Talk of the Town

If you’re not on with Eagan and Braude, you’re no one in this city. How WGBH’s dynamic radio duo became the only voices that matter.

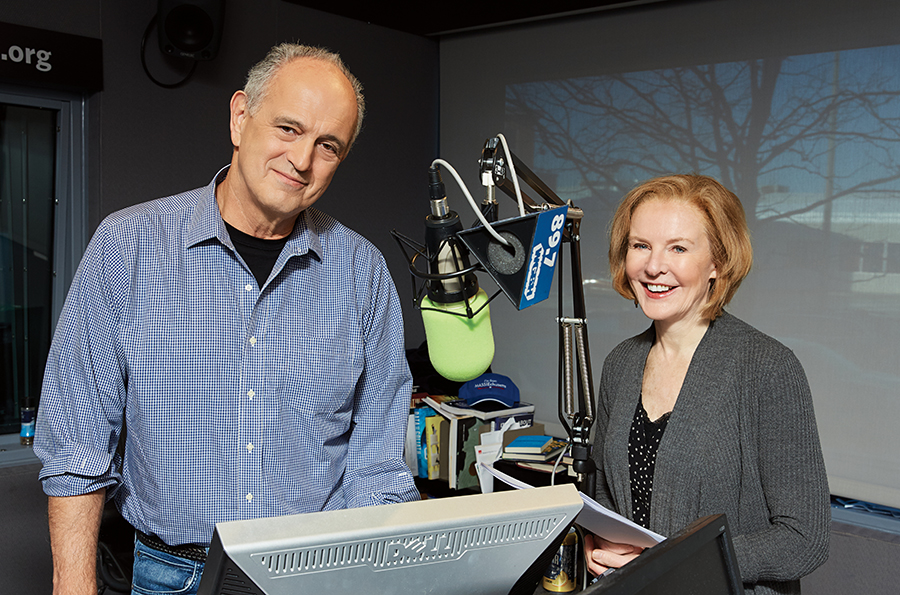

Photograph by David Yellen

One Friday afternoon in December, the Boston Globe published an account of sexual harassment taking place within its hallowed walls. The article detailed inappropriate advances by three former employees, but declined to name them. A swarm of angry critics promptly leapt down Globe editor Brian McGrory’s throat. In the days that followed, McGrory declined to address the controversy and didn’t agree to any interviews. The first chance anyone had to confront him came during his regular Wednesday appearance on Jim Braude and Margery Eagan’s WGBH show, Boston Public Radio. For anyone following workplace harassment scandals in Boston, the interview was appointment listening.

Most weeks, Eagan and Braude’s conversation with McGrory is chummy. That week, it wasn’t. “Why didn’t you disclose the name of the contract worker, the reporter, the sales guy, who are no longer with the Globe?” Braude pressed. “Why didn’t you disclose the names, Brian?” Eagan jumped in next, citing critics who accused the Globe—the newspaper that broke open the Catholic sex abuse scandal—of hypocrisy. “Answer those people,” she said.

For a while, McGrory acquitted himself fine, until Braude, like some public radio Poirot, asked a dagger of a final question. Had the Globe consulted the female accusers before letting their alleged harassers go unnamed? “I assume that Mark, uh, did his due reporting,” McGrory sputtered, referring to Mark Arsenault, the journalist who wrote the story. “And in the course of his reporting I assume he talked to as many people as he could. But uh—I’ll leave it at that.”

Suddenly, Eagan and Braude had given the story new life. The next morning, WEEI’s Kirk & Callahan sports radio show opened with a sound bite of Braude grilling McGrory, before savaging the Globe over the next several hours. Criticism escalated until McGrory released a page 1 mea culpa, apologizing for not disclosing the names.

