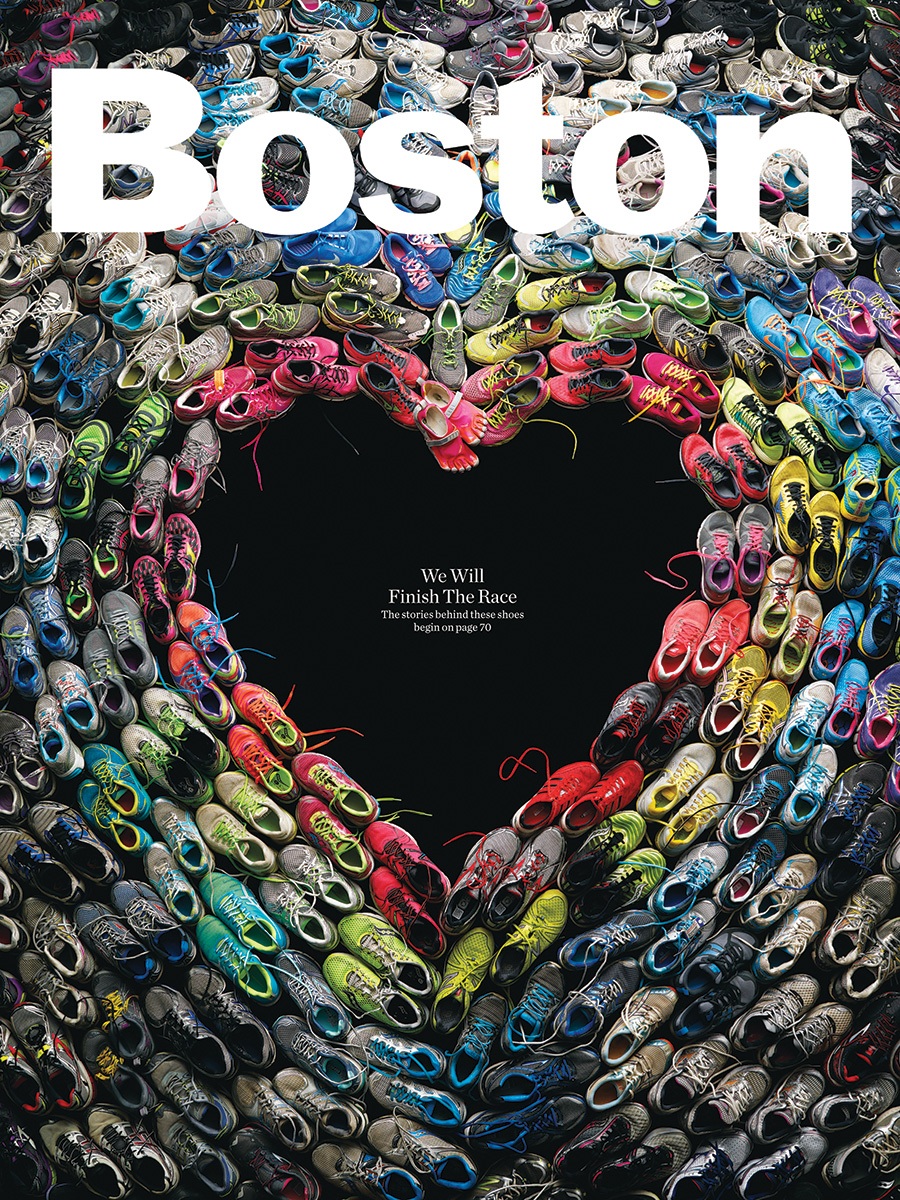

“We Will Finish the Race”: The Making of Boston’s Iconic Marathon Shoes Cover

Moments after the bombings rocked Boylston Street, and with less than a week until the presses rolled, Boston magazine’s staff knew they needed to create a new cover image for its May 2013 issue that captured the spirit of the city. The rest is literally history. Here’s how they did it.

Photo by Mitch Feinberg / Styling by Megan Caponetto

On the morning of Tuesday, April 16, 2013, National Guard members—still in shock from the previous day’s attack—patrolled the streets of the Back Bay, while FBI agents combed through the crime scene at the finish line. Meanwhile, inside the offices of Boston magazine at the corner of Huntington and Massachusetts avenues, two dozen staffers gathered near the editor in chief’s office. After all, there was a magazine to make. The May issue was due to the printer at the end of the week, and while most of its contents had already been finalized, the team of editors, writers, and graphic designers realized they basically needed to start over. But what could they put together in just three days?

