The Real, Essential Backstory of ‘the Embrace’

To some, the new monument to Martin Luther King Jr. is a symbol of love, unity, and overcoming the city’s racist past. For others, it’s a sign that Boston hasn’t learned anything. But few know the polarizing public sculpture's true significance.

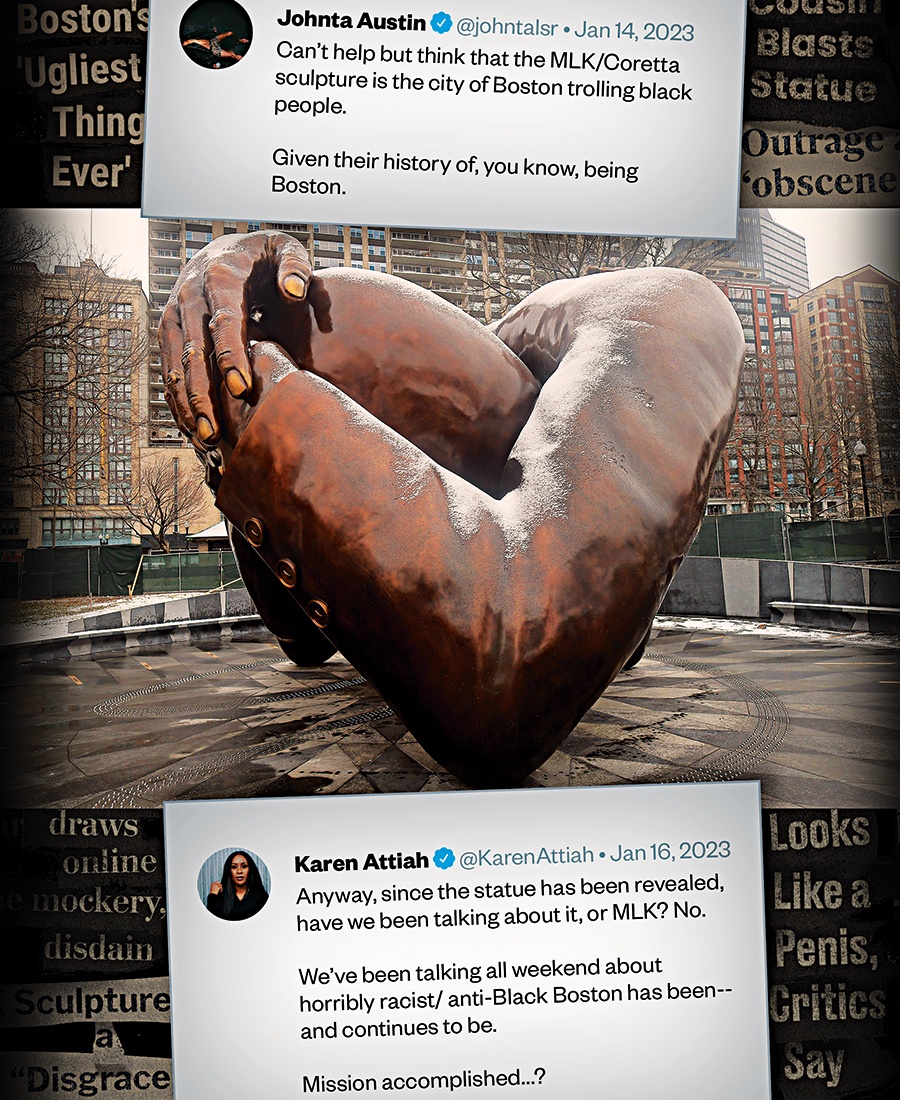

Photo illustration by Benjamen Purvis / Sculpture photo via Boston Globe/ Getty

The ceremony that took place before the monument to Martin Luther King Jr. and his wife, Coretta Scott King, was revealed had all the hallmarks of a major affair. The program was studded with speeches from dignitaries, including members of the King family. A choir sang. The media aired the event live. Then came the moment everyone had been waiting for: the unveiling. People in attendance gathered around the still-shrouded monument and began a countdown. Five, four, three, two, one, and the black fabric covering the statue slithered to the ground, revealing the newest gleaming bronze addition to Boston, where the Kings met and lived for a time. Cameras snapped, the crowd cheered, and people held one another in the shadow of The Embrace.

The monument is a figurative depiction of an iconic photo taken of the couple after King learned he had won the 1964 Nobel Peace Prize, and includes only their arms and hands in a suspended embrace that, seen from one side, takes on the shape of a heart. Designed by renowned conceptual artist Hank Willis Thomas, it was meant not just as a testament to the couple’s love story but, more broadly, to the power of Black love itself. Bostonians had grand ambitions for it: Imari Paris Jeffries, the executive director of Embrace Boston, which organized the effort, has said that “It is Boston’s Statue of Liberty.”

