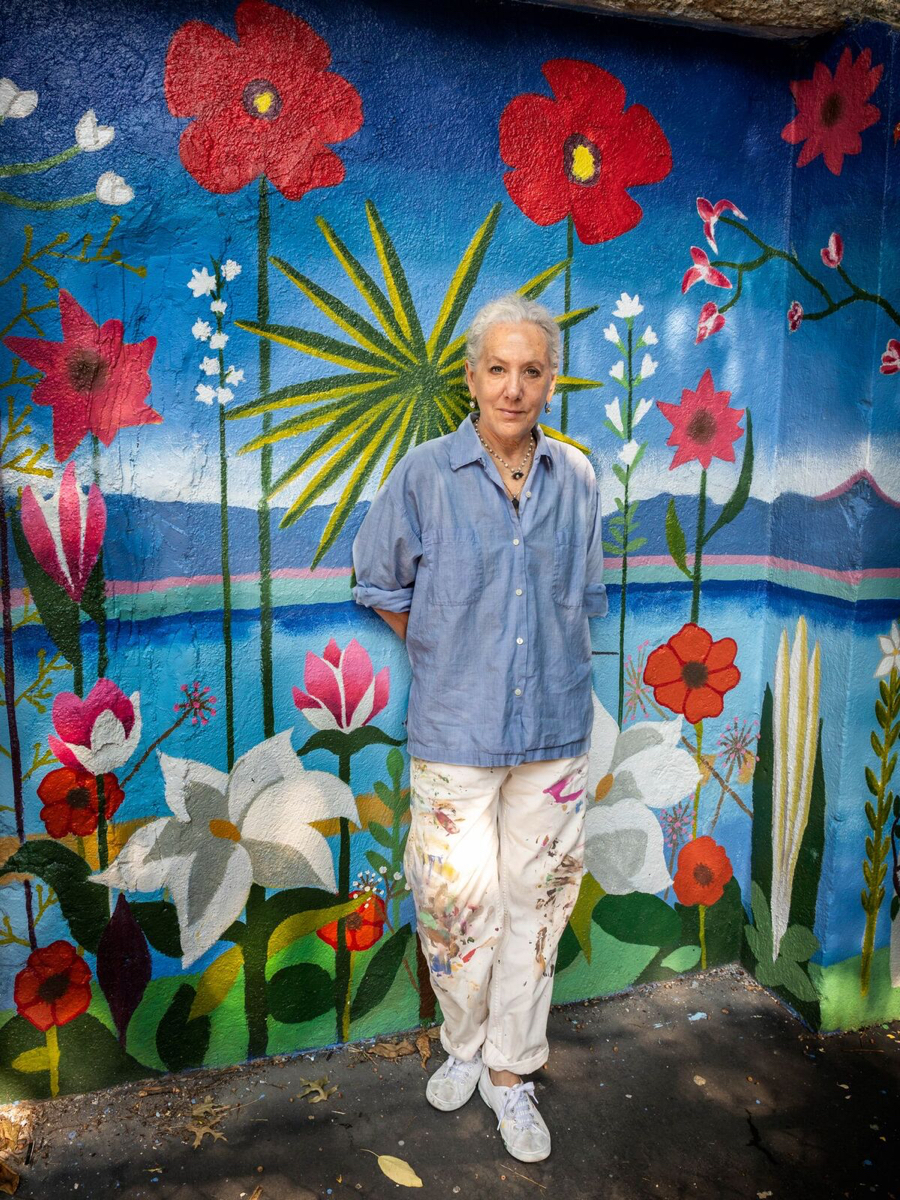

I Love My Job: The Mayor’s Mural Crew Gives Boston an Artistic Makeover

Since Heidi Schork founded it 27 years ago, the program has made the city a more colorful place.

Photo by Eric Clark

What’s it like to have one of the coolest jobs in Boston? We want to know. So we’re tracking down the city’s most interesting people and asking them the questions that need answering.

If you’ve ever come across a splash of color on a once-abandoned wall in Boston, there’s a very good chance you have Heidi Schork to thank. As the first and only director of the Mayor’s Mural Crew, she and groups of Boston high schoolers have been sprucing up corners of the city for nearly three decades.

Since Mayor Ray Flynn recruited her in the early 1990s to help cover up graffiti, Schork and her team have brought scores of outdoor murals to life, while also taking on projects like beautifying local school cafeterias and leading artistic outreach at a women’s shelter.

Schork’s program, run by the city’s Division of Youth Engagement, gives the 15-18 Boston Public Schools students lucky enough to work with her each year both a paid gig for the summer and an outlet to express themselves artistically. It’s not a bad first job, and it’s a pretty good deal for the rest of us, too. Before this season’s painting schedule wraps up and the teens head back to school, we caught up with Schork to find out more about the woman who makes the city her canvas.

How did Boston end up with a city-sanctioned Mural Crew, and how did you end up in charge?

It was a serendipitous series of events. Around 1990, I was managing a little retail store on Brookline Avenue called Last Minute Travel. It was one of the first discount travel stores where you could buy a plane ticket or package deal somewhere, for tomorrow. We had a big whiteboard and every week I’d change it to reflect whatever we had going at the moment. “$199 to Jamaica, airfare and hotel included!” and I’d [draw] a whole scene of Jamaica. Or “Cancun for $159!” And I’d do Mayan ruins. I was constantly updating it.

