GE CEO Jeff Immelt Is All In

In more than a few ways, Immelt is a magazine writer’s nightmare. He’s an earnest, midwestern Protestant who’s been happily married to the same woman since 1986. His politics are sensible and center-right. He has been praised as dispassionate. His famously abrasive predecessor, “Neutron Jack” Welch, once said of Immelt, “At times, I might get too emotional. He doesn’t.” Immelt is competitive, but not too competitive. “It’s in a good way,” his brother, Steve, says. His friends say he likes to talk shit on the golf course, but assure me there’s never any swearing. Trash talk, for Immelt, means gentle goading about putts. In the public sphere, the spiciest thing he’s done in years is call out Bernie Sanders for claiming, as only Sanders could, that GE was “destroying the moral fabric” of America. (The political left criticizes Immelt for his company’s aggressive negotiating with labor unions and infamous tax-minimization shenanigans.) “We’ve never been a big hit with socialists,” Immelt retorted in a Washington Post op-ed. “We create wealth and jobs, instead of just calling for them in speeches.”

Whether he knew it or not, Sanders had provoked Immelt in just about the only way possible: by impugning the integrity of his beloved GE. If nothing else, Immelt is a true GE homer. “I love this company,” he’s professed numerous times. When I asked why, he said, “Oh gosh, I have a different context than most people.” His father, Immelt explains, worked in GE’s aircraft engine division near Cincinnati for 38 years. Immelt, for his part, has never seriously considered pursuing a career anywhere else. At Harvard Business School, where he studied after his undergraduate years at Dartmouth, his ambition to climb the ranks at GE was common knowledge. “In our second year of business school,” says Steve Mandel, a former roommate whose wife, Susan, was a classmate, “my wife made a bet that Jeff would eventually run GE.”

Immelt joined GE straight out of HBS and came face to face with the company’s astounding breadth. His early jobs forced him to learn the finer points of refrigerator compressors and raw plastics. In 1997, when Immelt was promoted to run GE Medical Systems, a high-tech unit that manufactured CT and MRI scanners, he found a business he loved. In the three years he led the division, he grew sales by 75 percent, increased market share, and turned around the flagging European market. His performance ultimately won him the confidence of Welch, who handpicked Immelt as his successor in 2000. The following year, Immelt, then 45, took the reins of the world’s biggest company.

Reflecting on his rise, Immelt says, “So much of it is luck.” Still, he had become a highly confident leader. He recalls a lunch in the 1990s with Welch and other CEOs. “I remember thinking, I may not be as good as he is,” Immelt says, referring to Welch, “but I’m as good as any of these guys.” Now with Welch’s endorsement and buoyed by his success at Medical Systems, Immelt entered the top spot with an ambitious plan that would lay the foundation for today’s transformation. “Even before I became CEO,” he tells me, “the vision I had for GE was that we needed to restore the technical foundation of the company.” Translated, that meant investing in high-tech innovation and focusing the company on making big, complex machines such as medical scanners and jet engines. At the same time, this long view set him on a crash course with Wall Street investors more concerned with the next quarter’s profits.

Immelt’s long-range plans, though, soon had to take a back seat. The September 11 attacks, which occurred on Immelt’s fifth day as CEO, ushered in a period of sustained crisis for the company, including the 2008 financial disaster that nearly bankrupted GE’s $661 billion finance division, called GE Capital. “You’ll never in your lifetime go through something quite that intense,” he tells me. In fact, he once described 2008 and 2009 as the “toughest years of [his] life.” As the global financial system teetered on the brink of collapse, he had a private ritual that helped him project an air of calm to his employees and the public. “You tend to be your own worst critic,” he says. So every night he went to bed feeling like a failure. “But in the morning, you’re reborn.” In front of the bathroom mirror every day, he would say to himself, “Hello, handsome” and start over.

