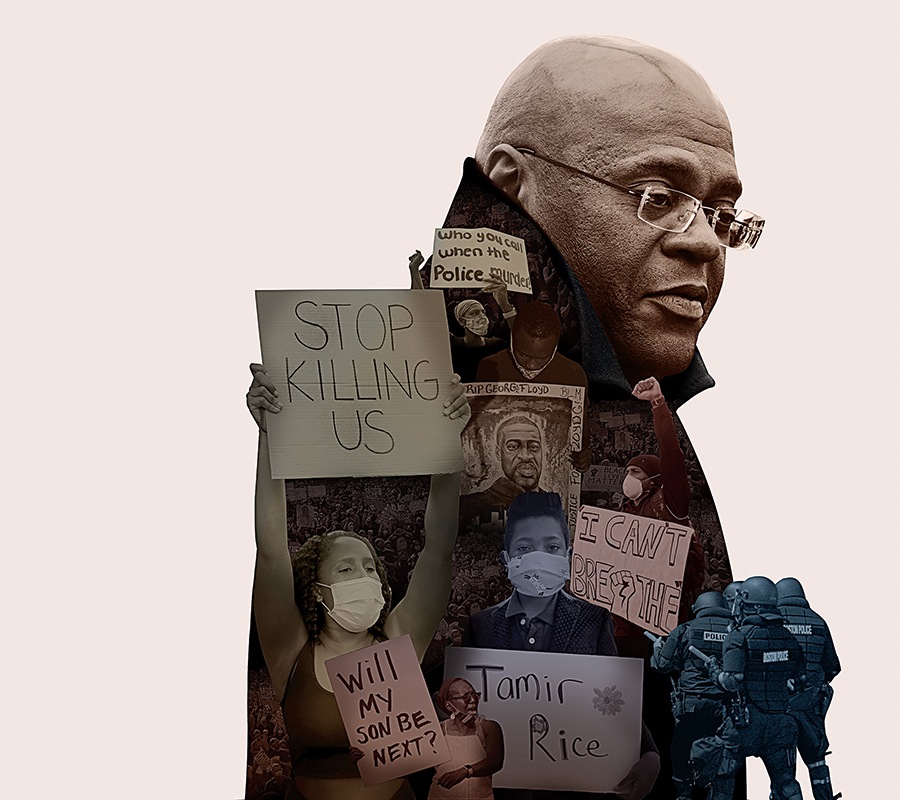

Who’s Gonna Take the Weight: Mo Cowan and Being Black in America

As a Black man born in the South who has climbed the power structures of Boston and our nation’s capital, I’ve spent a lifetime navigating around and tackling head-on the realities of structural racism. It’s time for everyone else to know this burden.

Illustration by Benjamen Purvis

You may think you know something about me, but I want you to really know who I am. I am an executive at a Fortune 500 company. I am a former U.S. senator and chief of staff to Governor Deval Patrick. I have been a partner at a major law firm, CEO of a consulting group, and served on several corporate boards. I am a husband and a father to two sons. But who I am really is a Black man in America.

Because I am Black in America, and a Black parent in America, I live with a sense of hopefulness tempered by an ever-present fear and dread. Often, this sense of fear and dread is low-level and remains hidden from view by the many masks that I wear in the roles I listed above. You know: the masks that people like me regularly don to “fit in”—which, of course, really means to make others comfortable with my Blackness. But that low-level fear is reaching a crescendo as I see more and more images of my community enduring discrimination and other indignities, and even meeting death at the hands of American systems built on the notion that Black lives don’t matter as much as others.

Now, neither my kids nor I have suffered at the hands of the police, nor recently encountered the likes of an Amy Cooper, who would sooner choose to endanger a Black man’s life than keep her dog on a leash. Yet we see ourselves in the contorted face of George Floyd as he begged for his life while a sworn police officer slowly—and nonchalantly—executed him on a public street. I break into a cold sweat as I think about Breonna Taylor lying in bed as men, armed with guns and badges, burst into her home and opened fire, stealing her life. My oldest son is about the same age Trayvon Martin was when he was killed walking home from the store. And my younger son is almost the same age Tamir Rice was when he was shot and killed by a police officer in a public park. My sons know these names because they have all been added to our “Talk” about being Black in America.

The Talk is the ongoing conversation we have with our kids about navigating and surviving a world still hostile to Blackness. The Talk is about passing on to your driving-aged child all of the unwritten rules for a traffic stop: hands at 10 and 2, open the window to eye/ear level, make no sudden moves, call your parents and leave the line open, do not reach for the dash or under the seat (even if that’s where you keep your registration) without permission. In short, do everything—or nothing, as the case may be—to make sure you come home safely. The Talk offers guidance about what to do when you are challenged because you “don’t look like you belong” where you are. The Talk is triggered by images on the news or incidents in the classroom. The Talk happens in the barbershop and around the dinner table. The Talk starts much earlier than it ever should and never seems to end.

