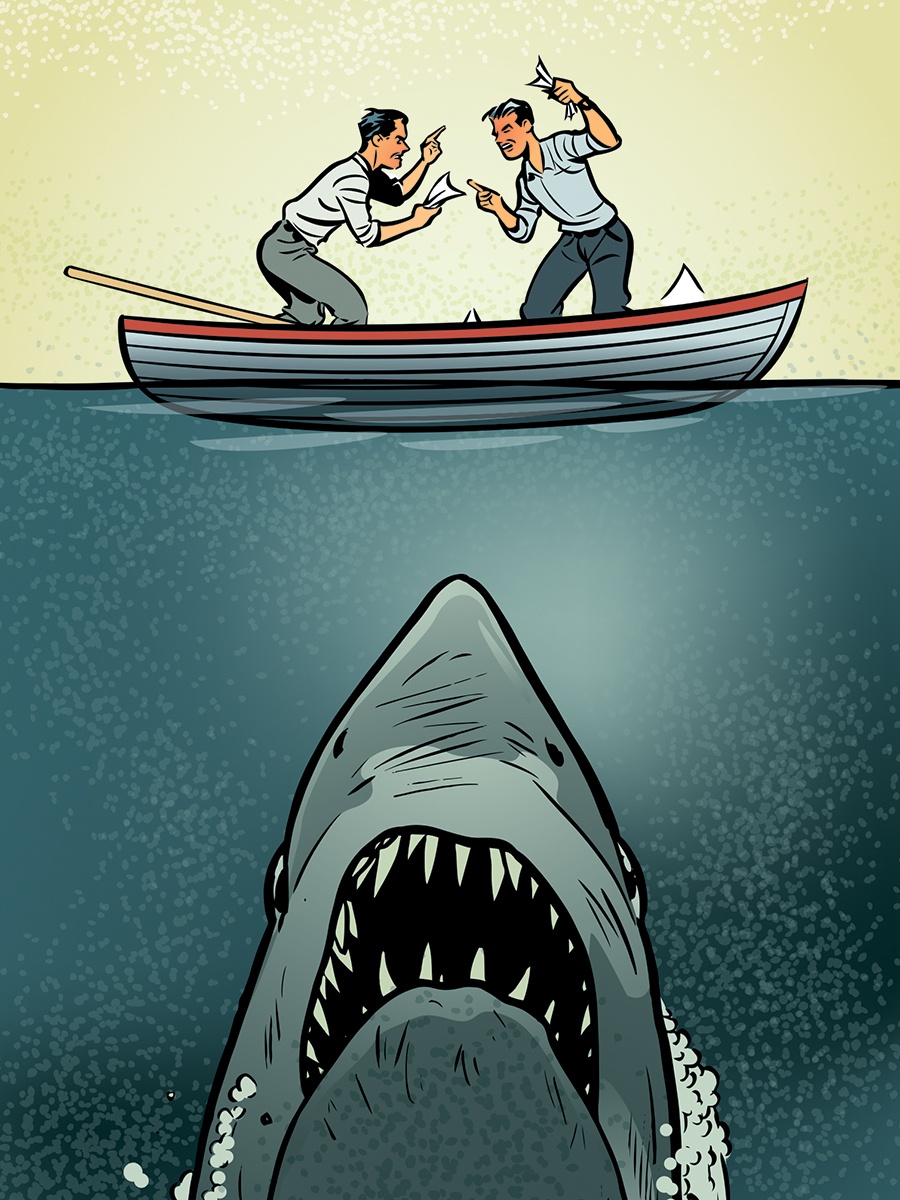

Out for Blood: The Cape’s Biggest Shark Researchers Just Can’t Get Along

Will Cape Cod’s beaches ever be the same?

Illustration by Mark Matcho

Walking down the dock at Long Wharf in August 2020, I was giddy with anticipation. Ulysse Nardin, the Swiss luxury watchmaker, had invited me to tour a 126-foot ship that was docked in Boston before its upcoming voyage. I have minimal interest in fancy timepieces, but couldn’t wait to learn about the boat and its owners and operators, Ocearch, a nonprofit that Ulysse Nardin sponsors. The international research vessel had been tricked out so it could haul white sharks aboard for study before returning them to the sea. I often joke that my spirit animal is a seal, because I can eat my own weight in sushi, could spend the rest of my life on a beach, and have a lifelong, ungodly fascination with white sharks.

