Anarchists, Horses, Heroes: 12 Things You Didn’t Know about the Great Boston Molasses Flood

The weirder and more notable aspects of the disaster, via Dark Tide author Stephen Puleo.

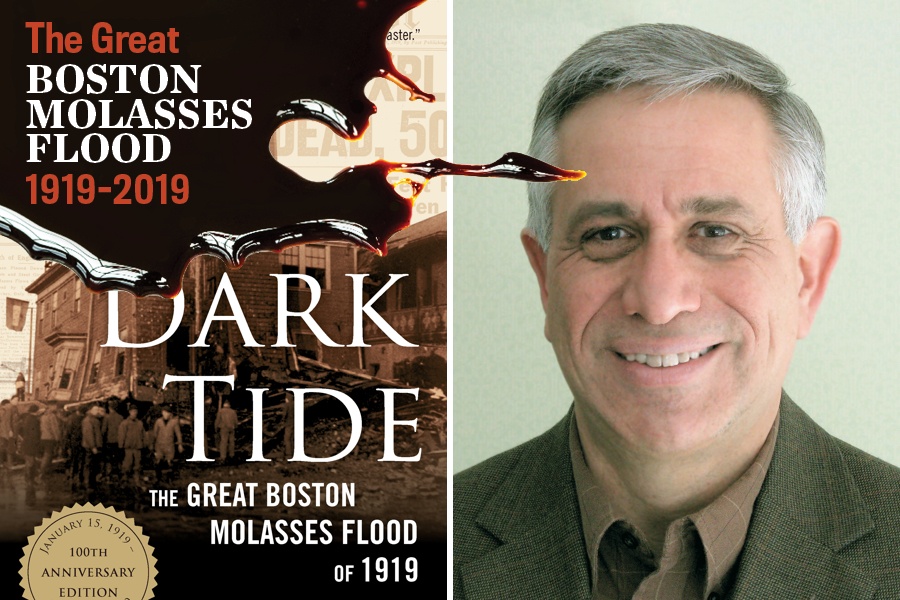

Headshot and book cover courtesy of Beacon Press

The 100th anniversary of the Great Boston Molasses flood is upon us, but many still fail to grasp the significance of the event, if they’ve heard of it at all. Stephen Puleo, author of the definitive book on the subject, Dark Tide, has spent the last decade-and-a-half telling the story how a massive wave of dark syrup changed the course of history, redefined a neighborhood, and was more gruesome than you probably realized. We asked him to walk us through some of the most notable bits from the tragedy that you should absolutely know.

The molasses company tried to blame the incident on terrorists

We now know in great detail how a shoddily built tank caused the disaster, as more than 2 million gallons of goo burst through its rickety steel shell and wreaked havoc on the streets of the North End. But the company that owned the tank, U.S. Industrial Alcohol Co. claimed in court that the flood was actually the work of an anarchist terrorist cell.

“The theory was an anarchist climbed a ladder and dropped a pipe bomb into a fermentation vent, and that’s what caused the tank to explode, so therefore [USIAC] should be absolved of responsibility because it was a terrorist act,” Puleo says.

It wasn’t impossible, as bombings were common at the time, and police investigated the theory. But there was a big problem for USIAC: “There was no evidence,” he says. “It’s very clear that the tank was built in a very substandard way.”

So the judge ruled against the company, and ordered it to pay millions in damages.

Boston Herald news clip via Boston Public Library

The molasses was full of deadly junk

“It picks up everything in its path—carts, animals, wood, houses, debris from an overhead train trestle,” he says. “That’s how a lot of these injuries happened—fractured skulls, broken pelvises, broken backs. People are kind of hit by this debris as it’s being swept by the wave. It’s just a very harrowing kind of disaster.”

Some of the dead were found in Boston Harbor

“They were knocked into the water by the wave [of molasses]. In fact the last person is found I believe three or four months after, under a pier.”

