A Slaying in the Suburbs

Katie McLean thought her marriage to a celebrated surgeon would last a lifetime. Then her body was discovered in a pond. Inside the suburban romance turned nightmare that rocked the town of Dover.

Illustration by Comrade

On a warm evening in mid-May, Ingolf Tuerk pulled his silver Mercedes G-Wagen into the three-car garage at 29 Valley Road in Dover and sat down with his wife, Katie McLean, and three stepchildren for dinner. Familiar scenes of placid domesticity played out in similar homes across town, a wealthy pastoral suburb dotted with riding stables and sheltered by hundreds of acres of woodland reservations. This particular meal, though, marked a momentous occasion and a new beginning: Tuerk and McLean had been separated since early February, and Tuerk had not set foot in the house since then.

A lot had changed in three short months. Bubbly and outgoing, McLean had a talent for making new acquaintances almost anywhere she went, volunteered her time at a handful of charities, and was famous for throwing seasonal holiday parties. Since the pandemic struck, though, she’d spent her days quarantining inside and scrubbing down her kitchen’s granite countertops with Lysol. She’d also devoted herself to helping her teenagers, assisting with schoolwork, orchestrating art projects, and going on family nature walks along the nearby hiking trails to lift their spirits. Most important, McLean thought Tuerk had changed, too. Having built a career as a New Age energy worker, McLean believed that people could grow and that love had the power to heal even the deepest wounds.

She also believed in signs from the universe. When a family of house finches built their nest behind the ornamental spring wreath she hung on the front door, McLean decided it was a good omen. And so, on the evening of May 14, 2020, right when the four little nestlings were about to take flight, McLean welcomed her husband back into their home.

The pair were quite the couple: Tuerk, a well-known surgeon at St. Elizabeth’s Medical Center with a muscular build and thick German accent, and McLean, a Reiki master with striking red hair. Together, they had five teenagers in Dover public schools: her three children from a previous marriage and Tuerk’s two children from his second marriage, who lived primarily with their mother but often frequented the house. McLean, an all-American girl from Belmont, flew a German flag in honor of her husband below her Stars and Stripes from the tall pole on their green lawn—arguably the most perfectly manicured on Valley Road. Tuerk saw to it himself; on weekends he could be found in front of his Colonial mansion riding back and forth on his lawnmower, barefoot.

In February, though, McLean was planning to file for divorce and took down the German flag. Over the next two and a half months, Tuerk alternated between a room at a lodger’s hotel in another town and a friend’s RV in Florida, while he made plans with real estate agents to sell the family home. Though they had been engaged since March 2018, when McLean moved in, the couple had only officially been married for a few months, and the house was still in Tuerk’s name alone. In late April, as a gesture to signify his devotion and commitment to their reconciliation, Tuerk added McLean’s name to the deed for the house. It was their place now. McLean could go ahead and take down the for-sale sign marring the lawn and put the German flag back up. He was a new man.

Dinner went well, and after the meal, Tuerk, McLean, and the three children gathered around the plush leather sofas and laughed while playing a board game. Afterward, the kids went to the basement to watch TV while McLean and Tuerk stayed in the living room, talking over drinks. It wasn’t long, though, before they fell into old habits, arguing about text messages and fidelity. McLean hated to expose the children, who could hear the yelling, to their fights, so she and Tuerk went upstairs to the bedroom and shut the door behind them.

Later that night, after the kids had gone upstairs to bed, one child heard a thump. The other heard the dog bark, and the heavy footfalls of Tuerk pacing. When they were living together, Tuerk made McLean coffee in the morning. But when the children awoke the next day, the house was quiet and there was no earthy smell emanating from downstairs. The door to the master bedroom was locked and both cars were gone.

Meanwhile, word of an odd text message circulated among McLean and Tuerk’s social circle, along with a growing ripple of concern. “She is a vindictive devil, she played us all,” Tuerk wrote to two friends at 4:31 that morning, according to a police affidavit. He also added that he was sorry. Tuerk didn’t respond to calls or texts asking him to elaborate on what, exactly, he was sorry about. McLean wasn’t answering her phone either. It was as if both of them had simply vanished.

