The New Race to Rule the Automile

For decades, the likes of Herb Chambers and Ernie Boch transcended Boston's multibillion-dollar auto industry by making their way into local lore as household names and cultural icons. Now, with the advent of disruptors like Tesla and Carvana, is the era of the car titan coming to an end, or will a new generation of mega-dealers find a way to keep their foot on the gas?

Chris Chase was excited. Early last year, the Boston construction manager spied an email in his inbox from someone at Herb Chambers Ford of Braintree regarding the new truck he was hoping to buy. It wasn’t just any truck, but the vehicular version of an all-the-fun-and-none-of-the-guilt diet, the truck that took the all-American pickup and propelled it into a carbon-neutral future. It was the all-new, all-electric Ford F-150 Lightning.

The truck was the most hotly anticipated car release in recent history, and Ford had a new system in place to handle purchases: Customers would reserve their vehicle with Ford directly and then choose a dealership where they would purchase it once it was ready. Chase was among the 200,000 people across the country who reserved one before Ford, overwhelmed with reservations, stopped taking them altogether. He chose the Chambers outfit in Braintree because of the shop’s excellent reputation.

When Chase opened the email, though, he suddenly felt a lot less enthusiastic. “As a dealership, we are going to be selling these vehicles over MSRP,” it read, referring to the manufacturer’s suggested retail price. “I have had a meeting with my general manager, and the price point has been set at $10,000 over MSRP. This will be locked in across all trim lines for both the 2022 & 2023 model years.” Chase considered canceling his reservation.

High demand and higher prices for cars are, of course, nothing new. Ever since the pandemic caused supply-chain issues and microchip shortages, car inventories across the country have shrunk, and many dealerships have subsequently jacked up prices for consumers desperate to get their hands on a new car. The overwhelming demand for the Lightning, though, put that trend on steroids, angering legions of consumers across the country who received similar letters from dealers who had also decided to tack on pricey markups—one as much as $30,000 to get the truck sooner—and ask customers for additional deposits.

United in their outrage, truck buyers took to the Internet to share their thoughts. On one Ford F-150 forum, a user said he couldn’t wait for the day that manufacturers tore a page from the Tesla playbook and sold directly to consumers—cutting dealers out of the equation entirely. The social-media firestorm paid off when Ford took notice of the anger—some of it directed not at dealers but at the manufacturer itself—and told dealers that any shady sales practices, requests for extra deposits, or misleading advertising would result in the dealership not getting any Lightnings from the factory. Ford didn’t forbid markups, but even still, Herb Chambers Ford of Braintree walked back its initial price hike and pledged that the dealership would honor the manufacturer’s suggested retail price after all. Sadly, Chase didn’t have the opportunity to get his truck at the MSRP price. He died in April.

In September, Ford kicked it up another notch: The company announced that only dealers willing to make significant investments in electric-car infrastructure and sell electric vehicles at fixed, no-haggle prices would be among the dealers allowed to sell Ford’s in-demand EVs. At press time, local dealerships were still deciding whether to go electric or bow out.

The dustup over the electric F-150 and the policy Ford has put into place is just one sign of the dramatic changes on the horizon for car dealerships in Massachusetts. On almost every front—political, economic, and technological—major disruptions to the car-selling business are coming down the literal and figurative pike. As we move toward an electric-only future, with more direct-to-consumer purchasing options for new cars (Tesla, Rivian, and Lucid) and the rise of online used-car retailers (Carvana, for one), the traditional model of the locally based car dealership faces unprecedented challenges. This raises a question: Are the kings of the Automile—the men like Ernie Boch Sr. and Herb Chambers who made their fortunes selling cars—the last of their breed, or can the next in line somehow find a way to speed into a new era of car buying in Boston?