After receiving permission to come aboard, I was eager to see all of the ship’s bells and whistles, and I had what I thought were bragging rights: I had written two magazine articles about Greg Skomal, the telegenic shark biologist employed by the Massachusetts Division of Marine Fisheries and the person who gets second billing only to the sharks themselves during Discovery Channel’s “Shark Week.” I had even joined Skomal on a tagging expedition in 2016. Although we didn’t encounter any sharks that day, I was thrilled to be in the presence of a famous researcher who knows as much as anyone about the Outer Cape’s most predatory seasonal residents. Ever since then, I had viewed Skomal as a champion of shark science and one of the animals’ finest ambassadors.

When I boarded the Ocearch vessel that day, Chris Fischer—the plain-spoken founder of the organization and something of a media darling himself—greeted me warmly.

“I think we know some people in common,” I said.

“Oh? Who?” he replied.

“Greg Skomal.”

“He’s a friend of yours?” he asked, his voice suddenly souring. “He’s no friend of mine.”

I was stunned to hear him say that. After all, it would only make sense that Skomal, whose research is funded by the nonprofit Atlantic White Shark Conservancy, and the Ocearch folks were on collegial terms. Apparently I was mistaken.

Fischer went on to accuse Skomal of using his position at the DMF, where he works, to ensure that the agency’s director denied Ocearch’s repeated applications for permits to study white sharks in state waters. In Fischer’s view, Skomal was an egomaniac trying to protect his own scientific fiefdom and his place in the limelight by preventing other researchers from gaining access to the Outer Cape.

His accusations rattled my perception of the shark-research ecosystem. Was it possible that Skomal was the state’s go-to shark expert not because he’s the best, but because he uses his influence at DMF to monopolize the opportunity to conduct research? And what were the ramifications for human safety when top-flight scientists were being blocked from studying sharks at a time when they pose a greater danger to people than ever before? This had all the makings of a David and Goliath story—with potentially deadly consequences. More than a year after that initial conversation with Fischer, though, it still isn’t entirely clear whether Skomal or Fischer is this story’s Goliath.

It wasn’t always this way between Ocearch and Skomal. In fact, Skomal worked as Ocearch’s chief scientist on three expeditions, tagging sharks in Massachusetts and Florida. Prior to 2013, Fischer had no trouble accessing a permit to work in state waters, and in 2014, the Ocearch vessel left for a two-year series of expeditions—to the Galapagos Islands, Chile, Brazil, and Australia—with plans to return to Massachusetts and continue its work in 2016.

That plan was thwarted. In December 2015, before Ocearch had even applied to DMF for a permit for the next summer, the agency’s then-director, David Pierce, contacted Ocearch to say that permission to work on the Outer Cape in 2016 and 2017 would not be granted. According to Robert Hueter, Ocearch’s current chief scientist, despite many attempts to come to an agreement, DMF wouldn’t budge. Ocearch returned to Massachusetts but had to limit its work to federal waters, 3 nautical miles out to sea. (White sharks spend much of their time congregating closer to shore, in proximity to their favorite meal, gray seals.)

Over the next five years, and through this past summer, Ocearch continued to submit permit applications to DMF, only to be rebuffed. The rejection letters offered different (and seemingly contradictory) rationales, Hueter says. On the one hand, in 2016, DMF contended that Ocearch’s methods would drive the sharks out of state waters, compromising Skomal’s population study. Another rejection in 2020 was predicated on the idea that Ocearch’s methods might drive the sharks closer to beaches, endangering the public. “Obviously, both claims can’t be true,” Hueter contends, “and the fact is that neither is.”

For years, DMF has taken issue with Ocearch’s practice of chumming, in which bloody bait is used to lure the sharks. The state alleged that this might affect public safety. The only problem with that? According to Hueter, Ocearch’s most recent application “clearly stated that chumming would not be conducted in state waters.” It didn’t seem to matter. Their application was rejected yet again.