McLean and Tuerk’s relationship began like any modern romance: online. It was November 2017. Both of them had finalized their second divorces within the past year. Drawn to his rugged good looks, McLean was intrigued by stories of the surgeon’s humble beginnings in communist East Germany. Tuerk admired McLean’s maternal instincts and took her out for meals, live music, and rides on the back of his motorcycle around Dover, where he had recently bought a house.

Tuerk served as chair of the urology department at St. Elizabeth’s Medical Center, where he was celebrated as a kind of Arnold Schwarzenegger in medical scrubs. He not only rode motorcycles, but also claimed to have served as an alternate in the 1980 Olympic decathlon and was an early practitioner of robotic prostate surgery. After completing his residency in Berlin, Tuerk was recruited by American doctors to teach his novel technique in the United States. When Tuerk arrived in Virginia in 2001, he was married to his first wife and had three children. During a stint teaching in Virginia he met his second wife, with whom he returned to Germany for several years before moving back to Massachusetts to work at the Lahey Clinic in Burlington. In 2008, St. Elizabeth’s hired him, and he eventually became a key feature of the hospital’s advertising campaign. Billboards of Tuerk’s hulking image, complete with a Harley-Davidson skull cap, towered over highways. A promotional video featured Tuerk pulling up to the hospital on his motorcycle, flexing his muscles and declaring, “Surgery is physically very demanding work.”

McLean, on the other hand, advertised her services as a Reiki master, psychic, and medium by word of mouth. Krystal Harrington, an eyelash technician in Hudson, often sought McLean’s help to clear energy blocks and connect with her late grandmother. “Katie knew things that nobody would know,” says Harrington, adding that McLean’s psychic readings almost always had a positive bent. Not only would McLean offer advice as though she were a friend, but many of her clients, including Harrington, said she often confided in them as well. She was one of those people “you really and truly wanted to be around,” Harrington says.

When McLean met Tuerk, she was a single mother living in a three-bedroom house in Sudbury. After a whirlwind four-month romance, Tuerk proposed to McLean and invited her and her three children to move into his new place, a four-bedroom, 5,380-square-foot home with gleaming hardwood floors that he had purchased for $1.7 million. It was almost identical to the Dover home he had owned with his second wife.

When McLean opened the wood-paneled door to 29 Valley Road for the first time, she found an empty house. The lack of furniture was no problem; she loved to decorate. Tuerk was a penny pincher, but that was something McLean could take care of once she sold her Sudbury house, which was Tuerk’s idea, according to court documents. Her clients also say that Tuerk told her to go ahead and sell her minivan, too, because he would let her drive his G-Wagen that she so adored. And she could stop paying rent for studio space as well. Why not see clients in the house, if that was something she still wanted to do? All of her needs would be taken care of so long as she paid $1,000 a month toward the mortgage and chipped in to renovate the basement gym and outdoor pool.

At first, their visions of domesticity complemented each other well: McLean, a self-described neat freak, liked the idea of being a modern-day homemaker, and Tuerk liked his home to be orderly. Every day when Tuerk pulled his motorcycle into the driveway from the hospital, he found a spotless home, and his beautiful girlfriend, waiting to pour him a drink and sit with him on the couch while he relaxed after a busy day. McLean was convinced they would grow old together.

The couple was a welcome addition to the exclusive neighborhood in Dover. Tuerk was happy to dispense medical advice to neighbors in need and help set up doctors’ appointments, while McLean won hearts with the homemade cookies she left on doorsteps. In the evenings, the couple could be seen strolling up and down the streets hand in hand, along with their yellow Lab, Cooper. As one neighbor observed, they were “like the perfection of suburbia.”

The house at 29 Valley Road had among the most perfectly manicured lawns on the street. / Photo by Matt Kalinowski

Not everything at 29 Valley Road, though, was as perfect as the lawn. Neighbors Rick and Nancy, who asked not to have their last name appear in print, say McLean told them that one day when Tuerk opened a closet and found the shelves disorganized, he pulled everything out and ordered McLean to put it all back neatly. When McLean wasn’t keeping up to his expectations, he’d forbid her from using the G-Wagen and tell her to take his Jeep instead, clients said, and some days he wouldn’t let her drive at all.

