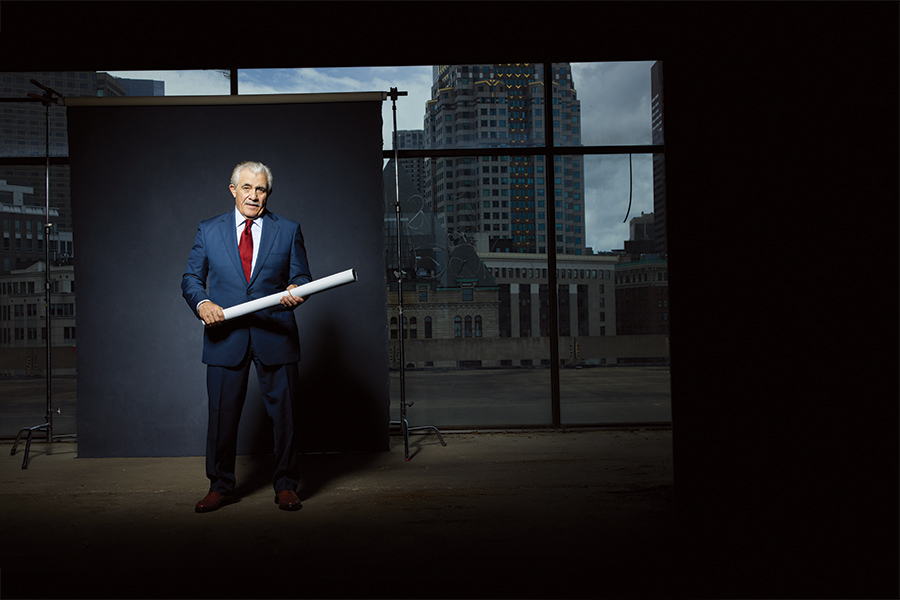

Inside Don Chiofaro’s Long War to Make Boston’s Skyline Taller

After decades of fighting City Hall, Don Chiofaro’s bullish style has made him the most talked-about developer in Boston. But with a friendly mayor now in place and his plan for a soaring waterfront tower in the works, is the town’s toughest builder finally learning to play nice?

Photo by David Yellen

Like all great builders, Don Chiofaro wants to see how high he can go. Rocking on the bow of a harbor ferryboat as the sun sets, he points to the horizon, between Rowes Wharf and the Custom House Tower, and describes the tallest project the Boston waterfront has ever seen. His olive-green baseball cap, atop a full head of white hair and a permanently tan face, displays a single word—“Persistence”—a reminder of how far he’s come, and how long he’s been at war.

A Harvard linebacker turned developer, Chiofaro introduced himself to Boston 35 years ago with carnival flair and kinetic force. He walked into a City Hall meeting wearing his old Harvard jersey and blasting the Rocky III soundtrack. He decimated a parking garage on Super Bowl Sunday 1985. Then he made a TV commercial of the implosion, announcing his plans to build Boston’s tallest building of the ’80s—International Place, a million-plus-square-foot office complex overlooking the Greenway that kicked off a new era in the city’s development. “He liked to be the center of attention,” says Peter Berg, his former classmate and a friend since age 15. Chiofaro’s flair for theatrics even inspired author Tom Wolfe’s linebacker/developer character Charlie Croker, protagonist of his mega-novel A Man in Full. Now, at 72, Chiofaro wants to build the sequel to his signature achievement and cement his legacy in this town forever.

