The World v. Alan Dershowitz

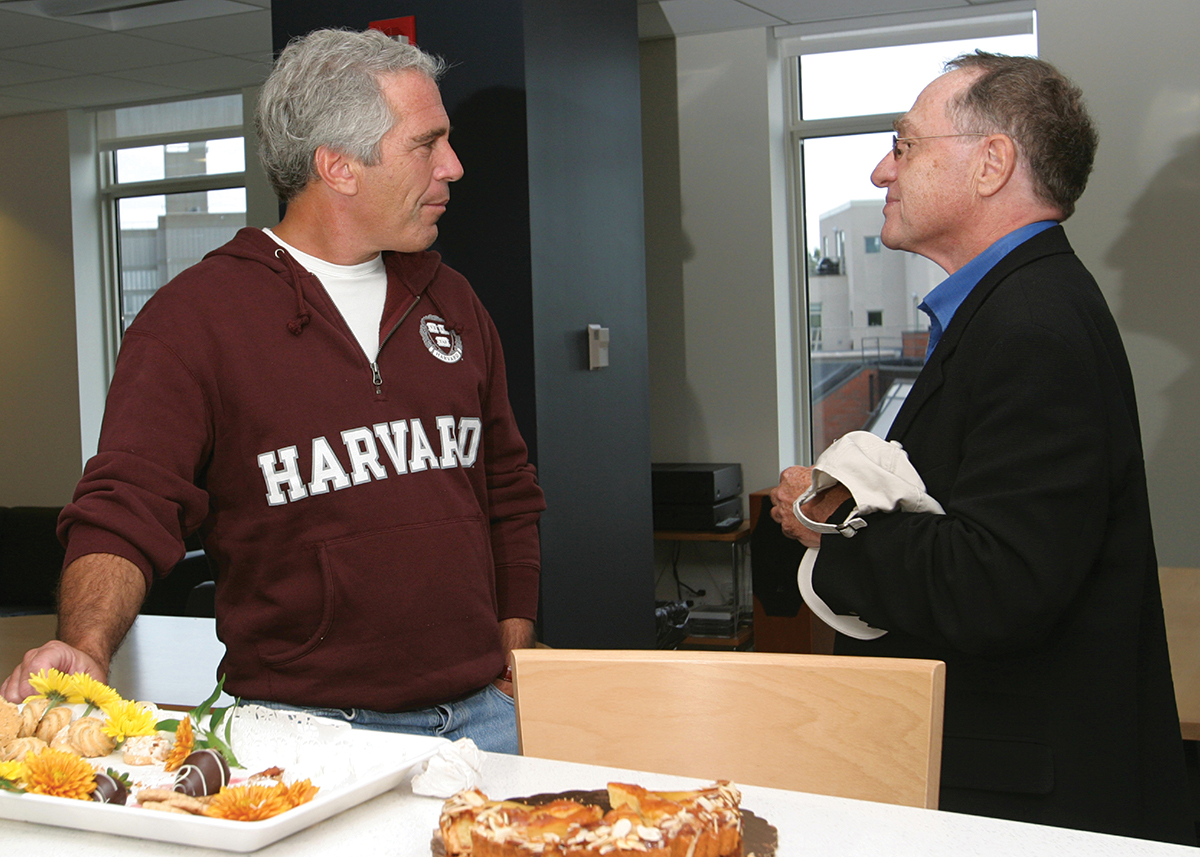

Financier Jeffrey Epstein and Alan Dershowitz met in 1996 through mutual friends from Martha’s Vineyard. / Photograph by Rick Friedman/Corbis/Getty Images

Behind the scenes, though, the Epstein drama played on. One by one, a number of the alleged victims reportedly reached out-of-court settlements with the billionaire. Then, in late 2014, a 31-year-old woman named Virginia Roberts sought to join two other women in a civil lawsuit alleging that federal prosecutors had violated the Crime Victims’ Rights Act by neglecting to consult victims about the cushy non-prosecution deal Epstein had struck.

By this time, it had been nearly a decade since the Epstein affair began and the national mood had shifted; allegations that would have once been ignored or uneasily tolerated now regularly incited outrage.

When she was 15, Roberts claimed, working as a locker-room attendant at Donald Trump’s Mar-a-Lago resort in Palm Beach, she became a traveling masseuse for Epstein. (Trump himself was sued for sexual assault in a separate Epstein-related case before the case was dropped.) Over the next three years, Roberts alleged, Epstein held her as his sexual captive. He would fly her to glamorous vacation spots—his private Boeing 727 was later dubbed the “Lolita Express”—and she would submit to his sexual whims.