Tuerk was known to combine his hard discipline with condescending remarks and controlling behavior. McLean was no wallflower—she could hold her own in an argument, and was known to have a jealous streak herself—but his words got to her, her clients said. According to an interview she later gave to the police, McLean said Tuerk also used her iPhone’s tracking app to monitor her location, made regular calls to check in, and demanded to see her phone to find out who she had been talking to. Combine that with the video cameras installed throughout the house, and McLean felt like she was being constantly surveilled. Once, she said in the police interview, Tuerk asked her to print out her incoming and outgoing call list, and then dialed every number. McLean had an enviable figure and was fond of running 5Ks, but now Tuerk started monitoring her weight as well, according to news reports. Harrington saw a noticeable change in McLean after she got involved with Tuerk: “Her makeup was runny and her hair wasn’t as well kept. It was like her energy had been sucked out of her,” she said.

Meanwhile, McLean told her clients, Tuerk was struggling with anxiety and took a leave from his job in May 2019. There were times, she confided, when she found her motorcycle-riding husband curled up in the fetal position crying. McLean assumed he was reeling from the death of a patient and was committed to supporting him no matter what happened.

Later that month, as McLean told her neighbors, Tuerk went on a trip to Germany and McLean found herself alone in the big house on Valley Road, wondering against her better angels whether there could be other reasons for her husband’s deteriorating mental health. She knew Tuerk kept a vault hidden in the house—what could be in there? Unable to resist the temptation, she cracked it open and came across something unexpected: a trove of documents detailing a malpractice lawsuit. She also discovered papers related to an investigation by the attorney general’s office alleging that Tuerk had charged Medicare more than $31,000 over a six-year period by writing off patients’ visits with medical residents as if he had seen them himself, and had billed for ultrasound services he never performed. “I started to see [someone] I never knew,” McLean told her neighbors.

Around the same time, McLean and Tuerk’s relationship started to take an even darker turn, McLean’s clients say. Still, she felt that her nurturing and gifts as a healer would pave the way for things to get better between them. She even treated Tuerk with Reiki to ease his stress.

As summer turned into fall, this would prove a bigger challenge than she thought. In November 2019, Tuerk settled with the AG’s office, agreeing to pay a $150,000 fine, and was fired from his job at St. Elizabeth’s. His professional fall from grace made a bad situation even worse at home. In December, McLean said during her interview with police, she and Tuerk were in the bedroom arguing when Tuerk allegedly grabbed her, smashed her head into the headboard, and put one hand over her throat and the other over her nose and mouth. She closed her eyes and everything went black. When she snapped to, she screamed so loudly that one of the children heard her. She texted some of her close friends that before she closed her eyes, all she saw was Tuerk’s face full of rage. “I thought honestly he wanted me dead,” McLean later said in a text to one of them.

Tuerk apologized profusely. He told her he loved her and they had sex twice, according to McLean’s interview with the police. The following week, Tuerk took McLean on vacation to Las Vegas. When she stepped off the plane, Tuerk surprised her with a Nevada marriage license, finally making good on his proposal from more than a year earlier. McLean saw it as an apology for his violent outburst the week before. They went to a Vegas chapel, in the neon glare of the strip, and had a drive-through ceremony that came with poker chips as souvenirs.

When the newlyweds returned home, things were different, but not in the way McLean had hoped. Tuerk wasn’t working anymore, and he wasn’t sleeping either. McLean told her neighbors how he would wake up at strange hours and lift weights in the basement gym. He drank whiskey during the day and rarely showered. On January 11, after McLean shut her phone off during a massage, she came home to find Tuerk waiting for her in the doorway accusing her of “fucking around.” According to McLean’s interview with the police, he wrapped his arms around her 5-foot-8 frame, picked her up, and dropped her on her back. She hit the floor so hard that her shoes flew off her feet. When McLean asked why he had thrown her to the floor, Tuerk said he hadn’t; she simply must have slipped from his embrace.

McLean started to ask herself what she was doing to provoke him. This was not the first violent relationship she had been in. Maybe it was her fault, she suggested in texts to friends. Maybe there was something she did to inspire violent behavior in men. Maybe he didn’t know his own strength when he was drinking.

After the tumble on the floor, she could barely walk, but she hesitated to report her husband to the police. By then, Tuerk’s settlement with the attorney general had made the news, and McLean worried that additional bad publicity would prevent Tuerk from finding another job.

