Grayer, but Stronger

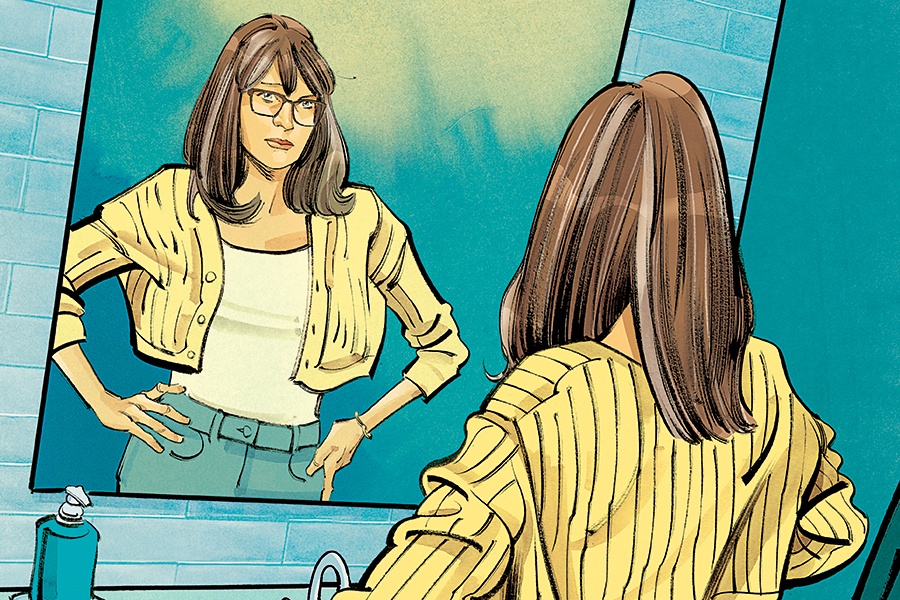

After more than 18 months of pandemic life, how I learned to live with me, myself, and whoever this new person in the mirror is.

Illustration by Kagan McLeod

Recently, I looked through some photos of myself from late 2019, and I couldn’t help but notice that the Lisa in those pictures looked…a lot younger? That couldn’t be possible, I told myself; it was hardly that long ago. I quickly dismissed the idea, chalking the thought up to just another sign I was spending too much time staring at my own face on Zoom. But the next week, when I met up with a friend whom I hadn’t seen much since the start of the pandemic, the person took one look at me and said, “You have a lot more gray in your hair now.”

I think we can all agree that this friend could have led with something slightly more positive after laying eyes on me for the first time in a year. But the truth is it served as the rare occasion when someone was actually just confirming something I had suspected myself: I look different now. And while I’m not that shaken up about my grays (yet), the more I thought about it, the more they felt like a physical manifestation of something I’ve been considering for a while: I’m not the person I was before the pandemic began. Not by a long shot, not even a little.

Of course, this is not necessarily the most surprising epiphany to have right now. It seems nearly impossible to experience what all of us have gone through without being changed in some way. But like many, I had gotten through the early days of the pandemic by promising myself that quarantine was simply a pause in all of our lives, and that we could soon go back to our old ways.

As the months went on, I barely registered the first changes in myself. I didn’t notice when staying home all the time stopped making me feel trapped. Or when I stopped thinking that the minute I got vaxxed, I’d rush to the Paradise, or bask in the blue walls and delicious meze plates of Sarma, or spend quality time gazing upon the always blooming courtyard at the Gardner Museum. I didn’t even notice when staying in touch with loved ones over text instead of scheduling yet another Zoom hangout became preferable. It wasn’t until I sprang out of my cocoon for a post-vax get-together with my oldest, closest friends that I realized I barely recognized the graying, awkward stranger I had become.

I was on the patio at Atwood’s back in June, sharing the plate of nachos that my friends and I had promised one another for over a year, when the new me finally bumped up against my old life. Getting ready that day, I had figured it would be a breeze to ease myself back into my old social life. But as I clumsily tried to figure out how a QR code menu worked, I couldn’t help overthinking everything I was doing. Wait, we weren’t going to watch TV while we ate? And would we be talking about subjects besides the ongoing collapse of society? I suddenly found myself feeling unusually self-conscious. I couldn’t figure out how to make small talk, or fill silences, or even discern when to fill silences.

As I tried to slowly reopen my life, I kept sensing that something was off—and that something was me. It was like trying to put on a shirt I hadn’t worn in a year and a half, and not being able to find the arm holes. Did it fit? I couldn’t tell, because I had just stuck a leg through the collar. This kept happening over the course of the summer, making me think of actor Jude Law in a scene from the early-aughts existential comedy I Heart Huckabees, where he cannot stop repeating the phrase “How am I not myself?” And while I don’t think I’m a villain the way his character was (I’m not named Brad, and I don’t look like Jude Law), there’s something about his plaintive question, and the way he asks it over and over again, that has stuck with me throughout these many months. If I’m not the me I once was, then how, exactly, am I not myself?