In the wake of Mr. Floyd’s death at the hands of the police, as protests and calls on the streets lead to Talks in the boardroom, I am using my seat at the table to share my own Black experiences. More White colleagues and allies than usual have been interested in hearing these as of late. I tell them what it is like to walk past a car and hear the occupants lock their doors. Or to be asked to retrieve someone’s vehicle from the valet while I’m waiting at the valet to collect my own car. I share how I instinctively freeze in place—in my own backyard—when I see a police car patrol my street, almost as if I can will myself invisible to the officer’s gaze. I describe the amount of time and attention I give to my attire before I go to the bank so as to not seem out of place or threatening. I talk of serving in the U.S. Senate, of wearing my senator’s lapel pin and still being told the tram was for senators only, asked by security—outside my own Senate office—to step aside so another federal official could pass undisturbed. The shocked and surprised responses to hearing about these experiences are all too familiar: “How could that happen to someone like you?” As if my credentials, my tailored suit, or the ZIP code in which I live matters—or should matter—when you are Black in America.

When Amy Cooper called the police on Christian Cooper in Central Park, why was so much attention given to his Ivy League degree and professional background? When Colorado police killed Elijah McClain, would we all have moved on if he were not universally described as a sweet and innocent young man? Why do we rush to list any past transgressions and imperfections of Black victims who die at the hands of police? Would those who hesitate to say, “Black Lives Matter” be less reluctant if they could publicly say what they may privately believe—only some Black lives matter and the rest are expendable? For most Black people, this framing is not only offensive but also divorced from our reality.

The reality is that conformance to mainstream standards of education, socioeconomic standing, or behaviors acceptable to mainstream White America do not protect Black bodies from systemic racism. You just learn to navigate, survive—and occasionally thrive—in these systems and structures. That is what I have done, and what I try to teach my children to do.

Survival: that is what we Talk about in Black families. Navigating and enduring the unnecessarily challenging experience of being Black in this country. A Black friend with kids younger than mine recently asked how I learned to discuss violence against Black people and Amy Cooper–like offenses with my sons. I told him my conversations were still works in progress—but I wish I had fewer occasions to perfect them. But what of the conversations that do not happen enough in the living rooms of other homes across America? I have felt envy as so many of my White friends and colleagues admit to me that they have never felt the need to have a Talk with their children and have never known the anxiety that is so familiar to so many Black people. I jealously wonder: How freeing must it be to never know this burden?

Is this the moment when all of us—finally—are ready to discuss systemic racism and White privilege honestly and openly? Will this moment gain momentum and truly become a movement leading to real and sustainable change? Will this finally be a time of reckoning and reconciliation? If it is to be, people and others must become comfortable being uncomfortable and move beyond what Ibram X. Kendi calls “feelings advocacy”: convincing yourself that you are taking action to solve racism, when all you are really doing is trying to make yourself feel better. Because when we focus only on how “bad” we feel about what is happening, our advocacy ends when we feel better. You donated; you read a book; you’ve “done your part” so you can ease your conscience and move on. Black Americans do not have the privilege of moving past systemic racism. Ever. No one should enjoy this privilege.

This isn’t to say that you should stop donating or that you shouldn’t read everything you can on being anti-racist. Do the work. Donate, protest, educate. Engage in difficult conversations with family members, friends, mentors, and colleagues. But make that merely the start of your work. Commit to trying to understand the discomfort that Black America has felt for centuries. Focus on the injustice, the inequality, the racism that remain too large a part of the American experience for so many. Get comfortable with feeling uncomfortable so that we can look past our feelings toward crafting the necessary solutions.

In order to make change, we need to ask what we are willing to commit to every day to challenge ourselves and one another. This is the true call to action for the “newly woke”: Do you have the stamina to drive systemic change and do the work? Political momentum reached an all-time high early this summer. Will that enthusiasm to engage and drive change still be there when the Celtics and Sox resume their COVID-19-shortened seasons? If the beaches on the Cape and Islands are once again filled with residents and visitors alike, will you still head into the hot summer streets and cry out for justice?

Momentum and stamina are needed because structural and systemic racism will not disappear overnight. The past 400 years have shown this. Nor will the many who have long benefited from the way things are readily give ground, but giving ground is what is necessary if we ever hope to live out the promises of our founding documents. This moment requires you to bring up issues of race, injustice, and inequity at your dinner table and to your elected officials as much as I do. You must recognize structural racism for what it is, because to do otherwise is to deny the reality that is part of the American experience for many. It is part of our history and our present. Will we take action to ensure it is not part of our future?

As we work on our personal growth, we must also not allow the business community—which enjoys incredible influence over policymakers across the political landscape (I should know)—to engage in their own form of feelings advocacy. Social media campaigns, full-page newspaper ads, and financial pledges to combat systemic racism can be helpful, but they will not be enough to drive sustainable change. Internal and external stakeholders are demanding that diverse leaders be added to executive teams and boards of directors. They’re also challenging companies about how and whether their spending with business partners and vendors supports business equity. And the corporate community will need to honestly assess and, where necessary, change hiring and promotion practices to live the language in the ubiquitous diversity, equity, and inclusion statements on everyone’s website.

Keeping up the momentum will not be easy. It will be tiring; it will be uncomfortable and it will be hard. But it is necessary if we have any hope of making the reality of America become more like the promise of America. If you truly love the idea of what our country stands for, you must be willing to criticize America when we fall short. To be Black in America is to know the stamina and fortitude it takes to survive being Black in America. It’s time for the entire country to show this same strength and truly lean into this fight for equality and justice. It’s time for us all to do the work.

Mo Cowan is an executive at the General Electric Company and a former interim U.S. senator from Massachusetts. Parnia Zahedi is a 2020 graduate of Georgetown University Law Center and previously worked with Cowan during their time at Mintz and ML Strategies.