Until that point, Dershowitz’s involvement had been that of Epstein’s attorney and friend. Suddenly, Roberts’s explosive filing stated that Epstein had offered her up to “prominent American politicians, powerful business executives, foreign presidents, a well-known Prime Minister, and other world leaders.” But she listed only four people by name: Prince Andrew, the Duke of York; British socialite Ghislaine Maxwell; modeling executive Jean Luc Brunel; and Dershowitz. (All four have denied Roberts’s claims.) In her sworn affidavit, Roberts claimed to have had sex with Dershowitz on numerous occasions, at several of Epstein’s residencies and his jet, while she was a minor. (Dershowitz is married and has three adult children. Carolyn Cohen, his second wife, is a psychologist.)

Shortly after 7 a.m. on January 5, Dershowitz appeared live on NBC’s Today show from his winter home in Miami Beach and promptly blew his top. “I have never seen her,” he told Matt Lauer. “I’ve never met her. I don’t even know who she is. And her lawyers have to know this.” An hour later, he was on CNN. “The real villains,” he said, were her attorneys—Bradley Edwards, a Florida lawyer, and Paul Cassell, a former Utah federal judge, both of whom specialize in victims’ rights cases. Over the course of his career, Dershowitz has repeated a maxim that rape is both the most underreported and overreported serious crime in America. But false accusations, he has argued, are the greater evil, for they cheapen the cause of legitimate victims. “I am seeking their disbarment,” Dershowitz added, “and that’s what ought to happen to them.”

The day after Dershowitz’s television appearances, Cassell and Edwards responded by filing a defamation lawsuit. Dershowitz countersued, and began mobilizing to discredit the allegations against him: Thirty-seven Harvard law professors signed a letter vouching for his good character. He hired former FBI director Louis Freeh to conduct a forensic audit of his travel and cell-phone records. Meanwhile, Roberts was increasing her own legal firepower: Powerhouse DC litigator David Boies—of Bush v. Gore and U.S. v. Microsoft fame—signed on to represent her in a related case.

The feud kept escalating. During an October 2015 court deposition, Dershowitz claimed he had not only been wrongly accused but also intentionally framed. Citing information he received from a woman who said she was a close friend of Roberts, he accused Edwards and Cassell of pressuring their client to name him in order to then use him as a pawn in a broader extortion plot aimed at another one of Epstein’s powerful friends, Leslie Wexner. Cassell, Edwards, and Boies fired back to me in a statement that “there is not and never has been any ‘billion dollar extortion plot’ or for that matter any extortion plot of any kind directed at Leslie Wexner or anyone else,” adding that “no attorney pressured” Roberts into lodging her accusation against Dershowitz. (An attorney for Wexner did not respond to requests for comment.)

Those who are close with Dershowitz say the accusation against him doesn’t jibe with his personality. “Knowing Alan, knowing his wife, knowing his family—it never added up to me,” Susan Estrich says. “Some guys like to operate that way. I’ve never seen him operate in that kind of way.” Indeed, the image of bookish Alan Dershowitz taking part in Dionysian underage massage sessions at 30,000 feet doesn’t totally compute. “As I said to my wife,” Dershowitz tells me, channeling his inner Alvy Singer, “I never had sex with an underage girl even when I was an underage boy!”

After more than a year in court, the dueling defamation lawsuits were laid to rest and the two sides settled. Though Roberts told the court she reaffirmed her accusations against Dershowitz, her lawyers formally withdrew them. Louis Freeh said his investigation pointed toward Dershowitz’s innocence. The two sides pledged to a mutual nonaggression pact and seemed to put the matter behind them.

Yet Dershowitz doesn’t feel vindicated. He’s advocating for legislation that would prevent lawyers from accusing nonparties (such as himself) in court, and may write a book about his experience. With the legal battle over, though, even higher stakes have come into focus: half a century of hard-won success and reputational glory. “It can’t be an accident,” he says, “that suddenly—I used to get requests for honorary degrees every year—I’ve gotten none since this happened, because nobody wants controversy. I’ve lost at least two clients, both of whom said they were sure I was innocent, but didn’t want the ‘baggage.’” When I ask him how he thinks his obituary will read, the first thing he says is, “Well, unfortunately, it will include this allegation, which makes me furious.” Later, in horror, he imagines his name being lumped with that of another infamous accusee. “This is not Bill Cosby,” he says. “I have led an absolutely exemplary life.”

Underlying recent accusations against Cosby—or Roger Ailes, or Donald Trump, for that matter—is an environment that has made it less daunting for victims of sexual abuse to lodge claims against the powerful. More broadly, what some deride as PC culture, others view as the welcome destabilization of a largely white, largely male power structure. When Trump criticizes political correctness, he is channeling resentment toward the (nonwhite, nonmale) demographic groups who tend to benefit from it. In this way, Dershowitz has much to fear from the new norms of the progressive left. Whether or not Roberts’s accusations had merit, they materialized out of a societal role reversal—at least in certain quarters—in which the distinguished law professor emeritus is no longer given the benefit of any doubt.

