Inside Boston’s Mysterious Drink-Spiking Crisis

Hallucinations downtown. Blackouts in Brighton. Trips to the ER all over the city. What is happening in Boston's nightclubs?

Photo by Joe St. Pierre / Styling by Joy Howard / Model: Jacob Heart

On a cool October night, the second floor of a downtown bar was thrumming with weekend partiers blowing off steam after another long week of work and school. That included 23-year-old Peter. The young professional, whose name has been changed to protect his identity, was excited to be out like any other weekend. Surrounded by friends and friends of friends, he strained to hear the conversation over the loud pulsing music. Might as well get another round of drinks, he thought, before peeling away from the group and wading through a dense throng of twentysomethings toward the bar.

Pressed between the wooden edge of the bar railing and the bodies behind him, Peter made eye contact with the bartender, asked for three cocktails, and waited until the barman returned into view and handed him the drinks. Peter jostled his way back to the group, managing not to spill more than a few drops, and offered one of them to a girl he had just met. He didn’t know her well, but they had been talking for the past hour, and it seemed like a nice gesture.

She was wary at first. After all, Boston police officials had recently warned of a rise in drink-spiking cases across the city. “Don’t allow people you don’t know or trust to order drinks and deliver them to you,” one of the many community alerts read. So she asked Peter if he would split the drink with her. He happily agreed. Moments later, though, as the contents of the cup dwindled down to melted ice and they each took their final sips, Peter announced: “Something was wrong with that drink.” It was the last coherent thing he said.

As his friends later told him, Peter started acting weird. At first, he was quiet, barely uttering a word for more than an hour. They didn’t realize he was trying to speak but couldn’t form the words. At one point, he had so much trouble talking that he tried to type out a plea for help on his phone, but his fingers struggled to find the right letters. His friends assumed he was very drunk.

It was only when Peter’s drink-mate began violently vomiting that Peter’s friends finally understood something was wrong. By then, almost two hours had passed since Peter had finished the drink that he’d said seemed off, yet he wasn’t sobering up. He couldn’t even make it out of the bar on his own two feet. He bobbed and weaved toward the exit, unable to keep his legs moving in a straight line, and never made it to the door. Instead, he flopped over a railing inside the bar and stayed there, trying to support himself while his friend dialed 911. The ambulance never came. Eventually, Peter’s parents arrived from the suburbs south of Boston and rushed him to a hospital.

It was after 3 a.m. by the time Peter entered the emergency room—now three hours since he’d had anything to drink—and he was hallucinating. Under the unforgiving bright lights of the hospital room, he was gripped with panic. He fought off nurses, believing they were demons from The Lord of the Rings. He spoke gibberish. He invoked spells from Harry Potter in a fruitless attempt to vanquish his doctors, who were forced to put him in restraints.

The symptoms Peter’s friend and family later described to him matched those of the common date-rape drug GHB (gamma-hydroxybutyric acid). Unfortunately, he will never know for sure. Nurses at the hospital, he says, didn’t test for date-rape drugs, explaining to his parents that too much time had passed to accurately detect them in his system. The nurses’ possible skepticism may have also played a role in the decision not to test. Jotted in Peter’s medical record under the space for “attending reason” was a note that said: “Someone spiked his drink?”

Peter’s story is hardly unique. In 2022, the Boston Police Department received 116 reports of incidents involving contaminated or “roofied” drinks. Yet these cases represent only the tip of the iceberg. Last fall, legions of people took to social media to post stories that sounded a lot like Peter’s: I only had two drinks. I passed out in the bathroom. I couldn’t move my legs. I don’t remember anything. Like Peter, the majority of victims didn’t file a police report, and for those who did go to the ER, few were tested for date-rape drugs.

In no time, Bostonians who believed they’d been drugged began to find each other online. By May, a private Facebook group dubbed “Booze in Boston” had formed, becoming an unofficial ground zero for sharing experiences of drink spiking in Boston (today, it has close to 11,000 members, including victims, witnesses, and concerned residents as well as a crowdsourced list of more than 70 bars and nightlife venues where incidents were reported to have occurred). Later that same month, a TikTok video (embedded above) of a young blond woman in a hot-pink sweatshirt appeared under the headline “Roofies on the Rise in Boston.” For three minutes, her image was superimposed over a slideshow of social media posts by people saying they’d been roofied at local bars while she summarized for viewers the contents of each report. The video soon went viral, garnering 613,000 views and nearly 1,500 comments—many from people describing eerily similar experiences. Drink spiking had had its #metoo moment.

