Charlie Baker: Leadership, Lessons Learned, and What Lies Ahead

After 13 months of managing the COVID crisis, the governor opens up about “one of the most difficult things” he’s ever been through.

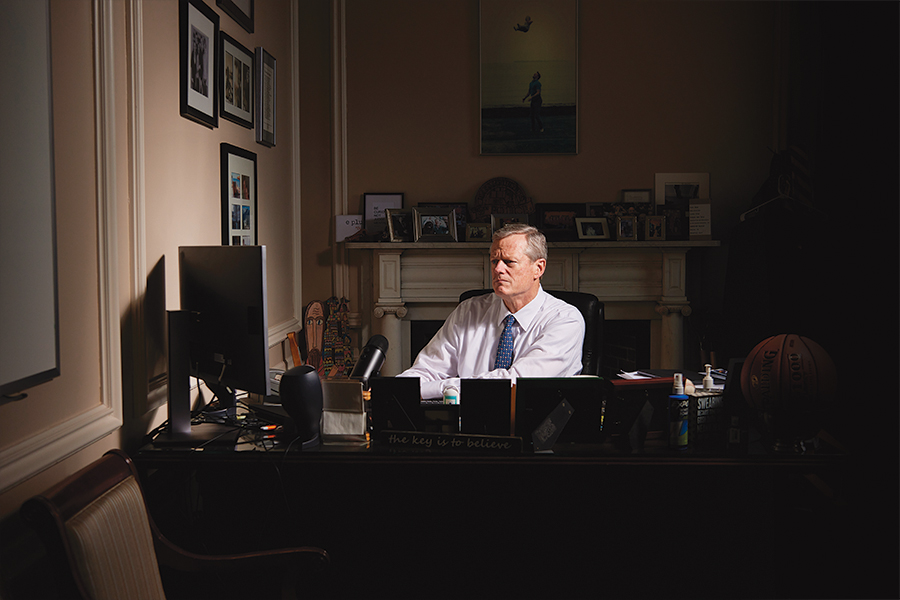

Governor Baker gets to work in his private office; on a typical day during the pandemic, only a handful of staffers join him in the State House. / Photo by Ken Richardson

“It’s nice to see you,” Charlie Baker says, walking toward me and bending his long right arm so his elbow points in my direction. I stand up and raise my own elbow—the 6-foot-6 governor has a good 8 inches on me—and after a quick bump the two of us move to opposite ends of a conference table.

We’re in Baker’s ceremonial office at the State House, and it’s only a slight exaggeration to say it feels like we’re the only two souls inside this gargantuan building. On my way up to the governor’s third-floor suite, I glimpsed exactly three people—all security guards—and inside I’ve seen only one other person, a press aide. The mix of people who typically make this building bustle—state legislators, cabinet officials, staffers—left nearly a year ago, and most haven’t been back since.

Even the office—a high-ceilinged, ornate space—hasn’t been spared from the realities of the pandemic. Directly in front of a beautiful wooden desk stands a cart supporting a large-screen TV, teed up for yet another Zoom meeting. COVID, it seems, leaves its mark in strange ways.

As for Baker himself, he’s dressed the way we’ve gotten used to seeing him over the past six years: gray suit, white shirt, blue tie, requisite flag lapel pin. But he’s the first to note that his hair is grayer than it was last spring, and as we launch into a conversation about the year he’s had—shutting down the economy, searching for PPE, rolling out a vaccine plan—it’s clear the governor is reflective and a little weary about what we’ve all been through.

It was really interesting to walk into this building and see how quiet it is.

It’s like working in a mausoleum.

How has the pandemic changed the way the office operates? How many people are actually here?

I don’t know, there might be four people here? Five? [Deputy communications director Anisha Chakrabarti confirms that there are five people in the office today.]

There are some people who haven’t been in since last March. My assistant hasn’t been in since March. Most people who work in the executive branch who can work remotely have been working remotely since the beginning. Now, that required a whole bunch of two-minute drills to figure out how to make a lot of the infrastructure we have actually capable of playing in a virtual world.

We created an Executive Office of Technology Services and Security because we didn’t really have a chief information officer for the commonwealth when we got here. Most of us were thinking about it as a way to create standards and infrastructure around [cyber] security. And it’s worked really well on that. But one of the best parts about it was that we had an actual center of gravity when all of a sudden everybody needed to work remotely—whether you had to get people devices or put routers and infrastructure in buildings to make it work, so you can put 65 people on one of those things. [Points to the big-screen TV.]

But there’s a lot of people who—I mean, if you walk around in the administrative offices, there’s a lot of places where it’s pretty clear no one’s been there for almost a year.

What about you? Have you been here most days?

