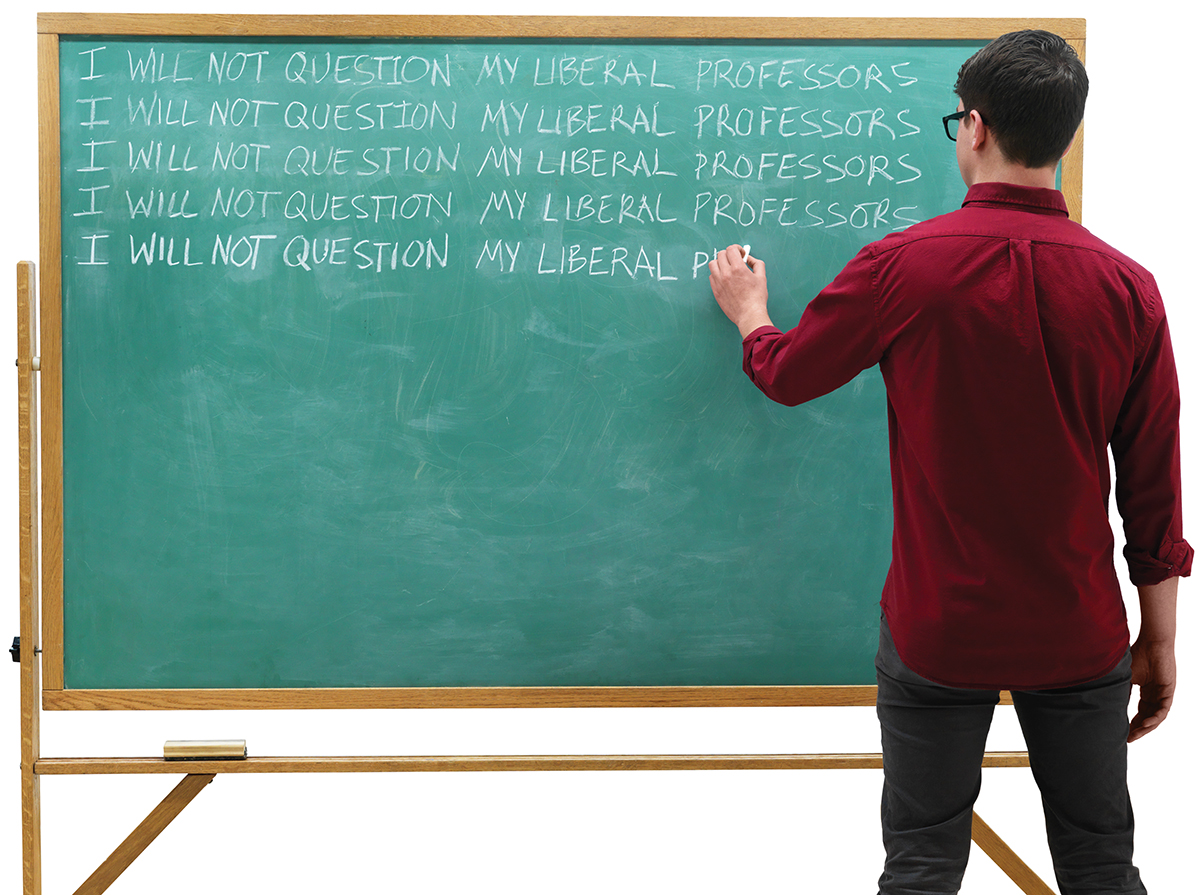

How Liberal Professors Are Ruining College

In New England, they outnumber conservatives 28 to 1. Why that’s bad for everyone.

Photograph by Bruce Peterson

The freshman had his hesitations. “I am somewhat ‘in the closet,’” he emailed me from the safety of his dorm room. It was near midnight on a Thursday in late October, and the young man was still adjusting to life at Brandeis University. While he was open to the idea of doing an interview, he worried about the consequences of revealing his true self. “I fear that many of my classmates would jump to conclusions about me,” he wrote, “should they all know I am a conservative.”

To be clear: This student, whom I’ll call Ben, is not an alt-right provocateur railing against multiculturalism or a bombastic neocon. He is a skinny, stressed-out, 19-year-old Jewish kid from New Jersey who bounces his leg when he talks and prefers the Wall Street Journal to Breitbart. As with so many college students, he’s wrestling with his political identity and trying to figure out where he stands on some of the biggest issues of today, from the humanitarian crisis in Syria to police violence in America. Exploring his conservative viewpoints, though, is proving difficult to do on campus: There’s the econ professor who cracks jokes about Republicans during lectures, Ben says, not to mention the orientation event during which the speaker understandably talked passionately about the importance of Black Lives Matter, but glossed over the social movement’s assertion that Israel is an apartheid state that engages in genocide—a particularly thorny issue at a school where the undergraduate population is, according to Hillel, 47 percent Jewish.

