UMass Keeps Watch over Boston Harbor with Robots and Drones

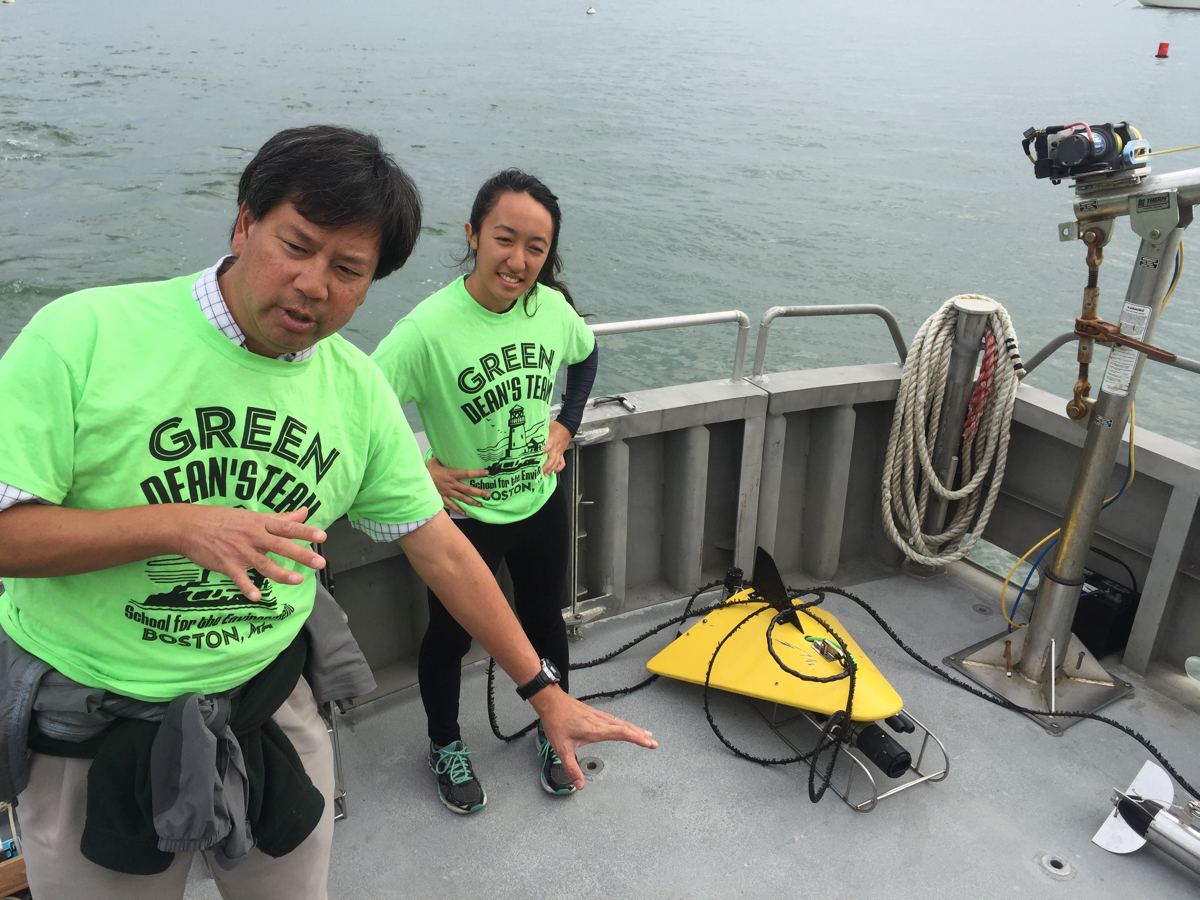

Bob Chen, scientist and UMass professor, and Kelly Luis, phd student, show off the MiniShutle robot aboard a research vessel called the Columbia Point. Photo by Spencer Buell

It really wasn’t all that long ago that the Harbor was an infamously gross mess. Years of neglect had turned it into the “dirtiest harbor in America,” and it was only because Boston made cleaning it up a priority and spent billions doing so that it’s the relatively clean, vibrant ecosystem it is today. Making sure it stays that way is a full-time job, and increasingly, as the technology has gotten cheaper and more accessible, it involves robots and drones.

“The cool thing about oceanography as a field is that they’ve always had to invent new technologies because they always have new problems,” says Robyn Hannigan, founding dean of UMass Boston’s School for the Environment. “It started with the clean-up of the Harbor 30 years ago and it’s just progressed from there.”

