TBT: Telling the Story of the Boston Tea Party through Artifacts

The Boston Tea Party wasn't a night of rage-fueled treason—it was part of a meticulously orchestrated protest.

Photo via Wikimedia Commons

“A NOBLE SIGHT—to see th’ accursed TEA

Mingled with MUD—and ever for to be;

For KING and PRINCE shall know that we are FREE.”

The unidentified author of this historic verse accounts the stealthy political act of December 16, 1773, one of the most well-known events that incited the Revolutionary War: the Boston Tea Party.

While every good American knows the basics of that night—a group of Patriots dressed as Native Americans dumped more than 300 chests of tea into the Boston harbor, protesting the British king’s latest taxation—very few know the specifics of what happened before or after. The event wasn’t even labeled as the Boston Tea Party until 1826, and at this time the term “party” was used to refer to the men involved, not the event itself (they were “of the Tea Party,” not “at the Tea Party”).

Protest of the Tea Act had actually begun over two weeks before, when the “Body of People” demanded the East India Company leave port and resign their consignees. The group of greater Boston citizens refused to let the tea be unloaded. It was common knowledge that the East India Company had ties with the royal government, and Americans felt the new tax favored consignees of this merchant, putting others’ businesses at risk.

After seventeen days of protest, the Patriots decided to take action. A group of men met at the home of Benjamin Edes, co-publisher of the radical newspaper Boston Gazette. The evening before the Boston Tea Party, they congregated to decide on a course of action. Although their deliberations were behind closed doors, Edes’s son, Peter, served the guests in an ornate punch bowl (now in the Massachusetts Historical Society’s collection of artifacts).

Edes family Tea Party punch bowl made by an unidentified maker in China, circa 1760-1773 / Photo courtesy of the Collection of the Massachusetts Historical Society

“I recollect perfectly well that in the afternoon preceding the evening of the destruction of the tea a number of gentlemen met in the parlor of my father’s house,” Peter would recall many years later, “how many I cannot say as… I was not admitted to their presence.”

The following evening, the men boarded the East India Company’s three ships, one simply asking the guarding official to look the other way. They were very careful to avoid any violence as they dumped the tea into the harbor—they wanted to be clear that their only target was the tea itself. So fastidious were the Patriots that when they had to break a lock to open a tea chest, they allegedly brought a new lock to one ship’s captain the next day.

This act was a political statement, not a robbery. In three hours, the men had dumped 42 chests containing over 92,000 pounds of tea. Only one man brought tea home with him that night, and it was by accident. The Bostonian Society has a small vial of tea leaves on display, which Thomas Melville was said to have shaken out of his boots and clothes after the dumping of the tea.

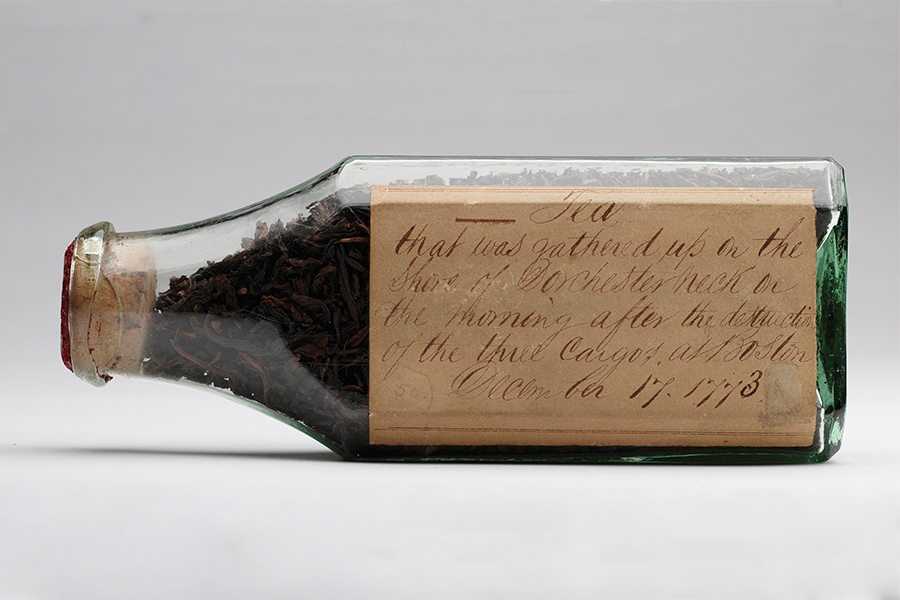

Tea leaves in glass bottle collected on the shore of Dorchester Neck the morning of 17 December 1773 / Photo courtesy of the Collection of the Massachusetts Historical Society

The next morning, Boston Harbor was filled with floating tea leaves. Kudos to the individual who bottled some soaked bits of tea found on the shore of Dorchester Neck—today it’s in the Massachusetts Historical Society’s collection of artifacts.

As time wore on, the revolution continued, but the Patriots of the Boston Tea Party didn’t gloat of their act. The first to confess their treasonous history were actually younger men who had moved outside of Boston in the early 1800s. There is minor speculation as to why silence was kept, only to be broken decades later (pride, reputation), but the truth persists that the first list of men involved in the Tea Party wasn’t published until 1835, and it was written anonymously.

Even now, nearly 200 years later, the exact identity and role of every man in the Boston Tea Party isn’t known. What we do know, however, is that this political act was an inciting incident to the Revolutionary War, and today, we can enjoy a cup of tea without paying three pence to the British government. So pinkies up, and cheers!