Without an Official Vaccine Mandate, Boston Bars and Restaurants Are “Taking Matters into Our Own Hands”

The service industry is on a new front line of public health—and some are hoping for backup.

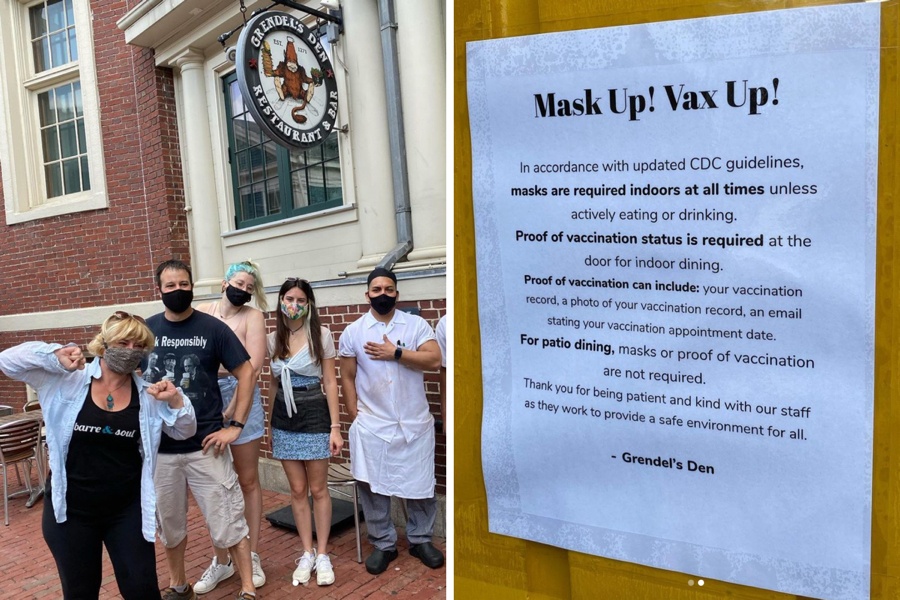

Photos via Instagram/Grendel’s Den

It’s after quitting time, and you’re thirsty for a pint at the local watering hole. Do you know where your vaccine card is?

Or maybe you’re headed out to see your favorite band. Have you checked if the venue has gone vaccinated-only? Will a negative COVID test suffice?

New questions, caveats, and bouts of confusion are sweeping Boston right now, as a growing cohort of bars, restaurants, nightclubs, and businesses of all kinds are rolling out new vaccine restrictions. In New York, this paradigm shift has been mandated by the city: As of September, New Yorkers will be required to show proof of vaccination on a city-run app to visit indoor venues. But in and around Boston, where officials have yet to similarly impose a top-down directive, the unhappy task of determining whether (and how) to separate the vaxxed from the un-vaxxed is being left to the businesses themselves. The question is: Should they—and by extension, the rest of us—have to figure this out alone?

If so, it won’t be easy. For the handful of local businesses who have so far opted to reserve some or all of their services for vaccinated customers only, there’s already been a bit of a learning curve. In the absence of a state or city-run program, perhaps with a centralized app like New York’s Excelsior Pass, the management and enforcement of rules (as well as any castigation from angry customers) is falling on the already-exhausted shoulders of restaurant hosts, venue bouncers, and other public-facing staff.

“We’ve had to take matters into our own hands,” says Abby Taylor, manager at Grendel’s Den, a popular Harvard square pub that was among the first in the state to require proof of vaccination for indoor dining.

For her staff, that’s meant checking paper vaccine cards, or pictures of them, as well as navigating the multitude of vaccine-verification apps that have sprung up this year—poring over proofs of vaccination sent via email, or text, or URL. Being an early-adopter of a vaccine policy has also meant dealing with customers who are not yet accustomed to showing proof that they’ve been jabbed. They may be agitated at the hassle of doing so, especially those who insist they’ve been vaccinated but aren’t prepared to prove it in a pinch. Maybe they forgot their vaccine card at home, or misplaced it long ago, destroyed it in the laundry, or wrecked it with a spilled cup of coffee. Plenty of people have stored a photo on their phone, but struggle to find it buried amidst a jumble of pics.

It can make for some angsty, awkward, often frustrating situations at the door. “We’re basically telling staff they have to be on the front lines of this, and they’ve already been through a year of dealing with people who have all different opinions of what we should be doing,” Taylor says. “It’s a lot.”