I work from home a few days. But I come in most days. We do meetings where there will be five or six people around here somewhere, and the meetings are [still] done virtually or they’re done as conference calls. My real office is down the hall. No one comes in there. No one. No one goes in the lieutenant governor’s office. No one goes in [chief of staff] Kristen Lepore’s office. We just don’t do that. We used to have cabinet meetings every Friday upstairs on the fourth floor. Now it’s a Zoom call. A bunch of those cabinet secretaries I’ve only seen in two dimensions for a long time. Occasionally we might do some event, and I see them and we joke about the fact that we all look a little older and a little grayer.

But I think that’s fairly common. There are people who work for the governor’s office who I’ve never met. We did a big Webex call for Christmas. Like, put a fire in the fireplace; I sat on the couch. And I’m looking at these faces, and I’m literally saying out loud, “Half of you, honestly, could you introduce yourself and tell me who you are, because I’ve never seen you before.” One of the greatest challenges all organizations have now and in the future, living in this kind of a world, is how do you socialize people into your organization? How do they develop real personal relationships, which are important around team building, with people they’ve never spent any time with except on a conference call or a virtual meeting? I think it’s hard.

I agree. Because in a virtual meeting, there’s not very much chitchat. It’s very transactional, as opposed to in an office setting, where there’s lots of small talk—“How was your weekend?”—that kind of thing.

There’s a lot of learning that happens in those chitchats. And they don’t happen very much anymore. It’s certainly one of the things I miss a lot. And I know it’s something a lot of other people miss.

I have to tell you quickly: I got up this morning and put this suit on. And it occurred to me I haven’t worn a suit in a year.

Do you wear the top sometimes and not the bottom?

[Laughs.] No, I don’t think anybody really cares what I’m wearing these days.

I gave my State of the State right there. [Points to a spot a few feet away.] I wanted to give my State of the State from there with my suit on, my coat and tie and all the rest, and then I wanted to walk away from the podium and be wearing pajama bottoms and slippers. Which I thought would have been 100 percent consistent with what everybody’s been doing for the past year. I got told that that was not very gubernatorial, so I didn’t do it.

That’s hilarious.

But, you know, the flip side of this is: The job never leaves you, right? In the old days I’d leave the house at 6:30 in the morning. I’d go to a breakfast somewhere, I’d come in here for a couple of meetings, I’d make some phone calls, then I’d go someplace to give a talk to somebody at lunch. Then I’d come back here for whatever we were doing in the afternoon. And then I’d go out and do three or four things at night, which were actually my favorite part of the job, because I would go to all these really cool organizations that were doing neat things, and I’d get a chance to meet them and all the rest. And I’d get home around 9:30, 10 o’clock and I would go [brushes hands together]—done. Now there’s no separation between working and not working. I was on the phone almost all day on Saturday and Sunday. I did go visit my dad Sunday. But that was about it. And I’m sure it’s the same for you guys. You’re sort of always available now. Have you been in the office?

No, I haven’t.

It’s gonna be interesting to see what happens when the dust all settles. I’ve been asking almost everybody that I deal with on these calls: “Folks, show of hands, how many people want to go back five days a week?” Practically nobody raises their hands. “How many people don’t want to go back at all?” Nobody raises their hand. “How many people want to go back one, two, three days, something like that?” Every hand goes up. People have adjusted. They really have.

Governor Baker (center) attends to business in the Council Chamber with senior adviser Tim Buckley (left) and communications director Lizzy Guyton (right).

You’ve been getting heat over the past few weeks because of the vaccine rollout. Does the criticism feel fair?

I don’t think when you’re dealing with an issue like a global pandemic—it’s a horribly rocky road for everybody who’s affected by it, no matter what you do. I read an article, I think in the Wall Street Journal, about Arne Sorenson. He was the first non-Marriott family member to run Marriott. He just died of pancreatic cancer. But the article talked about the agony he went through when he had to lay people off and furlough them. He did a big town meeting of all their employees—which apparently went viral—where he broke down and wept about what he had to do. And I’ve talked to a lot of folks in business generally who’ve said, “I didn’t get any smarter, I was just on the right side of the COVID curve.” And I’ve talked to other people who’ve said, “I don’t think I got any dumber, but I was on the wrong side of the COVID curve.” Every day I talk to people and come in contact with people for whom this past year has been like no other. So I don’t think about my own job in the context of whether I have a rocky day or a not-rocky day. We try to make the best decisions we can based on the best information we have.

We started slow on the vaccine rollout by design. Because we chased a whole bunch of populations that are hard to get to and no one usually pays any attention to when it comes to this stuff. We got off to a slow start because of that. But the metric that most people seem to measure this by is, “How many people have you dosed?” So we got pretty aggressive over the course of the past three weeks. And we’re now number one in the country in terms of doses per capita for the top 24 states based on population.

You’re going to get criticized and supported on almost every decision you make. And in the course of the past year, just because of the brutality of COVID generally, all of that has come with tremendous anxiety. And I completely get that.

