Chasing the Midnight Ghost

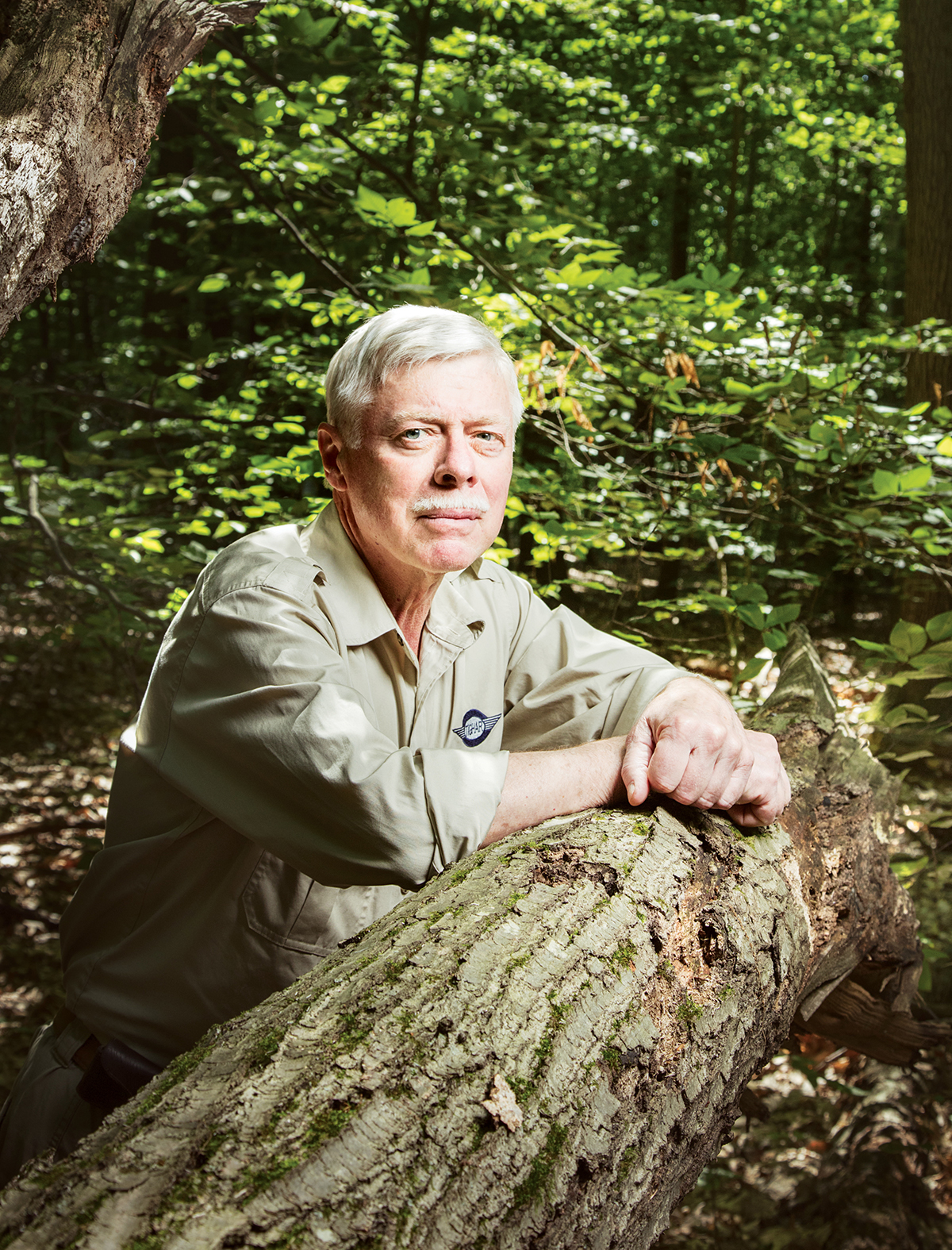

Airplane archeologist Ric Gillespie has been searching for the downed aircraft on and off for more than three decades. / Portrait by Ryan Donnell

In 1980, Ric Gillespie was opening the mail at his home in Pennsylvania when he spotted a letter from his younger brother, Bob, containing an article from Yankee magazine. The story told of a hermit who’d heard a plane crash in the hills of eastern Maine on the day the White Bird went missing. The article was extensive and it included a map. Fascinated that a famous missing plane was buried in the forest somewhere, Gillespie carefully placed the magazine clipping in a drawer for safekeeping.

If anyone was destined to search for missing airplanes, it was Gillespie. Raised in upstate New York, the eldest son of a decorated World War II pilot, he’s been consumed by aviation for as long as he can remember. He learned to fly around the same time he learned to drive a car, and he worked his way through college, where he majored in history, piloting charter planes. After completing a brief stint in the Army, he took a job in aviation insurance that allowed him to fly in and out of small airports all along the East Coast. Gillespie sold policies, but he also performed risk assessments and accident investigations. That was the part of the job he liked best: He had an eye for looking at the scene of a crash, examining all of the known evidence, and piecing together the puzzle of what had happened. “Aviation accidents were taking people away from the people they loved,” he tells me. “It was traumatic. I said to myself, ‘I want to help keep this kind of thing from happening. This kind of thing should be preventable.’”