Robotics and drone technology has totally changed the way scientists oversee the precious resource hugging Boston’s coast, Hannigan says, and it’s broadened the scope of what we know about it. A sampling of those new tools was on display Wednesday afternoon on a HUBweek-sponsored boat tour aboard the Columbia Point, the hulking research and tourism vessel that regularly trawls the Harbor for data. Attendees of the weeklong art and technology festival were invited to climb onto the boat to see the cutting-edge doodads hurled overboard and put to use.

Among the fancy new stuff used on the boat was something called an Imaging Flow CytoBot, which sucks in water, runs it through a tube, and rapidly takes photos of every tiny creature that passes in front of its powerful camera. You can watch from a computer in real time as the oddly shaped little microorganisms pass through it and are recorded into a database, which can be examined for signs that water quality is impacting microbes. The device is one of only 15 in the world.

Then there’s the Floating Radiometer, a buoyant disk with a long tube attached to it, which points down, and two columns sticking out on either side, which point up. It uses sensors to capture the color of the water below it (color is critical in understanding water quality), then relay data to satellites, which snap pictures of the Harbor from above. UMass researchers invented the Floating Radiometer, and right now it’s the only one in the world.

This lil guy helps satellites study water quality by monitoring underwater light. pic.twitter.com/6ReUxT9o3P

— Spencer Buell (@SpencerBuell) October 11, 2017

On top of that, literally, scientists are now using research drones, which can take photos of the water’s changing colors from above, or even hover inches above the robots floating in the water, to help scientists learn about how chemicals are transferred between the water and air.

Another marvel aboard the Columbia Point is its MiniShuttle, a kite-shaped robot equipped with sensors that gets thrown into the water attached to a rope. As it weaves up and down behind the boat, it analyzes temperature, organic particles, dissolved oxygen, and other substances of interest. It “sees chemicals,” says Bob Chen, a UMass professor and chemical oceanographer, and is an efficient way to gather helpful data on how the Harbor is changing, and how quickly.

Here’s the MiniShuttle, which gets dragged behind the boat and looks for changes in water chemistry. pic.twitter.com/1PGPTR14Wy

— Spencer Buell (@SpencerBuell) October 11, 2017

There are always new threats, be it from climate change or other man-made contributions to the ocean’s makeup. A relatively new focus has been on the presence of pharmaceutical drugs, which spread from sewage into the ocean water. As the drugs’ impact on marine life is not yet fully understood, researchers help the Massachusetts Water Resources Authority keep an eye on how they are interacting with the ecosystem.

Chen says that at the heart of the researchers’ work—the investment, the inventions—is a shift in how this generation of Bostonians thinks about our Harbor. “The remarkable thing about the Boston Harbor cleanup was that we used to have our backs turned to this environmental resource,” he says in a speech to a crowd of a few dozen people on the boat’s upper deck. “It was dirty and it smelled bad and we didn’t like it and didn’t want to be anywhere near it.”

Now, property values are soaring near the coast, and concerns have mounted over how sea-level rise will accelerate erosion and threaten the Harbor Islands and low-lying parts of the city. “The change in the relationship with the environment has been dramatic,” he says.

Still, says Hannigan, the UMass dean, the ocean is not yet getting the respect it deserves, and there are still too few people pursuing careers in the field. That might sound surprising—you’d assume people are clamoring for jobs using robots in the ocean—but she says it’s true. “We need more people going into marine technology,” Hannigan says. “We’re not training engineers to work in the ocean. The ocean is the thing that controls this planet, and yet we don’t have the best minds creating new technologies.”

That future may just have been on the boat on Wednesday. Alongside the curious adults aboard the Columbia Point were Carter and Zoe Dambreville, ages 9 and 11, of Lower Mills. Both say they are interested in science, and they watched in awe as various pieces of equipment were lowered into the water to survey the ocean floor and beam data into space. Zoe liked learning about how sonar, the ocean floor-mapping technology, works. On this boat, the process is aided by a missile-shaped device called an Edgetech 4125. “It was making sounds to take pictures,” she tells me. “It was pretty interesting.” Carter says his favorite part of the afternoon was when he was allowed to get an up-close look at the Floating Radiometer. “It was connecting to the satellite and to the ocean,” he says, adding, “Everything they’re doing is cool.”

Photo by Spencer Buell