Massachusetts Is Finally Removing Its Confederate Monument

MEMORIAL PHOTO VIA RON COGSWELL ON FLICKR/CREATIVE COMMONS

Massachusetts will finally be removing its one and only Confederate monument this weekend, state officials say.

The memorial, which is dedicated to the memory of imprisoned Confederate soldiers and is located outside Fort Warren on Georges Island in Boston Harbor, has been boarded up since June. Officials had been mulling exactly what to do with it since then. Now, it seems, they have a plan. Over Columbus Day weekend, state workers will be taking it to the state archives at the UMass Boston campus for safekeeping out of the public eye, the state secretary’s office tells the Boston Globe. It will be kept there until it can be returned to the United Daughters of the Confederacy, which put it there.

Gov. Charlie Baker had signaled his support for removing the monument. His spokeswoman Lizzy Guyton said in June he believed it was time to “explore relocation options.” That came amid a national debate about what to do with the symbols idolizing or commemorating the secessionist soldiers of the Civil War—many of which sprung up in American cities during Jim Crow and the Civil Rights Movement, and which opponents say are inappropriate odes to militants who sought to defend the institution of slavery and to secede from the Union.

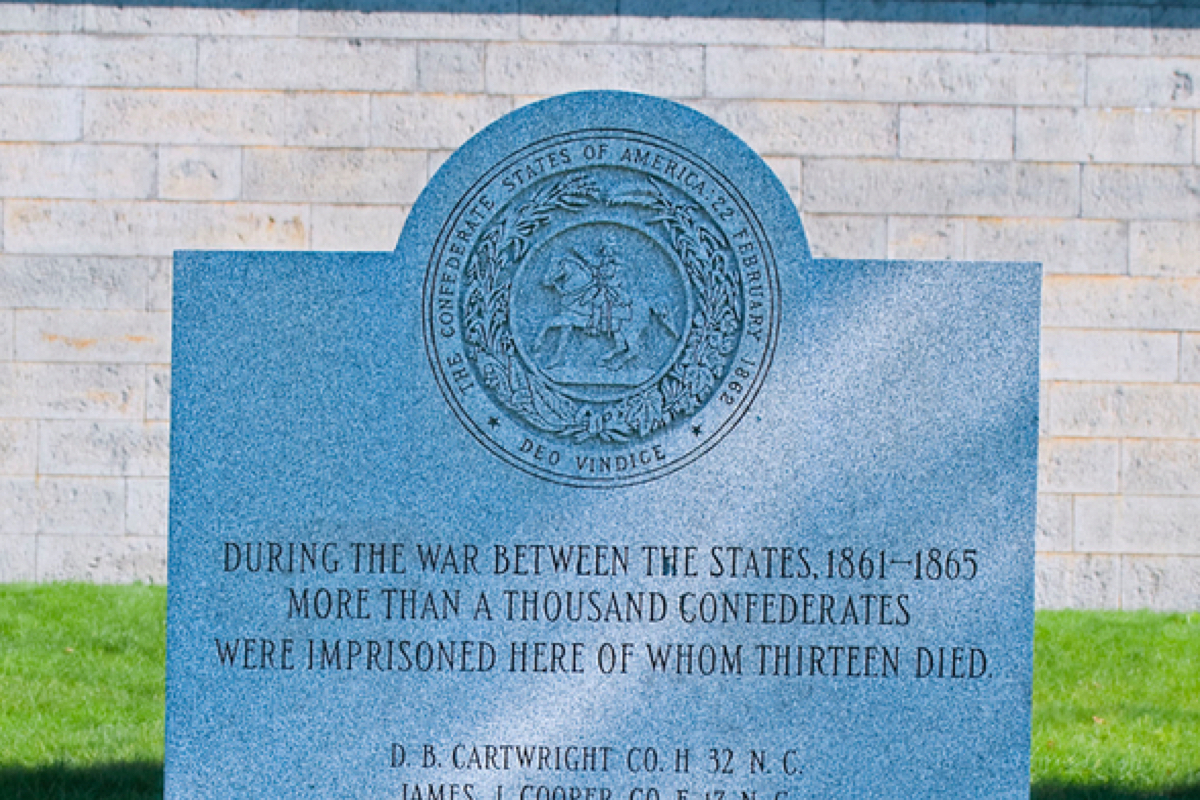

Massachusetts’ monument was erected in 1963, when the centennial of the war coincided with national upheaval over racial inequality. It was sponsored by the United Daughters of the Confederacy, a group that promotes the mythology of the “Lost Cause,” portraying the Civil War (which it calls the “War Between the States”) as being about states’ rights and Confederate culture, not a showdown over the right to own enslaved Africans. In this case, the memorial is to Confederate soldiers who were held prisoner by Union troops.

“During the War Between the States, 1861-1865,” the monument’s inscription reads, “more than a thousand Confederates were imprisoned here of whom thirteen died.”

The group, which has seen its monuments uprooted around the country this year, has defended them from critics, denounced “any individual or group that promotes racial divisiveness or white supremacy,” and called for them to remain where they are.

“We are saddened that some people find anything connected with the Confederacy to be offensive,” its president Patricia M. Bryson wrote in a statement in August, which did not mention Boston’s in particular. “Our Confederate ancestors were and are Americans. We as an Organization do not sit in judgment of them nor do we impose the standards of the 21st century on these Americans of the 19th century.

“It is our sincere wish that our great nation and its citizens will continue to let its fellow Americans, the descendants of Confederate soldiers, honor the memory of their ancestors. Indeed, we urge all Americans to honor their ancestors’ contributions to our country as well. This diversity is what makes our nation stronger.”