the authority to prevent shoes that are considered counterfeit from entering and being sold in the country. The company argued that the Chuck’s combination of toe cap, toe bumper, and midsole stripe had over the course of nearly a century developed what lawyers call a “secondary meaning”—a strong association in the public’s mind between an image and the company manufacturing it. Like the McDonald’s golden arches or Disney’s mouse ears, Converse argued, shoes with the telltale toe cap, toe bumper, and stripe could not be mistaken for any other brand but Converse.

The company’s legal argument was rooted in its origins. In 1908, a New Hampshire native named Marquis Mills Converse founded the Converse Rubber Shoe Company in Malden. In the beginning, his only products were waterproof boots; later, he expanded into tennis shoes to keep his workers employed year round. In 1917, he debuted the world’s first performance sneaker for a little-known sport that was beginning to catch on in the Northeast. He dubbed his basketball shoe the Converse All Star, complete with a rubber toe cap and bumper. For four years, sales remained slow. Then, in 1921, a scrawny 20-year-old jump shooter from Indiana named Charles “Chuck” Taylor convinced Converse to hire him, minting the country’s first player endorsement. Taylor advised improvements on the shoe’s ankle support and traction, and in 1932 the company stitched Taylor’s signature into the All Star heel patch. The shoe barely changed for 80 years.

Over time, Converse became synonymous with basketball. Chucks were on the feet of the U.S. men’s team when it won gold at the 1936 Olympics in Nazi Berlin. Wilt Chamberlain wore them the night he scored 100 points in 1962, and by the mid-1960s, Converse comprised 80 percent of the sneaker industry.

By the end of the 1970s, however, basketball sneakers had become a booming international business, and competitors such as Adidas, Canton-based Reebok, Brighton-based New Balance, and Nike began to outspend and bludgeon Converse into submission. Nike in particular seized the basketball market by paying college coaches unprecedented sums to wear its sneakers. Then came Michael Jordan. MJ was famously wearing Converse the night he sank the National Championship–winning buzzer-beater for the University of North Carolina Tar Heels, but legendary Nike marketing executive Sonny Vaccaro, a.k.a. “Sole Man,” poached His Airness by paying him $500,000 a year for five years. Up until that point, the highest contract had been between New Balance and James Worthy, for a measly $150,000 a year for eight years.

The Jordan deal helped catapult Nike into the annals of pop-culture history. It became the world’s most profitable athletic shoe company, and flung Converse in the opposite direction. Converse was slow to embrace even simple innovations such as leather shoe construction: Within 10 years, the company was on the skids. In 1995, Converse dropped its running, outdoor, walking, tennis, and football categories, laid off 600 employees—20 percent of its staff—and watched its stock plunge to the point where it was delisted from the New York Stock Exchange. Revenue plummeted from $450 million in 1997 to $209 million in 2000, the year before Converse filed for bankruptcy. Just when it looked like the company was going to become a footnote in sneaker lore, Nike swooshed in and bought Converse for $305 million in 2003, hoping to remake the brand it had helped crush.

Standing atop Converse’s sleek new headquarters overlooking the Zakim Bridge, CEO Jim Calhoun takes aim at the competition as he lifts the Chuck Taylor to new heights. / Photograph by Trevor Reid

For a guy in charge of one of the hippest shoes ever made, Calhoun doesn’t exactly embody the essence of cool. His work uniform is a blazer and jeans—coupled, of course, with a pair of special-edition Chucks. And even when he’s hyping his flagship product to a room full of musicians and artists—his target clientele—he speaks in corporate tones and comes off as studied and out of place. Calhoun practically admits that he’s the last person on earth he ever would have imagined leading Converse into the 21st century.

Calhoun grew up in Dedham and spent much of his childhood on the sidelines of a basketball court, watching his father coach the Northeastern University men’s basketball team. It’s no surprise that Jim Calhoun Sr.’s ferocious competitive spirit rubbed off. “I love to compete,” Calhoun admits. His father would go on to lead the University of Connecticut to three national titles, and Jim Jr. frequently refers to him as his hero.