Let’s back up to a year ago. When did the coronavirus first come on your radar, and at what moment did you realize it was really a big deal?

Keep in mind that we had the kid from Wuhan who came back, who basically isolated himself, reported himself, got tested multiple times. [Massachusetts announced its first confirmed COVID case, a UMass Boston student, on February 1, 2020.] Never showed any symptoms—we all could have learned something from that. And so at the same time he’s here with us, and we’re all paying attention to him, there’s this drib and drab of stuff that’s starting to come out of China. And then it starts to roil a bit in Italy. And then there’s Biogen. Biogen involved conferees who were from Italy and Switzerland. And the way we found out about [the virus spreading at] Biogen was from a guy who’s from Philly who got diagnosed in Philly,

contact-traced back to here, and then everybody started pulling the cord on what was going on with Biogen. I think that was when a lot of people realized the contagiousness of this and the potential for spread. It was shortly after that that we issued the emergency order and closed down the bars on St. Patrick’s Day and the restaurants, and then eventually the economy and the schools.

It was March 10 when you declared a state of emergency. In your head, how long did you think this was going to go on? As a layperson, I remember assuming, Oh, we’re going to have to hunker down for a few weeks to get through this, then we’ll be fine.

One of the biggest challenges as a public official in this whole thing is the variety of opinions that are out there. I think a lot of people were actually saying we’d see how things were after April [school] vacation. But, at the same time that was going on, Anthony Fauci was saying things like, “We’ll get through this, but we will be changed by it.” And I remember when I heard him say it—that doesn’t sound like April school vacation. That sounds like a bigger deal than that.

The states barely got any support from the federal government during the pandemic. What are your thoughts about that?

Certainly the PPE issue, straight out of the gate, was a big deal. I mean, the feds have tremendous capacity to generate product of any kind, far more so than states do. States have to go buy it. The feds can order people to make it. We can’t do that. On some of the testing stuff, there was a very long period of time that we were waiting for the CDC to give us a test we could use. And that put, I think, a lot of our effort to get in front of this and to start to identify people and to deal with a lot of those issues farther behind than we wanted it to be. We got there eventually, but it took a while.

Governor Baker speaks to the camera in the Ceremonial Room, which has been turned into a “web fortress” for Zoom meetings. / Photo by Ken Richardson

This became political pretty quickly. How much do you hold former President Trump accountable for that?

There were plenty of people working at the federal level trying to figure out how to keep the politics out of it, but that was made very difficult by what was coming out of the White House. One of the things public officials need to do, for better or for worse, when they get into a situation like that is to try to make sure that whatever you’re sharing with people—because they are listening to you like they never listened to you—is something that’s been pretty well vetted and pretty well tested so you’re not sending people off on some path that doesn’t make a lot of sense. I’m much better about being scripted now than I probably was 10 years ago when I first ran for governor. I understand and appreciate the importance of choosing your words carefully. I think some of the stuff the president said—especially the off-the-cuff stuff—really complicated all of the messaging that anybody was trying to get out there.

I think back on the daily briefings he was giving. You tuned in just to see what the heck he was going to say today. It’s not something to laugh about, but that was the tenor of those things.

When people are scared, they watch. We got oceans of mail in here from people who watched [our briefings]—I think we did like 90 or 100 days in a row. People watched. We got all kinds of incoming online and snail mail from people talking about very particular things that we talked about in our press availabilities. I came to realize that this thing was like: Charlie Baker’s COVID briefing at noon was more important than The Price Is Right. And for me, it was kind of a surprise. I never have any idea how much of what we say or do around here actually gets to people. But it was very clear to me that on this stuff, people were paying attention in a big way.

You have a background in the healthcare world. Was that helpful over the past year?

I definitely believe that the trust thing makes a difference when you’re trying to get somewhere with a group on a complicated issue. Whether you’re talking healthcare institutions or people in the biotech space or whatever it might be. I’m sort of a known quantity in that world, and I know a lot of them. So it’s just a much more personal back and forth, which can be really helpful when you’re trying to collect data and gather information and make decisions.

You’ve gone through the pandemic in two ways: as the person leading the state and just as a guy. You mentioned your dad before. You said back in the spring that you used to have dinner with him every week and now haven’t been able to see him as much. How have you dealt with that?

I used to see him just about once a week. I had a meal with him at least three or four times a month. Sometimes my wife came, sometimes my kids came. It was just a cool moment for us to catch up and get together. And when all this happened, I didn’t see him for a hundred days. And I’m not really very good on the phone, unless it’s work-related. And he’s not very good on the phone at all. And so we didn’t talk—it was bad.