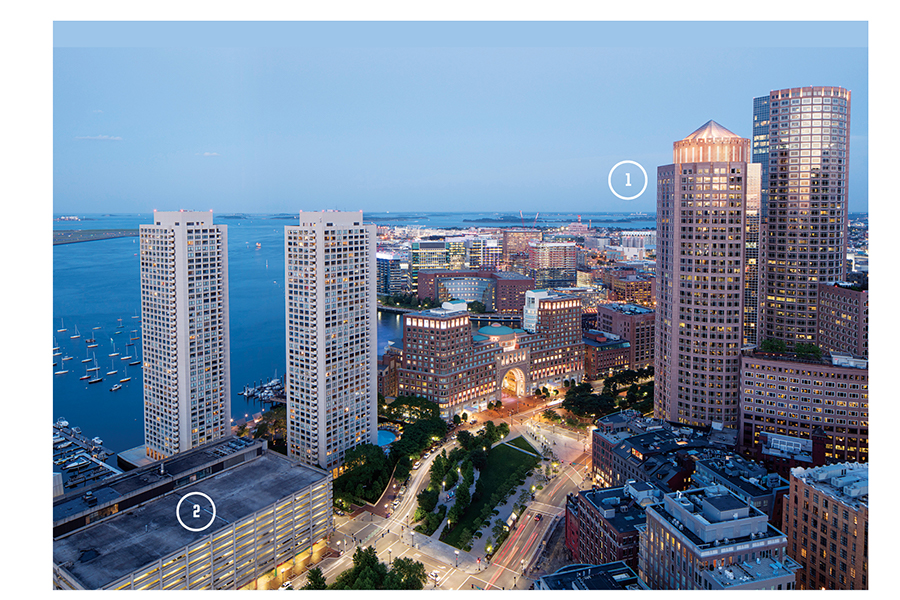

When the ferry docks, Chiofaro strides off the boat along Long Wharf, past the buzzing, boozing crowd at the open-air bar. Fifty years after his last football season, he’s still solid yet quick, a bundle of coiled energy. He crosses between the New England Aquarium and Legal Sea Foods to reach the Harbor Garage, the seven-story concrete monstrosity he bought for $153 million in 2007. His vision is to turn the parking garage into a soaring $1.3 billion tower that will rise like a layer cake: two floors of shops near ground level, then a five-star hotel, then offices, then luxury condos on top. The condos, 400 to nearly 600 feet above street level, could become the most exclusive addresses in Boston, with multimillion-dollar views of downtown and the ocean. “The parking will go underground right over there, and you don’t see the parking,” Chiofaro says. “What you see is a great, iconic piece of architecture. How cool is that?”

For years it looked like Chiofaro would never get to build his castle in the sky. In an epic battle of Boston power politics, his ambitions were blocked by a man even more steely than he is: the late Mayor Tom Menino. Their feud was legendary, a media war of press conferences, cutting quotes, and even a Godfather parody video. Today, though, Chiofaro is facing a new Boston. Former construction laborer Marty Walsh is in the mayor’s office, and after years of negotiation, Chiofaro won city and state zoning approval this year to build up to 600 feet—higher than anything else on the waterfront. He is inching his dream project closer than ever to reality.

Still, Chiofaro’s battle is far from over. In July, residents near the garage and the Conservation Law Foundation filed lawsuits to chop down the building’s size, arguing that it’s too big for the ocean’s edge. Though steeped in the legal arcana of Massachusetts’ waterfront laws, the lawsuits pose an almost poetic challenge to Chiofaro the man: The key regulation says new buildings on the waterfront have to be “relatively modest” in size.

Can Don Chiofaro even do “relatively modest”? The very idea clashes with his self-image, his ethos, his drive—the fuel of his past achievements. In what is perhaps a cruel twist of fate, though, it could be the key to whether, late in his career, he can once again leave a lasting signature and transform Boston’s skyline.

Photo by David Yellen

A social relations major at Harvard and captain of the Crimson football team, Chiofaro had a love for both philosophical jousts and bone-crushing collisions. Five-foot-nine and a bruising 225 pounds, with thick hair and eyebrows, he played linebacker, calling the defensive plays and knocking running backs to the turf. “I get very intense about the game,” he told a Sports Illustrated writer in October 1967. “But I’m an intense person, and I get intense about other things, too.” Chiofaro said he found his psychology class just as invigorating—especially when some bookish types dismissed football as a silly pastime. “I know you’re entitled to your opinion,” Chiofaro said he told them. “And I respect you for it. But, frankly, I’d like to come over there and break you in half.”