It was a bad day for horses

“There are horses in a stable nearby, and half of them were killed instantly upon impact but the other half, 10 or 11 horses, are killed that night—shot by Boston Police—because they are so enmeshed in molasses they can never be extricated. It’s kind of quiet on the waterfront at night except for the reverberation of gunshots around the harbor as these horses are being put out of their misery. Kind of an eerie scene.”

It led to an incredible phone call

“Send all available rescue vehicles and personnel immediately! There’s a wave of molasses coming down Commercial Street!” That was the once-in-a-lifetime message the Boston Police received from Patrolman Frank McManus, who witnessed the tank erupting.

“I don’t think that call will happen again,” Puleo says.

Quick thinking saved lives

Take, for example, the train conductor Royal Albert Leeman: “There’s the elevated passenger line that ran right above commercial street, and when a big piece of the tank severs the main support, a train had just gone by and jumped the tracks. The conductor is able to get out from his vestibule, makes his way across the tangled wreckage and stops another train from plunging to the street below. Those passenger trains ran every seven minutes between South Station and North Station,” Puleo says. “He was kind of a small hero.”

The Boston Elevated Railway, 1901 photo via Boston City Archives

It really did smell like molasses in the North End—for decades

Although it’s been exaggerated a bit in folklore, it’s not an urban legend. The sweet smell of molasses lingered in parts of the North End for years after the tragedy.

“I had a gentleman raise his hand at one of my presentations who said he was a meter reader for Boston Gas in the late 1950s and early 1960s,” Puleo says. “When he went into the basements of those buildings across the street [from the site of the tank], he could still smell molasses. Which makes perfect sense to me, because those basements were filled up to the first floor with molasses.”

Plenty of people knew something was up before tragedy struck

During the four years it was in operation, workers reported hearing groaning noises every time the tank was filled with syrup, and it was well known that the structure was leaky, particularly to neighborhood kids. “Kids would collect and eat the molasses that oozed out of the tanks,” he says.

It could have been a lot worse

“When this wave disgorges, it comes out at about 35 miles an hour. So the term ‘You’re as slow as cold molasses in January’ does come from this flood, but it is not slow. It comes out really fast, and recoils off Copp’s Hill. If the topography of Copp’s Hill went the other way, instead of sloping down to the harbor, you may have had hundreds or even thousands of deaths, had this thing gone the other way and gone into the heart of the North End.”

Photo of Copp’s Hill, undated, via Boston City Archives

It was rare to see a company held responsible

In an extremely business-friendly legal environment, it was common at the time for companies to avoid responsibility for negligence—like, for example, building a giant rickety tank in the middle of the North End and filling it to the brim with deadly syrup until it burst. “It’s not like it would have been this great outrage” if USIAC had gotten away with it, he says. “It was expected! When [the judge] rules against the company, it’s a big deal.”

Victims who suffered before they suffocated were paid more

How do you decide how much it’s worth to your family if you drown in molasses? That was up to Judge Hugh Ogden, who oversaw the years-long civil suit that came after the disaster, and took responsibility for distributing damages at its end. If your death was especially horrific, your family got more money (That’s true, by the way, in modern-day wrongful death cases, too).

“[Ogden] basically awarded $6,000 [or, roughly $600,000 today] to people who were killed immediately, like 10-year-old Maria Distasio, who was killed instantly,” Puleo says. “Then he gave $7,500 to people who suffered before they died, like George Layhe. He was trapped in the basement of a firehouse in this little 18-inch crawlspace and tried to keep his head above molasses for about four hours before he was finally asphyxiated.”

The disaster changed safety rules around the country

“Virtually all of the building construction standards that we take for granted today—that architects need to show their work, that engineers need to sign and seal their plans, that building inspectors need to come out and look at projects—all of these are a direct result of the Great Boston Molasses Flood. First in Massachusetts, and then it kind of ripples across the country. There’s no question about that,” he says. “The Great Boston Molasses flood did for building construction standards what the Cocoanut Grove Fire did for fire standards.”

Learn more about the Great Boston Molasses Flood, 100 years later.