All of this makes Ben feel like an outsider. The way he sees it, coming out politically a step to the right is the fastest route to social isolation on campus and the surest way to invite ridicule from his professors. So he bites his tongue in class and retreats to his dorm room to read and listen to conservative commentary alone. “I think it’s a shame,” he tells me. “A lot of people have negative preconceived notions about conservatives…we’re intolerant, racist, homophobic.”

The definition of conservatism has never been more muddy—depending on who you ask, it can range from white nationalists espousing hate to moderates such as Governor Charlie Baker. At many of New England’s most prestigious colleges, political conservatism has been reduced to stereotypes, conflated with the alt-right and branded as being so wrongheaded that it’s not even worth considering, let alone hiring professors who embrace right-leaning ideas. Long known as bastions of progressive thought, and home to the likes of Noam Chomsky and the late Howard Zinn, our region’s schools have always been suspected of putting the “liberal” in liberal arts college. Until recently, though, no one had quantified just how far left higher ed here had drifted.

Last spring, Samuel Abrams, a professor of politics at Sarah Lawrence College, in New York, decided to run the numbers. From the start, he certainly expected liberal professors to outnumber conservatives, but his data—25 years’ worth of statistics from the Higher Education Research Institute—told a far more startling tale: In the South and throughout the Great Plains, the ratio of liberal to conservative professors hovered around 3 to 1. On the liberal left coast, the ratio was 6 to 1. And then there was New England—which looked like William F. Buckley’s worst nightmare—standing at 28 to 1. “It astonished me,” says Abrams, whose research revealed that conservative professors weren’t just rare; they were being pushed to the edge of extinction.

This phenomenon has been quietly unfolding for years. Abrams, who describes himself as a centrist and earned a doctorate from Harvard, sees the decline as a canary in the higher education coal mine, undercutting the mission of college and diminishing the value of six-figure educations. When the student and teacher activists of the 1960s marched across many of these same leafy campuses, they were often fighting for freedom of expression. After all, isn’t that what being a social progressive is all about? Today’s movements, on the other hand, are widely aimed at preventing the established power structure from harming less-privileged groups. Consequently, student activists have banded together—sometimes alongside faculty—in support of safe spaces, protective speech, and trigger warnings. It is the best way, the thinking goes, to align with and support all identity groups. To some people on the receiving end, however, progressive rhetoric can sound shrill and an awful lot like suppression of speech and intolerant political correctness. The result? Many conservatives on New England’s campuses are feeling more marginalized and alienated than ever before.

If you believe that plurality, open discourse, and exposure to conflicting lines of thought are critical to a complete education and to a fuller understanding of how the world works, this relatively recent shift should set off alarm bells. It certainly did for University of Chicago dean of students John “Jay” Ellison, who penned a letter notifying incoming students that “freedom of inquiry and expression” will not give way to so-called trigger warnings or safe spaces “where individuals can retreat from ideas and perspectives at odds with their own.” After all, the more viewpoints we are exposed to, the better equipped we are to understand one another so we can make decisions together. “Creative problem-solving is going to suffer,” Abrams says, arguing that ideological homogeneity does not prepare students for life after graduation. “The goal of college is to give you multiple viewpoints and to grow your mind, not to just be comfortable in your own bubble. The real world is not full of progressives.”

At a time when Donald Trump is setting up camp inside the West Wing, our ivy-gilded campuses in the foothills of Vermont and the suburbs of Boston are emerging as some of the most contentious ideological beachheads in the country. In response to Trump’s ascendance, campus politics are primed to swing even more to the left, potentially further alienating those college conservatives who are confounded by Trump and trying to find their political selves in today’s climate. These are the same students who may be susceptible to right-wing radicalization if we allow one of the most important forums for debate and intellectual exploration to devolve into just another partisan war zone. “New England’s college campuses,” Abrams warns, “are a powder keg ready to blow.”

Conservative professors weren’t always so heavily outnumbered here. In 1989, according to Abrams’s data, the ratio of liberal to conservative professors in New England was 5 to 1. The divide widened slowly through the 1990s and then tore open shortly after the turn of the century. Then, between 2004 and 2014, conservative professors essentially fell off the face of the Northeast.

At first, even Abrams had a hard time believing the 28-to-1 ratio was accurate. He checked and rechecked his work, accounting for every variable he could think of—tenured versus untenured professors, age, income, type of college, the selectivity of the college, which departments the professors belonged to. Time and again, though, the results showed that geography was among the strongest determining factors when it came to the political diversity of professors. After Abrams took his findings public in the New York Times, academics were floored. “That number, 28 to 1, does give one pause in thinking about what ideological diversity is and what an institution’s responsibilities are in thinking about it,” says Isabel Roche, provost and dean of Bennington College, in Vermont. “It’s a really important educational question.”