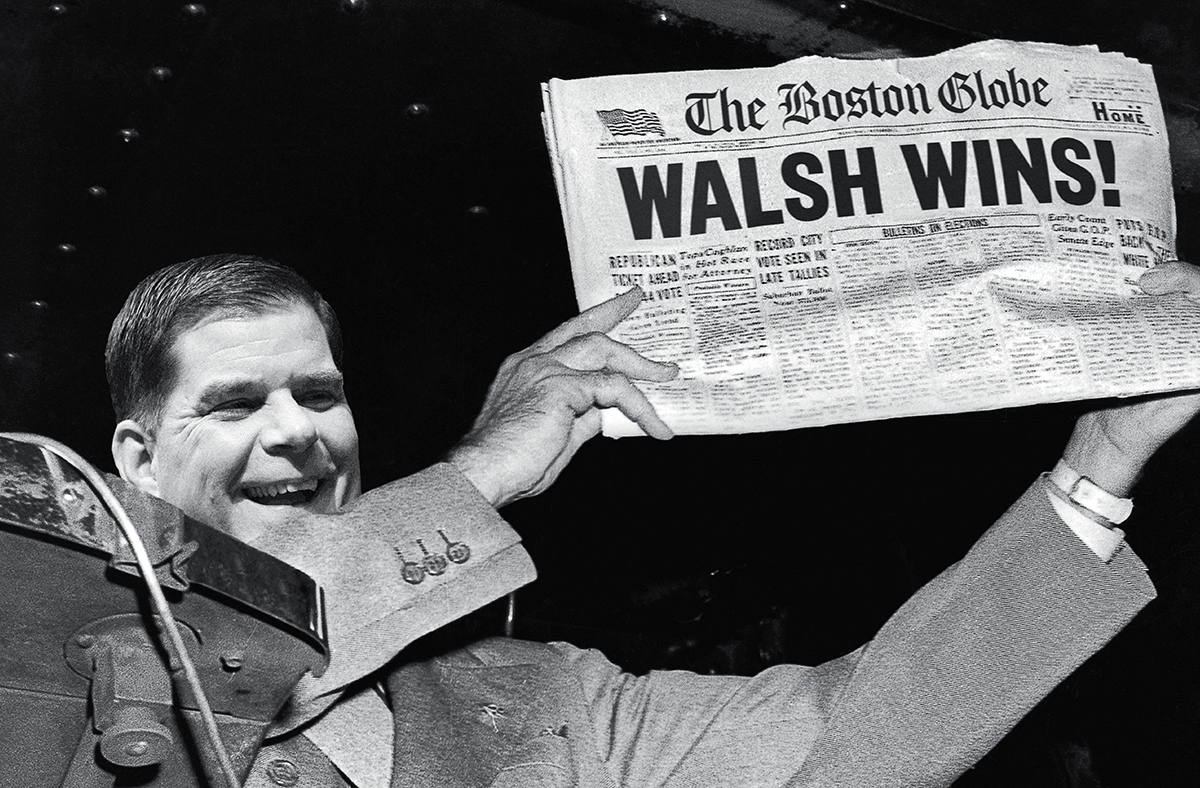

Walsh Wins!

Forget the election, Marty, we’re calling it for ya. From cops to schools to who to fire, here’s your blueprint for the next four years. (You can thank us later.)

Edited by David Bernstein

Illustrations by Trey Ingram

Source portrait by Paul Marotta/Getty Images

Congratulations, Marty Walsh! You’ve won a second term as mayor of Boston. Sure, we have to go through the motions of casting and counting ballots, but let’s not pretend: Incumbent mayors don’t lose here, and you’re in no danger of being the exception. Come November, you’ll be heading into a second four-year term—with a surging cache of political capital. The big question is: What will you do with it?

Your predecessor, Tom Menino, deftly built his influence, but he was always worried about the next election—meaning he seldom took risks that might have cost him allies or lowered his approval rating. In your first term, and especially over the past year, it looks like you’ve followed his lead.

We get it, though—big decisions weigh heavy, and it can be lonely at the top. So, in the spirit of civic duty, we decided to lend a hand, asking experts and politicos all over the city how you could really make your mark. Here, courtesy of your dear friends at Boston magazine, is a blueprint for what you should try to get done in the next four years. Some goals are big, some small. Some are easier and some tougher. Some would require political courage—and cost political capital. But all would make the city better, and in the long run we think that will mean more to you than a few points in future polls.