It’s not exactly clear whether a city or statewide mandate of the kind headed for New York would make things better or worse for these restaurants, and there appears to be little appetite for such a broad solution here. Gov. Charlie Baker has yet to embrace such a mandate, and acting Boston Mayor Kim Janey made her thoughts on the matter abundantly, and controversially, clear. But the vaccinated-only restaurants I spoke with this week say they hope more of their peers follow their lead, or that officials do something—anything—to help.

For Cambridge’s PAGU, which has been requiring vaccines for indoor dining since June, the spread of vaccine-mandating restaurants could go a long way in turning down the heat from critics. While the vast majority of diners have been supportive, being early to act on this has made PAGU a target for trolls. Angry emails, nasty online comments and suspect one-star reviews have flowed in. Some have left aggressive voicemails. “Whether or not they’ve actually dined with us is questionable, but there’s all forms of hatred and comments calling us communists and saying this is a violation of their privacy rights, or that it’s discrimination,” owner Tracy Chang says. Staff are now regularly rooting out and reporting abusive conduct on the internet.

Fewer express their frustrations in person, Chang says. Typically the vaccine-checking process is pretty painless, and takes less than a minute. Unvaccinated diners (those who don’t want to eat outside, where they’re still welcome) have learned to stay away, and some vaccinated customers have told Chang they came to PAGU specifically for the sense of safety a fully-vaccinated dining room provides.

Still, Chang would rather see a unified front. She has spent the past two months encouraging her peers to enact similar policies, and she would back a top-down mandate from government. “To put the pressure on small businesses to do this themselves is obviously not insurmountable,” Chang says. “We’ve shown that it’s doable. But being an outlier as one of the very few places that do it slows us down a little bit. If there was a citywide, or even a state- or nation-wide way of doing this and people were more accustomed to it, and it was more efficient, that would be welcome. I actually think it’s only a matter of time before that happens.”

Over in East Boston, Josh Weinstein says no one had to issue a mandate for him to require vaccines at The Quiet Few. After a customer revealed they’d tested positive inside the popular whiskey bar last week, forcing it to close down temporarily—for the second time during the pandemic—”we just decided to jump into it with both feet.”

Ahead of the bar’s reopening with the new policy on Wednesday, he’d been preparing for the worst. But Weinstein says things went smoothly, and only a few people had to be turned away for having left their vaccine cards at home. Sure, having a vaccine mandate would make things “cleaner,” but he’s hoping people will continue happily complying with the new rules without needing an official mandate.

Maybe that’s realistic for a neighborhood bar. At larger ticketed event venues, though, the vaccine-checking process can be a bit more complicated, and expensive. After all, someone who has already shelled out hard-earned money for a ticket is a lot more likely to object to being excluded. At City Winery, one of just two clubs (so far) in the city to require proof of vaccination—or a negative COVID test, which is scanned and verified by one of the venue’s new CLEAR readers—they’ve taken extraordinary steps to keep from turning people away. Fans showing up to the winery’s 300-seat music hall can actually opt to take an on-site rapid COVID test, which delivers results in about 8 minutes, for a $15 fee.

It all comes at a cost—training staff, spending the extra time checking everyone at the door—but CEO Michael Dorf says it’s worth it to ensure the national brand’s venues across the country can keep the music rolling. “It’s a little extra work, and we’re all overworked, no question about it,” Dorf says. “But this is what we have to do right now.”

He says he’s hoping other large live event companies, like LiveNation, eventually come around to implementing vaccine mandates so venues like his don’t have to forge ahead on their own, and to limit the risk of another shutdown of live music.

In the meantime, for a lot of smaller businesses, it’s burdensome to bear the financial and psychological costs of navigating these choppy, uncharted waters without clear direction. And considering the devastating blows to the service industry over the past 18 months, it’s perhaps no surprise that some are in no hurry to take on the added responsibility of enforcing vaccine policies. “I’m not gonna do it. I respect those who are, but I unfortunately don’t have the financial capabilities to be able to do it,” says Nookie Postal, chef-owner of Commonwealth in Cambridge.

Postal says he has felt burned by the failure of the Restaurant Revitalization Fund, a federal program that promised millions of dollars in relief for restaurateurs, but ultimately distributed those monies to just a fraction of the restaurants that applied. Commonwealth has never seen a dime. So perhaps you can forgive him for not wanting to give his staff yet another pandemic-era responsibility, or risk having to turn paying customers away.

“If the federal government wants to replenish the RRF and give us the money we need to survive then I’ll do it gladly. But unless they pay me I’m not doing anything they tell me,” he says. “I’m not gonna be the government’s hall monitor. I’ll do whatever they ask if they pony up, but if they don’t they can fuck off. They told us we were on our own. So we’re on our own.”