This time the grounds for denial cited Ocearch’s methods, which involve removing sharks from the water. The practice has been forbidden under DMF guidelines since they were put in place around 2015 or 2016, according to current DMF head Daniel McKiernan. Unlike Skomal, who implants his tags onto a shark’s dorsal fin with a harpoon from the pulpit of a fishing boat, Ocearch catches the shark and draws it to the boat’s submerged platform, which then raises the animal out of the water so that the team can collect a variety of data—about body dimensions, blood, bacteria, and parasites—that it couldn’t if the shark were in the water. The shark is also tagged and then released so that Ocearch, and the general public, can soon after begin tracking its movements online.

This practice has both supporters and detractors within the scientific community. Ocearch says it follows protocols established by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee and that they conduct their work in the presence of an experienced, certified aquatic veterinarian to ensure the specimen’s well-being. Fischer also maintains that if his team could work in Massachusetts state waters, they could swab the animals’ notoriously bacteria-infested mouths to help local hospitals and doctors determine which antibiotics should be used to treat people in the case of a non-fatal shark bite. When it comes to animal cruelty, Hueter insists Ocearch’s practices are no more harmful than what Skomal does. “They’re chasing sharks up along the beach and aggravating animals,” he says, adding that this practice is troubling enough for Canadian authorities to have banned it. “There’s video of sharks lunging at Skomal in the pulpit.” What’s more, in the eyes of Ocearch, DMF put the hands-off guideline in place specifically to keep Ocearch out of Skomal’s territory. To the Ocearch team, it’s simply part and parcel of Skomal’s personal grudge against Ocearch.

Ocearch also says that DMF and Skomal extended their persecution of the organization beyond Massachusetts. According to Hueter, in December 2016, Pierce sent a letter to the National Marine Fisheries Service, which manages all federal waters, urging them to limit Ocearch’s ability to conduct research in federal waters. The attempt was not successful, but it escalated the acrimony between Ocearch and DMF. Then, in 2017, a scientist who worked with Skomal sent Canadian maritime authorities an email, to which I had access, that disparaged Ocearch while the group was in the process of applying for a research permit with the agency. Ocearch was eventually given the green light to operate in Nova Scotia. (DMF says the scientist wrote the email without DMF’s permission.)

Hueter denies there is any legitimate reason to blacklist Ocearch or encourage others to do so. He says no other state has ever denied them a research permit, so if their methods are acceptable to everyone else, why not to Massachusetts? “The reality is that DMF’s process for reviewing and granting permits is subjective, arbitrary, and parochial. There is no transparency or external review in the process. Even worse, it creates a blatant conflict of interest,” Hueter says, referring to the fact that Skomal works for the same agency that acts as gatekeeper to the Outer Cape and is able to conduct his own research under its auspices. “Nowhere else, in my more than four decades of shark research, have I seen such a good-old-boy system, designed to throttle competitive, vital scientific research and protect one state researcher’s perceived territory.”

Hueter isn’t the only one concerned that something unsavory is going on. “I really am worried that Greg Skomal is not playing by the normal academic rules, and I would say effectively that there is a conflict of interest,” said another marine biologist, who asked not to be identified by name because he has a relationship with people on both sides of the dispute. “I also think there’s a personality issue, or a human interaction problem. I don’t understand it, but it’s how everyone has characterized dealings with [Skomal] recently. He’s been very defensive.”

Another scientist, Kristian Sexton, who is working with advanced imaging systems to detect sharks using drone technology, also takes issue with the arrangement, in which the same organization is both the group that issues permits and the only one doing research. “I would love to see more scientists conducting research in this area,” he says. “There are actually very few scientific papers coming out of this region.” And therein lies the biggest frustration with Skomal—at least for people on the Cape. Skomal has had exclusive access to the region’s waters for years to conduct a population study that could inform approaches to ensuring public safety, and yet three years after he was supposed to be finished collecting data, he hasn’t released the results, leaving nearly everyone waiting and wondering what should happen next.

It’s clear what the Ocearch team thinks about Skomal and DMF. When it comes to Skomal’s take on Ocearch, though, it’s hard to get an accurate picture, because—in a move that appears wholly uncharacteristic for someone who seems to relish the media spotlight—he declined to be interviewed for this story, passing us off to his boss, DMF director Daniel McKiernan, who eventually did agree to speak to me by phone. He emphasized that Skomal doesn’t have any say in whether an applicant receives a permit to conduct shark research in state waters—even though a letter Pierce, the agency’s then-director, sent to Ocearch on June 30, 2016, indicates he did, in fact, weigh in. McKiernan denies that there is an inherent conflict of interest in having a state agency both oversee permitting and employ scientists conducting research, and says that DMF and the Atlantic White Shark Conservancy, which funds much of Skomal’s work, have an agreement that renders their dealings transparent. However, McKiernan steered clear of attacking Ocearch, barely addressing the organization at all.

