How a Verizon Cell Tower Began a Furious Debate in Wayland

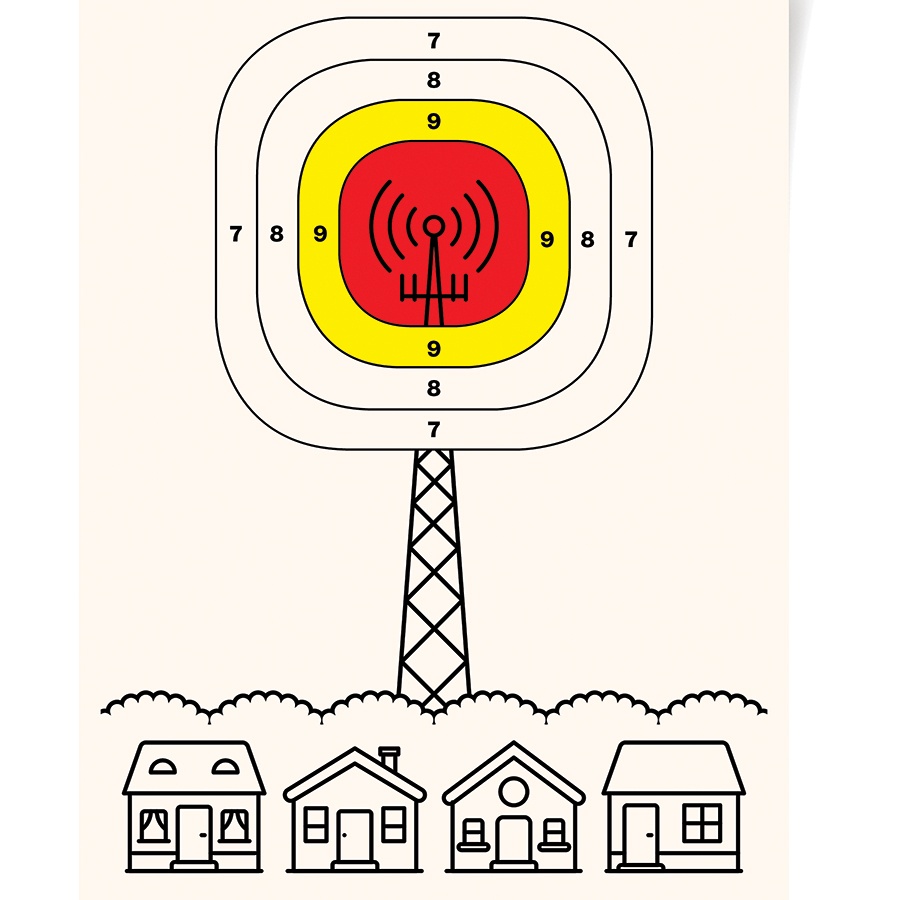

A shooting range, a 141-foot cell tower, and a mob of angry neighbors in one of Boston’s toniest suburbs. Inside the feud that’s bringing Wayland to its knees.

Photo by Benjamen Purvis/iStock

On a cloudless morning last December, I found myself walking around the Oak Hill Road neighborhood in my hometown of Wayland with resident Tom Gulley, who was snapping photos of an orange balloon swaying gently in the wind, head and shoulders above the tree line. Despite the calming warmth of the sun, Gulley was fuming. I’d never seen anyone so worried or angry about a balloon, but this one was marking the spot where a proposed cell-phone tower would rise out of the woods near Gulley’s home.

When Verizon Wireless started negotiations to build a 141-foot tower there several months earlier, they had every reason to think it would be a home run. After all, the proposed location—a nondescript, 2,000-square-foot plot of land on a heavily wooded, 15-acre property, bordered by miles of undeveloped wetlands and the Sudbury River—seemed the ideal spot to close a service gap in southwest Wayland. What could possibly be wrong with that?

Well, far more than Verizon could imagine.

Gulley and his neighbors were outraged at the prospect of a towering eyesore and its potential health side effects. Bright-yellow signs proclaiming, “No towers near our homes” began sprouting from the lawns in Oak Hill and angry letters started appearing in the local paper. From a distance, it looked like a classic case of suburban NIMBYism. But this feud isn’t just about the cell-phone tower. It is the latest battle in a deeply rooted conflict that’s been tearing apart the Oak Hill area for decades.

The neighborhood takes its name from a gently winding road lined with neat clapboard Colonials and raised ranches on well-manicured lots. It’s only 20 miles from Boston but feels far removed. Herons fly overhead, and crickets provide the soundtrack on warm summer evenings. It’s the kind of place you could picture raising a family—until the crack of gunfire shatters the calm, sending dogs into a barking frenzy and geese scattering with protesting honks. Children pause their backyard play, while anxious parents hurry over to windows to peer outside.

These regular blasts come from within the confines of the Wayland Rod & Gun Club, a 120-member sporting facility that owns the land where Verizon is planning to build the cell-phone tower. For years the neighbors have been warring over noise levels with the gun club, which lies in the heart of this residential neighborhood, and have been determined to shut it down. Now the proposed tower has upped the voltage on the conflict and put residents over the edge.

