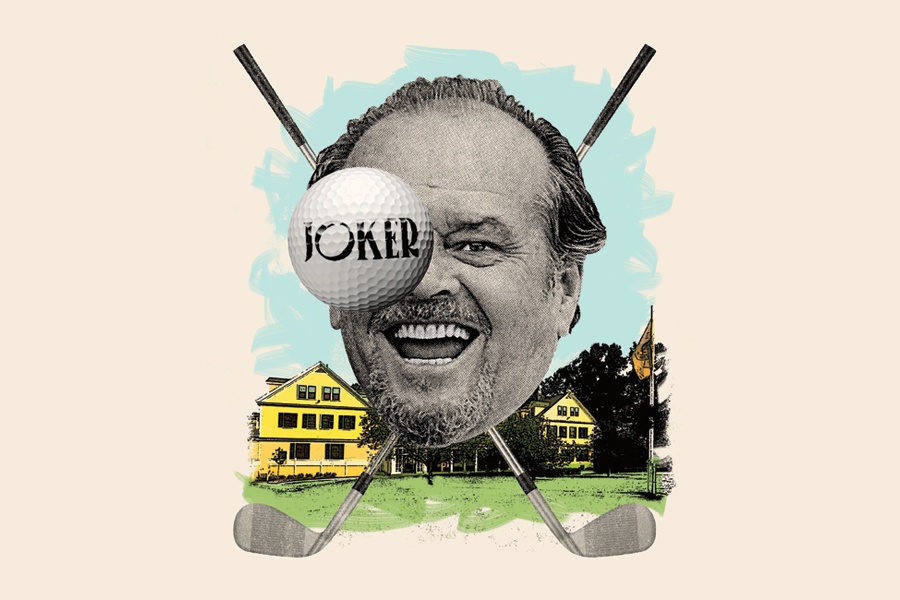

My Round with Jack Nicholson at Brookline’s Country Club

Following a 34-year hiatus, the U.S. Open Championship is once again coming to The Country Club in Brookline this month. But nothing will ever compare to my afternoon on those hallowed links with Jack Nicholson.

Illustration by Benjamen Purvis / Getty Images

There are few things in life I remember as vividly as the day Jack Nicholson took his shirt off in the middle of a golf game with me at The Country Club in Brookline. It was a scorching-hot day in the early aughts, and he had completely sweated through his polo after three holes. So he stripped it off, went into a golf bag that seemed to have 50 pockets, pulled out a fresh shirt, and put it on.

“No one has ever been naked from the waist up on the third hole of The Country Club,” remarked my buddy Billy, a member whom I’d brought along for tips on reading the course, particularly the greens.

Undeterred, Jack smiled his wicked smile. “I’m a groundbreaker,” he said.

I had first met Nicholson many years earlier at his house in 1979, not long after he won the Academy Award for One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest. My wife and I were taken there by our producer friend Harry Gittes, who had gone to Brookline High School. From the hills of Mulholland Drive, Nicholson’s house overlooked the sprawl of L.A. Every blinking light you gazed upon held the promise of stardom—the fool’s gold of Hollywood. Tuborg from the bottle was the drink of choice that night, the kitchen fridge loaded with green bottles. Nicholson was clad in a white suit, with white lace-up shoes and no socks. He spoke in a kind of jazzy Esperanto, offering commentary that seemed a combination of inside jokes and Bartlett’s Familiar Quotations. Totally original. My wife and I, trying to say clever things, felt increasingly out of it, surrounded by Nicholson and part of his posse, including Anjelica Huston and the character actor Harry Dean Stanton. A lot of the conversation centered on earthquake predictions from various L.A. psychics, and where they all would flee to escape the chaos, which they thought was going to happen that weekend.

Leaving Nicholson’s house in the back seat of Gittes’s classic Volkswagen bug convertible, the producer told us, “Jack and I are friends because we appreciate, more than most, the absurdities of life. He and I talk a lot about what we call ‘the dream of the three cherries.’ Hitting the jackpot on the slot machines. That’s what Hollywood has always held out there, for the believers: the dream of the three cherries.”