From the start, Chiofaro was always “an enormous personality,” Berg says. He grew up in Belmont, the son of a beat cop, and enjoyed repartee, “sitting around the room and getting under people’s skin.” Even then, he was driven to achieve, Berg says, and befriended intellectuals, athletes, and professors alike. His lifelong Harvard friends include actor and former football teammate Tommy Lee Jones. “Don was a combination of a very mature person with someone who enjoyed the battle,” Berg says.

After earning a Harvard Business School MBA in 1972, Chiofaro went to work for the star real estate firm Cabot, Cabot & Forbes. He spent the ’70s developing buildings across the country: warehouses, research parks, a Paul Masson wine-aging facility in California. But he wanted to build something bigger. He wanted to make his mark.

Don Chiofaro altered the city’s skyline by building International Place (1) in the 1980s. Now he’s determined to do it again at the Harbor Garage (2).

In 1980 Chiofaro set out to build a skyscraper as big as his ambitions. While working on a development in Westborough, he teamed up with Pittsburgh billionaire Henry Hillman to build an office complex in a forsaken part of downtown Boston next to the Central Artery. The site was a puzzle: 14 lots, a garage, and little buildings, with different owners, on two city blocks. “I see a really complicated problem,” Chiofaro said, “and see an opportunity.” Armed with a box of cigars, he persuaded one parking lot owner to sell. The others followed.

Meanwhile, Chiofaro got legendary architect Philip Johnson to design the complex, impressing Johnson with the quality of the site, which had streets on all three sides and potential skyscraper views of Boston Harbor. Johnson designed two rounded office towers, one slightly taller than the other, looking out over the elevated freeway to the ocean. Chiofaro commissioned a model of Johnson’s design “that cost more than my house in Belmont,” then brought it to City Hall and showed it to Kevin White, who had been mayor since 1968. “Kevin White thought it was outrageously cool,” Chiofaro recalls, “and he said, ‘They’ll probably run us out of town,’ because it was so different than anything else.”

Playing off White’s fondness for calling Boston a world-class city, Chiofaro dubbed his creation International Place. With White’s backing, Chiofaro announced his plan to build the 2-million-square-foot complex in fall of 1983. He was 37. “He was an unknown,” Berg says.

Photo by David Yellen

Chiofaro set out to make an impression. At a meeting with Boston Redevelopment Authority officials, the one he walked into playing “Eye of the Tiger” from Rocky III, he took off his trench coat to reveal his old Harvard football jersey and boasted it was stained with the blood of Calvin Hill, a former Yale running back who’d famously played in the NFL. “He did some very colorful things that may have given people the impression that he was kind of a loose cannon,” Berg says, “but there was always a purpose to that: to become better known and to establish a personality.”

Chiofaro’s negotiating style was confrontational—but when he hit an immovable object, he proved willing to bend. He spent months grappling with the BRA under White’s successor, Ray Flynn. Then-BRA director Stephen Coyle wanted Chiofaro to scale down the towers and redesign the second tower, so that it wouldn’t be a shorter replica of the first. Coyle got his concessions, but it wasn’t easy. “If it were a movie, Robert De Niro would play Don,” Coyle says. “He’s a fighter. He’s a tough son of a bitch. The conversations would exceed a normal office-decibel count.”

International Place, which opened in 1987, is epic and ostentatious, with arched Palladian windows on its façades and soaring ceilings and red marble in the front lobby. Some think it’s over the top. Even Johnson, who designed it, confessed to misgivings at a 1982 conference, calling International Place “2 million goddamn square feet that should not be in this part of Boston.” But its showy grandeur reflects Chiofaro’s style. The developer still spends nearly every morning near the perfectly round water wall cascading from ceiling to floor in the indoor courtyard, drinking coffee outside Au Bon Pain and talking with some of the 6,800 people who work in the complex. “My father was a cop, and he had a beat, and he knew everybody on the beat,” Chiofaro says. “That’s where I get my interest. I’m interested in who’s in the building, who’s coming through the building.”