Now get to work.

1. Connect downtown to Dorchester (and beyond).

While construction cranes soar high above the skylines of downtown, South Boston, the Fenway, Chinatown, and the South End, people in those neighborhoods enjoy a newly rejuvenated city life. To the south of all that, though, a good share of Boston looks and feels the same as it has for decades. From Dorchester, Mattapan, and Hyde Park, downtown increasingly looks like Disney World as viewed from suburban Orlando.

While construction cranes soar high above the skylines of downtown, South Boston, the Fenway, Chinatown, and the South End, people in those neighborhoods enjoy a newly rejuvenated city life. To the south of all that, though, a good share of Boston looks and feels the same as it has for decades. From Dorchester, Mattapan, and Hyde Park, downtown increasingly looks like Disney World as viewed from suburban Orlando.

That’s no secret to the Walsh administration. The Imagine Boston 2030 blueprint, finalized in July, devotes a full section to developing the “Fairmount Corridor”—which runs from Hyde Park through Mattapan and Dorchester up to Newmarket—by promoting the recently improved Fairmount commuter-rail line and the proposed Indigo Line, which will eventually connect neighborhoods in the residential south to growing job markets in Newmarket, Widett Circle, and Dudley Square. There’s also a way to fix the transportation woes without endless infrastructure projects, says Marc Draisen, executive director of the Metropolitan Area Planning Council: more bus lines, with more-frequent routes and the flexibility to alter those routes as neighborhoods change. “It’s the bus lines that move most low- and moderate-income people around the city,” Draisen says. The catch? Infrastructure plans need buy-in from Governor Charlie Baker.

What Walsh can, and should, do on his own is carefully guide the ongoing development of Newmarket, between the South End and Uphams Corner, which was rezoned by the city three years ago. The Imagine Boston 2030 report correctly laments that the area and Widett Circle currently “separate some of the communities with the most persistent disparities from the growing economic engines of the city’s fastest-growing job centers.” Put another way, it’s a void between the Expressway and “Methadone Mile,” essentially an open-air drug market near Boston Medical Center. Done right, Newmarket could bridge the divide with a combination of commercial businesses, transit-oriented development, and pedestrian-friendly retail in all directions.

2. Close schools.

When it comes to improving Boston schools, the obstacles can seem insurmountable. Shrinking budgets are just the tip of the iceberg. Still, it might be possible to chip away at some of the more intractable problems by attacking those that are firmly rooted in the ground. In other words, it’s time to take a hard look at the brick-and-mortar schools themselves.

When it comes to improving Boston schools, the obstacles can seem insurmountable. Shrinking budgets are just the tip of the iceberg. Still, it might be possible to chip away at some of the more intractable problems by attacking those that are firmly rooted in the ground. In other words, it’s time to take a hard look at the brick-and-mortar schools themselves.

Across the city, school buildings are underused and out of date; nearly two-thirds of them were built before World War II. In addition, the number of students has declined by more than 1,000 over the past 10 years—disproportionately in middle schools. That translates into wasted dollars going toward teachers, janitors, maintenance, and other costs. “We’re spreading school dollars thinly, because we’ve got excess capacity in the system,” says Sam Tyler, president of the Boston Municipal Research Bureau, which analyzes the city’s finances and services. The city is staring at inevitable renovations and major efforts to redesign classrooms for 21st-century learning.

To improve the system, Walsh needs to do something that a lot of people are going to hate: close and consolidate some schools, starting right now. This will lead to fewer employed teachers and support staff, which of course will piss off the Boston Teachers Union. Even now, parents have begun organizing against closures, and many more will join the cause when a plan comes out showing their kid’s school is on the list. But everybody will win in the end. The resulting savings could fund teacher training and support, classroom resources, and new programming. “There’s no opportunity for reinvestment,” says one longtime Boston education activist who asked not to be named criticizing the mayor’s foot-dragging, “until somebody puts on their big-boy pants and gets it done.”

