Hard Pressed: Will the Boston Herald Survive?

For more than 50 years, the paper called this South End office building home. / Photograph by Boston Globe/Getty Images

Historically, the Herald has been a product that construction workers and cops picked up at the convenience store to thumb through on break. Lately, though, single-copy sales have taken a beating. In 2011, the paper averaged 83,955 weekday newsstand sales, according to data provided by the Alliance for Audited Media. In 2014, that number was down to 52,467. This should come as no surprise as the rise of conservative news sites such as Breitbart and team-specific sports verticals from the likes of Bleacher Report and SB Nation eat into the Herald’s bread and butter. The paper has gone from competing with the Globe to competing with infinite options for readers’ time. “The Herald is heavily reliant on single-copy readers, people who pick up a copy during the day to have something to read,” says Joshua Benton, director of the Nieman Journalism Lab. “That’s a job that phones do really well now—whether you’re reading news or playing Candy Crush.”

In an era when newspapers have struggled to find multimedia footholds, Herald Radio is a last-ditch effort to remain relevant. The station debuted in the summer of 2013, not long after the paper moved to its current digs, on Fargo Street in the Seaport District. The nucleus of the new newsroom is the small radio booth.

On the surface, radio seems as anachronistic as newspapers, yet conservative talk radio has been a hit for years, and there are distinct advantages that come along with throwing loudmouth Herald personalities on the air. “While I don’t think anyone listens,” says Jim Braude, host of WGBH’s Greater Boston and Boston Public Radio, “I doubt that the paper cares.”

As Braude suggests, the commercial success of Herald Radio isn’t great. Scroll through Herald Radio’s SoundCloud page and you’ll see that most archived shows have been listened to only a few dozen times. But Herald Radio isn’t about numbers or dollars—it’s part of a much larger play for survival, a way to generate scoops that can be spread across multiple platforms on the cheap. The model is simple: Break it on the radio, tweet it out, slap a “just-in” banner on the homepage, bang out a blog post, and tweak it for the next day’s print edition. Not long after Trump’s appearance in July, for instance, the Herald’s Bulldog blog had a post headlined “Donald Trump Calls Handling of Brady Decision ‘Shocking.’” Plus, of course, the paper’s reporters had new ammunition to goad Walsh into a fresh comment and ample fodder to tantalize readers on social media.

The key to making this model work, of course, is luring in big names. Throughout this historically chaotic primary season, just about every major Republican candidate has called in to the station. Prominent locals—Walsh, Governor Charlie Baker, Senate President Stan Rosenberg, Police Commissioner William Evans—also regularly visit the studio. Herald Radio “gets public figures to talk to them that would not have otherwise,” Braude says. “I thought it was ridiculous at first, but it turns out to be the best thing they’ve done, and I think it’s kept them alive.”

The newspaper’s former home is now the site of luxury condos and a Whole Foods with a Herald motif. / Photograph by Sarah Fisher

To get a feel for the Herald in its heyday, I ask Larry Katz to give me a walking tour of the sprawling new Whole Foods just off Herald Street, flanked by three luxury condo buildings in which studios start at $489,000. The development is called Ink Block, and until only a few years ago this was the Herald’s headquarters, the spot where Katz spent some 30 years covering music before retiring in 2011.

Inside the store we stroll past a set of plush leather armchairs and pass under shimmering chandeliers before pausing to look up at a series of giant stainless steel letters reading, “The Boston Herald” that hang above a cooler stocked with imported beers, pierogies, and olives. “I think they came off the chimney,” Katz speculates of the letters’ origin. The Herald motif continues throughout the store, with stylized front pages of old issues serving as backdrops for aisle signs and cashier lights.

Standing in front of a display of chia seeds, Katz recalls editors stamping cigarettes into the carpet and dashing through the city to file copy late at night. Back then the paper had multiple editions, plenty of pages, and deep enough pockets to cover U2 shows in Las Vegas, New Kids on the Block concerts in Europe, and the Grammys in California. “A lot of memories,” Katz says. “A lot of blood, sweat, and tears at this spot; a lot of good times, bad times, happy times, sad times. It was intense.”

Anyone who worked a day in the old Herald building seems to have a dozen stories. I’ve heard about a blood stain on the carpet that staffers didn’t want to get rid of because it was a legacy to a fallen colleague; I’ve been told of an alleged stabbing in the pressroom; and I’ve heard tales of canoodling coworkers whose rooftop romp imploded after an angry wife stormed into the office and threw a punch.

