The Subtle Art of Being Ernie Boch Jr.

On the verge of turning 60, the billionaire Trump supporter has jettisoned his car dealerships, is building a mausoleum in his backyard, and now wants to save the arts in Boston—he thinks.

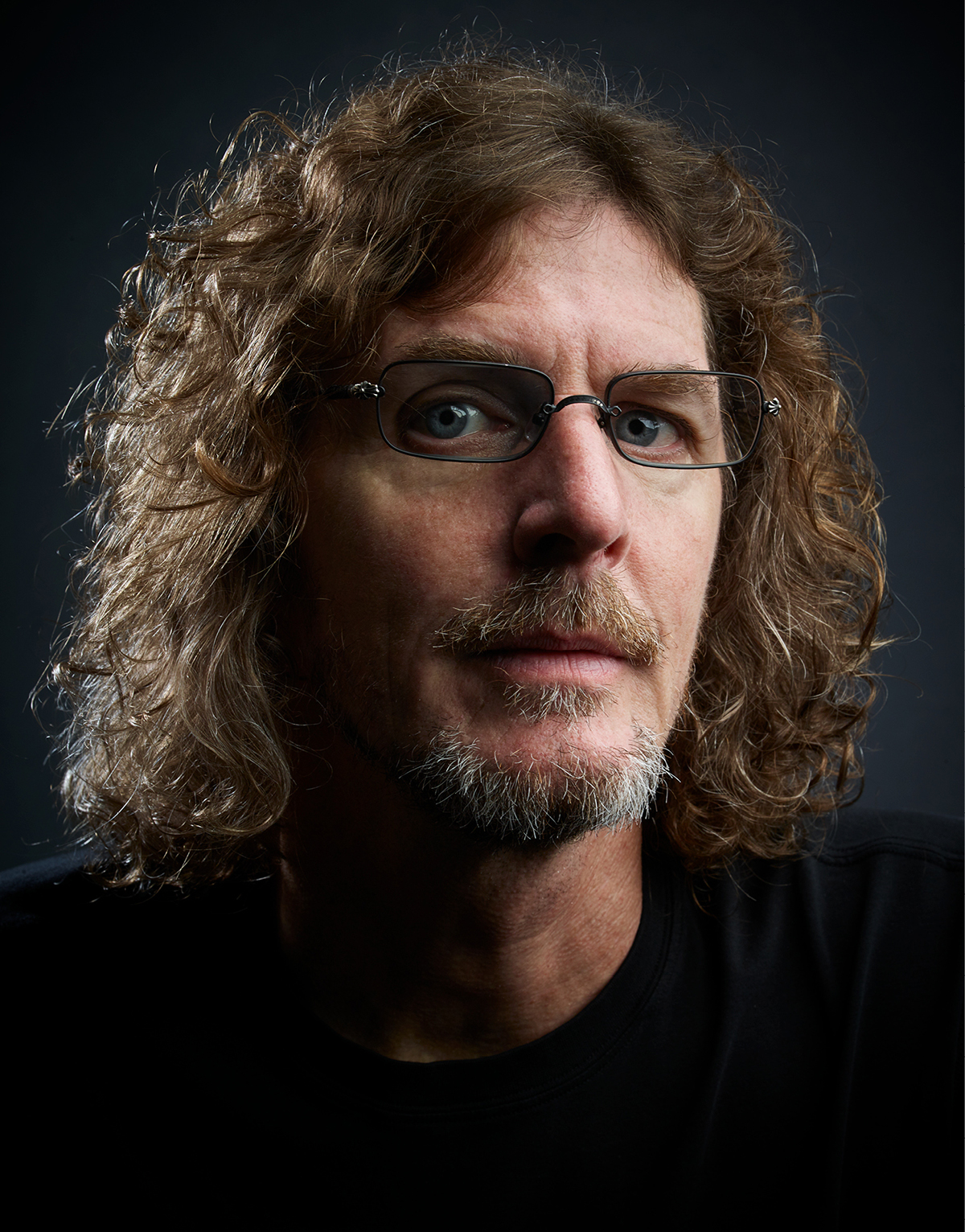

Photograph by David Yellen

Then there is the, uh, locker-room talk. One afternoon, Boch and I are slogging around Boston for a handful of Music Drives Us events with his in-house photographer, Rebecca, and the philanthropy’s fundraising director, Jackie. In between photo ops, he treats us to stories that are as objectionable as they are amusing. In one, a woman propositions him at a bar by claiming she’ll have sex with him if he dances with her; the nights ends in naked fisticuffs when her boyfriend discovers the two of them in her bedroom. At one point, half joking, I suggest to Jackie and Rebecca that they file an HR complaint. They laugh uncomfortably, but seem to tolerate their boss’s behavior with resignation. That’s Ernie being Ernie, their eye rolls say.

Still, I wasn’t entirely surprised when I learned of a 1992 lawsuit filed against Boch Oldsmobile. In that suit, a sales manager named Mary Burman alleged that Boch, also a manager at the dealership, referred to female customers as “bitch,” “pussy,” and other derogatory terms. After one dispute, Burman claimed, Boch yelled at her, “You fucking cunt. My name is on the building and I can do anything I want.”

In 1990, she submitted a complaint to the Massachusetts Commission Against Discrimination; a day later she was fired. Her ensuing unlawful termination suit lasted more than three years before it was ultimately dismissed. Boch denies Burman’s accusations, calling her “disgruntled.” My attempts to reach Burman were unsuccessful.