As I watched the unveiling, I felt a great sense of joy and pride, and not just because Boston had (finally) properly and permanently honored a Black hero with Boston ties on the grounds of the oldest public park in the United States. My emotions also reflected the fact that this monument represented an opportunity to accomplish something I’ve been trying to do for years through my work in the media: show the rest of the country a new side of Boston, one that might change the persistent perception that Boston’s non-White community is nonexistent and the never-ending narrative that our city is plagued by uniquely high levels of racism.

My expectations were short-lived. Within no time, a memorial that was designed to transmit a message of love from Boston to the world was garnering untold amounts of online hate—much of it directed at the city itself. Some people just didn’t like the look of it, which is to be expected with any piece of high art. But then things took an unexpectedly salacious turn, as people online started pointing out that some angles of the disembodied arms and hands—as seen in photos circulating on the Internet—appeared pornographic. That is when the criticism went viral, and the monument became a source of mockery. “In time, we will see this statue for what it truly is,” said Leslie Jones on the Daily Show. “Martin Luther King going down on his wife.” Her correspondent, comedian Dulcé Sloan, remarked that from another angle, The Embrace “looks like hands cradling a big penis…. No matter which way you look at it, it’s a different erotic act. Like a sexual Rubik’s Cube.”

As I watched all of this unfold from the tiny screen of my phone after having witnessed the joy of the unveiling, I fired off a tweet that said, in part, “Jesus, send the meteor.” Perhaps not surprisingly, even that tweet was twisted by Trump loyalists and Proud Boy supporters as a call to destroy the monument. Instead, it was a frustrated plea to end humanity for being so ignorant and disappointing. These people were under the impression that this monument was created without Black Bostonians spearheading the effort, leading the charge, and making the creative decisions themselves—and that upset me to my core.

I and others had hoped that The Embrace and everything that went into the effort would show the nation another side of a city that, while it has been plagued with racial biases, sought to honor someone who residents of the inner city of Boston have seen as an honorary Bostonian for more than three generations now. It turns out that people were too blinded by their own biases about Boston to see it.

What became obvious early on in the social media frenzy was that many of those commenting from outside of Boston had no idea what they were talking about.

The iconic 1964 photo inspiration for ‘The Embrace.’ / Photo via Getty Images

What became obvious early on in the social media frenzy was that many of those commenting from outside of Boston had no idea what they were talking about—either about Boston’s Black history or the process undertaken to honor King with a monument. The fact is, the process that culminated in the monument being erected on the Common was a model one.

It started five years ago with a yearlong design contest held by what was then called King Boston in conjunction with the Boston Art Commission. Entrepreneur Paul English and Reverend Liz Walker, cochairs of King Boston, along with Boston Art Commission vice-chair and visual artist Ekua Holmes, released a call to artists to present monument design proposals. Then a committee comprised of well-regarded educators, artists, and curators, many of whom are Black, and all of whom had deep knowledge of Black art, narrowed the field of 126 applicants to five finalists.

The next phase brought the broader community—with a focus on Black Boston—into the decision-making process. The five finalist designs were all posted online as well as publicly exhibited at the Bruce C. Bolling Municipal Building in Nubian Square, arguably the heart of Black Boston, and at the Boston Public Library in Copley Square to garner public feedback. After amassing and taking into consideration more than 1,000 public comments about the final contenders, the committee further whittled it down to the three most feasible and practical designs before choosing Thomas’s design as the winner.

In many ways, he was an ideal artist for the task. He is known for framing Black subjects throughout history by using an abstract style, and he has regularly used art to address the way that inequality and bias are perpetuated by visual representations. After reviewing the design multiple times, the Boston Art Commission unanimously approved The Embrace.

Throughout all of these rounds of scrutinizing the design, its feasibility, and its aesthetics, no one at any point in the process felt the monument was or could possibly be construed as erotic, sexual, or vulgar in any way. Nor did anyone feel it disrespected King’s legacy—not even the people most invested in protecting that legacy: The King family was involved throughout the process, and none of them ever voiced any issues with the winning design or the vision behind Thomas’s creation.