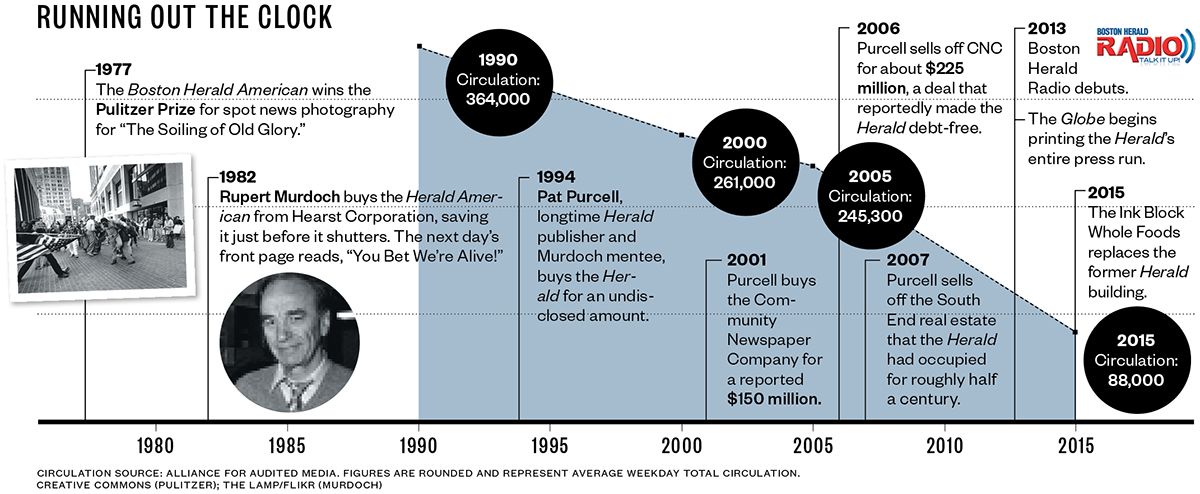

Timeline: A History of the Boston Herald (and Its Declining Circulation)

No day, however, seems as memorable as December 2, 1982. The Herald—then the Herald American—was hours away from shuttering. Its parent company, the Hearst Corporation, had tired of losing readers and money and announced that the paper would be closed or sold. Rupert Murdoch was the only hope, but negotiations had dragged on and were thought to be crumbling. Hearst told the employees to go home. Some staffers hung around the office, unsure if they should clean out their desks or get started on the next day’s edition. Others made their way down to J. J. Foley’s, the Herald’s unofficial watering hole. “We were on the brink of an abyss,” recalls Monica Collins, a former reporter who joined the Herald’s staff in the late ’70s.

After hours of anxious waiting, someone finally rushed into the newsroom and announced that Murdoch had saved the Herald. The next day’s front page exclaimed, “You Bet We’re Alive!”

As if on cue, “That day Rupert Murdoch came into the newsroom, and he was with his second wife, Anna [Torv], and she was wearing this incredible mink coat,” Collins says. She can’t remember the details of the pep talk Murdoch delivered, but when she closes her eyes, she can still envision Torv in her black, full-length status symbol.

Under Murdoch the paper went head-to-head with the Globe and ramped up its mudslinging in the Murdochian manner that has punctuated the tycoon’s tenure with newspapers. Most memorably, the paper unleashed Howie Carr, who through a blend of bulldog reporting and vicious commentary made life hell for elected officials.

Unsurprisingly, the Herald built a Rolodex of powerful enemies, perhaps none as formidable as Senator Ted Kennedy, whom Carr had nicknamed “Fat Boy.” In the late ’80s, when Murdoch was fighting to hold onto his local Fox affiliate, WFXT-TV, Kennedy pushed through legislation that blocked Murdoch from getting a waiver to own a TV station and a newspaper in the same market. To some, it smacked of sabotage. “Kennedy’s political agenda got in the way,” says Brent Baker, vice president for research and publications at the Media Research Center, a conservative-media watchdog organization. “He didn’t like Murdoch, and he didn’t want Murdoch to be a bigger player in Massachusetts politics.”

In response to Kennedy’s legislation—as Dan Kennedy, a Northeastern University associate professor of journalism, has chronicled—the paper sent reporter Wayne Woodlief chasing the senator around the campaign trail. At each stop Woodlief would ask, “Why are you trying to kill the Herald?”

Murdoch ended up selling WFXT. But in 1994, when TV proved a much wiser investment, he bought the station again, which meant having to give up the Herald. Rather than shutter it or sell it off to a stranger, Murdoch invited his mentee and longtime Herald publisher, Pat Purcell, to make an offer. A first-generation Irish American from New York, Purcell had fought his way through the newspaper world; at one point he served as publisher of both the Boston Herald and the New York Post.

The financial details of the deal Purcell and Murdoch struck for the Herald are not public. According to a 2006 article in the Boston Irish Reporter, Purcell recalled Murdoch’s pitch thusly: “I know you don’t have the money, and I understand you don’t want partners, but I would like you to have the paper.”

At last, Herald staffers could breathe easy knowing the paper was going to Purcell. “Pat, God love him, always fought for us,” says Laura Raposa, a former Inside Track columnist who worked for the paper from 1983 to 2013. “He was always on our side.”