Last November, for instance, an angry neighbor named John Grabill wrote a letter to the Wayland Town Crier referring to gun-club members as a “mean-spirited, uncompromising, out-of-touch group of people who feel they have a right to ignore hundreds of family members surrounding their firing range just so they can blast away at will.” Another resident tells me that the club is a “good old boy network” and “not a good neighbor,” nor a “good citizen of Wayland.” Later, Grabill tells me the sound from rifles is so jarring that babies can’t nap and children are “scared to death.” He adds, “When we ask the gun club to build some berms or baffles to deflect the noise, they smirk and say no. Their attitude is, ‘We can do whatever we want’—whether it’s about the noise or the cell tower. They’re not willing to compromise on anything.”

Gun-club members are fed up, too. Club president Stephen Garanin says that for years they’ve tried to be good neighbors by inviting residents to visit the property, hosting community programs, and supporting charitable causes. He says members are tired of being taken to task by a vocal, “micro-minority” group for enjoying a sport that’s harmless and legal. Not to mention, he says, the neighbors “knew what they were getting” when they purchased homes there. “We have no hidden agenda. They shouldn’t be surprised.”

This month, the town zoning board is expected to decide whether Verizon’s tower deal with the club will stand. In light of recent competition from a new, much fancier gun club in Weston, an unexpected tax assessment, and legal bills from all the wrangling with neighbors, the cell-phone tower could be the lucrative lifeline the club’s been looking for—but not if the neighbors have anything to say about it.

The Wayland Rod & Gun Club was founded in 1928, decades before most of the 60 or so surrounding homes were built, as Garanin is quick to point out. Created by a handful of men who wanted a place to hunt and fish, the 15-acre club comprises a 45-foot indoor range in the basement of a stately brick Colonial and a 100-yard outdoor range built into the hillside, where members can shoot pistols, rifles, and shotguns. At first, the club had very few neighbors and even fewer problems. For 50 or so years, it remained mostly off the radar, and there’s nothing in town records that indicates objections to club activities, which included target shooting and, for the first several decades, trap shooting of clay pigeons.

Over the years, the Oak Hill neighborhood grew as young families realized it was an affordable entry point into this affluent town. Sure, there was a gun club down the street—but that was a compromise home-buyers were willing to make to live in Wayland, with its proximity to Boston and highly rated public schools.

Once the area became more densely settled, however, the complaints started. Some neighbors took issue with the way the sound of trap shooting reverberated across the wetlands. “You’d hear it once, and then the sound would come echoing back,” one longtime resident, who asked to remain anonymous, told me. “It was impossible to sit outside and have a conversation.”

In 1990, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service investigators received a tip about the club’s trap shooting and soon grew concerned about the effects of the lead fallout on groundwater and wildlife, particularly the ducks in the adjacent Great Meadows National Wildlife Refuge. At long last, the neighbors—who were likely the whistleblowers—got some respite when the agency issued a verbal cease-and-desist order to the club intended to last until the extent and impact of any lead contamination could be determined.

The club retained lawyers and hired consultants to devise a proposal for environmental services. However, as far as I can determine from both building- and health-department records, it was not required to do any major cleanup of the land and was ultimately allowed to reopen—but without trap shooting of clay pigeons.

Still, that didn’t stop complaints from neighbors, who insisted that the club had started using higher-caliber and louder weapons than it did when they bought their homes. It’s a charge the club denies, saying that, if anything, the caliber of weapons has dropped over the years. But the neighbors weren’t having it. In 2013, two dozen of them filed a petition with the Wayland Board of Health to stop “excessive noise,” which they said was exceeding the ambient noise level by greater than 10 decibels, in violation of state Department of Environmental Protection regulations on noise pollution. In a Wayland Town Crier article, John McConnell, a spokesperson for the petitioners, said that ambient noise levels in the neighborhood measured 40 to 50 decibels, “but I have recordings of up to 120 decibels when firing was taking place at the club.” (Noise above 120 decibels can cause immediate harm to hearing, according to the Centers for Disease Control.)

In response, the Board of Health informed the petitioners that gun clubs are exempt from the DEP’s noise regulations, and then promptly passed the complaint to the Wayland Police Department to handle. McConnell met with club board members to find ways to mitigate the noise, including soundproofing equipment, but again, nothing came of it. (McConnell eventually washed his hands of the problem, retiring to Florida with his wife.)

Then, in October 2015, the town received an anonymous tip: The club’s caretaker, Paul Ramsey, and his wife had been living in private quarters on the second floor of the gun club for decades, even sending their children to Wayland Public Schools, yet the club hadn’t been paying property taxes on the residence. Instead, the club’s three parcels of land had been exempt as “real estate owned and occupied by a charitable organization.” A review by the town lawyer, however, determined that the club was not exempt and should be assessed. The club soon filed to reclassify most of its 15 acres as recreational land, reducing its taxes by 75 percent. Still, the $7,194.31 bill was a significant hit for a modest, no-frills club not accustomed to paying any property taxes. But luck was in its favor. A few months later, Verizon came calling.

