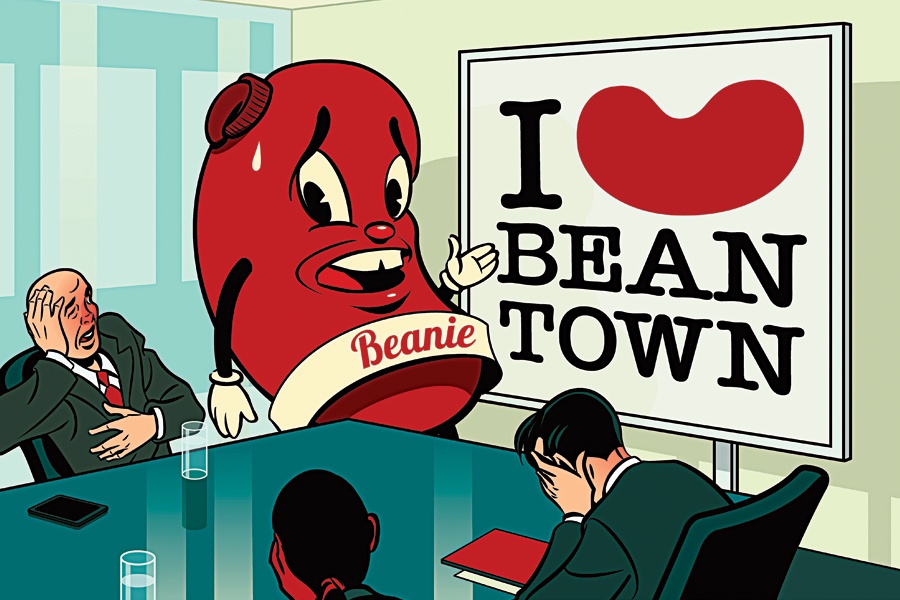

Why the Name “Beantown” Has to Go

There are hardly any restaurants in Boston still serving traditional baked beans—so why on Earth are we still calling ourselves “Beantown”? It’s finally time to shelve the city’s canned nickname for good.

Illustration by Mark Matcho

As a proud Bostonian who cares deeply about our city’s future and its reputation, I’ve given a lot of thought to the moniker “Beantown.” When, for instance, was the last time you heard a parent, an uncle, an aunt, a cousin, a sister, a friend, or even a neighbor refer to Boston as “Beantown”? Never, that’s when. And I’m willing to bet that most of them don’t even know the origins of the appellation. At best, it’s a nickname made for tourists—and even with them, I’m not so sure it has much traction.

To prove the point, I went to the aquarium one recent Saturday to ask some tourists if they’d ever heard of “Beantown.” Rhona Bergin, who was visiting from Ireland with her partner, Colm Byrne, sure hadn’t. In fact, Bergin told me she’d recently posted a picture of Boston on Instagram and was perplexed when a relative commented, “I love Beantown!”

“What’s ‘Beantown’?” she asked.

“I thought it was what they called Chicago,” Byrne said.

Who could blame him? Boston has been out-beaned by Chicago’s Millennium Park, where “The Bean”—a scintillating silver sculpture designed by Anish Kapoor—draws nearly 13 million visitors each year. That’s also what 26-year-old Katie Kracht, visiting from Wisconsin, told me: She thought “Beantown” should refer to Chicago.

In case I was missing any tourists driven here in search of beans, I asked Jim Healy, who has been in the hospitality business working at Boston Duck Tours since it opened 28 years ago, if he could recall any who specifically asked for a good place to find Boston baked beans. He paused until he remembered just one, saying he sent the out-of-towner to Durgin-Park (which no longer exists). Perhaps the most preposterous thing about calling Boston “Beantown” is the fact that it’s not an easy place to find Boston baked beans. Some of our oldest, most classic restaurants are disappearing, and with them, the iconic dish. It is rumored that the former Durgin-Park, a classic tourist spot for nearly 200 years that sat in the middle of Faneuil Hall Marketplace, may next become a cannabis dispensary. And so it goes.

Which brings us to today: We’re a town with a moniker that is meaningless to most residents, unknown to many tourists, and refers to a dish that is increasingly tough to find. I’m drawing a line in the brown sugar and saying that it’s time to do away with “Beantown” and come up with something that better reflects who we are. Because, in addition to all the other reasons, how can we possibly continue to allow the birthplace of the American Revolution, the home of world-class higher education, and the fertile ground of medical and technological breakthroughs to be reduced to a legume stewed in molasses, cooked in pork fat, and best known for producing flatulence? In short: We simply cannot.

We’re a town with a moniker that is meaningless to most residents, unknown to many tourists, and refers to a dish that is increasingly tough to find.