If the 1980s were Chiofaro’s decade, the 1990s and 2000s decidedly were not. International Place’s second tower opened during the early ’90s, and Chiofaro had to fight his lender in court to keep it from reneging on a loan. His attempts to build in Boston again failed: In 1999 he was booted off an office-tower project near South Station after his partners and city officials decided he hadn’t made enough progress. Less than a year later, Chiofaro lost the right to develop a Seaport parcel when his prospective tenant bailed—and signed instead with the developers of the project near South Station that Chiofaro had been removed from.

Chiofaro’s bad luck continued. In 2004 he even came to the brink of losing his beloved International Place when a New York City firm bought the loan on the building and attempted a “hostile” takeover. Chiofaro declared the firm “a gang of pirates” and vowed to “send the interlopers back to Gotham.” And he did—by filing for bankruptcy protection and getting a new financier, Prudential Real Estate Investors, to take a 90 percent stake in the complex.

Chiofaro emerged from his near-career-death experience more determined than ever to surpass his greatest accomplishment. When he bought the Harbor Garage in 2007 for $153 million, backed by Prudential, he meant to build a sequel to International Place: a signature project next to the Greenway, in a once-isolated location liberated by the Big Dig and the removal of the elevated freeway. But then he hit another wall: Mayor Tom Menino, who didn’t like Chiofaro and didn’t want tall buildings between the Greenway and the waterfront. “The chances of Don Chiofaro building,” Menino said in 2009, are “about as likely as an 80-degree day in January.”

Some attribute the feud to Chiofaro’s and Menino’s general cussedness, or Chiofaro’s refusal to kiss the mayor’s ring. Chiofaro claims he has “no idea” why Menino had a beef with him, but allows that he got on Menino’s bad side. “At some point he had a reason,” Chiofaro says. “Then he forgot the reason, but never forgot that he had it.”

Furious and bullheaded, Chiofaro turned the fight into a public sideshow. He hung a giant red X on the garage’s side, with a white sign that read, “Open to the Sea”—to remind Bostonians of the space he’d open up if he got permission to develop. When critics said Chiofaro had a tin ear, he Photoshopped an image of himself as the Tin Man from The Wizard of Oz. Menino answered with plans to limit new buildings on the waterfront to 200 feet. “I don’t want to Manhattanize the Greenway,” the mayor said. Chiofaro fired back again, holding a press conference at International Place to blast Menino. “We intend to keep the pressure up until we get honest answers from the person pulling the strings on this process, and we all know who that is,” Chiofaro declared.

This got Chiofaro exactly nowhere. “Most people were very deferential to the mayor,” says Vivien Li, who was president of the Boston Harbor Association at the time. “Don was used to being the center of attention.” Menino’s disdain for Chiofaro went as far as mocking the developer in a video parody of The Godfather shown at a gala. A white-haired, white-mustached actor played a supplicant Chiofaro, while Menino, doing a Vito Corleone bit, stroked a stuffed toy kitten. “I believe in Boston,” the fake Chiofaro declared. “I’ve made my fortune here, raising buildings the Italian way, one Palladian tower at a time.” In response, Menino snarled with relish, “If you’d come to me in friendship, your new tower would be up this very day!”

In 2013 it looked like Chiofaro would never build in Boston again. Then Marty Walsh was elected mayor, and everything changed.

At the annual fundraiser for the nonprofit Boston Harbor Now on Spectacle Island, Chiofaro strolls past the celebrity-chef hors d’oeuvres tables. Around him flows the professional class of Boston’s waterfront world: fellow developers, lawyers, consultants. He says hello to two young guys, both state regulators—he can’t remember from which agency. “This is the intersection of everybody that’s involved in my deal,” says Chiofaro, scanning the crowd. He means the Harbor Garage project: its friends and its foes.

