A Case Against Steve Wynn: The Anatomy of a #MeToo Accusation Gone Wrong

How dozens of newspapers published an improbable claim against casino magnate Steve Wynn.

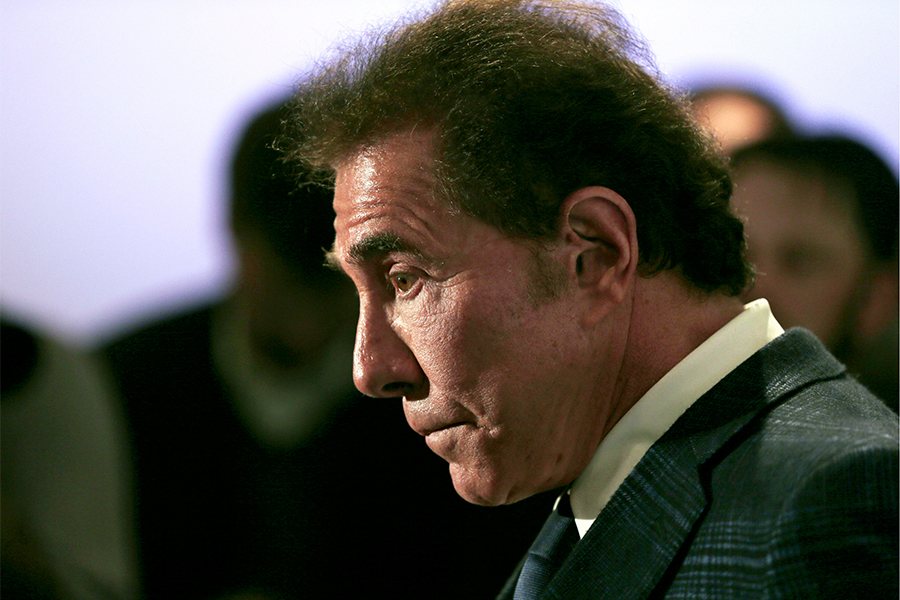

Photo via AP/Charles Krupa, File

On February 27, the Boston Globe published an article under the explosive headline “Woman tells police she had a child with Steve Wynn after he raped her.” The Associated Press, America’s largest and most trusted news agency, had produced the piece. But in this particular case, less than a day’s worth of reporting had gone into vetting the accusation in the headline, which came from a single, partially redacted police report. Still, within hours, the story started making waves. Along with the Globe, at least 100 other publications, including the New York Times, republished the AP’s article. Now, however, Wynn’s accuser is speaking out and new information casts serious doubt on the validity of her claims against the casino mogul.

By the time the AP story hit the newswires, Wynn had already been the subject of a deeply reported, damning account in the Wall Street Journal detailing his decades-long pattern of sexual harassment and assault. The native New Englander had already stepped down as the finance chairman of the Republican National Committee and as the CEO of Wynn Resorts, his casino company. But the new allegation reported by the AP had ripple effects in Massachusetts, where Wynn Resorts is building the now $2.5 billion Wynn Boston Harbor casino in Everett (since renamed Encore Boston Harbor).

In fact, the day after the AP’s story ran, local politicians made strong remarks about Wynn. “It’s clear to me,” Attorney General Maura Healey said at the time, that “if what’s being alleged is true … the casino cannot bear Wynn’s name.” Massachusetts politicians had already strongly condemned Wynn, says longtime Massachusetts political analyst Jon Keller, “but clearly a sensational rape allegation on top of what had already occurred cemented the dynamic.”

Since then, the AP article has become the subject of a defamation lawsuit filed by Wynn, alleging that the details of the accusation were so outlandish that the news agency should have known it was false. And in hindsight, based off of our recent reporting, proper vetting before publication likely would have produced grave doubts about the credibility of the allegation. Instead, the AP rushed to publish an explosive claim. And as a result, the news agency has provided fodder for critics of the #MeToo movement who argue that, in today’s climate, accusations of sexual misconduct are too readily believed.

The AP article differed starkly from other prominent works of journalism that have propelled the #MeToo movement. Reports about Harvey Weinstein in the New York Times, about Charlie Rose in the Washington Post, and about Steve Wynn in the Wall Street Journal were the result of months-long investigations that rested on dozens of interviews, carefully compiled documents, and corroborating statements from third parties. Conversely, the rape allegation in the AP’s February 27 story relied almost entirely on one brief, partially redacted police report that never became the subject of an investigation—reporter Regina Garcia Cano didn’t even know the name of the woman who accused Wynn of rape. (The AP did, however, reach out to Wynn for comment. The story reports that Wynn’s spokesman “declined comment on the latest allegations.”)

