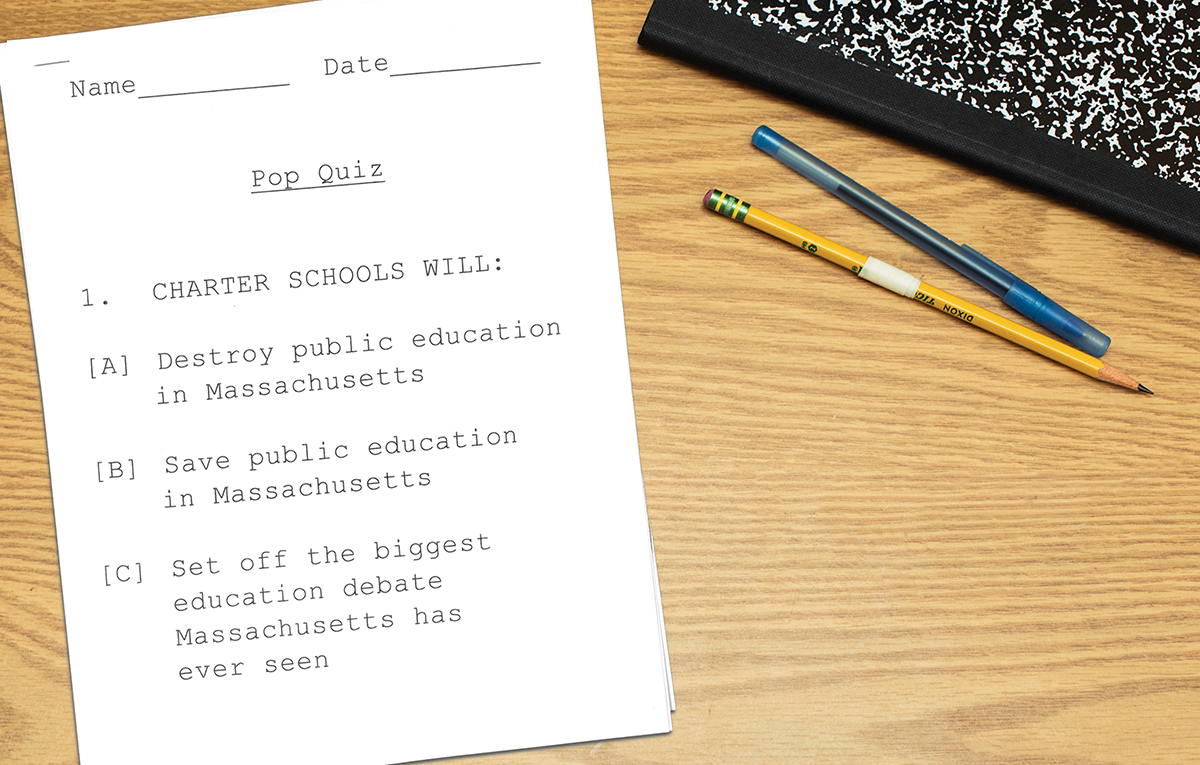

The Great Charter Schools Debate

Photograph by Toan Trinh

This fall, it’s going to get ugly in Massachusetts. We’re prepping for a projected $30 million public fight with all the attendant invective and hyperbole, so keep the kids away from the TV. That’s what I hear again and again as I travel from the State House to Roslindale schools, from noodle shops in Jamaica Plain to downtown nonprofits, Brighton coffee shops, Harvard professors’ offices, and drab union halls in Dorchester. The proverbial poo’s gonna fly, people warn me. And none of this has anything to do with Trump’s comb-over.

In November, Massachusetts voters will decide whether the Department of Elementary & Secondary Education (DESE) can raise the cap on the number of charter schools allowed, or increase enrollment in existing charters in underperforming districts. If the referendum is approved, the city of Boston—which currently has 27 Commonwealth charter schools that operate independently of the district and educate about 14 percent of the student population—will likely see an increase in charters over the next several years. It’s an advance that charter advocates firmly champion but opponents see as another little push in the direction of a very steep cliff.