It’s not just the editor of the Globe who has to come kiss the ring—and occasionally be taken to task. Every month, the biggest names in the state—Mayor Marty Walsh, Governor Charlie Baker, Attorney General Maura Healey, Police Commissioner Bill Evans—appear in studio for hourlong sessions. It’s the only regular forum in which local pols cannot dodge questions; whatever they say on air each month tends to make the news. In fact, the hours of auditory real estate occupied by Braude and Eagan are arguably the most important in all of Boston broadcasting; they’re the place where anyone who is, or wants to be, somebody must make an appearance. And that influence extends beyond radio. Eagan writes a weekly Globe column. Braude hosts WGBH’s influential nightly TV show, Greater Boston. During last fall’s mayoral election, there was only one televised debate; Braude and Eagan moderated it.

Their supremacy was won gradually, and there is some question as to how it happened. One possibility: They’re genius broadcasters who have located a sweet spot between highbrow commentary and blue-collar banter, and combined it with dynamite on-air chemistry of the Joe-Mika/Natalie-Chet variety. Another possibility: In Boston’s decimated local media landscape, it isn’t hard to attract an audience. The very day the Globe published its harassment story, the Boston Herald declared bankruptcy and rival radio hegemon Tom Ashbrook of WBUR was suspended due to workplace misconduct allegations. Left to survey—and comment upon—the wreckage are Braude and Eagan. “Jim and Margery,” declares Globe columnist and friend of the show Alex Beam, “are the king and queen of the broadcast dung heap.” Braude himself subscribes to a somewhat loftier version of this thesis. “There are no churches, unions, social clubs, whatever,” he theorizes. “It’s all disappeared. So, with the social infrastructure gone, we, to a degree, are the social infrastructure.”

It’s the sort of grandiloquent thing Braude might say on the air—and Eagan might mock him for saying. Still, he’s probably not wrong. In this town, they’ve got the last word.

Jim Braude and Margery Eagan broadcast most weekdays from a first-floor studio in WGBH’s unmissable Brighton edifice, off the Mass. Pike. Their show runs daily from 11 a.m. to 2 p.m. The windows of their studio offer a view of the New Balance factory outlet to the south and the Stockyard restaurant to the north. The first time I sit in, it’s the Thursday before Thanksgiving. I don’t know when they arrived that morning, but when I get there at 9:45 their workspace is littered with tiny water bottles and printed-out articles from the New York Times and Washington Post, suggesting extended prep work prior to my arrival.

Braude, 68, is standing stage right, wearing jeans and an untucked pink dress shirt with a small tear in the elbow. He is staring out the window, eating a yogurt. Eagan, 63, is dressed in an olive cardigan over an olive T-shirt. She is bouncing on the balls of her feet, reading silently from one of the printouts. They will remain standing throughout the show. Eagan offers to get me a doughnut from the control room, where three producers and one sound engineer sit, visible to the two hosts through another glass window. “He can get his own fuckin’ doughnut,” Braude says, rolling his eyes. “Oh, Jim,” it occurs to Eagan at that moment, “why don’t you point out to Simon all your little Tupperware containers, these little neurotic Tupperware containers?” The vibe is good. We settle in.

Margery Eagan fields questions from her cohost on his TV show, Greater Boston

Each day, the show is divided into three component parts. There are “talkers,” in which Jim and Margery take calls from listeners. There are interviews with weekly or monthly guests, such as McGrory or Beam or Walsh. Then there are interviews with one-off guests who are in the news, or peddling books, or generally compelling to talk to. The show oscillates between local and national material, with emphasis on whatever’s leading the headlines. Today, the top local story concerns a possible ticket-fixing scheme involving a state judge and the former head of the state police. The national story is the still-gestating Republican tax plan, which Eagan and Braude find loathsome. Events on Capitol Hill conspire, however, to tilt the show’s emphasis toward the familiar and dismal topic of workplace sexual harassment.

A little after 10:30 a.m., a producer, Tori Bedford, says something into Jim’s and Margery’s headsets. Margery looks up.

“Oh, shit,” she says.

“Oh, my God,” Braude says.

“Al Franken’s a groper,” Eagan elaborates.

“Oy vey,” Braude says.

There are two televisions in the studio, one tuned to New England Cable News, the other to CNN. The one playing CNN will soon devote itself to Franken. With 20 minutes left before they go live, Braude tries to refocus show prep on their forthcoming interview with Massachusetts Congressman Michael Capuano, during which they are to discuss the tax bill.