As a young man, though, Calhoun struggled to measure up to his father. While his younger brother, Jeff, played for their dad at UConn, “at 5-foot-10 and immensely average from an athletic perspective,” Calhoun says, “I knew early on that basketball probably wasn’t going to be in my career.” After graduating from the blueblood prep school Noble & Greenough, he enrolled at Northeastern and followed his dad to UConn, where he studied psychology. When Calhoun graduated in 1989, he had no plans to become an executive, but says he knew “If I can’t be an athlete, I’m going to go into this thing called business.” He hoped to establish a career far away from his legendary father’s home turf and then, one day, return to New England.

Unlike his father, though, who coached at only two schools over 40 years, Calhoun bounced from one company to another, making stops at Nautica, Disney, and Dockers. He even worked at Nike in the mid-1990s as a product manager for college basketball apparel before landing back at Nike in 2011 as CEO of the California-based skateboarding and surfing brand Hurley. Just a month after that, Nike moved Converse CEO Michael Spillane over to Umbro, and asked Calhoun to take his place.

Calhoun quickly set to work on sharpening the brand’s identity. Within a year, he strategically killed Converse’s performance basketball line, upon which the company was practically founded, to free it from competing head-to-head with Nike. He also placed the company’s undivided focus on the shoe with the classic white toe cap and toe bumper. With Converse’s signature basketball line out of the picture, the question for Calhoun suddenly became: How does a sneaker company that is no longer about sports continue to grow?

To Calhoun, the answer was clear: focus on what made Converse unique and cool. He introduced “Design Your Own Chuck Taylors,” which spoke to millennials’ desire for individuality and enabled customers to take control of their own look. He also launched an Andy Warhol collection, and used part of a $7 million media budget on a global “Made by You” campaign featuring art installations in cities across the globe, from Shanghai to London. To strengthen Converse’s ties to rock ’n’ roll, Calhoun opened recording studios in trendy cities such as New York, São Paulo, and Boston—all of them called Rubber Tracks—which offer local musicians free use of state-of-the-art equipment, no strings attached. (The opening party for the Boston studio stretched for a week and included invite-only performances by the Replacements, Slayer, and Chance the Rapper.)

In an effort to attract young talent and inject raw energy into the company, the corporate journeyman knew he needed a sleek new home, one that smacked of hipster cool and embodied the Converse image. So he relocated Converse’s headquarters to a converted brick factory at Boston’s Lovejoy Wharf in May. “If you’re a twentysomething-year-old international designer,” Gordon says, “North Andover isn’t exactly what you’re looking for.”

The best way to describe the new 214,000-square-foot, 10-floor Converse headquarters is corporate hipster nirvana. Calhoun got his wish. When young designers or salespeople interview for a job, he can lure them with a chandelier in the entrance made up of nearly 200 glowing black Chucks dangling from white shoelaces; an employee concierge to book flights and handle dry-cleaning; an expansive lounge and espresso bar; a second-floor gym “powered by Nike”; a deck overlooking the Zakim Bridge; and hundreds of employees with tattoos and perfectly groomed beards, all with Chuck Taylors strapped to their feet.

Calhoun knew there was still more work to do. In 2014, Converse asked customers around the world for feedback. The biggest complaint by far was that Chucks hurt their feet, but by no means did they want the company to start messing with their favorite shoe. Despite the poor cushioning, customers hailed Chucks as the shoe they wanted to be buried in when they died and vowed to renounce Converse forever if it changed. Once again, the message was clear: Don’t fuck up the Chuck.

Calhoun listened, but did not obey, and took his biggest gamble yet: the first major redesign of the Chuck in 98 years. This past July, Converse invited 130 fashion journalists from around the world to a cavernous warehouse on Boston Harbor, where they walked through a circus of floor-to-ceiling neon-green strobe lights to see the Chuck II for the first time. The sneaker maintains the timeless look, but has a sturdier microsuede lining, a gum-rubber sole, a memory-foam tongue, and the vastly superior Lunarlon sock liner invented by Nike. “They feel like real shoes now, instead of like shoddy canvas sacks for feet,” wrote Gizmodo. The Verge praised the “ground-up rebuild—like the Galaxy S6 of sneakers.” Katie Abel, global news director of Footwear News, told me that the Chuck II “opens the door to first-time consumers and resparks interest in old consumers.” Once again, Chucks were positioned at the center of rebellious, artistic youth, just like in the 1950s. Except it was 2015, and nearly every size and color of the Chuck II sold out in a single day.