Ford unveils their new electric F-150 Lightning outside of their headquarters in Dearborn, Michigan on May 19, 2021. / Photo by Jeff Kowalsky/Getty Images

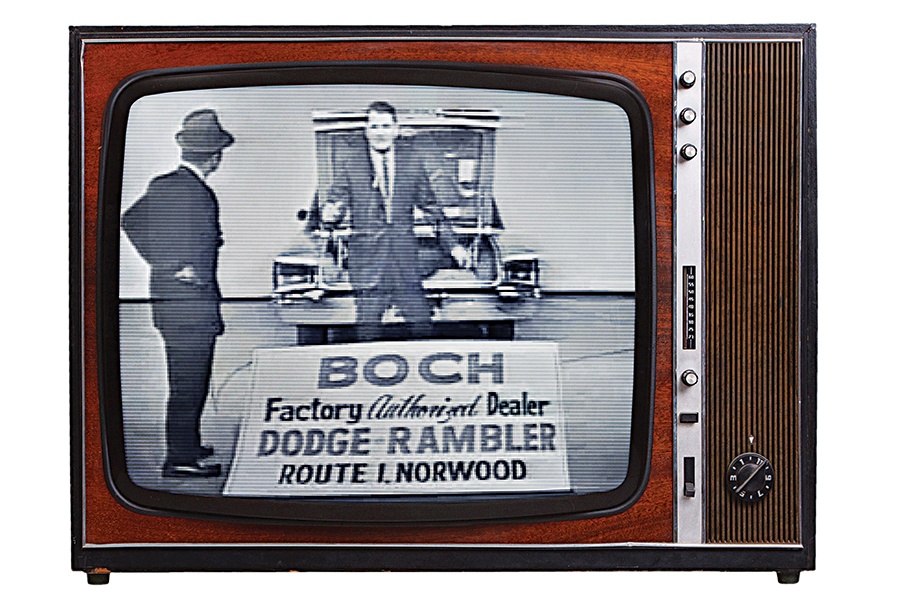

There was a time, not so long ago, when the local car dealer was also a local celebrity. One black-and-white television ad from the 1960s opens with a hammer coming down on a brand-new car’s window, smashing it into tiny pieces of glass. Then Ernie Boch Sr. appears, telling viewers, “Nobody smashes stickah prices on new 1966 Dodges, Ramblers, or used cahs like Boch,” as he bobs forward slightly every few words for added emphasis. In another commercial, he jumps out of a car trunk to announce, “I challenge, yes challenge, any dealer, anywhere, to match our stickah-smashing price deals.” Even if he didn’t look particularly comfortable on camera, his signature tagline, “Come on down,” accompanied by a stiff-shouldered sweep of his arm, created an oddly comforting sense of familiarity in Boston for decades.

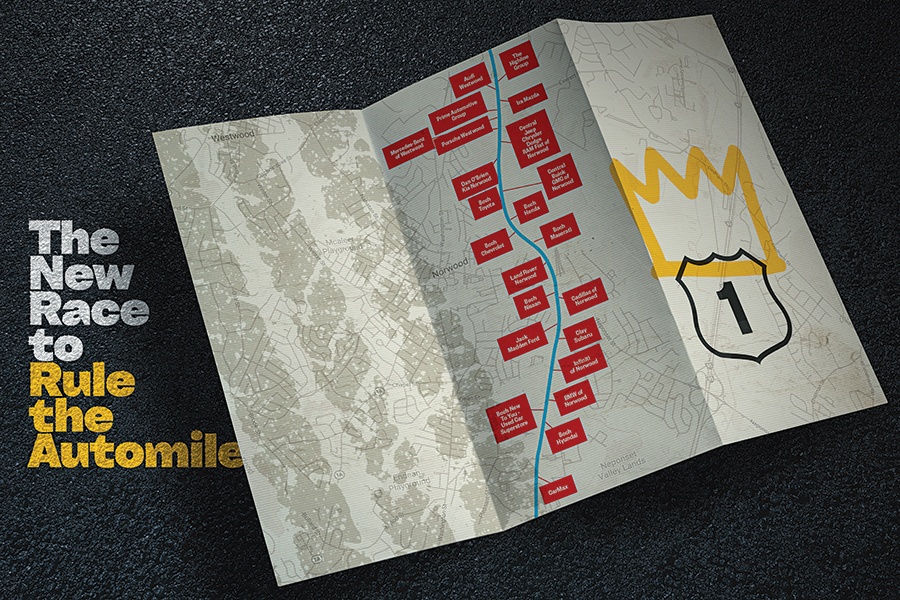

Boch Sr.’s success didn’t just come from making memorable TV ads. Inheriting a lone gas station and a single car dealership from his father, he managed to turn them into a gold mine—an automotive empire spanning multiple car brands along a stretch of Route 1 in Norwood that he dubbed the Automile. Nothing, though, proved more prescient than his purchase of Subaru’s New England dealerships before anyone could have imagined that a little-known Japanese brand would go on to become the quintessential New England car and make the man who made it all happen fabulously wealthy.