The fact that Chiofaro is closer than ever to making his waterfront tower a reality has everything to do with Mayor Marty Walsh. Walsh was a laborer at International Place when it was built, a fact he pointed out on his first visit as mayor to Chiofaro’s 46th-floor office. “I said, ‘Last time I was in your office, it had no walls!’” Walsh tells me. “He’s a big character. He’s down to earth. He could be at the coffee shop on the corner living in the neighborhood as well.”

It’s hardly a secret that the mayor, with his union roots, wants development and construction jobs. Since Walsh took office, his administration has tossed aside Menino’s 200-foot height guideline for the waterfront and Greenway. This, more than anything, has opened up a chance for Chiofaro to build his skyscraper on the Harbor Garage site.

Walsh has been a friendlier face in City Hall than Menino, but Chiofaro still has plenty of foes, and his great comeback is far from a done deal. From the moment he proposed the skyscraper, he and his project have been under attack.

The fiercest opponents, ironically, live in the neighboring high-rises: Harbor Towers, twin 400-foot condo buildings built in the early 1970s. The towers’ residents want Chiofaro to scale back his project’s size, guarantee them parking in his new underground garage, and limit his use of East India Row, a public street between the properties. “Don Chiofaro is very engaging personally—he’s a lot of fun and has a good sense of humor,” says Lee Kozol, chair of the Harbor Towers garage committee, who’s met with Chiofaro dozens of times. But, Kozol adds, “It’s very difficult to get Don to make any substantial compromises in his positions.”

In July, Harbor Towers residents sued Chiofaro over parking and also sued the state to overturn the site’s recently approved 600-foot zoning. As legal leverage, the residents are relying on default state waterfront guidelines that would limit Chiofaro’s building to 55 to 155 feet. “We’re willing to give somewhat on that,” says Marcelle Willock, chair of the Harbor Towers board of trustees, “but the height is a major issue for some people.”

If that lawsuit doesn’t spoil Chiofaro’s plans, one filed by the Conservation Law Foundation (CLF) against the state easily could. The longtime environmental group is a formidable foe that has played a major role in Boston Harbor’s cleanup and has secured transit improvements, including the Green Line Extension, to offset environmental harms wrought by the Big Dig. The CLF also aims to block the new 600-foot zoning height.

The case could turn on a single phrase in state waterfront regulations: a building may exceed existing height limits if it is “relatively modest in size” and won’t impede access to the water or interfere with amenities and activities such as boat docks or fishing. Chiofaro could argue that his building and his open space plans will bolster activities and access to the waterfront. But “relatively modest” compared to what? In approving the new zoning, the state compared his Harbor Garage proposal to “other buildings of the Boston skyline,” including Chiofaro’s own International Place, 600 feet high and two blocks away. Opponents think the project should be compared only to its waterfront neighbors, including the 400-foot Harbor Towers. The lawsuits, however, won’t stop Chiofaro from submitting designs for his tower to the city—which he planned to do late this summer—though they may stop the city from approving construction until it knows whether the new zoning will stand. Now that “there’s a lawsuit,” Walsh admits, “it’ll take a while to move forward.”

Chiofaro, in other words, is in a tough spot. “He needs more height and density than the applicable regulations would allow,” says Fred Salvucci, a lecturer in MIT’s Department of Urban Studies and Planning. “Those regulations were not made up last week. CLF lawyers know those rights, and probably have a strong case.” But a win could block development at the Harbor Garage site—and CLF president Bradley Campbell says his organization, too, wants to see the garage torn down and replaced. “There’s pressure on them and Chiofaro to work it out,” Salvucci says. “If they can’t, it’s likely to just continue to be an ugly parking garage in the wrong place.”