When Verizon proposed building the 141-foot monopole on a small parcel of the club’s land, the gun-club board ushered them in. The deal seemed irresistible: The club would lease roughly 2,000 square feet of land to Verizon and receive payments in exchange for the wireless carrier operating the tower. Neither the club nor Verizon would tell me the price of the lease, but from a look at rates online, the club could stand to make tens of thousands of dollars a year. The only catch—besides the possibility of further infuriating their already fed-up neighbors—was the fact that the club falls outside both of the two designated “wireless communication districts” in Wayland, which means it would need a variance from the town’s Zoning Board of Appeals. Verizon applied for the variance in December 2017 and is awaiting the ZBA’s decision this month.

Meanwhile, Tom Gulley says, a group of residents have hired a lawyer, believing the “in-your-face ugliness” of “the largest tower for miles” will adversely affect the aesthetics of their neighborhood and hurt property values. The average tree height in the area is about 80 feet, he tells me, so this tower—at 141 feet—will be quite visible. The group also expressed concern about the dangers from magnetic waves being emitted by the tower.

Moreover, the neighbors say they haven’t had issues with cell service. For Verizon to get a variance from the town, the company needs to establish a significant gap in coverage. At a November ZBA meeting, the neighbors’ lawyer, Samuel Perkins, argued that “there is not a single documented instance in anything Verizon has submitted to you of anyone suffering from poor performance.” Verizon must also show that there’s no feasible alternative to the spot they’ve picked. Its application included a detailed alternative-site analysis documenting more than 160 possible locations it had considered and evaluated. All were deemed nonviable, for reasons ranging from residential use to wetlands/conservation land to visual impact. Several potential sites never responded to Verizon’s inquiries, and Perkins, the neighbors’ lawyer, said that some of Verizon’s investigations “do not involve a whole lot of diligence.” Rather, he claimed, they “involve sending out one certified mail letter and getting no response. And then doing nothing else.”

Conversely, Verizon’s lawyer, Christopher Swiniarski, tells me that Wayland residents have indeed testified at public zoning-board meetings expressing dissatisfaction with wireless service in the town, and that at least one has sent a letter to the ZBA stating as much. The company also maintains that the gun club is the most viable option because it’s “the only property of sufficient height that is not either wetlands or a residential property.”

Gun-club members are very matter-of-fact about the situation. “Verizon came to us,” Garanin explains with a shrug. “Verizon says there’s a need.” Garanin, who lives just over the town line in Sudbury, points to himself as a prime example of someone who will benefit from the tower, saying he has poor cell coverage and knows people in his neighborhood who have to stand outside to use their phones. “We’re not trying to hurt anybody,” he says of the proposed tower. “But only 20 out of 5,000 Wayland homes are [negatively] affected by the tower. It’s a sad day for any town when a micro-minority…of its citizens feel they should halt something that is a significant safety issue: cell phone service. The fact that hundreds of Wayland residents have no, poor, or intermittent service does not seem to concern the self-appointed anti-tower watchers.”

In Oak Hill, however, the tower seems to represent more than a potential eyesore, health hazard, or unnecessary service improvement. As one opponent told me, the deal with Verizon is the club’s “140-foot middle finger” pointed right at the neighborhood.

As one cell-tower opponent told me, the gun club’s deal with Verizon is a “140-foot middle finger” pointed at the neighborhood.

The irony is that if someone hadn’t alerted the town to the family living in private quarters on the second floor, the club wouldn’t have been assessed a property tax and thus might have been less inclined to negotiate a deal with Verizon. One thing is certain, however: If the deal goes through, the neighbors will not only live next door to a gun club, but to a cell-phone tower, too.

Both sides of the dispute are anxiously awaiting the Zoning Board of Appeals’ decision this month as to whether it will grant the gun club a variance and clear a path for the cell tower. Even if it grants the variance, though, there’s one more catch: State law gives town selectmen the right of first refusal to buy the 2,000 square feet of land if the Verizon deal goes through. That’s because that sliver of land will be converted to commercial property, and the change of use gives the town the right to purchase it at full market value, or transfer it to a conservation nonprofit.

Will the selectmen exercise that right? The neighbors hope so, while Garanin scoffs at the idea. Why would the town want to do that? he asks me incredulously as he leads me on a tour of the club on a crisp December afternoon. He points out the unassuming plot of land—strewn with fallen leaves, discarded wood pallets, and other detritus—that’s at the center of the controversy. I see what he means: There’s not a lot the town could do with 2,000 square feet in the midst of a working gun club.

From the base of the proposed tower, I can see just one house, and the rear windows of another home in the distance—and I understand why the gun club thinks it’s a good spot to build a cell tower. But as I peer through the woods, I can also make out the outline of the baseball field where my 12-year-old twin boys play ball every spring. I remember sitting on the bleachers with other parents during games and hearing the blast of guns firing repeatedly 100 yards away—and watching in horror as my boys and their teammates staggered and fell to the ground one by one, as if they’d been shot. That’s a hard image to shake, especially in this era of mass shootings—and a reminder that there’s more to this story than simply a cell tower in the woods.