“I think we should ask him about sex harassment,” Eagan says, sensibly.

Braude considers. “He lived with Anthony Weiner. Or they were just really good friends. I can’t remember.” He shouts to the control room, seeking an answer.

“I hope Capuano’s not a sex harasser,” Eagan murmurs.

Bedford chimes in with confirmation that Capuano and Weiner were roommates for many years. Braude and Eagan start cracking up. Braude pounds the table, still laughing, then attempts to corral the situation. “You know, you can’t laugh when talking about Anthony Weiner to Capuano, Margery. Okay? Can you control yourself? Or can’t you?”

“Because he’s very fond of him?”

“No! Because he fucking sent his penis picture to a 15-year-old!”

“I know. Okay. Right.”

Braude and Eagan have perfected a fast-paced, ironical patter that—outside of Car Talk, which no longer broadcasts—is virtually never heard on public radio. The effect is more Aaron Sorkin than All Things Considered. At the same time, they are too smart, and ’GBH is too NPR, for the show to devolve into Morning Zoo vulgarity. At times, as in the McGrory interview, guest segments are the main event. More often, they provide context for Eagan and Braude’s repartee—a bassline over which the two hosts can improvise. They aren’t perfect. Braude interrupts Eagan too much. Eagan trips over her words. But perfect doesn’t make for good radio.

At 10 minutes to 11, they have moved on to Leonardo da Vinci, about whom one of today’s guests, Walter Isaacson, has written a book.

“All the things about him should be together,” Braude says, planning the interview. “Illegitimate was a huge thing. Gay. Vegetarian. The procrastinator thing, I love.”

“And the thing about the Mona Lisa,” Eagan says. “That he worked on it until he died.”

“Sixteen years.”

“Did you know that? I didn’t know that.”

“No, I didn’t know.”

“And that he carried it around over mountains and stuff?”

“Mona Lisa sucks.”

At four minutes to, the photo of Franken shows up on CNN. Braude’s incredulous. “His hands are on her fuckin’ breasts in this picture! Oh, my God.” They’re about to go live and he’s still bugging out. “I just looked at it again. That is unfucking—oh, my God. Here we go.”

The show begins.

“He’s Jim Braude, I’m Margery Eagan. You’re listening to Boston Public Radio, 89.7 WGBH. Good morning, Jim.”

“How are you, Margery?”

“…I’m fine.”

She doesn’t sound it. “You’ll hear why she’s a little stressed today in a minute.”

Margery motions to speak.

“Al Franken is now a sexual abuser, too, apparently,” she says.

“Alleged,” Braude clarifies. “Though the photograph was not helpful.”

And they’re off.

In 1990, Margery Eagan wrote a column mocking Jim Braude. He was a voluble left-wing political gadfly. She was a rising star at the Boston Herald. This seems strange now, but at the time the entire state was consumed by a deeply wonky debate about a proposed tax cut. Pushing the measure was Grover Norquist’s spiritual godmother, Barbara Anderson, a suburban housewife turned anti-tax zealot. Against her was Braude, a former labor organizer from Cambridge whose advocacy group, Tax Equity Alliance for Massachusetts (TEAM), existed to defend the good name of revenue collection. He and Anderson toured the state, often sharing a car, publicly debating each other.

“There’s Gentleman Jim,” Eagan wrote. “So smooth, so eloquent, exuding noblesse oblige in his rumpled blazers, like the heartthrob of freshmen girls in Econ 101. He’s already the heartthrob of the pro-Sandinista left. Can’t you just imagine him in a battered ‘Save the Whales’ Volvo, sneaking off to Crate & Barrel at The Mall at Chestnut Hill.”

