How MIT’S Divestment Protesters Spent Thanksgiving

Elisa Boles, center, an undegrad at MIT, brought her parents from California to the sit-in on Thanksgiving night.

On Thanksgiving, they ate pie in MIT’s corridor of power. They greeted supporters from Seattle, welcomed parents from San Francisco, and exchanged pleasantries with university president Rafael Reif—the same figurehead they’re trying to grind down through a round-the-clock sit-in that has now stretched for 36 days and shows no signs of abating.

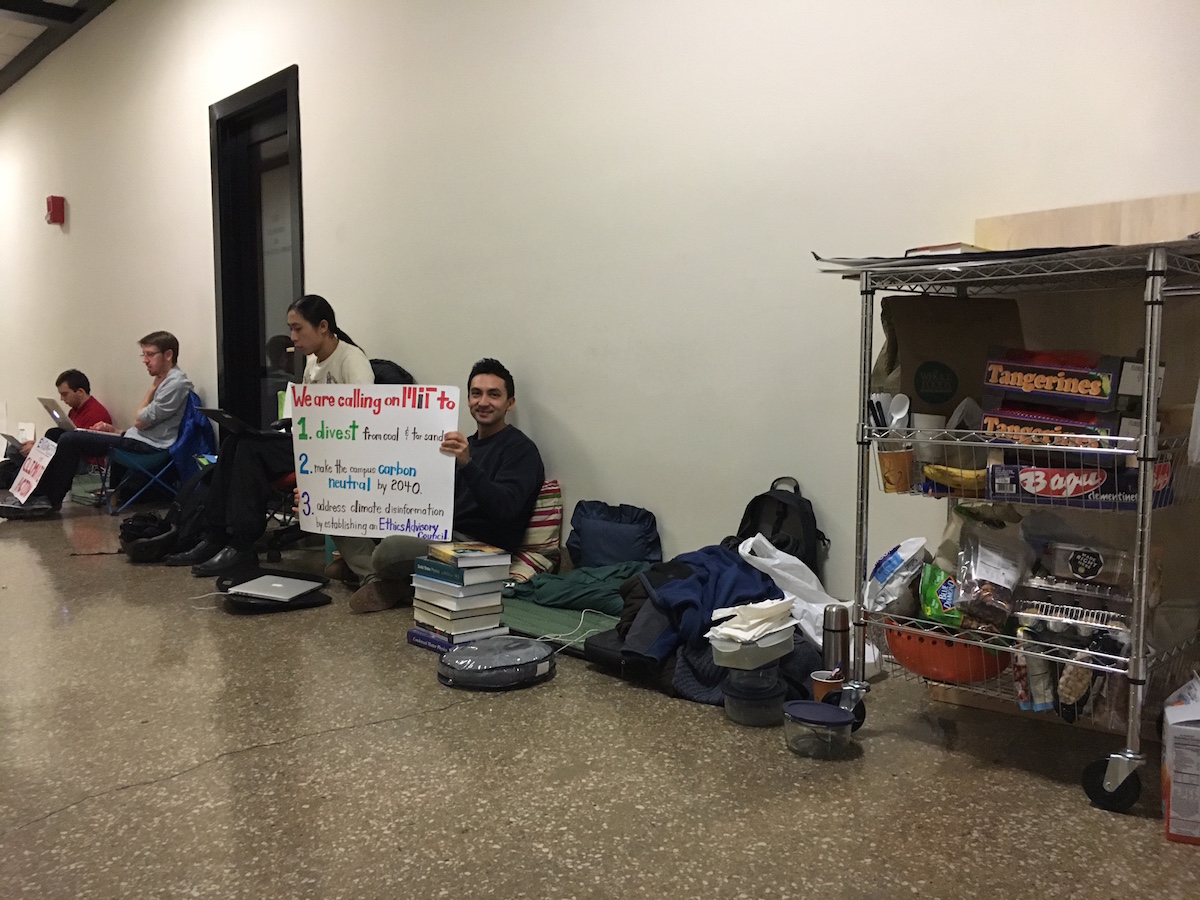

Since late October, dozens of MIT students have carried out a nonstop peaceful demonstration at the entrance of Reif’s office in response to the university’s controversial “Plan for Action on Climate Change.”

Thanksgiving was no different. Throughout the holiday, students took shifts to ensure they always had bodies in the long and otherwise empty hallway. At 9 p.m. a handful of protesters—PhDs and undergrads—congregated quietly. Some plugged away on their laptops, one napped, and others just sat.

Elisa Boles, a sophomore studying civil and environmental engineering, brought her parents, Bob and Christine, who were visiting from California, to the hallway for a few hours. Christine, an alumna who studied architecture, said she fully supported her daughter’s activism.

“MIT is a leading institution,” Christine said. “It’s sad to me that their stance on this is so weak.”

MIT administrators spent more than a year evaluating options and engaging with students, faculty, and alums as they crafted their climate change policy. To foster critical conversation on the issue, the president appointed a special climate change committee, which produced a report last summer that recommended the university divest its endowment from the dirtiest energy firms out there, those that deal in coal and tar sands.

Yet in October, Reif’s office issued its long-term strategy and made clear that it’ll hold on to all investments in fossil fuels. It ignored several other recommendations of the committee, and said that it would focus on working with fossil fuel firms in order to drive research on the issue of climate change.

The release of the plan blindsided Geoffrey Supran and other members of Fossil Free MIT, an activist group that had been driving the divestment debate on campus. They couldn’t believe that the administration had gone against the majority recommendation that MIT divest from coal and tar sands. But even worse was that the administration wholly ignored calls to establish an ethics advisory committee. Such a committee, Supran explained, could play a critical role in evaluating cases in which the university is investing in fossil fuel companies that have directly funded junk science intended to discredit the lifework of some of MIT’s finest professors.

Geoffrey Supran sitting outside Reif’s office on Thanksgiving.

Supran, who was doing a 15-hour-long sit-in shift on Thanksgiving, said the omission of an ethics advisory committee “lit a fire” under students and faculty alike. He pointed to a recent letter that’s signed by more than 90 faculty members who blast the administration for ignoring key recommendations and crafting a plan that “has history against it.”

Those who spent Thanksgiving outside Reif’s office carved out a relatively cozy environment for their protest. They have power strips running from a nearby restroom to charge their computers and a cart full of food to stay satiated. They spent their hours in the hallway doing homework, writing papers, and analyzing data.

Ben Scandella, a PhD candidate who helps quarterback the logistics of the sit-in, estimated that he has spent upward of 200 hours in the hallway since the end of October.

“Some of my best hours of work in recent weeks have been between 2 a.m. and 10 a.m.,” he said. “It’s quiet and I can focus.”

T.Y. Lim, a PhD candidate in the school of management, said the sit-in is not unlike actual climate change negotiations that take place at the United Nations—you’re in a tight, stuffy space under glaring fluorescent lights for hours at a time. It’s adversarial in nature but cordial in practice.

“It drives you a little crazy, but there are things to get done,” Lim said.

Supran said he could not talk about specifics regarding the ongoing negotiations, but said they are meeting regularly with the administration and making progress. He added that much of the focus has been on establishing an ethics advisory committee.

As for the sit-in, Supran doesn’t see it going anywhere and expects they could well spend Christmas in the hallway if needed.

“New people join every day or every other day,” he said. “It’s becoming more sustainable.”