The stories were striking, not only because of what happened but also what didn’t happen: The vast majority of people who reported being drugged were not sexually assaulted or even robbed. Make no mistake: Tampering with someone’s drink is a crime, but it’s most often committed to facilitate crimes, such as robbery and rape (hence the moniker “date-rape drugs”). This, along with a dearth of incontrovertible evidence, has introduced doubts among some experts, making it hard not to wonder: Are the city’s young partiers being paranoid, or is something sinister happening at night?

Music venues and bars (including Roadrunner, pictured here) are making drink lids available to customers and posting warnings about how to stay safe. / Photo by Phil Wikina

Skye can remember every word of Bonnie Raitt’s song “Nick of Time,” but she cannot remember anything that happened after listening to the band Lake Street Dive perform it at Roadrunner in Brighton last June. The floor was packed as she faced the stage and belted out every word of the ’90s hit—but after that, her world faded to black. “It was like a curtain came down,” she says. For a while, Skye—whose name, like other victims in this story, has been changed to protect her privacy—seemed okay, talking, joking, and enjoying the concert as if nothing was wrong. But when the concert ended and she and her friends went outside, Skye started babbling incoherently.

Her friend helped her into an Uber and begged Skye not to throw up, but just two blocks from her apartment, Skye bowed her head forward and vomited all over herself. They walked the rest of the way home, where Skye’s door camera captured her with her shirt off—presumably, she thinks, having taken the vomit-stained garment off while outside on the street. The next morning, after Skye regained consciousness, she began throwing up again and couldn’t stop, prompting a trip to the emergency room. “I’ve been drugged,” she told the staffers there. After all, she thought, there was no other explanation. Nurses treated her like any other patient, taking her vitals and administering antinausea medication through an IV before running a basic blood test and a urine toxicology screen for common drugs such as cannabis, opiates, and cocaine. The tests came back negative for everything.

There was one thing, though, that the hospital staff did not do: test Skye for common date-rape drugs such as GHB, ketamine, and Rohypnol. Still, even if she had been given such a test, it might have come back negative. While drugs such as cannabis, cocaine, and opiates are detectable for more than 24 hours in the human body, commonly used date-rape drugs have a significantly shorter half-life, meaning they can be undetectable by morning. “There’s a perception that we can just test you, that if there’s something in your blood that doesn’t belong there, we’ll find it,” says Matthew Mostofi, associate chief of emergency medicine at Tufts Medical Center (Skye did not go to Tufts for care). But “most of these drugs get metabolized, and they’re not there 24 hours later.”

That’s not the only reason doctors didn’t test Skye for date-rape drugs. As Mostofi notes, the tests are not only impractical in most cases, but also expensive. They’re often only administered in instances of sexual assault. “Insurance companies are going to say, ‘Why am I paying for some test that doesn’t directly involve your health?’” he explains. So instead, staffers at the ER Skye visited did what they usually do in these cases: treated symptoms and provided any necessary medical care. “I asked for a more in-depth test, and the medical staff at the hospital pretty much said they couldn’t order it unless I was assaulted, unconscious, or dead,” she says. “Even if I wanted it, they said it would cost me hundreds of dollars.”

A public safety notice at Grendel’s Den in Harvard Square from earlier this month. / Photo by Makena Gera

Some people do manage to get the right tests, either by demanding them or by going to a hospital with a more forgiving policy. Still, they are the exception, not the rule. Of the 116 drink-spiking cases reported to the BPD in 2022, only 10 of them involved someone who had a positive toxicology screen for anything from ketamine to GHB and Rohypnol. Cambridge police, meanwhile, wouldn’t share how many cases of suspected drink spikings have occurred in their city, saying only that of the unstated total, one victim tested positive for GHB. The remaining accusers had no chemical evidence to support their claims.

All of this makes finding out what’s actually happening in Boston-area bars, nightclubs, and concert venues even more difficult: Not only is the motive a mystery, but the hard evidence that drink spikings even occurred at all is elusive. Without the easy ability to gather evidence proving they were drugged, many people choose not to go to the police, fearing the cops either won’t do anything or won’t believe them.