The violence only continued. Later that month, McLean told police in her interview, while she sat working on a school project with her youngest child, Tuerk said, “I’m the fucking king of this castle; you are only a guest,” before leaning in to cut a lock of her red hair. McLean reached up to stop him and the scissors struck her, sending a rivulet of blood down her hand.

McLean was growing increasingly worried and was unsure how much further her husband would go. She told the police that after one argument, she heard the electronic tones of Tuerk entering a key code into his gun safe, where she knew he kept four firearms.

Then there was the couple’s Super Bowl Sunday party. Though McLean greeted the guests with her usual smiles and cheer, later, when Tuerk left the room, she told some of them that she might not be able to stick it out in her marriage for much longer. Tuerk overheard her. After the guests left, McLean said in her police interview, she decided to walk over to Tuerk and sit on his lap. But the moment of affection quickly turned dark as Tuerk called his son downstairs and, as he looked on, unceremoniously pushed his wife to the floor. That was the last straw for McLean.

The very next day, McLean drove a few short minutes to the Dover Police Station, a building painted deep red in the spirit of a rustic barn. She was disheveled, the screen of her iPhone was shattered, and she was crying. McLean told officers at the front desk that Tuerk had been violent, and she was filing for divorce. She didn’t want to press charges; she just wanted them to know—in case something happened to her. Sergeant Ryan Menice took one look at her and told McLean they should have a talk. The heavyset man with kind eyes offered McLean a sea-green swivel chair in the conference room at the back of the station. McLean was reluctant at first, but as Menice pulled out a notepad, she walked him through the horrors of the past few months.

When McLean mentioned the gun safe and the strangulation, Menice suspected he had a serious domestic abuse case on his hands. The term “battered woman” often conjures images of black eyes and bruises, yet strangulation or choking, particularly in the way McLean claimed Tuerk stopped her breath, by placing his hands over her mouth and nose, may not always leave a mark. This is unfortunate, because non-fatal strangulation is one of the most reliable warning signs that domestic violence may escalate to murder. According to the work of psychologist David Adams, author of Why Do They Kill?—a study of men in Massachusetts who have slayed their intimate partners—Tuerk checked off two more boxes: He owned guns, and according to text messages McLean sent to her friends, she believed he was capable of killing her.

Menice told McLean that she should think about filing for a restraining order immediately, and that police needed to seize Tuerk’s guns. McLean just wanted the problem to stop, but Menice kept urging her. “You have kids,” he told her. “You don’t want to end up dead.” Mentioning the children was enough. McLean agreed to do it.

Climbing into her Jeep, she followed the sergeant to Dedham District Court since she couldn’t see her GPS instructions through her broken phone screen. Menice told McLean to come back to the police station when she was through, at which time the officers would enforce the order.

Menice had just returned to the station to start the paperwork detailing McLean’s allegations when he says a tall, well-built man walked through the door. It was Tuerk. He said he had come by because he was worried his wife was going to make false accusations against him. In his interview with Menice, Tuerk said McLean was the jealous and controlling one, not him. He had never been violent. He was the one who was leaving her. Menice took notes and Tuerk left.

Meanwhile, a judge signed off on McLean’s abuse-prevention order, but instead of returning to the Dover Police Station, as Menice had instructed her, McLean drove back to 29 Valley Road to show Tuerk the order herself. This was not part of the plan. When Tuerk refused to leave the house, McLean called Menice in a panic.

“He won’t leave,” she told him.

“Get out of the house now,” Menice told her.

McLean quickly did as he said while Menice and his fellow officers scrambled into their squad cars and raced over to Valley Road. Tuerk met them in the driveway, bending over and putting his hands on his knees like he was trying to catch his breath. “Do you have to do this?” he asked. He was just trying to provide a nice home for McLean and her children, and now he had to leave? He sure did, the officers told him before accompanying him to his gun safe so he could turn over his weapons.