Still, the longer he worked in insurance, the more time his managers expected him to sit in an office and stare at spreadsheets. Throw in an unpleasant divorce from his wife, and Gillespie was ready for a change. He’d always remembered the Yankee article and knew that if he could apply his accident-investigation skills and find the White Bird, it would change his life forever.

A veteran pilot with ruddy cheeks and a finely trimmed mustache, Gillespie’s first step was comparing maps of Maine to the one in the magazine article. He recognized that at this point, the only thing left of the plane, which was made mostly of wood and cloth, would be some wires and the engine. He also knew there were stories that had been passed down, like folklore, of hunters seeing an engine in the woods near Round Lake.

After researching the mysterious case, Gillespie theorized that Nungesser and Coli likely made it all the way to Maine, where they faced stronger headwinds than they’d expected. Perhaps the pilots tried to find another route around the icy weather and ran out of fuel where Anson Berry heard the crash. It was possible, Gillespie thought, that a hunter or woodsman could have stumbled upon the wreckage and, having no idea it was part of a famous missing plane, scavenged for anything valuable and left or buried the rest. Gillespie decided to go to Maine and look for himself.

In the summer of 1984, he called up his brother and asked if he might want to spend a weekend in Maine looking for an old plane. They had a fun trip, talking with locals and playing Indiana Jones in the woods, but they didn’t find anything.

It was around that time, though, that Gillespie met his second wife, Pat Thrasher. “She was crazy enough to find all this stuff as interesting as I did,” he says. Together, they quit their jobs and dedicated their lives to finding missing planes. In January 1985, the couple founded the International Group for Historic Aircraft Recovery (TIGHAR).

Over the years, Gillespie has examined historical crash sites around the world, worked with the U.S. government to reinvestigate decades-old incidents, and appeared on countless television shows and documentaries. Gillespie also wrote a history book about the Amelia Earhart mystery, and he has a convincing theory about what may have happened.

Earhart’s story tends to get more attention, Gillespie says, because Americans learn about it in elementary school. Conversely, he believes, the White Bird is more important. If the plane had landed ahead of Lindbergh, he says, it might have sparked an alternative history: Imagine, for instance, if the French—and not the Americans—had been inspired by their hometown heroes and taken the aviation industry by storm?

For generations, Mainers have earned a reputation as rugged and self-reliant, and along with that comes a healthy distrust of outsiders. Gillespie certainly didn’t expect many people would talk to him when he first started hunting the White Bird. He was, in the parlance of the locals, “from away.” Much to his delight, though, nearly everyone he met was willing to open up. Gillespie sat down with Harold Vining, the blueberry farmer who’d heard plane noises that fateful day in May 1927. He talked to acquaintances and relatives of Anson Berry, the reclusive woodsman who said he’d heard the crash. He even talked to hunters who said they’d seen the wreckage over the years.

The plane’s precise whereabouts have never been known. When it first disappeared, experts assumed it had plunged into the roiling swells of the Atlantic. The French, United States, and Royal Canadian navies launched a massive sea search along the planned flight route but came up empty. Eventually, though, reports began to surface of people in both Maine and southeastern Canada who saw or heard a plane on May 9, the day Nungesser and Coli would have been flying overhead. Gillespie believes the chances are “100 percent” that the French pilots made landfall. “It’s just a matter of where they decided to land,” he says.

Gillespie and his wife made expedition after expedition through the Maine woods, thrashing the thickets with machetes, walking the old logging trails with metal detectors, and making camp in the dense brush. One summer, they teamed up with the author of the Yankee magazine story, a 6-foot-4 actor turned writer named Gunnar Hansen, who played Leatherface in the original The Texas Chain Saw Massacre. Together, they borrowed planes and helicopters to search the steep hillsides and valleys near Round Lake. At various points throughout the mid-1980s, Gillespie attracted dozens of volunteers from across the country to join his search. The fact that none of the hunters who said they’d seen wreckage were able to find it again was frustrating, but the stories—and the tantalizing possibility of discovery—pushed them forward.

In the fall of 1987, Gillespie finally had exciting news. He staged a press conference and announced that his team had discovered a narrow piece of wood that may have belonged to the White Bird. It was broken into different segments that, when pieced together, amounted to the approximate width of one of the plane’s wings. Botanists and archeological experts had verified that the stick wouldn’t have grown naturally in Maine, Gillespie explained, and that it may not have even come from North America. Tree rings in the area also indicated that there may have been a fire there years earlier—the type you might see at the site of a plane crash. “We are not trying to convince anyone that we have found the White Bird,” Gillespie told reporters, “but we suspect we know where it is.”

In a small town an hour outside of Philadelphia, not far from the Delaware state line, Gillespie and Thrasher’s 200-year-old house is overflowing with boxes and historical files. On the wall near the back door is a framed sketch of the White Bird. Behind the bar is a painted wooden model Gillespie made a few years ago. Many of their neighbors are Amish and have never been on a plane.

In eight full years, Gillespie and Thrasher made 20 trips to Maine, each time testing a different theory or searching a new hill or bog. Yet aside from the mysterious stick and questionable tree rings, they have never found anything that could pass as evidence of the plane. “We finally realized that all there was in Maine was stories,” Gillespie has said. “People in Maine love stories. They’re very good at telling stories and those stories always get better each time they’re told.” His organization, he says, “has to follow the evidence.”