Jack and I caught up again while he was filming The Departed in Boston in 2005, when I invited him for a day of golfing at The Country Club. He brought his friend Tommy, who seemed like someone who only trusted you if you grew up in New Jersey. I invited Billy, who grew up in Somerville and was street-smart, like Nicholson. Excited to be playing with Hollywood royalty, Billy had two personalized golf hats made up with the club logo, one that read “Tommy” and the other “J.J. Gittes”—Jack’s character in Chinatown.

Tommy didn’t seem to be very prepared. “I can rent some shoes…right?”

Billy pointed out that TCC did not rent shoes. “What size are you, Tommy?”

“Eleven.”

Billy disappeared and came back almost 20 minutes later with a pair of golf saddle shoes, black and white. “Try them on,” he instructed, handing them to Tommy. Then he said to me, “I jimmied open a dozen lockers. Found a size 12; oughta work.”

That’s why I brought Billy along—for the street smarts. He could probably start a car with a screwdriver.

The Country Club is a walking club, the way golf should be played. It was frowned upon to ride in a cart. For many years, if you wanted to take a cart as a member, you had to present a letter from a doctor attesting to your disability. “This is a club for sportsmen,” Gerry Church, a two-term president of the club and a purist about the rules of golf, told me years ago. “The players are meant to enjoy the surroundings of nature. It’s a walking sport.”

Nicholson, however, didn’t care much for club rules. “I’ve got to take a cart,” he insisted. “I’m wearing long pants in the summer. My club at home, Bel-Air, is the only one in L.A. that demands men wear long pants, even if it’s 105.”

The weather wasn’t much cooler here. The morning of our match, it was already almost 100 humid degrees when I got a phone call from Team Jack (every Hollywood star has a team, a posse, an entourage). “Jack says it’s way too hot—got to cancel.”

“Tell him we’re playing later in the day,” I said, “and he can’t pass up a visit to this Valhalla of golf.” So he came.

Over the years, I’ve thought of this day many times as I headed out for an afternoon hitting the little white ball. And this month, it’ll be top of mind again as the U.S. Open Championship comes to The Country Club—the site of my famed match with Jack—on June 16 for the first time since 1988.

There’s an old saying: Golf is the only thing you’ll ever do in life where you get what you deserve. The pro golfer Jimmy Demaret, meanwhile, has said that “Golf and sex are about the only things you can enjoy without being good at.” There are probably more jokes about golf than about any other sport in history. It’s an addictive game that many people at various stages of their golf life swear they’re going to give up. They throw clubs into ponds or over fences. They snap their clubs in half. But they just can’t quit. I believe that you can tell a lot about people’s character if you play golf with them. It exposes bad behavior: how they treat the caddies, if they curse bad shots, if they cheat. If they tell raunchy jokes.

Serious golfers have their bucket list of famous courses they have to play. Perhaps at the top of these lists is Augusta National, home of the Masters Tournament. Close to that peak is The Country Club in Brookline, for many the cradle of golf in America, hallowed ground. Founded in 1882, it was originally a retreat for the Yankees of Boston, a place for horseback riding and racing on a circular track in front of the clubhouse. In 1894, it became one of the original five clubs that established the U.S. Golf Association.

The deep history of The Country Club has invited prestige for years. But inviting the famous was never universally welcomed. “This club is supposed to be a refuge for your friends, classmates, and true sports enthusiasts,” a longtime member said to me years ago. “Not watchers of sports, but active players.”

We are an aspirational nation. If there is something out there that’s difficult to attain, we want in. Like shooting a round at The Country Club. It’s a dream for many golfers to play there.

Which brings me back to that hot summer day with Jack. Unloading the gear, my eyes wandered to his clubs, swaddled in animal-print head covers in a golf bag that looked like it belonged to a giant. “That’s the biggest bag I’ve ever seen,” I remarked.

Nicholson winked at me. “Be prepared for anything, Johnny Boy.”

On the first tee, Nicholson looked at me and said, “Johnny Boy, just to let you know, I don’t take more than a five on any hole.”

“Fine with me,” I answered. Then he proceeded to wail the ball with his driver, knocking it at least 220 yards down the middle. If he didn’t like a shot, he’d drop a few balls (all of them had “Joker” stamped on them), and hit those as well—all with authority.

He was good. We played from the white tees, forward from the back markers. Most weekend golfers play from the white tees.