3. Put fresh eyes on the BPD.

For a very long time, the Boston Police Department has relied on friendly mayors and a generally low city crime rate to brush off calls for change. As the city grows, however, the problems festering under the BPD just won’t fly. A 2015 audit, which barely skimmed the surface, flagged a host of big-ticket issues: Fitness standards for veteran officers are lacking; supervision rules differ from district to district; policies on everything from pursuit driving to the use of deadly force are woefully out of date; and overtime accounting is, to be blunt, kind of a hot mess.

For a very long time, the Boston Police Department has relied on friendly mayors and a generally low city crime rate to brush off calls for change. As the city grows, however, the problems festering under the BPD just won’t fly. A 2015 audit, which barely skimmed the surface, flagged a host of big-ticket issues: Fitness standards for veteran officers are lacking; supervision rules differ from district to district; policies on everything from pursuit driving to the use of deadly force are woefully out of date; and overtime accounting is, to be blunt, kind of a hot mess.

What the force needs is an independent, top-to-bottom review for efficiency, organization, and adherence to best practices—with a commitment to fully cooperate with the review, publicly release the findings, and follow through. “It would come up with recommendations that might be controversial, but necessary,” says Tyler, of the Boston Municipal Research Bureau. No mayor wants to go to war with his city’s cops, but these changes are overdue. Consider the Community Ombudsman Oversight Panel, finally implemented 11 years ago in bare-bones fashion by Tom Menino after years of public outcry. Walsh asked the members of that civilian review group for recommendations to make it an effective body. So far he’s made small tweaks, but he should go further.

So what can Marty do to make BPD oversight work? He and Police Commissioner William Evans need to understand that their own good intentions and legitimate progress are not enough to ensure either best practices or the trust of residents. They should view independent analysis as a benefit, not a threat.

4. Clean up the Boston political machine.

Walsh comes from the old world of Massachusetts machine politics—a dated system that produced the Sal DiMasi scandal, after which the House speaker went to prison for corruption and fraud; and the Probation Department patronage scandal, which exposed a rigged hiring system. Not to mention an endless parade of backroom, back-scratching deals. Walsh shouldn’t be painted with the same brush, but he has publicly criticized the Probation Department convictions in a way that, as the Boston Globe rightly put it, seemed to suggest a certain comfort with putting patronage over merit-based hiring. The result is an undefined status quo in which nobody agrees on what is right or wrong, and everybody is afraid to discuss it.

Walsh comes from the old world of Massachusetts machine politics—a dated system that produced the Sal DiMasi scandal, after which the House speaker went to prison for corruption and fraud; and the Probation Department patronage scandal, which exposed a rigged hiring system. Not to mention an endless parade of backroom, back-scratching deals. Walsh shouldn’t be painted with the same brush, but he has publicly criticized the Probation Department convictions in a way that, as the Boston Globe rightly put it, seemed to suggest a certain comfort with putting patronage over merit-based hiring. The result is an undefined status quo in which nobody agrees on what is right or wrong, and everybody is afraid to discuss it.

Walsh, uniquely, can do something about it. Once the criminal cases against aides Kenneth Brissette and Timothy Sullivan, both charged with extortion, are adjudicated, the mayor should launch a high-profile effort to promulgate a set of ethical standards to guide City Hall, with the presumption that they should apply to the State House as well. It’s impossible to foresee all situations or to erase all gray areas, but there are plenty of circumstances in which City Hall could use some lines to draw inside of. When, for instance, is it appropriate to help somebody get a job or suggest using union labor? When is it right for the administration to assist one development and hinder another? The answers will sometimes be legal in nature, but more often will be matters of ethics or propriety. For without a big public show that the old political machine’s days are numbered, there is no reason for Bostonians to assume the dirty practices of patronage politics are behind us.

5. Celebrate Boston’s arts and culture.

From the Puritans’ ban on musical instruments in church to the endless series of failed attempts to bring ambitious events to Boston, influential city leaders and cranky residents have been more interested in stymieing new culture than celebrating it. “We own the brand on history,” says John Tobin, vice president of city and community affairs at Northeastern University. “We don’t own the brand on contemporary as much as we should.” Despite the city’s stuffy reputation, though, thoroughly modern public art has reared its head in Dewey Square and on the Hancock building; Boston Calling ranks among the country’s best music festivals; and the restaurant scene is near, if not on, the cutting edge. There’s a well of creativity bubbling just under the surface that could enhance Boston’s image among smart young professionals. It just needs to be tapped.