Boch Sr. soon became the owner of radio stations and moved to Martha’s Vineyard. He also built a monstrosity of a home with gold-plated shower fixtures and installed a small herd of llamas on the lawn. In other words, even when he wasn’t selling cars, he made himself tough to ignore.

A couple of decades after Boch’s TV ads made him a local celebrity, another titan of the Automile, direct competitor Herb Chambers, began making himself known on the strength of his rags to riches story—now the stuff of local lore. Chambers was a kid from Dorchester, a high school dropout, who started out as a copy-machine repair man. With a quieter personality yet no lack of presence, he built his own wildly successful copy-machine company and then used the millions he made on the sale to enter the car business. Today, he is not just a billionaire but by far the biggest Massachusetts-based car dealer.

Chambers, though, is known as much for selling cars as for his charity work and public image: a man in finely tailored suits who favors the silk pocket square, stepping out of his helicopter. It is the chopper he uses to commute from his stately Connecticut River–side home in the Constitution State to work at his Mercedes-Benz dealership in Somerville. Meanwhile, Ernie Boch Jr., who inherited his father’s dealerships, also became famous—less for expanding his business and more for his eccentricity and unfiltered mouth. As a young man, he starred in his own quirky TV car ads and became a fixture on shock-jock radio shows. He’s also become a leading philanthropist in his own right.

For these kings of the Automile, name and face recognition weren’t just the byproduct of success—they were also its motor. That’s because business on the Automile has long been an ecosystem of head-to-head, personality-based competition. “My name recognition was purposely done to build business. There was a big commitment to it and a wanting-to-win strategy,” says Boch Jr., who in recent years has sold off much of his empire, retaining only his Ferrari and Maserati dealerships, as well as the Subaru distributor built by his father.

Not all car dealers are as recognizable as Chambers and Boch, but as a group, they are a formidable force. “We have a substantial economic footprint in the Massachusetts economy,” says Robert O’Koniewski, executive vice president for the Massachusetts State Automobile Dealers Association (MSADA). “We are 20 percent of the retail economy in Massachusetts, so one out of five retail dollars goes to a dealership and a franchise dealership.”

That kind of impact—not to mention frequent campaign contributions to

politicians—has also made auto dealers a political force in the state. Over the years, individual dealers contributed to Governor Charlie Baker’s campaigns. Meanwhile, Baker has gone to bat for the auto industry and its interests. He made an ultimately unsuccessful bid to exempt car dealers from paying their commission-based salespeople overtime and premium pay. During the pandemic, he also prioritized car dealerships in his reopening rollout over other nonessential industries. He has been a regular speaker at MSADA’s annual meeting.

Still, nothing in recent history has lifted the industry more than the pandemic-era car shortage and the resulting sky-high markups. There was so much money to be made that dealers took to buying cars back from customers for more than they had originally sold them, only to turn around and sell those same cars at a profit to new customers. While some smaller dealerships suffered due to painfully low inventory—and the industry suffered a new low in its reputation—for the most part, car dealers made a killing, breaking profit records. But now, as that moment appears to be coming to an end and the winds of change once again begin to blow, it may well be remembered not merely as a temporary boomtime but rather as the auto dealers’ last hurrah.

Photo via Zim286/Getty Images

Most people don’t know who he is, but Chris Dagesse now owns the second-biggest locally based dealership group in the state. / Photo by Christopher Churchill

No matter where you look these days, there are signs that the times are changing for auto dealers. Shifts in the kinds of cars being made and how they are sold pose nothing less than an existential threat to the entire enterprise of automotive dealerships as we know them today.