Under the watchful eye of the officers, Tuerk collected his belongings and left the premises. McLean breathed a sigh of relief. But even from afar, Tuerk found ways to torment her. McLean’s neighbors say he canceled the bottled-water service and had the company pick up all of the unused water that had already been paid for. Court documents show that he also attempted to seize the Jeep, at that point the only car to which McLean had access. It wasn’t until she reported to the police that Tuerk used the Nest thermostat to turn the heat down, making the house unbearably cold, that he violated the terms of the abuse-prevention order and was arrested.

Still, this infraction, plus assault charges filed against Tuerk after McLean reported him to the police in February, were of little comfort to McLean, who worried that Tuerk might retaliate. According to her police interview, McLean said he once told her about a patient who offered to have one of Tuerk’s ex-wives killed. They laughed about it at the time, but it wasn’t so funny anymore. After Tuerk was released on bail, she told her clients, the garage door would open at strange hours and McLean wondered if it was Tuerk driving by with the garage remote. She also told her neighbors that she sensed she was being followed. McLean was left with the disturbing realization that she may have gotten rid of Tuerk, but she was not rid of the fear that he could harm her.

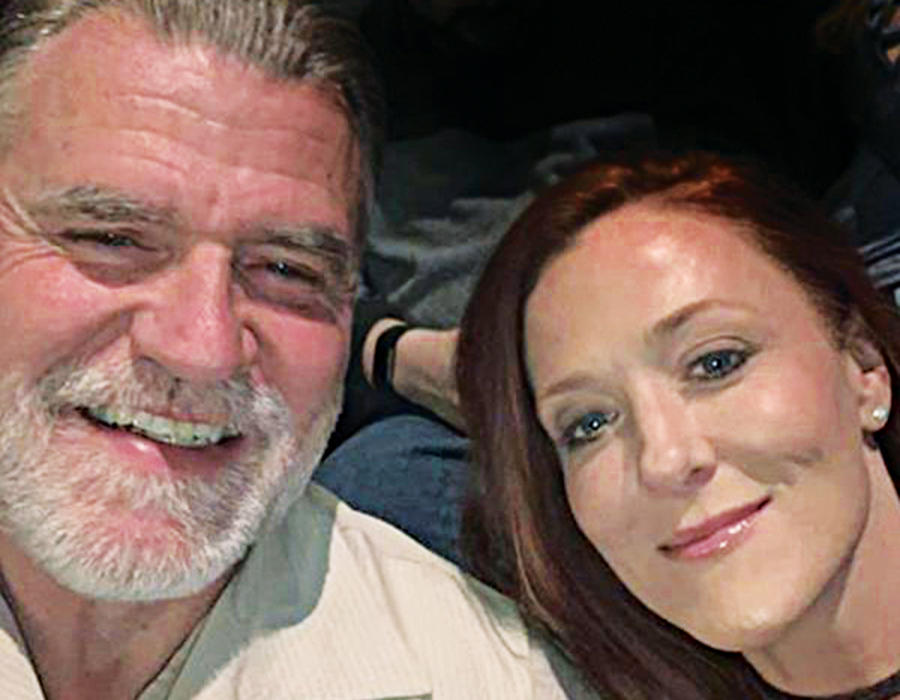

Ingolf Tuerk and Katie McLean in better times looked like a happy suburban couple. / Photo via Facebook

On a Thursday afternoon in late February, McLean walked across Valley Road in her bathrobe and fuzzy moccasin slippers and knocked on the door of Rick and Nancy’s house. She was shaking. “I don’t know how to say this,” McLean began. Nancy sat her down on the sofa, and McLean told them everything.

“She was like a slave,” Nancy thought to herself, cleaning all day long.

“Are you frightened for your life?” Nancy asked.

“Yes,” McLean told her.

“Please, Katie, don’t live here. Can’t you move away?” Nancy begged.

McLean said she didn’t want to uproot her children again; she desperately wanted them to finish school in Dover. She just wanted Rick and Nancy to keep an eye out and call the police if they ever saw Tuerk approach the house.

Around that time, when McLean was chatting with a client on the phone after giving her a psychic reading, she mentioned the turn of events in her relationship with Tuerk and the secrets she’d discovered. Tuerk’s claim that he was an alternate for East Germany’s 1980 decathlon team—which was repeated in the St. Elizabeth Medical Center ad—was not right, she told the client. (Siegfried Stark and Steffen Grummt, two of three members of the actual 1980 decathlon team for East Germany, say they do not remember Tuerk.) “It’s so weird to be able to see things so clearly in other people’s lives all the time,” she said. “And then in my own life, I’m like, I don’t know.”