That was what Julie thought after she had a drink with a few friends at a Seaport bar. “I went from feeling totally coherent to just absolutely nothing,” Julie says. “There was no gray area in between.” After they called an Uber and left the bar, one of Julie’s friends began vomiting on the street. When they made it back to another friend’s apartment, Julie also started throwing up repeatedly until she passed out—only to wake up at 1 p.m. disoriented and with no memory of how she got to her friend’s house. Julie was sweating and had chills that lasted nearly 12 hours. She says she consumed only three drinks over the course of four hours and can’t remember the last time she had gotten drunk to the point of vomiting. Still, she didn’t go to the ER or the police station to report it. “Part of me was so freaked out by the experience that I didn’t want to go to the police and deal with someone telling me that I was just drunk,” she says.

City officials, though, are urging victims to report being drugged. “We want to make sure that people trust the process enough that they go through with it, so that we better understand what’s actually happening, as opposed to operating based off conjecture and assumptions,” says Segun Idowu, chief of Boston’s Office of Economic Opportunity and Inclusion, which is spearheading the city’s response to the spiking incidents. “If you’re going to say something on social media, that’s your prerogative. At the same time, we want people to be comfortable enough to alert a local police station.”

Members of the Boston Police Department agree. Sergeant Detective John Boyle says officers are more than willing to believe people who say they were roofied. “We’d rather things be overreported than underreported,” he says. “Every little pebble in an investigation helps.” Telling police about an incident, he explains, can assist in other cases, whether it’s helping officers detect patterns in drink spikings at specific venues, bars, or restaurants or preventing someone else from being drugged in the same location.

And reporting any suspected drink tampering may be more important now than it ever has been before. Prior to 2022, the BPD was not aggregating cases related to drink spiking. In the department’s reporting system, there was no category or “check box,” per se, to flag these incidents. As a result, cases couldn’t be codified, meaning they were essentially lost in the system. It wasn’t until a few months ago that a coding system was implemented, offering a “huge step forward” for investigations and tracking cases, says Lieutenant Richard Driscoll of the BPD’s sexual assault unit. So far, a retroactive search of BPD’s database for reports of drink spiking found only a handful of cases in 2020 and 27 cases in 2021, in addition to the 116 in 2022.

Still, justice has not yet come for the majority of victims. Despite the dozens of reported incidents in Boston last year, at presstime, the Suffolk County District Attorney’s Office has charged only one case involving a drink spiking, and it was a case that also involved a sexual assault. In that case, Robert McClanaghan, a Rhode Island resident, was charged with rape and “drugging for intercourse” in November after a woman claimed she was drugged in a Boston hotel, then raped in a hotel room. Investigators obtained surveillance video that they say shows McClanaghan sprinkling something into the woman’s drink. (McClanaghan has pleaded not guilty to both charges, and the case is currently pending.)

The Boston police’s Driscoll and Boyle, as well as Ian Polumbaum, chief of the Suffolk County District Attorney’s Office Special Victims Bureau insist that just because someone was not physically or sexually assaulted doesn’t mean they weren’t harmed or that a crime wasn’t committed. It’s just unless the perpetrator is caught pretty much red-handed, there is nobody to charge. Still, the high rate of reports with zero prosecutions in cases solely involving spikings has given rise to other theories about what is really going on in Boston after dark.