“Did you play when you were a kid?” I asked him.

“You don’t play golf until you figure out other things,” he told me. “When I looked around eventually, it seemed a lot of people I liked were playing the sport, and thought it was really a hard game. Right up my alley. But I took lessons first for a long time before I ever played an actual hole on an actual course. It was all preparation. It’s also how I approach a new part in a movie. Immersed in it. That’s my approach to acting. It’s how I approach anything new.”

The temperature kept rising. “I’m dyin’ out here, Johnny Boy,” Nicholson said. And he was riding with Tommy. Billy and I were walking, the heat boiling up through our shoes. I was not happy either.

At one point, Tommy hit his ball into the woods. I was on the fairway. Nicholson swung the cart around. “Hop in, Johnny Boy.”

“Thanks. It’s only 50 yards to the green,” I said.

“Whoever can make your life easier, 50 yards, a thousand miles…accept it.”

Later in the round I said to him, “Boston is such a prickly, different place—you’re probably bugged here less than anywhere else. In this town, we pretend to never suck up to celebrity.”

“Au contraire,” he said. “Just last night, Tommy and I were out to dinner on the waterfront with a couple of old girlfriends, and a woman comes over. She leans down and says, ‘Hey Jack, how’d you like to take me into the ladies’ room and spank me?’”

“‘Not tonight, sweetheart,’ I said to her. ‘But Tommy probably likes to do that…and I can watch.’”

He wanted to quit after nine holes—it was just too oppressive in the heat. “You can’t stop now, Jack,” I said. “At least you have to play #11. It’s a par 5, called the Himalayas. The names of the holes have been around for decades. You’ll see on the tee at #11, the Himalayas look to be 1,000 yards long with a steep hill leading up to the green. It’s actually 513 yards. I’ve never parred the hole in the many times I’ve played it. Why don’t we just play 10, 11, 12, and then go in?”

Nicholson nodded.

“Any women’s names for the holes?” he asked.

“Well, we have Pond, Paddock, Liverpool, Elbow. Oh yeah, #10 is called Maiden.”

Nicholson parred the Maiden and the par-5 Himalayas, and bogeyed the short downhill par 3, #12.

Billy and I dragged our sorry bones toward the clubhouse while Nicholson and Tommy whizzed away in their cart to wait for us by the pro shop. “I’ve paid the caddies,” Nicholson said to me when we got there.

“You didn’t have to do that,” I replied. “What about the old line in Hollywood, ‘The talent never pays?’” He flashed that killer grin at me. “Right,” he said, then paused. “But it’s okay,” he added, hesitating. “I’m rich!” We went into the locker room, where there was a handsome bar but no air conditioning, and ordered beers and nibbled peanuts. We talked about the history of the club, past U.S. Opens, Francis Ouimet’s win in 1913, and that incredible victory of the U.S. in the 1999 Ryder Cup—particularly the end of the match, when Justin Leonard sank the long putt on the 17th hole and the celebration began.

“I know Michael Jordan was there,” Nicholson said.

“Yup,” I said. “He rented a house nearby and people couldn’t believe he was here, just wandering like everyone else, hole to hole, one of the guys, being the fan.”

We talked a while about collecting art, and how much he admired the famous collection amassed by one of Hollywood’s great bad guys, the actor Edward G. Robinson. “He was disciplined,” Nicholson said. “The great ones are disciplined. Anything that looks easy is only easy from the outside. Even three-foot putts. Not easy.”

We left the bar and walked up a small hill to where the white stretch limo was waiting.

Boston is a city, I’ve said before, that pretends to be disdainful of the famous. One dowager from Beacon Hill once told me at a dinner long ago, “Celebrity is so common,” meaning not in a good way. I had told no one about playing with Nicholson before the event, but word had spread quickly. There were about 150 people surrounding the limo, many in bathing suits, folks who had come over from the club’s swimming pool next to where the car waited.

“We love you, Jack,” people yelled. He had already made his way into the back seat. But out he came. He handed me one of his golf balls, stamped with Joker. Then he did a little dance, like a hornpipe, for the crowd. They went nuts. Jack hopped back in, and the limo rolled down the drive as the people continued to clap, cheer, and whistle. The limo driver beeped the horn twice.

The Joker was wild.