In the months that followed, McLean managed to find a modicum of peace while quarantining with her kids. “I have found such a deep gratitude for my children it’s amazing,” she wrote on Facebook. “This has been one of the most beautiful cleansing, healing times of my life…seeing my children laugh, dance, learn and play together every day (sometimes argue but rare!) takes me back to the early days staying at home with them and just enjoying who they are…. I have had some of the deepest conversations with my teenagers and laughed until I’m in tears!”

On Easter weekend, the house finches began to build a nest out of pieces of hay collected from the decorative stack McLean kept on the front lawn. She decided to watch the birds with her children as a school project. “We are so excited to watch the eggs, hatch, grow and take flight,” she wrote. “Just like me watching these three.”

As they watched the birds create their nest, McLean and the children’s time on Valley Road seemed to be coming to an end. In probate court, a judge had ruled that Tuerk could put the house on the market and she and the children could be forced to leave as early as July. It didn’t matter that McLean had put most of her savings into renovating the basement, the new pool, and the gazebo with a fireplace and flat-screen TV. It didn’t matter that when the shutdown came, McLean could no longer see clients there. “The house is being listed soon, sadly. The girls just want to finish high school here. They were almost done. It’s sad to leave friends, sports, church and school,” McLean wrote to Nancy and Rick in a text message.

In early May, Rick was checking his mailbox when he bumped into McLean at the end of the driveway. She offered some surprising news: She and Tuerk were going to be getting back together. She explained that Tuerk was receiving intensive therapy and was having a breakthrough. She was excited that her children would be able to finish their education in Dover. On May 4, 2020, McLean, in her neat, loopy handwriting, requested that the abuse-prevention order against her husband be removed. “I feel safe with him and trust his intentions to reconcile our family and marriage,” she wrote in documents filed in court.

This decision is not uncommon. According to Hema Sarang-Sieminski, policy director at Jane Doe Inc., an organization that works on domestic violence issues, it takes a victim an average of seven attempts to leave an abusive domestic partner for good. Sarang-Sieminski says there are myriad reasons why survivors might elect to resolve the issue outside of court, including the fear of retaliation, financial and social pressures, and the fact that “a person who causes harm in this way is very skilled at capitalizing on all of the fears that a survivor might have.”

McLean’s request was successful, and the judge agreed to drop the abuse-prevention order. The judge would not dismiss the criminal charges, though, and Tuerk’s bail conditions still required that he stay out of 29 Valley Road until the case was resolved. Tuerk, apparently, was not concerned about that. On the evening of May 14, 2020, he went home.

On the morning following Tuerk’s homecoming meal, when the children couldn’t find their mom, they called their father in Waltham. As he drove to Dover to check on them, he was getting worried calls from Katie’s friends, who had gotten wind of the weird text Tuerk had sent. When the children’s father arrived at the house and Katie still had not come home, he called the police.

According to police affidavits, officers went to the Residence Inn in Dedham, across from Legacy Place, where Tuerk had been renting a room on and off since the separation. Pulling into the parking lot, they noticed that both Tuerk’s G-Wagen and McLean’s Jeep were parked outside. It looked like the couple was there together.

The officers knocked on the door of the room registered to Tuerk and called out his name, according to the police affidavit. No response. Increasingly concerned, they asked a hotel clerk to open the door with an electronic key. Inside they found a disturbing sight: the doctor bleeding on the white hotel sheets. There was a cut on his head, a self-inflicted laceration on his left wrist, and scratches on his legs. But there was no sign of McLean. Tuerk, who appeared to be unconscious, was rushed to Norwood Hospital. He would not wake up for more than 24 hours.

Meanwhile, the search for McLean kicked into high gear. State troopers assigned to the Norfolk County District Attorney’s Office entered the home at 29 Valley Road and forced open the locked bedroom door to find the floor covered in broken glass. McLean’s purse and cell phone were inside. Sergeant Menice, who silently hoped she had fled to a friend’s house in a hurry, says he contacted just about everyone she would have been comfortable asking for help. No one had heard from her.