Still, those who’ve been on the receiving end of Boch’s generosity tend to give him the benefit of the doubt. “It’s hard to criticize his politics when he works so hard to make the world a better place,” says Shumlin, whom Boch helped by contributing to Hurricane Irene relief, a statewide college fund, and more.

Still, the Trumpian aspects of Boch’s persona are no doubt unsettling to the various stakeholders—in the Boston Public Schools, on the board of the Boch Center—invested in his patronage. “The one thing Ernie and I don’t agree on is politics, so we try not to talk about that,” says the Wang’s Joe Spaulding. “Every once in a while—it’s rare—someone tells me, ‘It’s terrible what you’ve done.’ I think they don’t know Ernie, and if they did know Ernie, and Ernie wasn’t put into the box that he is, people would realize he’s one of the most compassionate, amazing people I’ve met.” Perhaps, but if Boch finds himself in a box, it is one of his own making.

On the morning of my second day in Boch’s guesthouse, I rise late and amble over to the main property around 10:30 to locate breakfast. There I meet Debbie, Boch’s chef, housekeeper, and all-around den mother. “Ernie can dress himself,” she says, but besides that he is reliant upon her to keep his domestic life together. Every morning, she cooks him the same thing: a three-egg-white omelet with spinach and pulled chicken, alongside a frothy, almond-milk cappuccino beverage. She seems disappointed when I opt for an English muffin.

When I finish eating, Boch is in the midst of the photo shoot for this article. The bulk of it takes place in a tricked-out guitar room above one of his garages, which is notable not only for the sheer volume of rare axes, but also for the hideous and/or discontinued models Boch seems to relish. One of them is a disorienting upside-down flying-V Gibson that makes your eyeballs hurt; another, a gnarled brown atrocity, reminds me of the Necronomicon from Army of Darkness.

The photographer, David Yellen, repeatedly commands Boch to lick his guitar. Boch repeatedly complies. Perhaps unaccustomed to the flipped power dynamic, Boch seems particularly receptive to being bossed around. In general, this bout of command-and-control is rare, though. After Yellen is finished, Boch’s rambling schedule picks up where it left off.

The day is consumed with Music Drives Us business, punctuated by an odd series of juxtapositions. First, we drive to Malden to check in on a public school Boch supplied with new instruments. Showing up in a stretch limousine to a school in which 53 percent of students are “economically disadvantaged” would have been icky enough, even if we hadn’t then washed it down with a lunch of oysters and filet mignon at the Capital Grille.

Later in the day, we travel to Fenway Park to film a promotional spot on NESN. Boch spends his time earnestly plugging the virtues of music education for the underserved; he spends the ride back to Norwood recounting the time he got temporarily blacklisted from NESN for telling Heidi Watney she “looked hot” on the air.

By the time we get back to the compound in the late afternoon, I’m spent, and that’s before Boch takes me on a comprehensive tour of his estate that includes everything from his home-security system to an outdoor amphitheater. A bit put off by the conspicuous consumption, I’m readying to ask some pointed question about wealth disparity when he points to a closet in his basement.

“Have you ever seen people on the side of the street holding up signs?” he asks. “You know, ‘Please help me,’ or whatever. Do you ever read those signs? Like really read them?” Maybe? “Pay attention to them! They are amazing, they are heartbreaking, and they are funny. So every time I see a sign, I buy it. I’ve paid anywhere from $10 to $200 for a sign.” Long story short: “I’m going to get some art gallery on Newbury Street, I’m going to frame them up and write all the muckety-mucks around town and sell them, and give the money to the shelters.”

Somehow, I’ve got a feeling that fetishizing literal cries for help as objets d’art won’t go over well. And yet, it’s clear that Boch is trying to help. “With Ernie, there aren’t all kinds of lawyers, return on investment, that kind of thing,” says WBCN veteran and unofficial Boston countercultural historian David Bieber, who has collaborated with Boch on a number of archival rock music projects. “He will respond immediately and worry about the details in the aftermath. He has an altruistic streak that says, ‘I can remedy this.’”

The same instinct that motivates Boch to buy a DeLorean also motivates him to risk his reputation by befriending Trump. Life is short and it makes him happy. In other words: Fuck it. And that enthusiasm can be infectious. His habit of listening only to Beatles satellite radio set me on a Fab Four kick I couldn’t shake for weeks. Ask him to drill a little deeper into his various compulsions, though, and you may be disappointed. When the tour mercifully ends, I fix myself a martini and sit down at the kitchen counter with Peggy and Ernie, who produces two Debbie-made plates of steak salad out of the fridge. Soon, he’ll pack his bags for a business trip to Italy with Lord’s & Lady’s hair magnate Mike Barsamian, who is for some reason joining him. Time is short, so I try to inject some gravitas into the proceedings. Transcript is as follows:

Ernie, do you think about your legacy?

“My legacy? Yeah! Doesn’t everybody? I mean, the best definition of what is the meaning of life is, ‘The meaning of life is to give life meaning.’ And I believe that.”

Okay.

“So I think a legacy is important.”

What is yours going to be?

“I think a legacy should be something that’s good. Like, Charles Manson will have a legacy. That’s not a good legacy.”

Very true, but not quite what I’m looking for. Peggy Rose helps him out a bit. “I think your legacy, being your publicist, is being a good father to your children, but also, you improve the lives of the people who work for you. You’re very generous.” Boch concurs that he’s “not a taker.” Peggy continues: “You feel music is part of who you are and you try to share it with other people. Mainly children in classrooms in schools, because that’s where the need is.”

Boch nods thoughtfully and doesn’t say anything for a moment. Then he holds up a half a lemon. “I learned this from Martha Stewart. It cleans the disposal.” And he sticks his hand down the sink.