For starters, the move away from fossil-fuel-powered cars promises to be an electric shock to the dealer system. In August, Massachusetts passed a climate change law that bans the sale of any new fossil-fuel-using cars by 2035. That may sound like a long way off, but change happens faster than you might think. This past summer, the United States hit an important threshold: Five percent of new cars sold were fully electric. It may not sound like a lot, but according to a Bloomberg analysis, if the country follows the path of 18 countries that adopted electric vehicles sooner, a quarter of cars in America could be electric in just three more years.

That could make a big dent in dealers’ bottom lines—and fast. That’s because under the current business model, the service and repair of cars, with things like oil changes and transmission fixes, account for a significant portion of a dealership’s revenue. Electric cars don’t need oil changes, and most often their transmissions have only a single gear.

Meanwhile, selling electric vehicles is going to be expensive for car dealers. Ford’s demand that they invest a minimum of half a million dollars in electric infrastructure if they want to sell their in-demand electric vehicles is a major hill to climb—and an insurmountable one for some smaller outfits. Still, Ford is offering a more flexible deal than other U.S. car manufacturers; after all, dealers can still opt to sell only Ford’s internal combustion engine models. Buick, on the other hand, announced in September that any dealer unwilling to invest a couple hundred thousand dollars in electric-car infrastructure and training would be offered a buyout. (Translation: Either get onboard or get out.) Cadillac, also a GM brand like Buick, did the same thing in 2020. The result? Its dealer network across the nation reportedly thinned by a third.

Then there’s the issue of how cars are actually sold. Tesla famously pioneered a new model of selling vehicles that cuts out the dealership altogether and sells directly to the consumer. While laws on the books make it all but impossible for traditional car manufacturers to sell direct to consumers, other electric car companies such as Rivian and Lucid have followed Tesla’s path.

At the same time, the advent of massive online used-car dealers like Carvana and Vroom are stealing market share from local, independent used-car dealers and are especially popular among a younger generation that is more comfortable making purchases online. In 2020, nearly 30 percent of new-car purchases nationwide were made online (compared to less than 2 percent in the years prior). In 2022, that figure jumped to 66 percent.

If all of that weren’t enough, there are some local trends that could soon chip away at the power of car dealers. In 2020, local voters opted via a ballot question to expand the so-called right to repair, which requires all automakers selling new cars in Massachusetts to provide buyers with better access to their vehicle’s computerized data. That means the dealers don’t hold the only keys to the kingdom, and consumers can take their cars anywhere to be serviced. A national automotive lobbyist group representing automotive manufacturers is suing to have the law overturned.

To make matters more complicated, Governor Baker—the longtime dealers’ ally—is leaving office, and the person poised to take his place at press time, Maura Healey, has proven less friendly to the industry. She has more aggressive plans for reducing car usage and upping electric-vehicle adoption than Baker, and as attorney general, she has a solid record of going after dealers to defend the rights of car consumers. In September, she led a group of 18 attorneys general in urging the Federal Trade Commission to pass a stricter rule to protect car consumers, citing a whopping 3,036 consumer complaints in Massachusetts regarding motor vehicles in 2021 alone. That same month, she sued a car dealership in Haverhill for price discrimination.

In other words, the ground is shifting for Massachusetts’ once-unshakeable car industry, and it is unclear, once the dust settles, exactly what the industry will look like. But one thing is already clear: There will be fewer small dealerships.

Scott Dube is one of the many smaller auto dealers who recently made the tough decision to sell his Wilmington Hyundai dealership to a larger group as part of a widespread and ongoing process of dealer consolidation taking hold across the state. Dube is a second-generation dealer; his father bought the first family dealership in 1975, building a reputation in the industry from the ground up. His daughter, Emily, became the third generation, working alongside him, and he hoped that one day his granddaughter would be the fourth. But in May, he sold to the McGovern Automotive Group, which operates a few dozen stores in Massachusetts and surrounding states. “I would call it a really, really difficult decision because, with my daughter working with me, we had other plans,” Dube says, adding that he is still involved with the business. But “the competitive pressure working against massive companies and also the industry regulations coming from Washington DC, and here in Mass., those things start to add up after a while…. If you’re smaller, it gets harder and harder to work under that pressure.”

Dube believes the impact of industry consolidation will be felt across the state. “I think we’ll see much less of the local king of radio and the car dealer sponsoring the town baseball team,” he says. “It’s a loss for the community.”