The scratches on Tuerk’s legs looked a lot like he could have gotten them from bushwhacking, so for the next day and night, officers and their search dogs combed the 595 acres of the Noanet Woodlands reservation, which was less than two blocks from McLean and Tuerk’s house. They came up empty.

Finally, in the late afternoon on Saturday, Tuerk stirred his massive frame and opened his pale blue eyes to find himself handcuffed to a medical bed surrounded by a gaggle of doctors, nurses, and detectives who wanted to know what he had done with his wife. According to the commonwealth’s statement of case, Tuerk initially said he had only spotty recollections of Thursday night and did not know why he was in the hospital, but eventually conceded that his memory was starting to come back to him. A state trooper recorded the conversation while Tuerk waived his Miranda rights and confessed.

He told the officers that when he and McLean went up to the bedroom after board games with the kids, they were drinking and arguing over text messages. She threw a glass at his head, and he wrapped his hands around her neck and strangled her. It wasn’t until she died in his arms, he said, that the doctor realized he had gone too far.

Where was the body? asked the troopers.

Tuerk said he couldn’t remember.

Her family needs closure, they said. Where is she?

Tuerk told the officers about the vacant lot near his home, next to a newly constructed mansion that had not yet sold. A half dozen troopers and Dover police officers descended on the address Tuerk provided. It was dark when the officers began climbing over trunks of fallen trees to search for McLean. A trooper scanned his flashlight over the clearing, finding a dark, murky pond, and spotted something white roughly 15 feet from shore. It was McLean. She was lying face down, wearing only her yoga pants, which had been weighted down by rocks. A dive team untangled her from a bed of waterlilies, and the officers carried her body out of the woods in a tarp.

Neighbors were shaken as details about McLean’s death surfaced in the news: According to the medical examiner’s report, the autopsy revealed McLean had a fractured neck bone, bleeding in both eyes, bruises on her neck and within the neck muscle, and bruising on her scalp and brain. The cause of death was determined to be strangulation and the manner homicide.

McLean’s cremated remains were buried in a private ceremony restricted to immediate family because of the pandemic. Meanwhile, her death became yet another depressing pandemic-era statistic. McLean was one of six women in Massachusetts killed by their domestic partners since the onset of COVID-19, according to Jane Doe Inc. Of those six homicides, half were murder-suicides, cases in which the perpetrator took his own life as well. The other half were attempted murder-suicides, incidents in which the alleged perpetrators apparently attempted to take their own lives, as Tuerk is accused of doing.

While shelters and hotlines in Massachusetts are reporting a decrease in calls from domestic violence victims, experts believe that the decline is not the result of a decrease in assaults, but rather because victims are unable to get away or even find enough privacy to call for help. A new report from the radiology department at Brigham and Women’s, for instance, found a nearly twofold increase in cases of severe injury among abuse survivors who seek medical services. As Sarang-Sieminski says, a strong social network is one of the most crucial forms of support for survivors in distress, and COVID-19 is isolating survivors.

This was the first official homicide in Dover in recent years, yet the abuse that preceded it is not uncommon. In fact, Menice says, he has another recent domestic violence case involving strangulation, albeit non-fatal. “Everybody’s like, it’s Dover, nothing happens in Dover,” he says. “Well, stuff happens in Dover.”

On May 18, Tuerk faced a judge over video for a virtual arraignment, wearing an orange jumpsuit with a facemask around his chin. Despite his hospital-bed confession, he pleaded not guilty and was ordered held without bail at the Norfolk County Jail. Tuerk’s attorney, Kevin Reddington, declined to comment on any allegations against Tuerk with regard to McLean’s death or their relationship prior to it. He would only say that McLean took out the restraining order so she could use it as leverage to get Tuerk to put her name on the deed. He said he will seek an acquittal for Tuerk when the case goes to trial.

The house at 29 Valley Road has stood empty since the morning McLean’s children discovered she was missing. The neighbors have chipped in for landscaping expenses in an attempt to keep up appearances on the leafy Dover street, but no one is watering the grass and it has turned brown and brittle. The backyard is overgrown with thistles. In late summer, all that remained of the nest of house finches that became McLean’s science project with her children, and her omen of good fortune, was a streak of dried bird droppings across the front door.