Every aspect of the monument, from its design to its siting, is imbued with an awareness of Black Boston history, a history that many outsiders making comments (and many Bostonians) know nothing about. Hank Willis Thomas’s intention behind the creation of The Embrace was to highlight Black love and the concept of Black joy in close proximity to the Boston Common’s numerous monuments to war heroes and military leaders. Placing a sculpture depicting the love of a couple who sought to hold each other up during their much-challenged and pacific fight for civil rights and equal protection under the law for their people was a contrast—and a valuable addition—to what was already there.

On April 23, 1965, Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., addressed a large rally at the Boston Common, after completing a protest march from Roxbury. / Photo by Bettman via Getty Images

In fact, this particular site within the Common is heavy with meaning. It is located on the spot where on April 23, 1965, King addressed more than 20,000 people whom he’d just led on a march from Roxbury to the Common to protest inequities Black people faced in Boston. If you look down, the surface of Freedom Plaza around The Embrace lists the names of 69 Boston and Massachusetts civil rights leaders and advocates for social justice who were active between 1950 and 1970, fighting to transform the face of the state during one of the most tumultuous stretches of recent history.

Some people criticizing the monument said that the $10 million spent on it would have been better spent on efforts to close the equity gap between Boston’s Blacks and whites. Again, they missed a big part of the story. Embrace Boston also conducts policy research on topics of importance to Black Bostonians, such as reparations. It has a media project that includes a podcast featuring prominent Black Bostonians. It also includes a fund that channels money to organizations working to close the equity gap.

For all of the above reasons, when I was asked to participate in a documentary and podcast created for release ahead of the monument’s unveiling, I was extraordinarily proud to accept.

While Boston struggles with unacceptable levels of inequity, it is now a place that recognizes that big, bold monuments to Black heroes have a place on the common.

My career as a writer and a historian has been dedicated to telling the stories of Black Boston, especially through the lens of my South End/Lower Roxbury neighborhood, the very place where Martin Luther King Jr. and Coretta Scott King lived, met, fell in love, and began their married life together. That’s why when King Boston, as Embrace Boston was known at the time, asked me to provide additional context about King and Scott’s time in Boston, I jumped at the opportunity. I appeared in the short documentaries Voices on King 2022: Reflections on Black Boston and Embrace: the Kings, and am featured in Embrace Boston’s podcast Good Trouble in an episode titled “Born and Raised in Boston.” My voice and words appear in the digital experience that you can access through a handheld device at the monument.

I saw my participation as a chance to tell some of the many stories that Black Bostonians have been telling for the past five decades, but that haven’t received a lot of national attention. These are the kinds of stories that create a fuller history of Boston.

King leading the April 1965 protest march from Roxbury to Boston Common. / Photo via Getty Images

As the unveiling of The Embrace drew closer, I found myself thinking a lot about another piece of history from Black Boston that most people don’t know anything about—and after seeing the reaction to The Embrace monument, it seems even more important than ever to remind them of it.

Less than a few hundred feet from where The Embrace now stands is another monument. It was intended to be dedicated to a famous Black hero from Massachusetts who briefly resided in Boston. His name was Crispus Attucks, and he became the first casualty of the American Revolution when he was gunned down in the Boston Massacre. Some 80 years later, in 1851, Black leaders William Cooper Nell, Charles Redmond, Lewis Hayden, and Joshua B. Smith brought the idea to the Massachusetts legislature to erect a monument to Attucks on the Common, among other statues of American heroes. They were unable to get the legislature to act and designate public funds to build and install the monument. It was only some 40 years later, after Black and white abolitionists and Boston’s Black community supported the effort, that the monument made it to the Boston Common.

Still, when it was finally erected, it was nothing like what they had envisioned. The statue was not a monument to Crispus Attucks but to all five men gunned down in the Boston Massacre. No graven images of Crispus Attucks can be found anywhere on the monument. In its stead is an obelisk with a sculpture of a woman representing the spirit of revolution holding broken links of a chain above her head with her right hand while holding an unfurled American flag with her left, above an eagle with spread wings about to take flight. Attucks’s name is listed at the top of the obelisk with the other martyrs of the Boston Massacre.

That was, indeed, a story of the whitewashing of a monument to a Black hero, and this is part of Boston’s history. And while Boston, like every city in America, struggles with unacceptable levels of inequity, it is now a place that recognizes that big, bold monuments to Black heroes have a place on the Common. It is a city that listened to what Black Bostonians wanted the monument to look like and entrusted Black Bostonians to lead the process to make it happen.

Nevertheless, it seems we still have a long road ahead of us before the rest of the nation believes our best intentions are genuine. And it will take far more work to get us there than installing one piece of public art. But it is a part of the process—a process we should all embrace.

First published in the print edition of the March 2023 issue, with the headline “Up in Arms.”