Eagan wasn’t conservative. For the Herald, she was probably left-wing. But the paper’s waste-fraud-and-corruption preoccupation meshed nicely with her innate suspicion of liberal pieties. She grew up in Fall River. Her father was a traveling salesman for Firestone tires, her mother a pianist who performed around the region with local musicians. “I saw people, my neighbors and my family, that couldn’t afford to stay in their houses, which were worth $10,000, because the property taxes were three grand,” she says. “I had a much more cynical attitude about the government than [Jim] did. If you raise everybody’s taxes and the government’s going to take care of everybody, then they’re going to hire more of their brother-in-laws.” Eagan enrolled at Smith College, transferred to Stanford, and graduated in 1976. In 1981, she took a general assignment job at the Herald. Shortly after that, when Howie Carr left the paper for a TV gig, she filled his slot and landed her first regular column.

Eagan’s investigative skill made her a dual threat. She made her name during the 1990s, reporting egregious misconduct by caseworkers at the Massachusetts Department of Children and Families. At the same time, the paper took advantage of her broad range and sharp wit by siccing her on big national political stories. Her acid coverage of Clinton-era shenanigans made her Boston’s answer to another gimlet-eyed, Irish-Catholic columnist—the New York Times’s Maureen Dowd.

Over time, though, the Herald became a reputational drag. She and her then-husband, Peter Mancusi, a Globe journalist, raised three children in a Brookline condo. “The lady across the street invited us to dinner and asked Peter what he did,” Eagan says. “He said he was on the Spotlight team. Oh, my goodness, Boston Globe, and wasn’t that swell. Then she asked me what I did and I said, ‘Well, I work for the Boston Herald.’ And she said something almost exactly like this: ‘Oh, how difficult that must be for you, dear.’” (Eagan and Mancusi divorced in 1999.) Meanwhile, as the Herald began its slow decline into obsolescence, its brand-name writers began jumping into broadcasting. “The thing that became kind of the way out, the brass ring at the Herald, was getting the radio gig,” says Eagan’s former colleague Kevin Convey, now the chair of Quinnipiac University’s journalism department. Eagan began formulating a plan B.

Jim Braude first hit the scene in the 1990s debating Barbara Anderson over tax policy. / Courtesy of Jim Braude

Braude, an only child, grew up in an entirely different middle-class milieu. His mother raised him alone in Center City Philadelphia, juggling several office jobs at once. He paid his way through college at Penn and law school at NYU, then became a housing- and prisoner’s-rights lawyer—and later, a labor organizer—in the South Bronx during the city’s Escape from New York era. (“It looked like Berlin after the war,” he says.)

Through union circles, Braude met his wife, Kristine Rondeau, a Cambridge labor organizer, and moved to Massachusetts. (They have two daughters.) He spent a decade doing battle with Barbara Anderson, and then served a two-year stint on the Cambridge City Council. The work was low-octane; the only accomplishment Braude mentions to me concerns a tree. “I think there was a tree in mid-Cambridge going to get cut down,” says former Cambridge mayor Anthony Galluccio. (It was a tulip tree. Braude threatened to chain himself to it in protest.) “He was possessed by keeping that tree up.” Other than that, Galluccio says, “I think he was disappointed in the pace pretty early.”

In the ’90s, NECN, a brand-new, all-news television channel with an appetite for policy, began inviting Braude and Anderson to perform their act on air. The dynamic didn’t take, but NECN kept Braude on during weekends, pairing him with a constellation of cohosts, including Eagan. Eagan eventually left, while Braude stayed on to host the channel’s nightly news analysis show, at first with former Channel 5 heavy Chet Curtis in 2002, then on his own until 2015.

But Eagan and Braude’s stint in cable news obscurity wound up being a test-run. In 1999, radio station WTKK debuted an all-talk, mostly right-wing format. Eagan was hired first, but every male cohost she was paired with failed miserably, until Braude came aboard. From the start, Braude played the dry-witted liberal scold; Eagan was his populist foil with a built-in bullshit detector. For more than a decade, they outlasted ratings duds and self-immolating conservatives, including Don Imus, of “nappy-headed hos” infamy, and local screamer Jay Severin, who bragged about bedding interns. Until, on December 29, 2012, the station converted to hip-hop and fired all of its hosts.