Last fall, Dershowitz was invited to Johns Hopkins University to participate in a public discussion about the Arab-Israeli conflict. There, he was protested both by Students for Justice in Palestine and by Hopkins Feminists, whose members wore duct tape over their mouths and held signs that read, “You Are Rape Culture.” (The Sexual Assault Resource Unit, the Diverse Sexuality and Gender Alliance, the Black Student Union, and Voice for Choice merely petitioned against his presence on campus ahead of time.) Dershowitz has griped about the “intersectional” politics of the campus left. Here he was in its crosshairs. “When the [Epstein] accusations first came out, the first people who came after me were…the anti-Israel people,” Dershowitz says. “‘Oh, what Dershowitz did to young girls is what the Israelis are doing to the Palestinians.’”

On the contrary, Dershowitz says. “I’m a victim. That’s why I’m speaking out. I’m a victim.”

In early October, I drive to pick up Dershowitz at his apartment a few blocks south of the Queensboro Bridge. Our plan is to scoot across the East River and visit his childhood digs in the ultra-Orthodox Jewish enclave of Borough Park, Brooklyn. As he ducks into the passenger seat, Dershowitz begins fumbling apologetically with a tape recorder. At the behest of his lawyers, he has insisted on taping our conversations. “These guys are looking for an opportunity to sue me at any time,” he explains, both of our recording devices now turned on. “All you have to do is misunderstand one thing I say, and it could be a lawsuit.”

We get to Borough Park the day after Rosh Hashanah has ended. Per custom, Dershowitz greets passersby with a friendly “Shanah Tova.” Hasidic Jews, generally being indifferent to non-Hasidim, stare blankly and say nothing. He says, “It’s a very vibrant community. Good food, good Jewish food. It’s completely Hasidic in the sense that if I walk down the street in Manhattan, people stop me all the time. Oh, we know you. Here nobody knows me, because they don’t watch TV and they don’t read secular newspapers.” He considers this. “Some of them do know me. Because I’m on YouTube. And they can do YouTube.”

Dershowitz’s mother used to worry that her son’s success would be short-lived, that he would find himself banished back to the provinces. “She calls and pleads with me to stop already, to be friends with those in authority,” Dershowitz told a reporter more than 30 years ago. “She’s always talking about the ‘house of cards’ I’ve built for myself, how somebody will topple it by removing the bottom card…but I live in the United States of America. The worst thing that happens here is that people say nasty things about you.”

Now, even that has become too much to bear. With his tape recorder whirring, Dershowitz can’t help but launch into yet another attack against Edwards and Cassell, dredging up a case that was settled months ago. “The lawyers who filed this against me have real, real problems,” Dershowitz says, later adding, “I think Cassell is a zealot. I think he honestly believes that women who claim to have been raped would never in any circumstance lie. And Edwards is an opportunist.” After fretting that he would be sued once again for defamation, Dershowitz attempted to retract many of his most explosive allegations. Then, several days later, he called me and repeated them all over again.

Even if Dershowitz escapes another lawsuit, the imbroglio feels like a self-inflicted wound. “If Alan has any flaw, it is that he is sometimes too sensitive to what people are saying about him,” Harvey Silverglate says. “Alan has a lifelong history of going into overdrive for lesser accusations. I understood it, but I wish I could have talked him into being more calm.” More than one person I spoke to compared Dershowitz’s thin skin to that of a certain president-elect. “He has an unparalleled career,” Silverglate has said, “and somehow has the feeling he’s going to wake up one morning and find out it’s all gone, it was a dream.”

And so he’ll write Electile Dysfunction and he’ll trudge to Newsmax, unaware that he has nothing left to prove. So when he’s cast—by Roberts, or by campus protesters—as a member of the oppressor class, it seems to bewilder him. “As somebody who grew up in a poor Jewish background,” he says, “where we knew there were quotas to get into college, and knew we couldn’t get jobs at certain law firms, the idea that we’re ‘privileged,’ or that our children and grandchildren are ‘privileged,’ comes as something of a shock.”

Before I drive him back to his apartment, Dershowitz loans me a 1,039-page issue of the Albany Law Review devoted entirely to “Honoring the Scholarship and Work of Alan M. Dershowitz” and implores me to read it. Then, from the defense, one final appeal: “This is for you, another article. You’ll write a lot of articles. Some will be better, some will be worse. For me, what you say could have a major impact on my life. I’m just urging you, please be fair, please be careful.” He pleads: “It’s much more important for me than it is to you.”

Simon van Zuylen-Wood is a contributing editor at Boston magazine. He also wrote “The Ballad of Buddy Cianci” and “Nothing to Lose: Bill Weld’s Last Hurrah.”