From the Puritans’ ban on musical instruments in church to the endless series of failed attempts to bring ambitious events to Boston, influential city leaders and cranky residents have been more interested in stymieing new culture than celebrating it. “We own the brand on history,” says John Tobin, vice president of city and community affairs at Northeastern University. “We don’t own the brand on contemporary as much as we should.” Despite the city’s stuffy reputation, though, thoroughly modern public art has reared its head in Dewey Square and on the Hancock building; Boston Calling ranks among the country’s best music festivals; and the restaurant scene is near, if not on, the cutting edge. There’s a well of creativity bubbling just under the surface that could enhance Boston’s image among smart young professionals. It just needs to be tapped.

Armed with a skilled arts and culture chief, Julie Burros, and a decent (if vague) blueprint in the new Boston Creates cultural plan, Walsh should continue to make more room for the arts. According to a recent report from the Boston Planning & Development Agency, there’s a large, unmet demand for affordable rehearsal and performance spaces, while many of the more expensive rooms are underused. In other words, all that’s needed are some smart approaches to spur an explosion of the performing arts.

There are other, ah, cultural challenges that City Hall might address, too. Despite not-guilty verdicts last month, the allegations of Teamster threats against Top Chef host Padma Lakshmi, and reports of ham-handed union pressures on Boston Calling, have been reminders of why the city has a reputation of being difficult to deal with. Early shutdowns of public transportation and alcohol sales also don’t help. If Boston wants a cosmopolitan reputation, it needs to shed some of its close-minded ways.

6. Spread diversity and opportunity.

Two years ago, Colette Phillips asked Walsh how he was going to push the city’s business community to be more inclusive. The owner of Colette Phillips Communications and a longtime advocate for race and gender equality in the city, Phillips remembers him telling her, “‘I have to get my own house in order first, so when I talk to the business community about diversity and inclusion, I come from a place of credibility.’” The mayor’s efforts to make his own staff reflect the city’s mélange, while not perfect, have been serious. Now it’s time to push Boston’s employers—from trade unions to corporations and nonprofits—to provide equal opportunity for all. And Phillips, along with many others, wants to see Walsh use carrots rather than sticks to do it.

Two years ago, Colette Phillips asked Walsh how he was going to push the city’s business community to be more inclusive. The owner of Colette Phillips Communications and a longtime advocate for race and gender equality in the city, Phillips remembers him telling her, “‘I have to get my own house in order first, so when I talk to the business community about diversity and inclusion, I come from a place of credibility.’” The mayor’s efforts to make his own staff reflect the city’s mélange, while not perfect, have been serious. Now it’s time to push Boston’s employers—from trade unions to corporations and nonprofits—to provide equal opportunity for all. And Phillips, along with many others, wants to see Walsh use carrots rather than sticks to do it.

That could be trickier than it sounds. There will always be resistance from companies that don’t want to be told what to do—and really don’t want to think they’re losing city contracts when they feel they’ve done nothing wrong. That’s a big reason the city has been timid in using its procurement process to address inequalities in companies that receive city contracts. To avoid playing the heavy, Walsh should work with the business community—the Greater Boston Chamber of Commerce, for instance—to define a set of standards for ensuring equal opportunity and pay, internally and in their procurement processes. Organizations that adopt those standards could earn some sort of good-corporate-citizen stamp of approval as an incentive. “We can become a best-practices city on issues of diversity and inclusion,” Phillips says. “That would be the best legacy for an Irish-American mayor of Boston.”

7. House the millennials.

Everybody knows Boston needs more affordable housing. And, by the usual definition, Walsh has done an impressive job of getting that ball rolling: expanding the low-income housing stock, improving the requirements that developers build affordable units along with high-end ones, and creating a pool of funds that can be used for future affordable housing projects. On the other hand, it’s hard to miss the rapid expansion of luxury housing. What’s lacking is the chance for Boston’s crucial workforce—bright, educated, middle-class young adults—to live in the city.

Everybody knows Boston needs more affordable housing. And, by the usual definition, Walsh has done an impressive job of getting that ball rolling: expanding the low-income housing stock, improving the requirements that developers build affordable units along with high-end ones, and creating a pool of funds that can be used for future affordable housing projects. On the other hand, it’s hard to miss the rapid expansion of luxury housing. What’s lacking is the chance for Boston’s crucial workforce—bright, educated, middle-class young adults—to live in the city.