At the same time, a transformation was also under way at WGBH radio. In 2009, the station moved from classical and Celtic music to news. Already the country’s most prominent public television producer—Masterpiece, Nova, Frontline—’GBH decided to make a play for local radio. It was a risky move. Boston’s all-news WBUR was a stalwart NPR syndicator in its own right. Boston’s a nerd town, but asking people to support two public radio stations was a lot. In different hands, ’GBH might have tried to out-’BUR ’BUR by programming cerebral, nationally focused talk against homegrown stars Tom Ashbrook and Robin Young. But the metamorphosis was led by Phil Redo— longtime boss at ’TKK.

When ’TKK went “urban contemporary,” Redo asked Braude and Eagan to try out for ’GBH’s midday slot, which was then held by mainstays Emily Rooney and Callie Crossley. By early February, they were hired. “When they first came here, it sort of felt like an arranged marriage,” says Chelsea Merz, the show’s senior producer. The drive-time mentality didn’t make any sense to the newsroom. “They wanted to interview Mike Tyson on his cell phone.” Not long after they were hired, Braude recalls, philanthropist and Chinatown grandee Helen Chin wrote a letter to ’GBH president Jonathan Abbott telling him their hire was the worst decision in the history of the station. Death threats from Weston weren’t far off, presumably.

Ratings healed all wounds. The year before Braude and Eagan took over the show, according to Nielsen, it was averaging 5,400 listeners at any given moment. In their first year, they doubled that number. In 2014, competing against Young’s Here and Now, they passed WBUR head-to-head for the first time. By 2017, BPR was averaging close to 27,000 listeners. They weren’t just beating up on WBUR and right-wing WRKO, but also on sports-radio monsters WEEI and 98.5 The Sports Hub. In their time slot, Braude and Eagan were the most popular talk-show hosts in Boston.

There’s no science behind Eagan and Braude’s formula. But there is a specific reason it works. For decades, the history of talk radio in Boston was the history of people like them: erudite but accessible, political but non-dogmatic—people who could hold a conversation about whatever for three hours a day. Jerry Williams, a longtime WRKO presence, was the proverbial dean of the corps; David Brudnoy, of WBZ, his successor. Public radio personage Christopher Lydon has always been a bit more wine-and-cheese, but basically cut from the same cloth. Dozens of mostly forgotten hosts—hello, Marjorie Clapprood—have been players in their time, too.

Why does this matter? It made for good radio and didn’t turn people into frothing, clannish partisans. “In the Jerry Williams era, it was more geared to populism,” says Michael Harrison, the longtime publisher of Talkers magazine, a radio trade publication based in Longmeadow. “Talk-show hosts were fascinating, unique individuals who didn’t preach to target audiences. It wasn’t left-right or Republican-Democrat as much as the big guys versus, us, the little guys.”

Why did that change? The usual reasons. “Starting with the Telecommunications Act of 1996,” says local media encyclopedia Dan Kennedy, of Northeastern University, “any meaningful restriction on the ownership of radio stations went out the window. So, you had massive corporate conglomerates buying up radio stations all over the country.” Which means that over the past two decades, Kennedy says, we’ve seen the “absolute disappearance of a certain kind of [local] commercial radio program that people used to like.”

Boston’s lackluster broadcast scene reflects this. Howie Carr’s show is syndicated and doesn’t cover anything local. In November, his station, WRKO, was bought by conservative-leaning conglomerate iHeartMedia (formerly Clear Channel Communications). Conservative-but-sane WBZ host Dan Rea has been relegated to an undesirable 8 p.m. slot, and iHeartMedia also recently bought his station. WBUR will never be bought by iHeart, but it produces only one hourly local show a day, Radio Boston. The TV situation isn’t much more dynamic. “If you put my feet to the fire, I can’t name the anchorpeople for the 6 o’clock news,” says ’GBH’s Rooney, who has worked her entire career in local television. Carr doesn’t have an opinion about his local competition either. “I don’t know,” he says. “I can’t really comment on this. I listen to Rush Limbaugh.”