During these years, Immelt earned a reputation as a steady navigator, yet GE’s performance lagged. Even as the stock market rocketed upward after 2009, the company never returned to its pre-crisis heights. Investors blamed Immelt, and beginning in 2014, the knives came out. That fall, Scott Davis, an influential Wall Street analyst, called for a “full AT & T–style breakup” of GE. A few months later, he went even further, suggesting that Immelt could be replaced as CEO within a year. “[M]ost investors are ready for change at the top now,” he wrote. Others ditched the stock altogether. “GE has not been well managed at all,” one prominent money manager said after abandoning his GE position. Taking stock of Immelt’s tenure, Davis wrote that he “knows that he doesn’t have a ton of time to repair his legacy.”

What Wall Street didn’t yet know was that Immelt, after years of putting out fires, had finally set in motion the key components of his plan to overhaul GE. On April 10, 2015, surrounded by his top executives, Immelt sat down in a windowless conference room in Fairfield for an early-morning phone call. On the other end of the line were a dozen analysts, many of them deeply skeptical of Immelt’s leadership. In a jargon-laden monologue, Immelt told them that, beginning immediately, GE would sell almost all of GE Capital, accelerate its transformation into a high-tech infrastructure company, and double down on becoming a software giant. For Immelt, this was a watershed moment. GE Capital had grown to ridiculous proportions. “Being 50 to 55 percent of [GE’s total] earnings,” Immelt says, “that wasn’t where we wanted to be.” Selling it would free him to invest in GE’s industrial businesses and would streamline the company along the lines of the bold “breakup” Davis had called for.

The analysts were almost giddy. “Congrats. This is big stuff,” Davis told Immelt. “I know we’ve all given you a lot of crap over the years, but this is pretty good stuff for redemption.” He added: “You can keep your job a little longer, I guess.” Immelt and his coterie laughed—perhaps a bit too effusively. After all, the rumors of his undoing hadn’t been a joke.

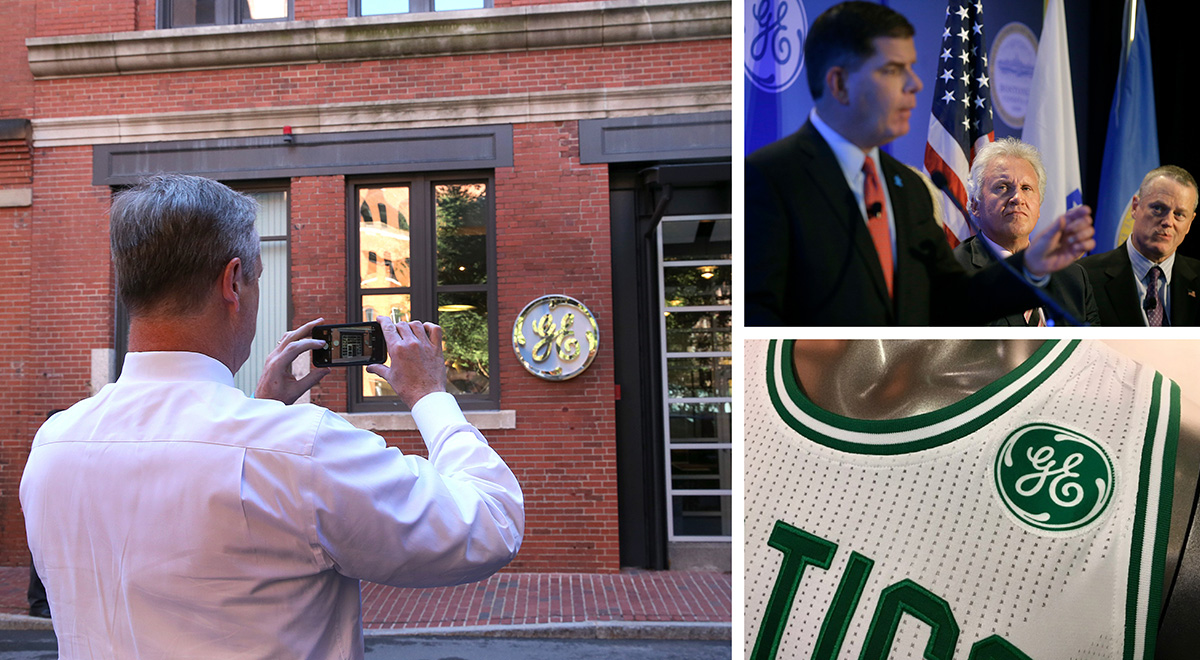

Governor Charlie Baker snaps a photo of GE’s headquarters; Mayor Marty Walsh announces the big move; the Celtics jersey will get a fresh logo next season. / Photographs by David L. Ryan/Boston Globe/Getty Images (Baker), Steven Senne/AP Images (Walsh), Kyle S. Clauss (jersey)