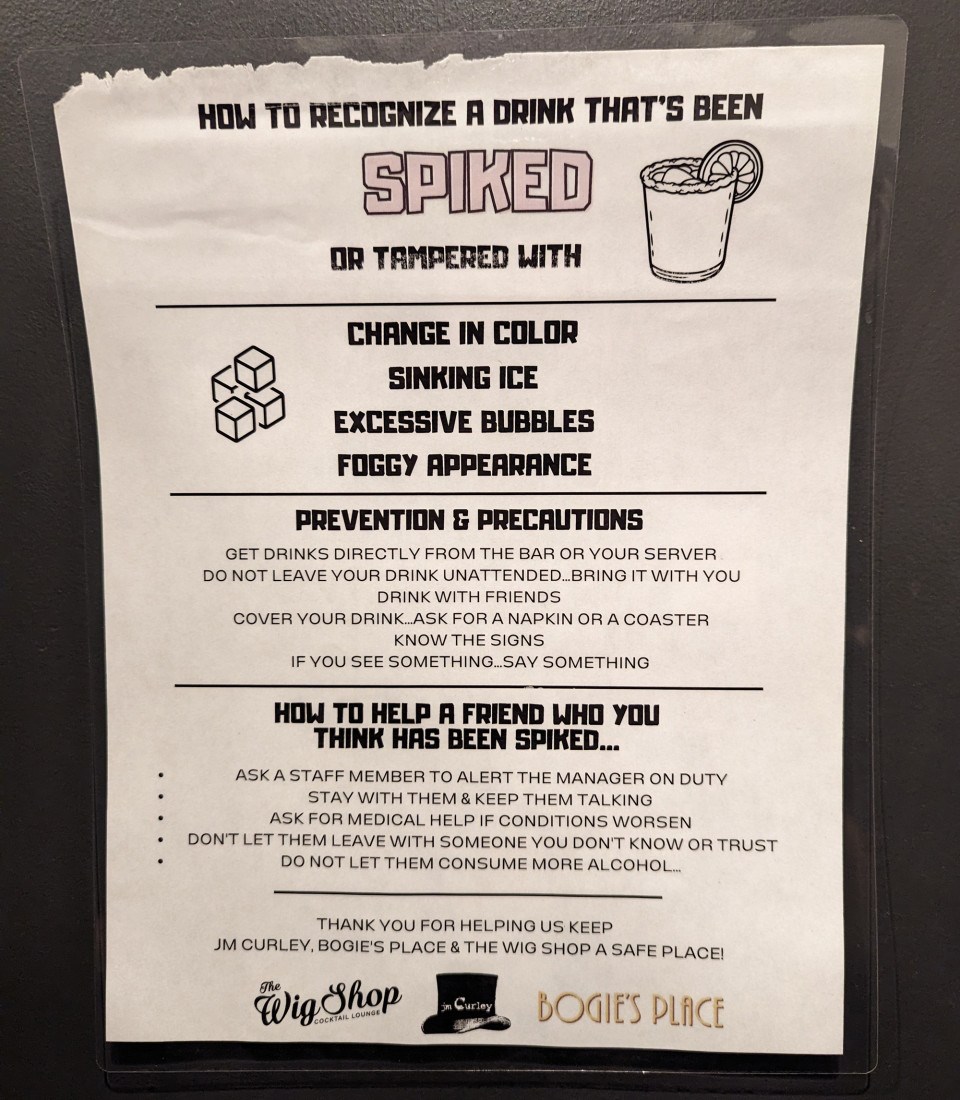

In January, a sign posted on the back of bathroom-stall doors at Boston bar JM Curley warned patrons about drink spiking. / Photo by Rachel Leah Blumenthal

When Skye finally felt well enough to pull herself out of bed after that blackout night at Roadrunner, she did what so many others have been reluctant to do: She picked up the phone and called the police. The investigation that followed, though, raised more questions than it answered.

A detective watched security footage from the night Skye was at the music venue and painstakingly put together a timeline of her exact movements throughout the evening: The precise minute she went to the bar to get each of her drinks, which bar she ordered from, and which bartender served her over the course of two hours. In the footage, Skye flitted in and out of view as she made her way onto the dance floor, walked to the bathroom, and talked to her friends. Police found no strange interactions and no mishandling of her drinks. In fact, Skye says she kept her hand over her drinks the entire night and never let them out of her sight. In other words, she did everything right. And more to the point, there was no evidence that anyone did anything illegal. The Bowery Presents, which owns Roadrunner, has fully cooperated with police investigations, including providing security footage when requested by law enforcement. The venue operator says they have implemented awareness trainings for bartenders, security, and staff, as well as new protocols including readily available drink covers for patrons who request them. Guest safety and security, they note, is their highest priority.

Safety Guide for Public Drinking seen at Roadrunner

by u/shminkydink in boston

As in Skye’s case, other victims have reported scenarios in which it seemed highly improbable, if not impossible, that anyone had access to their drinks. Julie and Peter got their drinks straight from the bartender. Four other people also said their drinks went straight from the bartender to their hand and remained there the entire time, oftentimes covered by their hands and, in one case, drink covers provided by the venue.