To afford the average rent of a new downtown apartment, a couple needs to earn as much as $130,000. If you’re looking for a place where you can have a kid, a two-bedroom in Southie or Charlestown will likely set you back some $4,000 a month, according to RentCafe. Going farther out doesn’t help much, until you reach Roslindale and Allston-Brighton, where the morning commute becomes more difficult. There are, however, potential solutions that make creative use of subsidies and incentives that the city could orchestrate on its own. One example is the 14-floor Beverly building being developed near North Station, which will include a mix of units for both low-income households and those with incomes up to $198,000—a sweet spot for the kinds of younger professionals that the city’s growth demands. We need more of that, and fewer shiny skyscrapers in the Seaport.

8. Improve not-quite-universal Pre-K.

Sometimes, you make a big promise you can’t deliver on. For Walsh, that’s universal pre-kindergarten. He campaigned on it in 2013, suggesting Boston sell City Hall to pay for it, and touted it in his first State of the City address. His latest plan is to pay for it using a portion of the state’s Convention Center Fund, roughly $16.5 million a year, but that gambit needs to be approved by Governor Baker and state representatives, who are unlikely to use state money to fund universal pre-K in Boston while rejecting plans to fund it elsewhere in the state. In short, it’s not going to happen anytime soon. Walsh likely won’t admit defeat before the election, but it’s time for him to pivot to improving the pre-K that exists now.

Sometimes, you make a big promise you can’t deliver on. For Walsh, that’s universal pre-kindergarten. He campaigned on it in 2013, suggesting Boston sell City Hall to pay for it, and touted it in his first State of the City address. His latest plan is to pay for it using a portion of the state’s Convention Center Fund, roughly $16.5 million a year, but that gambit needs to be approved by Governor Baker and state representatives, who are unlikely to use state money to fund universal pre-K in Boston while rejecting plans to fund it elsewhere in the state. In short, it’s not going to happen anytime soon. Walsh likely won’t admit defeat before the election, but it’s time for him to pivot to improving the pre-K that exists now.

The vast majority of Boston parents manage to find pre-K for their kids. The problem, though, is that the quality varies, and access to good programs can depend on income, location, or even luck. Menino made strides by expanding and improving BPS’s offerings, which now serve more than 40 percent of the city’s 6,000 four-year-olds. The rest rely on a mishmash of Head Start, community-based centers, parochial schools, private or charter schools, and family-based daycare providers. Many are good; some aren’t. And the disparate models and scattered oversight bodies force parents to chase down a seat for their child through a maze of sources.

The Walsh administration should create a single portal for those parents—perhaps stealing some ideas from the Affordable Care Act’s healthcare-insurance exchanges. That won’t eliminate disparities, especially without the funding to subsidize more of the costs for more families. But it could give the neediest children a better shot at quality pre-K, while offering a clear path for providers and philanthropies to identify and fill in gaps.

9. Follow through on Olympic promises.

The Boston 2024 Olympic bid is dead, and Walsh’s reelection puts the whole embarrassment to rest. Still, while the idea to host the games was largely rejected, there were several worthwhile ventures attached. Namely, the promise to spruce up the city, with expenses picked up by the prefect trifecta of private, state, and federal funders. Ultimately, we won’t get our hands on all of that free money, but it shouldn’t mean the projects vanish. Instead, Walsh should pluck the best improvements from the old Boston 2024 plans and push hard to ram them through.

The Boston 2024 Olympic bid is dead, and Walsh’s reelection puts the whole embarrassment to rest. Still, while the idea to host the games was largely rejected, there were several worthwhile ventures attached. Namely, the promise to spruce up the city, with expenses picked up by the prefect trifecta of private, state, and federal funders. Ultimately, we won’t get our hands on all of that free money, but it shouldn’t mean the projects vanish. Instead, Walsh should pluck the best improvements from the old Boston 2024 plans and push hard to ram them through.

Franklin Park: Walsh is making good on $5 million worth of badly needed improvements to the pathways and entrances, but the proposed renovation to White Stadium, and new public transportation to get you there, have faded into memory. Both would have a positive impact on Dorchester and Mattapan—Franklin Park could become the sports-centered family gathering place that the parkway fields are in West Roxbury and Roslindale. And might we even dream of the once-proposed swimming pool?

