Does Brookline Have a Problem with Black People?

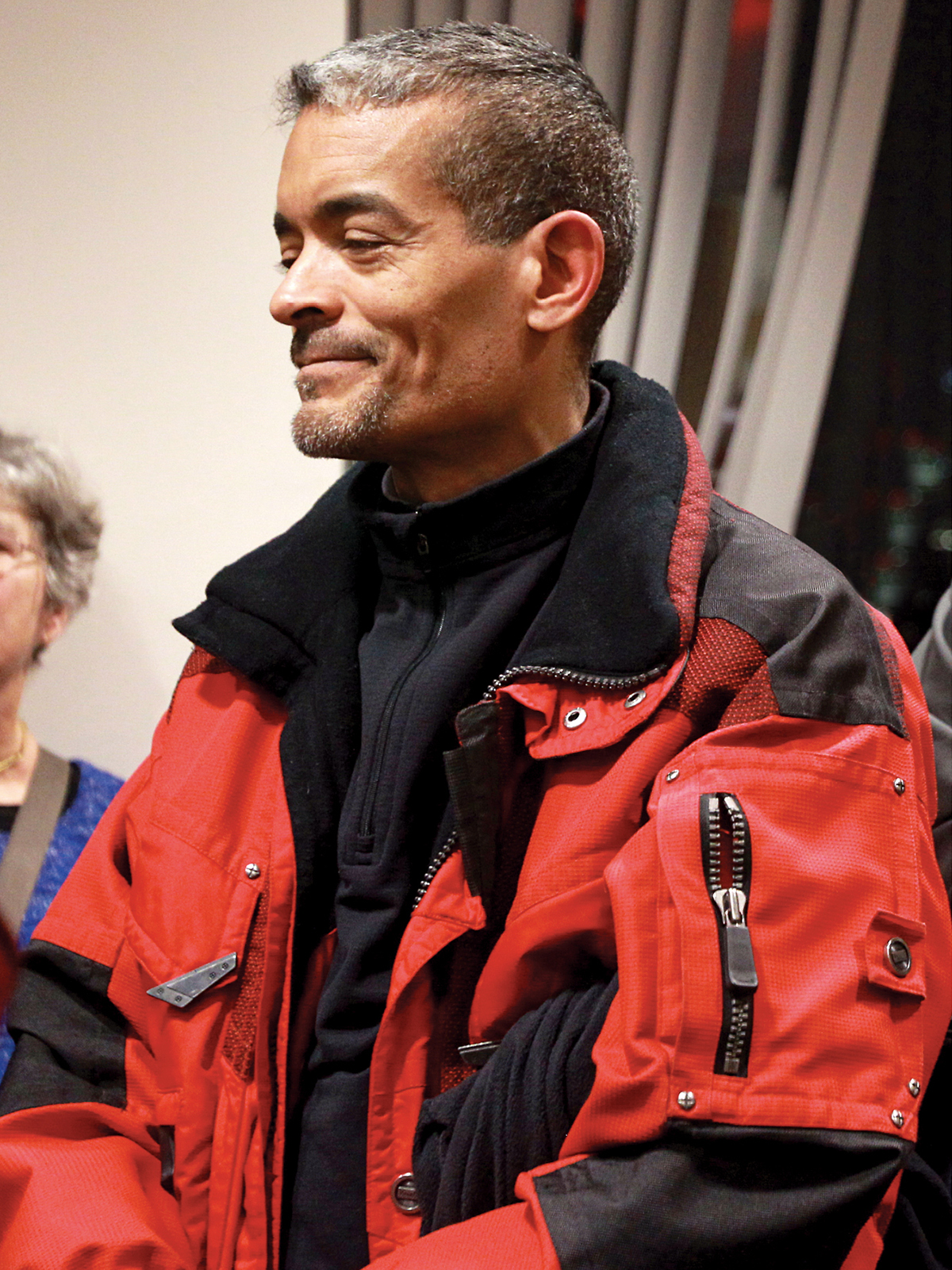

Police officer Prentice Pilot, who claims to have been the target of racism within the police department, waits for a board of selectmen’s meeting at Brookline Town Hall this past January. / Photograph by John Blanding/Boston Globe/Getty Images