During the party on Spectacle Island, everyone seems happy to see Chiofaro—except possibly Eric Krauss, chief operating officer of the New England Aquarium, who looks stiff and uncomfortable as Chiofaro chats him up. The aquarium once fought Chiofaro’s project, concerned that tearing up the Harbor Garage would disrupt parking and traffic, scare away some of the institution’s 1.3 million annual visitors, and ruin its business. Aquarium officials have shifted to carefully noncommittal now that Chiofaro has agreed to spend $10 million on the aquarium’s Blueway project, which would create a public promenade from the Greenway to the harbor. Still, hard feelings remain, and aquarium leaders are wary. “We continue to have conversations with Don,” Krauss tells me as Chiofaro leaves to get him a beer.

Later that evening, as Chiofaro gets on the boat to the mainland, he greets R.J. Lyman, a lawyer for the aquarium on the Harbor Garage issue. “We don’t always agree on everything, but he’s a really good guy,” Lyman tells me. “Don is dogged and determined.”

To pull off his soaring comeback project, Chiofaro knows he needs more than sheer willpower—he needs friends. Walsh has not only cleared an early path for Chiofaro’s plans, he’s also shown the developer the blueprints to conquering his obstacles by encouraging him to choose diplomacy over battle. “I’ve had some pretty intense conversations with him about this project,” Walsh tells me, about having “inclusive, open dialogue” with the garage’s neighbors. In other words, the mayor has nudged Chiofaro to change his formula for success. Chiofaro’s big personality, a great match for the flashy ’80s, is hardly a perfect fit for 2018 Boston, where the consensus-building convener is king.

As a result, Chiofaro has cut back on the bombast and is learning to play nice, or at least nicer. He’s spent years talking with the city, the state, and the Harbor Garage’s neighbors, mostly aquarium officials and the condo owners in Harbor Towers. “Sometimes it just takes time,” Chiofaro says. “That has become my attitude.” He also attended meeting after meeting about the new zoning rules for the waterfront. Sometimes, Vivien Li says, his answers to questions left people rolling their eyes, and he talked too much about International Place. “He would dominate a room,” she recalls. But Chiofaro soon changed strategy and sent his technical staff to the meetings in his place, letting them answer the endless questions about traffic studies and height, so as not to accidentally annoy.

In the process, Chiofaro has also done what he hates most: make concessions. He’s revised his plans, from two towers to one and from as high as 780 feet to 600. He’s agreed to a thinner tower, down from 1.3 million square feet to 900,000 square feet, with more open space around it. And he’s agreed to spend that $10 million to contribute to the Blueway, the aquarium’s proposed path to the water. In early August, he marked off the proposed Blueway space with a painted blue stripe on the Harbor Garage and a new “Open to Sea” sign.

And yet he seems genuinely enthusiastic about creating a place of beauty in harmony with neighbors and the aquarium. “He’s mellowed a little bit, particularly in some of his dealings,” says Dave Hawkins, a friend and longtime International Place tenant. “Don’s being a little bit more flexible than he once was.” Coyle agrees. “He spends more time patiently working behind the scenes,” he says. “The 1984 Don Chiofaro was always calling blitz. The 2010, 2015, 2020 Don Chiofaro is a sophisticated, savvy developer.”

Drive and persistence are still central to Chiofaro’s self-image, but he allows that he may have adjusted what they mean to him: less pushiness, more garrulous camaraderie. “I actually find the robust conversation with everybody involved really interesting,” he says. “[It’s] interesting to try to think about the world from their point of view.” Chiofaro also says he’s finally willing to play the long game. “I can’t force things to happen,” he says, even though “I’m by nature not particularly patient.”

After all, he says, he’s probably seven years away from opening his new skyscraper. That takes him to 2025—when he’ll be 79. “I’d like to get it done,” he says. “If it takes a little bit longer to get to the right result, I’m okay with that.” More so, Chiofaro is confident he’ll reach an agreement with all of his opponents. “All those people that aren’t my friends will be my friends,” he says. “We’ll work it out.”