Before deciding whether to jettison our nickname for good, it’s important to understand something that many Bostonians don’t—how “Beantown” was born in the first place. In the beginning, baked beans were a staple of Native Americans, originally prepared with maple syrup and bear lard. New Englanders later modified the recipe to include pork and brown sugar—and also molasses, which John Adams called “an essential ingredient in American independence” because it wasn’t subject to British taxes. (Not noted by Adams: the fact that molasses was an integral ingredient in perpetuating the slave trade.) Puritans, who faithfully observed the Sabbath by not working or cooking on Sundays, prepared giant crocks of baked beans on Saturday, which were kept warm in their hearth throughout the weekend. Soon enough, visitors started referring to Boston as “Beantown.”

It might have died there but for the tinkering of an ambitious politician. John F. Fitzgerald, the 39th and 41st mayor of Boston as well as the grandfather of President John F. Kennedy, decided to make baked beans the starring character in Boston’s latest advertising campaign. It was based on “Old Home Week,” an economic improvement strategy and event that originated in New Hampshire designed to lure tourists—often former residents who had moved away—to the region to spend their money. In 1907, mayor “Honey Fitz,” as Fitzgerald was called, brought the concept to Boston. “It will be a splendid opportunity to stimulate public sentiment here and to advertise to the world the progress that Boston has been making and the great opportunities that she possesses along industrial and commercial lines,” he announced.

The city mailed one million stickers across the country to advertise the special event, all bearing the indelible mark of a baked-bean pot. If that wasn’t enough, event organizers insisted that the week would feature a “Boston Baked Bean” day to celebrate the staple’s strong association with the city. “Beantown” was officially born, with its very own debutante party to boot.

The references continued throughout the early 1900s and beyond. Boston’s National League baseball team was dubbed the Beaneaters, and in time, a popular slogan began appearing on postcards: “You Don’t Know Beans Until You Come to Boston.” In the 1950s, organizers put together a little regional collegiate hockey tournament called the Beanpot, which has become a huge event and still continues today. In the 1980s, CBS aired a television sitcom about a fictional news show called Goodnight Beantown. The series lasted only two seasons, but Boston’s nickname nevertheless persisted. And at least for a while, so did the side dish on the menus of local restaurants. Today, though, Union Oyster House is one of last remaining spots that serves it. “People come here for the history of the restaurant,” said Rico DiFronzo, the eatery’s executive chef. “In some ways, they expect to see baked beans, fish chowder, that classic New England food. I guess if you go to Philly, you’re looking for a steak and cheese.” He has a fair point—but I have a better one: Philadelphians know better than to call themselves “Cheesesteak-town.” And we should, too.

If you’re looking for evidence that a well-thought-out slogan can be of huge benefit to a city, look no further than Las Vegas. No city promotion has ever been better received than that of Sin City. Adopting the slogan “What Happens Here, Stays Here” in 2003 literally changed the fate of the place in nearly every way: culturally, economically, and historically. The campaign took years to develop and cost tens of millions of dollars to implement, but the Las Vegas Convention and Visitors Authority has said that its effect “defied expectations by any standard.”

Any government official pondering our city’s tourism future, meanwhile, will most likely notice the familiar fault lines of Old Boston versus New. It’s everywhere you look: our politics, our economics, and, yes, even our food. Many of today’s politicians and business owners hope to move toward a point where we talk about the gleam of Boston’s future rather than the nostalgia of its past. Even the gas street lamps of Beacon Hill are making way for environmentally sound LEDs. And there is no denying that baked beans sit comfortably in the Old Boston category. The question is, what is the LED equivalent of “Beantown”?

Figuring that out will require something of pure magic. Reaching the success of Vegas’s mega-hit campaign, or the iconic “I Love New York” slogan, requires a strategy far grander and more modern than anything Honey Fitz ever cooked up. Plus, the risks of getting it wrong are not to be underestimated. As Brandingmag warned, rebranding strategies can “often run the risk of causing more problems than you solve,” such as alienating an already loyal base. No one learned this lesson better than the state of Rhode Island. When it rolled out its confusing catch phrase “Cooler & Warmer” in 2016, locals mocked it mercilessly for, well, making no sense. And that was before it became public that the campaign—which cost $3 million—included a commercial that featured a shot filmed in Iceland. Apologies were made, the campaign was quickly canceled—and so was the state marketing official responsible for the effort.

After much consideration, here is my advice to the Greater Boston Convention & Visitors Bureau: Find us a new slogan, please. And when you do, make sure to go for the home run—the grand slam even. Take a page from those who really did it right and spend the time, the money, and the energy to discover who we are, what makes us great, and how we can say that in just a few catchy words. If done right, we won’t regret saying, “Goodbye to Beantown.”