On an unseasonably warm night a few days before Christmas last year, Brookline citizens toting “Black Lives Matter” signs packed into town hall ready to raise some righteous hell. One of the wealthiest municipalities in the state, Brookline is proudly among the most liberal towns in America—a place where residents are accustomed to making their voices heard before the town’s five selectmen, stewards of the left-leaning enclave. And on this night, the well-heeled rabble had good reason to be roused.

Prentice Pilot, one of a handful of black officers in the town’s police department, had accused a superior officer of slurring him—suggesting Pilot perform “nigger jumping jacks” in order to achieve a promotion. The department, Pilot said, was full of racism. He’d been known as an exemplary cop for 17 years, much of that time as a liaison to local public schools, and Pilot’s allegations tasted particularly bitter to a town and department that employ conspicuously few minorities in decision-making positions. No black supervisors have served in the police department in more than a decade, and Brookline has employed only two people of color as department heads in its history. Making matters worse for the town and its liberal reputation, Pilot’s claim followed a string of similar incidents: Another black policeman had come forward to describe ongoing racial abuse within the department, and a white firefighter had been promoted despite having left a racial slur on a black subordinate’s voice mail.

At town hall, instead of hearing out residents eager to discuss the allegations, the board of selectmen shut them down. The board’s chair, Neil Wishinsky, started off with a perfunctory statement and then refused to let his fellow citizens speak because they had not signed up beforehand, per town rules. “I’m not recognizing you!” he shouted at the crowd before leading his fellow selectmen out of the meeting. The town’s lone black selectman, Bernard Greene, didn’t think storming out of the meeting was a good idea but felt pressured to join. “As people started getting up,” he says, “I did not feel there was much of a choice.”

For Brookline, the episode was deeply off-brand. It is a regular competitor in magazine listicles of the best places to live in the nation, if you can afford the high real estate costs and cope with the community’s proud busybody nature. (It’s also been named at least once among the “snobbiest” towns in the country.) Democratic voters outnumbered Republicans by upward of five to one in the March presidential primary, and Brookline has consistently led the charge on progressive causes. Over the past 15 years, the town has banned plastic bags, Styrofoam, and trans fats; eschewed police stun guns; floated a tax on sport utility vehicles; debated the merits of the Pledge of Allegiance in schools; and even committed the sacrilege of dissing Dunkin’ Donuts when the chain wanted to set up shop along its suburban streets. Brookline, says town counsel Joslin Murphy, is a “beautiful oasis” in the Boston-area rat race, “a very educated town comprised of citizens who are deeply interested in social justice.”

An outspoken group of public servants and residents, however, say that such lofty ideals have little to do with actual town practices, and claim that racism within the police department is perennial and not simply isolated to one or two embarrassing and hateful incidents. As a result, Pilot and seven other police officers and firefighters have filed lawsuits in state and federal court alleging a “longstanding and well-established policy” of racial discrimination in the town. Many residents have spoken publicly or made court claims detailing their experiences with racial profiling and discrimination, and an April survey found that members of the town’s mostly white officer corps considered the department rife with nepotism. In January, the town’s own Commission for Diversity, Inclusion, and Community Relations declared that the board of selectmen was at fault for allowing “a culture of institutional racism” through its personnel decisions.

And yet Brookline administrators have been dismissive of the notion that the town has a racism problem that they have failed to address. Murphy, a former Brookline police officer, declares that the “town truly cares about these employees and very much hopes that they can return to work in a way that they are satisfied with.” But in nearly the same breath, she criticizes the attention that the employees’ discrimination claims have received, saying that their lawsuits are “weak” and that “when that’s the case, plaintiffs tend to lean toward public pressure.”