This baffling set of circumstances has prompted some victims—and many online commenters—to question whether it is the bartenders themselves who are spiking other drinks. Yet what reason would a bartender—stuck behind a few feet of hardwood and looking for good tips—have to drug customers? And even if there were one or two bad apples among our city’s massive fleet of barkeeps, that wouldn’t explain how 70 venues landed on the crowdsourced list of places where incidents allegedly occurred. As of December, Boston’s Licensing Board, which regulates alcohol and food licenses, held eight hearings regarding alleged drugging incidents in 2022, finding that none of the premises investigated were responsible for the drink spikings taking place on their property, as none of the spikings were proven.

With no proof, no apparent motive, and, in many cases, no window of opportunity to commit a crime, an army of armchair detectives have turned the table on the victims to come up with other explanations. Some posit that revelers simply lost track of how much they drank, were lightweights unable to hold their liquor, or couldn’t handle the effects of mixing alcohol with (now legal) high-grade marijuana. In other words, they were just trashed. “There is a pretty straightforward explanation here,” wrote one person on a Reddit thread about the topic, “especially for new college students who don’t have experience binge drinking.”

Commenters also questioned the pandemic’s role in the epidemic. Might there be an unexamined negative interaction between alcohol and a recent COVID booster? Could some of the victims have unknowingly had a case of long COVID, exacerbating the inebriating effects of their beer or cocktail? Others suggested the recent spate of blackouts could be the well-documented adverse effects of mixing alcohol with antidepressants or antianxiety meds that legions of people started taking mid- and post-pandemic. Still, there is another, more academic, theory of what the drink-spiking crisis might be about, and it’s one that cannot be easily dismissed: social panic.

Robert Bartholomew, a sociologist and honorary senior lecturer at the University of Auckland, believes what is happening in Boston has all the hallmarks of mass hysteria, defined as widespread public fear based on false or greatly exaggerated perceptions of danger. He has studied and written about this phenomenon several times—including a mystery illness that befell American and Canadian diplomats in Havana and a case of chronic vocal tics among students at two high schools in Massachusetts in 2012 and 2013. He says a huge red flag concerning the roofie epidemic reported in Boston—and L.A., Denver, and throughout the United Kingdom—is that there “are a whole bunch of reports, a handful of arrests, and very few, if any, convictions.”

Even if Bartholomew is right, that doesn’t mean people aren’t getting their drinks spiked in Boston; it’s just that the incidents are likely occurring far less than social media posts would lead anyone to believe. “These outbreaks are triggered by an initial sensational case that gets high-profile media coverage,” Bartholomew says, adding that social media is likely fueling the phenomenon and putting people on high alert. This, in turn, leads people to scrutinize their environment for evidence of some dangerous person trying to harm them.

Whatever is happening, he says, likely has a far simpler explanation: Perhaps partiers had more to drink than they remember, or a medication they took interacted poorly with alcohol. Maybe they didn’t eat enough before drinking. But because they are hyper-alert to the reports of cases, they assign blame to some dangerous person. He notes that a small number of cases might very well be bonafide drink spikings, which only fuels the panic.

Social panic is something we have seen throughout history. “From time to time, societies are gripped by the fear of some nefarious agent who is going to bring down the normal social order,” Bartholomew says, adding that as with the Red Scare, the Anthrax panic, and other mass hysterias, the concern that it is not safe to go out and drink in Boston comes on the heels of a long period of fear and uncertainty, this time due to the emergence of COVID. “It may be no coincidence that the spiking epidemic has coincided with the easing of pandemic restrictions,” he says. Bartholomew believes that the recent increase in reports of spikings in L.A. and Denver, and even reports of people being injected with date-rape drugs in the U.K., all bear the hallmarks of a post-pandemic social panic.

Still, the social-panic theory itself has limitations. Many victims described symptoms that aren’t typical of simply having too much to drink, including hallucinations and physical ailments that lasted for days. What’s more, the people who claim their drinks were spiked include men and older women who do not fit the typical victim profile and, therefore, probably weren’t primed by the suggestion this could happen to them.

Making Bartholomew’s theory even more vexing is that there is no way to prove definitively that something is a social panic other than to rule out every alternative explanation. And that isn’t happening in Boston because people aren’t getting tested fast enough, if at all. Still, if all goes according to the city’s plan, that could change.

Photo illustration by Benjamen Purvis

During a city public safety and criminal justice hearing in October, City Councilor Gabriela Coletta made a startling admission: Someone had roofied her when she was in college as an undergrad. “You expect to go out and have a great night, only to have it completely derailed,” she said. “It can happen to anyone. It happened to me.”