Kosciuszko Circle: Harder to navigate than to spell, the rotary where Columbia Road meets Morrissey Boulevard near the UMass Boston campus is a daily disaster. Boston 2024 intended to fix it as part of its plan for an Olympic Village on the peninsula. Later, the city wanted Robert Kraft to fix it as part of plans for a soccer stadium. Today, all that’s being done is a $700,000 state study.

Harambee Park: An underappreciated gem that straddles Dorchester and Mattapan, the Boston 2024 tennis venue would have gotten a new 2,500-seat stadium and an upgrade to the existing outdoor courts. The improvements—and the attention of the Olympic competition—would have turned the site into a destination for athletes from all over the area. That’s worth finding a way to do despite the loss of the games.

10. Lead the Trump resistance.

One of the great moments in Walsh’s first term arrived quietly in June, when the city launched its new climate website, climatechange data.boston.gov. A thumb in the eye of Donald Trump’s administration, the site posts reports that have recently been removed from the president’s newly climate-hostile Environmental Protection Agency. Sure, Walsh’s step wasn’t necessary—the information remained available elsewhere—but that was the beauty of the idea. Posting the material served as a perfect, and perfectly Boston, jab at Trump.

One of the great moments in Walsh’s first term arrived quietly in June, when the city launched its new climate website, climatechange data.boston.gov. A thumb in the eye of Donald Trump’s administration, the site posts reports that have recently been removed from the president’s newly climate-hostile Environmental Protection Agency. Sure, Walsh’s step wasn’t necessary—the information remained available elsewhere—but that was the beauty of the idea. Posting the material served as a perfect, and perfectly Boston, jab at Trump.

As such, it is incumbent upon Walsh to step up as a regional, if not national, leader of the anti-Trump resistance, particularly on issues important to cities. His instincts for needling Trump are pitch-perfect—Walsh, after all, appeals to many of the same voters that Trump does. In fact, given the number of white working-class and union-household Walsh voters who supported Trump, it’s surprising the mayor has been so willing to attack our commander in chief. Still, because he comes across as an authentic populist compared with Trump’s Richie Rich act, voters might listen a bit more when he speaks out against the Muslim ban, barring transgender individuals from serving in the military, or withdrawing from the Paris climate accord. Despite being a die-hard Democrat, Walsh doesn’t seem as party-driven as other prominent Trump bashers, including Senator Elizabeth Warren.

It’s fun to watch Walsh respond to each new Trump outrage, but to emerge as a national leader of the resistance, he and his administration need to become more proactive, with sustained, planned campaigns within Boston and beyond. Trump has yet to enact policies on some of Walsh’s most cherished issues, such as labor unions and gun control, but at this rate it won’t be long—so there’s still plenty of fighting to be done.

Franklin-Hodge is doing heroic work updating the city’s horrifically outdated systems. To keep him from going back to the private sector, give him more authority.

Franklin-Hodge is doing heroic work updating the city’s horrifically outdated systems. To keep him from going back to the private sector, give him more authority. Part of economic development chief John Barros’s ace team, Jones has worked on youth summer jobs and courting GE. What else can she do?

Part of economic development chief John Barros’s ace team, Jones has worked on youth summer jobs and courting GE. What else can she do? One of the few remaining Menino holdovers, Dillon has shown that there’s nobody better to oversee Boston’s difficult growth phase. Never let her go.

One of the few remaining Menino holdovers, Dillon has shown that there’s nobody better to oversee Boston’s difficult growth phase. Never let her go. Managing the Boston Fire Department is a notoriously tough and thankless job. You don’t hear much about Finn because he’s quietly effective.

Managing the Boston Fire Department is a notoriously tough and thankless job. You don’t hear much about Finn because he’s quietly effective. The problems have not all been his fault, but he’s losing the faith of the people he needs on his side to make progress. Cut him loose.

The problems have not all been his fault, but he’s losing the faith of the people he needs on his side to make progress. Cut him loose. Golden rebranded the city’s much-maligned planning agency, but now it’s time for a fresh face to lead it into the future.

Golden rebranded the city’s much-maligned planning agency, but now it’s time for a fresh face to lead it into the future.