“A police report on its face, even without redactions, is a partial story and requires further reporting,” says Derek Kravitz, research editor at ProPublica and a co-author of the report that analyzed the infamous Rolling Stone magazine story that reported on a false accusation of rape. “This is reporting 101. This is an obligation of all reporters, whether investigative or daily beat, to fully explain and provide context for otherwise fairly damning pieces of information.”

The AP did not leave itself much time to carry out its reporting. Two weeks before publishing her story, Garcia Cano read in the Las Vegas Review-Journal that two women had brought new accusations against Wynn to the Las Vegas police. After filing a public records request, Garcia Cano obtained the two new police reports on February 27. Later that same day, her article went live with the accusation that Wynn had repeatedly raped a woman in the 1970s and that the woman had become pregnant and given birth to a girl in a gas station bathroom.

The AP, however, chose not to publish highly unusual details contained in the police report that might have undermined the accusation’s credibility. For instance, one section of the police report relayed the accuser’s account of the purported birth of Wynn’s child in surreal terms. According to the police report, the baby emerged inside a “water bag,” which the accuser opened with her teeth. Inside this “water bag,” the accuser found a purple “doll.” She breathed on the “doll” and “in a short time her cheeks were turning pink and she opened her eyes.”

Had the AP known the accuser’s identity, it might have had even more reason to question the police report’s veracity. Just over five months earlier, the accuser, Halina Kuta, who claims to be a former Wynn Las Vegas employee, had filed a civil lawsuit against Wynn, in which she laid out a vivid conspiracy theory. In her lawsuit, she claimed that in 1993 Wynn plotted to have her murdered. She also claimed that she was the mother of Wynn’s daughter, Kevyn. Later, in an interview with me, Kuta claimed that she gave birth to Kevyn not long after the alleged rapes in 1973.

According to Wynn’s defamation suit, however, Kevyn was actually born in 1967. The court recommended dismissal of Kuta’s lawsuit in March, describing her claim as “a clearly fanciful or delusional scenario.” Kuta’s lawsuit was a matter of public record at the time the AP published its February 27 report. “This is something that came up in the Rolling Stone case,” Kravitz tells me, “where the reporter didn’t go far enough beyond the initial complaint in order to fully vet what happened and to find additional sources of information.” The AP declined to comment and did not respond to detailed questions sent over email. Wynn’s lawyer in the defamation suit didn’t respond to a request for comment.

If the AP had spoken to Kuta, the wire services would have uncovered additional reasons to doubt the claims she made in the police report. In an interview on August 9, Kuta recounted to me a life story full of improbabilities and demonstrably false claims. She said that Pablo Picasso painted her likeness in the late 1950s or early 1960s while visiting her hometown in Poland, resulting in the well-known masterwork Le Rêve. Not long after, she said, Steve Wynn stole Le Rêve from her parents’ home. In truth, Wynn, a prolific art collector, did own Le Rêve once, but he bought it from another collector in 2001 and, in a highly publicized transaction, sold it to hedge fund titan Steven Cohen for $155 million in 2013. Le Rêve was painted in 1932 and depicts Picasso’s mistress, Marie-Thérèse Walter. Kuta also told me that by the time she started working at Wynn Las Vegas in 2005, she had completely forgotten who Wynn was. When she happened to bump into him three years later, she said, all of her memories of Wynn suddenly came back to her—raising the possibility that she first imagined these events at that time.

In April, Wynn attempted to set the record straight about Kuta’s rape claim, suing the AP and Kuta for alleged defamation. Four months later, a Nevada judge ruled in favor of the AP, stating that the original article, which accurately attributed information to an unverified Las Vegas police report, met the legal standard for “fair reporting.” A lawyer for Wynn said he would appeal. Wynn’s lawsuit against Kuta, who has requested DNA testing of Kevyn, remains open.

The very next day, the AP published an article under the headline, “Wynn Accuser Makes Extraordinary Claims in Court Filings,” describing Kuta’s inconsistencies and improbable allegations. The story also raised questions about the information she initially gave to the police about Wynn. As of press time, the AP’s original article about Kuta’s accusation against Wynn remained on the websites of the New York Times, the Los Angeles Times, the Boston Globe, and dozens of other publications. The accusation was also included in articles that still live on the websites of ABC News, Fox News, and numerous other outlets.