Sometimes I felt like I was in one of those movies where an adult body-swaps with their younger self, and I was trying to experience a life I’d left behind. I still wanted to go out to dinner with friends and see movies, but I wanted to return home earlier. Or I’d weigh the lure of a new library book against going out, and really have to work on talking myself into leaving my apartment. When I did venture outside, my friends and I would inevitably end up having the Sadness Talk. We’d run through dating/family/workplace drama, and then check in about how sad we’d been at various points in the previous year, how sad we were currently, and how differently we felt about things in our lives, having been that sad.

This was, perhaps, the most notable part of the New Me. For more than a year, I’d wake up and my heart would break. And then I’d wake up the next day, and my heart would break again. Sometimes it shattered for the same reason days in a row, and then other, awful things would happen, and I couldn’t look away, and it would fall apart again. After a while, that heartbreak settled into my face, into my bones, into what felt like my actual cells.

A raggedier, more cynical version of me was trying to fit into the shape of my old life, and it took some getting used to. It wasn’t exactly that I had turned into that person who obnoxiously replies “and you’re surprised?” any time someone expresses shock at some tragic current event. But there’s a certain utility in being forced to give up magical thinking. Over time, it shifted the tenor of my conversations with friends to somewhere darker, but ultimately truer.

Some of these feelings, I realize, are a natural consequence of aging—the downsides of which, so far, have included parts of my body not working properly anymore, getting tired more easily, and neither recognizing young celebrities nor the reason they are allegedly famous. Usually, though, you get a decade or more to acclimate to that new reality. For me, it felt like the transition from thirtysomething to middle age took place over a short 18 months. In the blink of an eye, I went from deluding myself that I could still occasionally feel like a part of the Zeitgeist to accepting that the whole point of the Zeitgeist is most often to make you feel how far away from it you are.

Still, there is an upside to getting older. Ideally, you’re encountering the world with slightly more grace than you had before. I feel quieter, calmer, and more rooted in the place I live. I had already mostly gotten over my fantasy of living abroad, but for the first time in my adult life, I can say the reason I won’t be moving abroad isn’t because I simply lack the will to do it. It’s because during the pandemic, my roots in the Boston area have started to feel much deeper, as though they, too, aged at warp speed. Since February 2020, I have watched my nephew—who was part of my bubble—go from not even crawling to running and trying to say my name (we’re at Cece, but that counts). I can’t even fathom missing the moments when he learns to ride a bike, make sarcastic jokes, or argue about whether bagels are better toasted or not. I went through 18 months of not being able to be in the same room as my longtime best friend, and now he lives in the apartment beneath me. How could I leave any of this?

This new sense of self does not mean that I have stopped tripping over all of the anxieties I bring upon myself. I’m still as neurotic as ever (occasionally, I imagine reaching a very old age and then being worried I’m dying in a way that inconveniences a hospice nurse). I still procrastinate on every single task that would make my life run more smoothly—and then feel badly about it. A short list of things I continue to avoid includes conflict, tough decisions, and regular exercise. Despite this, somehow, I feel better equipped to face the abundant challenges confronting the world in 2021. I may have felt lighter before all of this, but feeling heavier, in my experience, also means I feel a lot more grounded.

In fact, from where I sit it seems the pandemic has brought out all of our true selves, as though the strife and challenges stripped off a layer of veneer. If you were a person who was an ass to servers or flight attendants, you’ve graduated to being the person who appears in viral restaurant or in-flight horror stories. If you were the person who always had a minute to help a friend, you probably launched a mutual aid fund. I haven’t started writing unhinged Yelp reviews or shown up on any Nobel Peace Prize nominee lists, but I do think I’ve always had a capacity for empathy and a patience for coping with darker human emotions, and these qualities have increased exponentially during this time. My sadness may have settled into grief as time has passed, but my ability to accept it could certainly be called growth.

At the end of the day, gray is just a color, and someday not so long from now, I’ll realize I look different again, and have to accept it. Regardless of what global events are going on, life is always going to be one long series of looking in the mirror and thinking, When did I start looking like that? For me, and I hope for anyone else peering in the mirror after an awful year and a half that left many looking a bit more haggard, a little heavier, and a lot shaggier, the question is less about how that person looks and more about who that person is. In my case, that person may not be what I expected, but she’s exactly who I need right now.