It got a little better once you could go visit, but you know, we weren’t going out for a meal. I couldn’t give him a hug. I mean, I get the safety protocols and all the rest. But I really believe they have been very tough—just watching my own experience with my dad and my brothers with my dad. There’s a big human element that COVID takes from us, and it’s not just in those kinds of environments. It’s around almost anything that involves gatherings and groups. Churches. Concerts. All that stuff. And it’s a huge loss.

I also mentioned in the spring—somebody asked me about it—my best friend’s mom died. And they did not have the ability to say goodbye…[pauses]…in the way you’re supposed to be able to do that. And I think in some respects, some of the cruelest things about COVID relate to the fact that it pushes people away from each other. And if it does that to all of us for a short period of time, that’s one thing. But you know, when you’re going on a year…for a year, I haven’t seen my dad without a mask on, and I haven’t given him a hug, and I haven’t been within 6 feet of him. I mean, it’s just pretty lousy, all around.

I want to ask you about your decision-making process. You have a reputation as a good manager. I’m curious how you make decisions. Are you someone who absorbs input from a large group of people? Is it a small circle? Do you decide quickly, or do you need time to meditate on things?

You probably won’t like this answer. The answer is, it depends. There are some decisions where you would like to have more time, but you don’t, and where you’d like to have more information, but you don’t. To the extent that we could, we tried to put structure in place with people who knew something about what they were talking about so that we would make better decisions even if we had to make them quickly.

The whole reopening group we put together—that had local officials, businesspeople, and healthcare people. I really wanted the healthcare people to listen to the employer community about what their concerns were and what they were trying to do, and vice versa. Because if they heard each other, what we could get out of that is public-health people thinking about the problem some employer was trying to solve on their terms. And at the same time, the employer would be hearing from the healthcare person about why guidance, safety, rules, structure, and modification are important for the health of your workforce and your customers.

In the end you want to be able to get information from enough people who know what they’re talking about so that when you do have to make decisions, it’s not the first time you’ve ever talked to them; you have some rhythm where there’s some kind of a dialogue in place. But sometimes you just have to make decisions.

The decision around bringing in the National Guard to do all the testing at the long-term-care facilities, that was literally like, “Asymptomatic spread is real, we have a big problem, we just have to do it.” And then the whole decision around the emergency order and the shutdowns—those are the kinds of decisions that are so big and so difficult, you would love to have a few more people to talk to. But you don’t have any time.

Is that the kind of situation where you’re lying awake at 3 o’clock in the morning, saying, “What am I going to do here?” Have you had any of those moments?

I have them all the time. My wife will be the first to tell you, I was not that gray for my age at the start of all this. And I sure am now. I think this has been—and I don’t think I’m just speaking for me, I think this is true for almost anybody who’s in a public role—it’s been the most difficult thing I’ve ever been through. Because the information constantly changes. It’s not always clear what the right answer is. It’s not always clear when the right time to make a decision is. And generally speaking, when you do make one, you’re going to have people on both sides say it’s the wrong decision.

Do you ever think, If I’ve annoyed both sides, I’m doing the right thing?

I think more of it is about believing that you are doing the best you can to make the best decision at the time based on what you know. And if you learn a whole bunch of things, you need to be willing to change.

We’ve made a million decisions over the course of this where we’ve changed what we were planning to do and gone in a different direction.

You’ve been outspoken about Donald Trump over the years, and he’s fired back. Does it mess with your life in any way when you’re on the receiving end of a Trump tweet?

[Long pause.] I don’t think so. I think the most difficult of all of the politics of this—for me it’s much more about, you know, the mail. And it’s not the letter that somebody writes that says, “You’re a horrible person, I hate your guts.” It’s the person who writes me a letter that says, “My family’s owned this business for a bajillion years. We survived the Depression, World War II, and because we’re on the wrong side of that COVID curve, your rules are making it impossible for us to operate. This is what we are, it’s who we are, it’s what we’ve done—and it’s your fault.”

That hurts so much more than the back and forth of political…whatever. Because it’s real people who are being put in an impossible position through no fault of their own because of the combination of what COVID is and what the public-health people are telling me I need to do to deal with it. The letters I got from families about kids—special-needs kids—oh, my God. So much more intense than the politics.

[Very quietly.] The thing that always gets lost in a lot of this stuff is…there’s what’s going on on TV and in social media and in the political sphere—figurative hand-to-hand combat of one kind or another. Most of those folks are still going to have their jobs and still going to pay their bills and still going to have their houses and all the rest at the end of the day. So for me, the stuff that sticks and stings is just regular people who again, through no fault of their own, have just had their lives turned upside down and inside out.

Most of the people who work in government, we get into it because we want to help people have better lives. And it’s really hard to explain to somebody—Why are we doing this over here when they see what

it’s doing to them over there? And I am completely sympathetic and moved by what’s going on with them. This whole thing is, I mean, it’s theater for some. It’s real life for everybody else. And you know, that gets lost sometimes.

Read more about what’s next for Boston