In today’s climate, it seems that only the largest groups— national chains, Chambers, and those who would succeed him—and healthy midsize dealerships will survive. There is little doubt that Chambers is going nowhere. Meanwhile, the path to success for the next generation of dealers appears to lie in growth through acquisitions. That process is paving the way for a new crop of Automile kings to emerge. But given the changing landscape, they’re likely to look a bit different than the ones who came before them.

Chris Dagesse’s company acquired Boch Toyota, pictured, and Boch Honda, among other dealerships formerly owned by Boch father and son—both of whom rose to the level of local celebrities. / Photo by Christopher Churchill

Boch Honda. / Photo by Christopher Churchill

One day in late summer, I found myself riding down the Automile in the rain to the beat of windshield wipers flailing wildly. This famous section of Norwood sprawl has long been the car brands competing head-to-head for customers with flashy advertising campaigns. I passed several different Boch signs before reaching my destination, on a side street off the main drag.

I wasn’t here to visit anyone particularly well known around Boston. In fact, until I found myself standing in front of Chris Dagesse, the president of DCD Automotive Holdings, I had no idea what he looked like. I hadn’t seen his mug in philanthropy-circuit pictures, nor had I heard his voice on the radio. I was there because, despite all that, DCD happens to be the second-largest locally based dealership group in the state, behind Herb Chambers, with some 21 dealerships operating under the brand Nucar. In other words, Dagesse is the biggest car dealer you’ve never heard of.

Seated in his desk chair, the blue light from his dual monitors reflected in his glasses, Dagesse begins our conversation with a proclamation: “I love data.” It isn’t exactly the making of a famous tagline, and you surely won’t see Dagesse jumping out of any car trunks. Neither caricature nor character, he is forging a new path toward a quieter and, dare I say, nerdier kingdom on the Automile that relies more on technology and less on personality.

A self-professed computer guy, Dagesse is investing in developing new software for his dealerships, not in advertising his brand, or himself for that matter. In fact, the Nucar website doesn’t even mention his name. “Our technology and software that we’re building,” Dagesse says, “will actually give us a leg up and put us in a better position to keep our profitability with the changes like Ford’s.”

It’s not just dealership owners that need to evolve. Ray Ciccolo, the founder and owner of the Village Automotive Group and a dealer of nearly 60 years, says the times call for a data-focused approach at all levels of the dealership. “We now need a different type of salesperson,” Ciccolo says. He describes this seller as an “information person,” someone who has technological skills and can bring customers along at their own pace and do most of it electronically.

To accomplish that, Dagesse is harnessing tools similar to the ones Carvana and Tesla use in order to build his own software platform. Low-maintenance dealership homepages typically send visitors to third-party sites that he says are “franken-bolted” on in order to showcase inventory or continue the car-purchasing process. By contrast, Nucar’s software, which is still in the testing phase, is baked into the dealership’s website and offers appraisals of vehicles across multiple sites and platforms, including Carvana and CarMax, allowing customers to compare prices around the Web with his own dealerships. It also offers consumers the ability to compare financing options across different banks. Dagesse says his site is designed to make the car-buying process as short as 29 minutes. That said, the guiding principle isn’t just ease and speed, but also full transparency.

Dagesse’s investments don’t just benefit customers, of course. Over the past few years, he has been quietly positioning himself as the heir to the Automile throne. Similar to other dealership consolidators snatching up smaller companies, he has made a series of dealership acquisitions, including buying out several of Boch’s stores.

Still, no dealer, no matter how big, is immune to the changes on the horizon and will have to adapt to survive. At press time, Dagesse, like other dealers, was cautiously weighing his options regarding Ford’s ultimatum, the hefty investments required, and the impact it may have on the future of the dealer-manufacturer relationship. But I got the feeling that the forward-looking Dagesse is the kind of dealer who will do what it takes to get there—even if it means going electric.

When the rain finally stopped on the day of my visit, Dagesse suggested we get out of the office and go for a test drive in a new car. Of all the cars he could have chosen on the lot, he chose the fully electric Ford F-150 Lightning that the manufacturer had sent him as a promotional vehicle. As the storm clouds cleared from the sky, we clambered into the truck and set out for a ride down the Automile