How did public education get so contentious, even as Boston’s public school system is near the top on every available scoring index of the nation’s major urban districts? Why does Brooke Charter Schools founder Jon Clark, a quiet, straight-talking guy from Wellesley, become slightly unhinged when I share some of the views of the anti-charter folks? What is it about this debate that brings out the tinfoil-hatted paranoia in all of us?

Ideologically speaking, charter schools—which are publicly funded but operate outside of typical district and teachers union rules—are the muddiest of all political issues, simultaneously supported by neoliberals and ultraconservatives, progressives and regressives, hedge funders and immigrants. For those who favor them, charters represent our best hope for improving education. In fact, the pro-charter movement is predicated on the certainty that public education is in crisis, and it lays the blame squarely on government incompetence and union hegemony. Well-run charters, they argue, not only educate children more cheaply, but also more effectively. The data back that up: The average SAT composite score in Boston’s charter high schools in 2015 was 100 points higher (about 10 percentile points) than the district schools’.

Opponents argue that charters are simply a huge, costly distraction from the challenges public education faces, beginning with limited resources. Even if you improve charters, they say, you still need a systematic plan to address the needs of all children, the majority of whom attend regular public schools.

Of course, what makes this debate even thornier is that ultimately it’s not just about educating children. It’s about the role of government and organized labor, and about your faith in data in the classroom. It’s also about how much money you think your kid’s teacher should earn.

Pro- and anti-charter people have been through this all before—they know each other’s talking points and can often pinpoint exactly where a statement, statistic, or argument came from. You’ll hear a lot of well-meaning crap on both sides, as well as plenty of thoughtful analysis based on outdated information. In any event, the sides are strapped in and ready for battle over the soul of public education in Boston.

Charter schools are the biggest social experiment of our time, championed by some of the nation’s wealthiest businesspeople, including Bill and Melinda Gates, Mark Zuckerberg, and the Walton family, of Walmart. Sure, these folks get tax breaks, but they also get something more: the satisfaction that they’re changing the world. Their money is here in Massachusetts, funding advocacy and legislators and boosting pro-charter nonprofits and programs.

Massachusetts’ dance with charters, however, started not with an infusion of Walmart cash, but with a lawsuit filed by a group of students in 1978 arguing that funding inequities had denied them a proper education, a violation of the state’s constitution. At the time, school district budgets were at the mercy of local property tax revenues: Wealthy communities had good schools, and poorer communities made do. Inequality was baked into the equation.

Proposition 2½, the 1980 referendum limiting increases in property taxes to no more than 2.5 percent each year, further crippled each town’s ability to raise money for schools. Some communities, such as Newton and Brookline, have overridden that measure to finance their schools. Others wouldn’t. Or couldn’t. By the 1990s, the disparity in educational quality and infrastructure was pronounced. The 1978 case was finally settled in 1993 in favor of the plaintiffs.

The resulting 1993 Education Reform Act, under former Governor William Weld, decreed that the state subsidize districts as necessary so that all towns and cities could achieve foundation budget spending, a dollar amount calculated using a set formula. (These days, wealthier districts often exceed foundation spending.) The legislation also introduced statewide standardized testing (MCAS) and other structural changes to jump-start reform, especially in Boston, where racism, busing, and white flight had ravaged the school system.

Weld had another agenda item: vouchers. Popular among conservative leaders at the time, vouchers were based on the idea that education money should follow the child. If you opted out of the public school system, you could use your tax dollars to pay for tuition elsewhere. The idea proved too controversial for Massachusetts, but charters emerged as a compromise.

Since 1993, smart legislation has helped maintain high standards for charters in Massachusetts while keeping out the predatory for-profit charter operators that plague other states. From the outset, Massachusetts limited the number of charters it would authorize. In 2000, after contentious debate, the state agreed to raise the cap to 120, including district-run charters. Today there are 81 operating charter schools in Massachusetts—but Boston has hit the maximum allowed under the current district cap. If the referendum passes, it would permit up to 12 new charter schools to open in the state per year, or increase enrollment in existing schools. That’s the decision we’ll have to make at the polls in November.