“I want some 29-year-old Ph.D. student at MIT to punch me right in the nose and say, ‘All of GE’s technologies are wrong and you’re about to lose,’” Immelt said. Holding forth inside the Boston Harbor Hotel ballroom, he sat grinning, waving his huge hands, and chuckling along with the crowd. Intentionally or not, his down-home, self-deprecating shtick was having the ideal effect. The gray-haired business leaders arrayed before him—including Robert Kraft and the bosses of Wayfair and Raytheon—were eating up his jokes.

Immelt was there to announce the site of GE’s new headquarters—a 2.4-acre plot on the banks of the Fort Point Channel—and to explain why his company, which he has taken to calling a “digital industrial,” was coming to Boston. “I want [GE employees] that are down in the Seaport…to walk out of their office every day and be terrified,” Immelt said. “I want them to be completely paranoid. Are we moving fast enough? What can we do better? Who’s smarter than we are? I want to be in this sea of ideas so that paranoia reigns supreme inside the company.”

Since arriving in Boston last August, Immelt has pushed his employees to engage with the city’s tech community. Investors from GE Ventures, the company’s venture capital arm, meet with startup founders at District Hall, in the Seaport. GE managers attend Industrial Internet brainstorming sessions at the offices of Rethink Robotics, a Seaport neighbor. GE will also literally open its doors to techies, with a coworking space inside its headquarters, once its 12-story Seaport fortress is built. (Groundbreaking is scheduled for May 8 and the opening for some time in 2019.) So far, the Boston business community has welcomed GE’s efforts with unbridled exuberance. “Boston is so lucky to have a large, thoughtful, successful corporation move here,” Maia Heymann, the tech venture capitalist, gushes.

Until recently, though, “digital industrial” was not a recognized species of business. There were digital companies, like Microsoft, and there were industrials, like GE and Siemens. But there were no true hybrids. Nevertheless, Immelt believes that to survive in the 21st century, GE has to become one.

During his first 14 years as CEO, Immelt had focused on the “industrial” part of the transformation. “We started right away,” he tells me. Even as he dealt with the financial consequences of 9/11 and the recession that followed, he increased the budgets of GE’s research labs and bought healthcare technology startups. Later he sold off extraneous businesses such as GE’s insurance operations, NBCUniversal, and GE Appliances. Finally, after the financial crisis, he poured billions into GE’s power plant and oil and gas businesses.

Next came the “digital” phase: creating the software that would connect industrial machines to each other, and to the cloud. This nascent technology is called the Industrial Internet—essentially the Internet of Things for big machines and infrastructure. Immelt believes it is the next revolution in computing—a technology sector with the potential to boom in much the same way the consumer Internet has over the past 15 years. “The wave has taken off,” Immelt tells me, “and our customers are grabbing it.”

How big is the potential opportunity for GE? “Oh, it’s completely insane,” says Isaac Brown, an Industrial Internet expert with Landmark Ventures. “Every factory, every oil rig, every power line, every farm, every tractor.” They can all be connected. Immelt estimates the potential size of the market is $100 billion a year. “Look, this is big,” he says bluntly. “Really big.” Immelt’s GE is poised to capitalize—if it can innovate quickly enough. But big corporations usually aren’t good at leading the charge into new technologies. In fact, their track record is terrible.

The most famous failure may be IBM’s. In 1980, it had created the first personal computer for mass-market distribution. But in a crucial blunder, IBM paid a startup called Microsoft to provide the operating system—the software that made the computer run—rather than developing the software itself. The operating system, MS-DOS, was a precursor to Windows and turned out to be the more valuable part of the business. Even though IBM had been perfectly positioned to dominate the market, it missed out—and Bill Gates became the richest man in the world.