The obvious lesson here is that local coverage gets listeners. “One reason sports radio does so well is it deals with mega passions with local teams,” Harrison says. And the moral of the story for other public stations is to emulate old-school commercial talk, and loosen their collars. “I don’t particularly like public radio,” Beam, of the Globe, says. “I like Jim and Margery because they’re not public radio-y. I hate that kind of Wellesley College, soft-toned, Oh you know, we’re in the vapors over Trump.” Even at ’GBH, the most common praise you’ll hear for the show is that it doesn’t sound like NPR. “Think of what public radio was when it started,” says Merz. “It wasn’t pompous or self-righteous. It was community-oriented. I think they’re bringing public radio back to that.”

Braude and Eagan have perfected a fast-paced, ironical patter seldom heard on NPR. / Photograph by David Yellen

If the show’s success made stars of Braude and Eagan, it made Braude, in particular, a power broker at ’GBH. In 2015, he was tapped to anchor the station’s 7 p.m. news show, Greater Boston, after Rooney, the longtime host, stepped down. At the time, ’GBH’s managing director for news was a commercial TV veteran named Ted Canova. The Canova era, according to five sources in the ’GBH newsroom, wasn’t pleasant. He had a reputation for being a bully and made his colleagues miserable. “It was common knowledge around the newsroom that Jim had no respect for Ted,” says one staffer. When Braude was offered the Greater Boston job, say ’GBH sources, he confronted Redo with an ultimatum: He wouldn’t accept if Canova was still employed at the station. Canova was promptly let go. (Redo disputes that it was an ultimatum, telling me he came to the decision on his own. Canova did not respond to interview requests.)

That wasn’t the only time Braude flexed his muscle. In 2017, ’GBH hired a former WBZ-TV meteorologist named Mish Michaels as a science correspondent for Greater Boston. When Braude learned she had dabbled in anti-vaxxer trutherism, he complained to Redo and the show’s executive producer, Bob Dumas. They agreed to let her go, and Braude broke the news to the Globe. (Michaels released a statement saying her views had been “positioned inaccurately.”) In 2016, Braude made $364,000, a salary that reflects not only the two shows he hosts, but the de facto executive power he wields. (Eagan’s salary was not high enough to be listed on ’GBH’s public tax documents, but a ’GBH source says it’s equivalent to Braude’s radio salary.)

In its own way, though, this power carries a danger. Lacking any competition—inside and outside of WGBH—Braude and Eagan have settled into a comfort zone that can border on complacency. Roughly half of the show’s guests appear on a weekly or biweekly basis. In theory, they exist to provide local perspectives in their areas of expertise. But what they really do is make the show more parochial. The show’s national security expert, Juliette Kayyem, who served in Obama’s Department of Homeland Security and currently lectures at the Harvard Kennedy School of Government, is credentialed enough. But as news changes each week, her insights tend to stay the same. John King, an anodyne CNN personality best known for swiping giant touchscreens on television, is touted as a Dorchester native, as if that lent value to his political punditry.

When it comes to bigger-ticket guests, there’s a different problem. Interrogations do not necessarily make for great radio, and Braude and Eagan aren’t always great about grilling public figures. “Those interviews with the mayor, the governor, and the police commissioner are absolutely dangerous,” says Dig Boston editor Chris Faraone, a persistent Jim Braude Twitter troll. “With Commissioner Evans, it’s a real hero worship. He knows it’s a forum where he can say anything.” (“I probably shouldn’t say this,” Braude confesses, “but I love Evans.”) But even this complaint says something about Eagan and Braude’s outsize role in the city’s media ecosystem—nowhere else would a pair of talk-show hosts be expected to double as ball-busting muckrakers. On balance, if you’re letting two strangers into your lives for three hours a day, it’s probably best that they don’t yell the whole time. And if what they’re selling is personality, it makes sense to let them be themselves.

The Sunday after my studio visit, Eagan and I attended a 60-minute hot yoga session at a studio in Brookline. Hot yoga is pretty much the same as yoga, but in a hot room. Eagan does it three times a week. I had never performed a downward or upward dog in my life. You get the picture. This was in part a narrative gimmick, undertaken in the style of a celebrity profile. But I was also wondering to what extent Braude’s and Eagan’s on-air personalities were part of an act. The day before, Braude and I had hung out at a coffee shop in Cambridge. Now I’d meet Eagan on her own turf.