One of my clients was mural artist [and Boston Public Schools artist-in-residence] Roberto Chao, and he saw the work I’d been doing. He said to me, “You are a mural painter.” And I said, “Oh, I wish.” He invited me to work with him on a project with a group of kids called the X-Men in Egleston Square. Instantly, I loved it. This is what I want to do. Then he got a call from the Parks Department and they said, ‘We’re looking for a mural painter to cover gang graffiti, can you recommend someone?’ And he said, ‘Yes. Call Heidi.’

At that time, youth employment opportunities in the city were quite boring. They were menial labor in vacant lots, weed-whacking and picking up litter. There was really no other option other than that. So I was asked to come in and talk about doing murals, and that was that. In the ensuing years, we’ve done hundreds and hundreds of projects, and the possibilities are endless. I have a million ideas that I want to do and not enough time.

The Mayor’s Mural Crew hard at work on their latest project in Cutillo Park in the North End | Photo by Eric Clark

So who decides what you and the teens paint?

Most of the time I’m the source of the ideas, but we do work as a team. We look at the history of a neighborhood or the architecture, the light. Who lives there? What are their stories? We try to put our finger on the pulse with careful observation and just walking around and paying attention, taking lots of photos. Every single device I own is out of storage. I’m inspired endlessly.

Tell me about the crew. Do you have any memories of your time with them that stick with you?

There are hundreds of those stories, my dear. Every day is something new. I want the kids who work for us to have their summer job be lighthearted and fun and also feel a sense of accomplishment. I believe there are big lessons to be learned, like how to accept criticism: ‘That hand looks like a mitten. Fix it.’ And to be able to say, ‘You did this! You worked hard for this!’ No matter what the kids go on to do later in life they’ll have started out with that kind of training.

I’m still in touch with probably a couple hundred of them via Facebook, and quite a few of them have gone on to have art, or art-related careers. There are also quite a few kids who have had tough times in the world. Through the city we also connect kids with other resources they might not know about for health, housing, school issues. My job is a little bit more than just being an artist.

Photo by Eric Clark

What makes a good artist? How do you spot one?

It’s more than just being able to draw, of course. Hundreds of kids come in for interviews with artwork and sometimes it’s one piece of paper with a drawing in ballpoint pen that was clearly done on the T. Other times it’s a massive portfolio, years of work. But you just have to observe the world around you and pay attention and start to notice things that other people don’t notice.

What’s the worst place to put a mural?

Brick. I don’t often paint on venerable old brick. I don’t want to cover it all up. We don’t have a lot of the old, classic kiln-fired brick in Boston anymore, so I tend to stay away from it. It’s also the worst surface to paint on. Cinderblock and stucco are fab. Plywood is OK. A building that’s been boarded up with plywood and has a little frame around it is great. Or corners of older buildings with fenestrations that might have been plate glass windows at one time but they’ve been filled with masonry. Those are great, great locations.

Is there anywhere in the city you’re dying to paint?

Dewey Square! We’ve never been asked to do Dewey Square [which is host to a giant mural wall that is updated annually] and every time we drive by it we look at it with lust. I would love to get my hands on Dewey Square.

What’s the difference between art and graffiti, to you?

That’s a tough question. It’s in the eye of the beholder. Fortunately it’s rare, but some of our murals have been tagged, and that’s when someone writes their name on our murals in Sharpie. That’s irritating to me. I would never think of doing that. I know small businesses don’t want someone’s name on the side of their little business. But then there are more of what I’d say are carefully done spray painted pieces that have been thought out. Those are murals.

This mural, at the corner of Centre Street and Seavern Avenue in Jamaica Plain, is one of Schork’s favorites. | Photo by Eric Clark

Are vandals just artists that haven’t been discovered yet?

No. I think there are just people who like to write their names everywhere. I don’t know that their intention is to make art. I can’t see it. I’ve seen statues and monuments in the city that have been spray-painted. It’s like, why would you do this? For a while it was cool to subvert advertising by altering a word or changing it in some way and I thought that was kind of interesting. That was more considered.

What’s your favorite color?

Blue. Yves Klein Blue. It reappears constantly in my work. And the color of Frida Kahlo’s house in Mexico City. That blue, too. I spent a number of years in Mexico and went to university there. There’s a new blue that’s just been discovered, too. I don’t know if discovered is the word, but it’s got a little more indigo. It’s beautiful.

What would you change about Boston if you could?

I would like us to hold on to our charm. Roslindale doesn’t look like JP and JP doesn’t look like Mission Hill, even though they’re right next to each other. That sense of place I find is disappearing.

So if you could change something, you’d slow down all the changes.

Yes. I hope we pay attention to our Boston-ness. Sometimes I just turn a corner in the city and my breath is taken away by the vista.

In your own way, you’re changing the city, but you’re adding instead of subtracting from its uniqueness.

That’s my intention, to create a breathtaking moment for someone else.

Photo by Eric Clark