More than a dozen somber-faced officials, ranging from the city’s Licensing Board and the Boston Police Department to local colleges and advocacy organizations, stared back at her on Zoom, feeling the power of her unexpected words. Now, nearly a decade after being drugged, Coletta told the crowd that she is overwhelmed with emails about drink spiking and is constantly being tagged on social media posts by women who have just experienced what happened to her many years ago.

The meeting marked an important moment: It was the first public attempt by government officials to truly address what was going on at night in Boston. Already, police had issued alerts, and city bars and music venues had begun taping warning posters to the inside of bathroom stall doors. Yet now it was finally time, Coletta said, to stop placing the burden of behavior change on victims.

In the months that followed, officials began talking about changes that bars and venues could make so that staff could more rapidly recognize and aid customers who may have been drugged. That was welcome news to then-22-year-old Annie, who believes she was roofied in the fall of 2021 at a bar on Lansdowne Street in the Fenway. In her final moments before blacking out in the bar, she remembers staggering into the bathroom, unable to keep her balance. A friend who followed her to see if she was okay says she watched as Annie threw her phone across the bathroom, sending it skidding across the floor. From there, Annie rushed to an empty stall and leaned over the toilet to vomit.

An official PSA from the City of Cambridge

A female bouncer also followed Annie into the women’s bathroom, but she wasn’t there to see if she could help. The bouncer, says Annie and her friend, was there to let Annie know that she’d get the boot if she couldn’t stand up on her own. Yet for Annie, that was out of the question. She was mumbling to herself and barely hanging onto consciousness. Before they knew it, Annie and her friend say, the bouncer had hauled them both out of the bathroom, through the pub’s kitchen, and out the back door into the alley, leaving the pair outside, alone, in the dark.

Bouncing sick or troublesome patrons is often the response at bars and nightclubs, where fear runs deep of being sanctioned by the Licensing Board for overserving—or appearing to overserve—a customer. That night, the bouncer apparently thought Annie had had too much to drink—though Annie insists that was not the case. It’s hard to tell the difference between someone slurring and stumbling because they’re drunk and someone doing the same because they’ve been drugged, especially without any training. Still, Annie says, “there needs to be a system put in place that isn’t just kicking you out to the alley. How do you make sure that person is okay?”

The city is trying to come up with that system right now. In December, the Licensing Board and the Office of Economic Opportunity and Inclusion recommended a “Nightlife Safety Pledge” for venues licensed to sell alcohol: It would include staff training focused on recognizing someone who has been drugged. It also called for installing more cameras near the bars, providing lids for drinks, and ensuring that patrons know they’re available. At presstime, the pledge was being drafted and tested with licensees. At the same time, Idowu says that the city is working to secure funding to equip emergency medical responders with toxicology tests so that when someone calls 911 while out at a bar, an EMT could administer a test on the spot while the drugs may still be in their system. Even the state legislature is keen to find a fix: In late January, state Senator Paul Feeney filed a bill that would, among other things, allow the Department of Public Health to require hospitals to test victims for date-rape drugs at the request of any patient exhibiting symptoms.

City officials are right to be concerned about a possible drink-spiking epidemic for reasons that go beyond people’s health and safety. Boston’s nightlife scene is finally thawing after a COVID-induced deep freeze, and on March 6, a new nightlife czar (formally known as the director of nightlife economy under the Office of Economic Opportunity and Inclusion) will begin working to shake Boston’s reputation as the city that sleeps. Better nightlife not only helps Boston’s economy by supporting individual businesses that pay taxes and hire people; it also makes Boston a more attractive place for young people to relocate. Idowu knows that the city’s efforts to promote nightlife will be meaningless if people are afraid to go out.

In an effort to stay safe and band together, some partiers are taking matters into their own hands. As they get ready for an evening out, they are loading their purses with reusable drink covers and test strips that can detect date-rape drugs. They are also doing the only other thing they can think of to prevent this from happening to others: telling everyone they know to be careful, because Boston appears to be in the grips of a spiking epidemic. Will that help protect people from danger? Or will it only create more paranoia, fueling reports of even more spikings that may not have happened? For now, that, too, remains a mystery.

A version of this story appeared in the print edition of the March 2023 issue, with the headline “Drugged?”