A number of people told me Eagan and Braude behave the same way outside the studio as they do when they’re broadcasting. But that’s the case only when they’re together. On air, they knowingly play off a familiar gender trope: Jim as imperious mansplainer, Margery as flighty and effervescent charmer. Eagan isn’t bothered by Braude’s logorrhea—“He knows he does it. He apologizes for it. He says, ‘I’ll stop.’ And he just can’t stop.” And it probably adds some useful tension to the show. But it also obscures some of the more winning aspects of Eagan’s personality.

On her own, she blooms. Her words tumble out, to the point where it’s unclear if she’s interrogating me or herself. An inner monologue, broadcast out loud. She spitballs half-formed column ideas as they come to her, and doesn’t bother putting risqué declarations off the record. As we drive to the studio in her hybrid SUV (Braude’s got the same one), Eagan mentions that hot yoga replaced jogging as her anxiety cure. “Everybody’s different,” she muses. “I had to run a long way, at least five or six miles, before I found it helped. But I mean, there’s a million other ways to do it, I’m sure. Drugs.” After yoga, she invites me back to her house to change. When she realizes the radio is on in her bathroom, she shouts from another floor that she hopes it isn’t tuned to ’BUR. (It’s tuned to ’GBH.)

Conversely, Braude is less himself when Eagan’s not around. In conversation, he’ll catch himself rambling, then stop abruptly, betraying some insecurity not evident on the air. Braude says it spooks him to walk into public events without Eagan at his side. Eagan swears that once they’re inside, he’s mobbed by fans and promptly abandons her. Both are probably true. “I think Jim needs an audience, and one person is probably not enough,” says a source close to him. “He says this stuff about how it gives him hives to go to parties. I think he actually needs the feedback more than she does.”

Overall, the one-on-one sessions are disorienting. It feels like they’re on with a guest host—me—and the show’s just not as good. When the three of us meet for dinner later that day at Myers + Chang, in the South End, the familiar dynamic returns. We order our drinks, and I begin scribbling something in my notebook. Braude looks across the table and asks what I’m writing. I tell him I’m describing what he’s wearing, which is a ratty Champion sweatshirt. “He looks very fetching,” Eagan snarks. Braude begins to stress because he doesn’t like name brands: “I wear nothing with insignias on it. Have you ever seen me wear anything with insignias?”

Looking closer now, I notice Braude appears a little worse for wear. He explains he couldn’t sleep the night before, so he flicked on WBZ radio in the wee hours and stared at the ceiling. “This is too humiliating to admit, but I had ’BZ on and somebody was interviewing two guys—this is really humiliating—who had written a book about Peter Falk. Colombo. Yeah, the title of it was like, Beyond Colombo, as embarrassing as it was.” Braude, even off air, is a radio obsessive. The decimated state of the industry bewilders him. “When I moved here—I’m making up a number—there were like 15 talk-radio shows. There used to be five or six or seven television talk shows. When’s Jon Keller’s show? Five-thirty a.m. Sunday morning?”

“I think so, something like that,” Eagan says.

(Keller does not, in fact, have his own show, but his commentaries run Sunday mornings at 8:35 a.m. on WBZ-TV.)

I ask how they plan to fill such gaps in the broadcast landscape while still catering to ’GBH’s upwardly mobile audience and donor base.

“We get a lot of calls from Roxbury, actually,” Eagan says.

“Because there’s nothing else on.”

Braude literally doubles over in laughter. A consensus is reached that this would make a good slogan. We order dessert. Eagan asks if I can expense it. Of course, Braude answers. “He’s writing about Eagan and Braude—There’s Nothing Else On.” An attempt is made to determine if, in fact, anything else is on. “Oh, God, I don’t watch the local news anymore,” Eagan says. “I shouldn’t say that.” Braude waits a beat. “Braude and Eagan—There’s Nothing Else On!”

Margery cracks a smile. Jim laughs at his own joke. It’s funny because it’s true.