A look at some of DMF’s letters to Ocearch and at Skomal’s previous comments to the press, however, make it clear that there is bad blood. In fact, they make it seem as though Fischer is the harasser and Skomal the victim, with DMF doing the right thing to keep Ocearch out of state waters. When DMF first wrote to Ocearch in 2015 to inform the organization that it would not be receiving a permit for 2016 and 2017, the agency explained that it was concerned with how Ocearch’s work could skew the results of Skomal’s ongoing population survey, which was well under way. For one, DMF worried that Ocearch’s tagging methods could scare sharks out of the area. While that might sound desirable for swimmers, any human activity that alters a shark’s normal conduct can jeopardize the research trying to determine the animals’ natural behavior. According to a Scientific American article in 2016, that’s precisely what happened with three of the four sharks Skomal and Fischer tagged together when they were on friendlier terms. Two of the four disappeared from the area’s waters for a year, and one never came back. While no one can say definitively why the sharks left, Skomal and DMF seem to believe it was because they were disturbed by having been lifted out of the water.

In Skomal’s telling, what really seemed to ignite the conflict was when Ocearch—after being denied its permit in 2016—parked itself right at the limit of federal and state waters and dumped chum to attract sharks, altering their natural behavior. At the time, Skomal told the reporter from Scientific American that one of the sharks his team had been monitoring was tagged by Ocearch and subsequently made a beeline out of the area, retreating some 200 nautical miles from where Ocearch had tagged it. DMF feared that the shark wouldn’t return, which would artificially skew the results of the population study. (This may explain why DMF appealed to the National Marine Fisheries Service to restrict Ocearch from operating in federal waters. In fact, DMF wasn’t asking for Ocearch to be banned from federal waters. They were asking for it to remain 10 nautical miles outside of state waters.)

Furthermore, Skomal and DMF are hardly the only ones who have issues with Ocearch. For starters, other scientists agree that it’s unacceptable to invade another scientist’s area of study, and say it’s not uncommon for permits to be denied solely on those grounds.

There are plenty of other complaints about Ocearch, meanwhile, that have nothing to do with Skomal at all: In 2018, Ocearch infuriated people in Canada when its crew began chumming waters close to shore where surfers were present, leading some scientists there to say they didn’t want the group permitted. (Ocearch maintains that they were not chumming near the shore.) A permit for a planned research study in Australia in which Ocearch would be involved was denied. (Fischer blames a protectionist scientist who he says is Australia’s version of Skomal.) Meanwhile, a Facebook page titled “Boycott Ocearch” has railed against the organization, saying that taking sharks out of the water is an inhumane practice that’s less about science and more about getting dramatic photos and sure-to-go-viral video clips, with a sponsor’s name prominently visible in the background, the end game being to attract more funding. (Ocearch denies this.) On the topic of sponsors, critics take issue with the fact that one of Ocearch’s supporters is SeaWorld, which has been accused of reprehensible behavior toward marine mammals. Ocearch has also made room in its limited cargo hold to store barrels of Jefferson’s Ocean Aged at Sea bourbon. In this telling, Ocearch—which has starred on reality TV—is a media-hungry organization more interested in raising its own profile than in conducting pure science or promoting public safety.

Whether Skomal or Ocearch ultimately prevails in this conflict, one thing is certain: The biggest losers will be people on the Cape, who are anxiously awaiting research that promises to inform public safety measures, no matter who it comes from.

Since 2012, one person has been killed in a fatal shark encounter in the state, and there have been five other non-fatal attacks. This summer, once again, swimming was interrupted. Sharks were spotted, beaches closed, and people forced out of the water and into a state of high anxiety.

Anyone who has ever seen a close-up photo of a white shark will have noticed some degree of scarring. Ocean life is a fierce competition, and sometimes two apex predators go after each other, fighting over territory and the rewards of a kill. We seem to be witnessing a similar dynamic between the scientists studying white sharks, while the rest of us are just hoping no one else gets hurt.