Pilot, who now chops trees in the Berkshires to make ends meet, is far less sanguine. “You can quote me on this,” he says. “I’m calling Brookline a fake-ass liberal town.”

Brookline wasn’t always a Xanadu for those who can afford an Aston Martin but prefer a Toyota Prius. Founded in 1705, it has a past—and a present—that suggest it has the same issues with bigotry and inequality as any other town in America, only perhaps a bit more subtly. That ugly history traces back to Brookline’s farming days. Residents owned slaves in Brookline through the late 18th century. The town still has a public elementary school named after Edward Devotion, a resident who willed a slave to the town upon his death.

Boston notoriously embodied the turmoil of the post–civil rights era—busing, riots, and racism. Brookline, on the other hand, doesn’t exactly spring to mind as a hotbed of racial injustice. Despite its reputation, though, discrimination was still pervasive. Scot Huggins, a black resident who has assisted in Pilot’s legal efforts against the town, moved to Brookline during the early 1970s, when he was five years old. He recalls that his school had a bathroom and a staircase that were known to be for whites only. Though it was an unofficial designation, it was enforced through violence, according to Huggins. Police, he says, harassed him “nearly every day.” He insists that “Brookline is a really great place. It’s just not as good for some as it is for others.”

Today, allegations of police profiling and harassment persist. Dwaign Tyndal, a member of the town’s diversity commission, relocated to Brookline 12 years ago for its excellent public schools and idyllic setting—that perfect little village nestled a short drive from downtown Boston. Yet, he says, conversations with other black Brookline residents inevitably circle back to how certain areas—such as Coolidge Corner—are notorious for traffic stops that reek of racial profiling. “Those are the areas,” Tyndal says, “where it gets communicated to you in different ways that you aren’t invited here.”

Arthur Conquest, a black man who has lived in Brookline for 34 years, agrees that if you’re black or Latino you should expect to be stopped by police when walking along the town’s streets. “All this business about the town being liberal, the town being progressive, and them being committed to diversity, it’s absolutely nonsense,” he says.

Proving racial bias in traffic stops is notoriously thorny, but statistics collected by the police department do show that black people make up a significant portion of those stopped in Brookline. In 2015, for example, Brookline officers performed 76 “field interrogations” of people who were stopped for what they deemed to be suspicious activity. In a town where roughly 3 percent of residents are black, 23 of those stops—or 30 percent—were of black people.

Brookline Police Chief Daniel O’Leary says his department has been among the state’s most proactive in tracking officers’ interactions, and that numbers related to race are often skewed by traffic stops of nonresidents. Even so, today’s police force hardly reflects Brookline’s liberal views. The department has not had a black officer in a supervisory role since a sergeant retired in 2004, and a recent town-commissioned study of the department’s racial climate reported that officers considered it an “Old Boy Irish Network” reliant on nepotism. “Being Irish helps,” one officer remarked of the department in that study.

For much of its history, Brookline consisted largely of Boston Brahmins and the Irish immigrants who staffed their homes. More recently a prominent Jewish population has taken hold. O’Leary, whose two brothers also served as Brookline police officers, says there is little his department can do to improve racial diversity in supervisory ranks because promotions are based on the results of civil service exams. The Irish-heavy makeup of the department dates back generations, to the days when O’Leary’s own ancestors were the oppressed servant class. O’Leary’s great-uncles, he says, had to drop the “O” at the beginning of their last names to find work. As the town became more affluent, fewer residents—outside of the descendants of other Brookline cops—were looking for jobs on the force, O’Leary explains. “It was gonna be blue-collar,” he says of the applicants to his department. “It was gonna be the Irish.”

The current inferno engulfing O’Leary’s police department and the town’s board of selectmen was actually sparked several years earlier in the fire department. In 2010, a black firefighter named Gerald Alston received a startling voice-mail message from his white supervisor, Lieutenant Paul Pender Jr., the son of a Brookline firefighter and boxer who has a town rotary named after him.

“Fucking nigger,” Pender could be heard saying before hanging up.