By Friday, the magazine’s staff had created a cover image that would become a national topic of conversation, win multiple awards, and provide a bit of comfort to a city in desperate need of it. But on that Tuesday morning, having decided on a new way forward, none of that was on editor in chief John Wolfson’s mind as he laid out a singular mission that would require the entire newsroom: They needed to find some running shoes. Fast.

“We’ve Got to Do Something”

While much of Boston had Patriots’ Day off on April 15, 2013, Boston magazine’s editorial team was working diligently on the May issue. With the printing date rapidly approaching, only some final touches remained. When tragedy struck at the finish line of the Boston Marathon, though, editors quickly realized they needed a new plan.

Reed Baker / Courtesy photo

Matthew Reed Baker, former research and arts editor: It was a beautiful, sunny day, Marathon Monday. It was my wife’s first day back at work from maternity leave, and we met for lunch in Chinatown. On my walk back, I was going to go to the finish line, but I looked at my watch and thought I really should get to work. During that time is when the bombings happened. I was completely unaware until I got back to the office. It was such a weird, shaking moment; I had literally just been a couple of blocks away from it, and everything was sunny and fine, and in that short period of time, walking back to the office, everything changed.

Schwartz / Courtesy photo

Jason Schwartz, former senior editor: I had taken the day off. It was Patriots’ Day, and I wanted to hang out and watch the marathon and drink, as is tradition. I was actually at a party on Comm. Ave., near Mass. Ave. I remember we were all sitting there, and we heard a pop—it sounded like this big, loud pop. And a couple of seconds later was the second pop. And you knew something was wrong. It just wasn’t a sound that you’d hear. I left the party and started to report.

Wolfson / Courtesy photo

John Wolfson, former editor in chief: We just heard these two booms, one after the other. Suddenly we started to get these reports, and then, of course, the mad scramble was to make sure that everyone on our team—we had interns and staffers that were down at the finish line filing reports for the website—was okay, and fortunately, they were.

Ducharme / Courtesy photo

Jamie Ducharme, former intern/Northeastern student: I remember feeling really conflicted, because I was there as a journalist, but I was also a 19-year-old college student, and I couldn’t quite decide how much responsibility I had to try to cover what was happening, or whether I should just focus on getting home and getting to a safe place. I took a few pictures and tried to get as much of the scene as I could, but basically erred on the side of just going home because I was freaked out.

Schwartz: I’ll never forget seeing all the runners stopped at the bridge on Mass. Ave. That’s when I was like, Holy shit. It was just this surreal situation. Eventually, my phone died, and I went back to the office.

Struble / Courtesy photo

Brian Struble, former design director: Really, the first couple of hours, it was just watching the news like everyone else. The editor/magazine part of us didn’t really set in until we knew everyone on staff was safe. Then the journalism DNA in us hit, and we were like, We’ve got to do something.

Wolfson: We were in our final week before we had to ship the magazine to the printer and you know, that’s not something you can move around. So delaying was not really an option here. But we just knew we had to do something on the cover, regardless of the amount of time that was available to us.

Jasnoff / Courtesy photo

Brittany Jasnoff, former managing editor: I do remember the moment when John Wolfson told me that we were going to be scrapping the cover and a feature to do something else. And what that something else was, I don’t think was clear.

Slade / Photo by Craig Lacourt

Rachel Slade, former articles editor: Magazines move slowly—like a cargo ship—and it’s very difficult to turn the thing around, especially when we were going to press so soon. John said something about, you know, “Empty your notebooks!” And I thought, We’re not newspaper people. We don’t have notebooks!

Struble: For the cover, John said, “Well, pitch me some ideas in the morning.” He came out and walked into the open hall where all the editors sat and said, “Everyone, come over to the art department for a minute.” And he just gave a great speech in which he said, “You need to be the magazine that the city deserves.” I thought that was just really powerful. That was my starting point, really, for all the ideas. That line really stuck with me. Honestly, we just needed the day to calm down. Late that night, we kicked around some illustration ideas online.

Hollands / Courtesy photo

Courtney Hollands, former senior lifestyle editor: The original idea was to have notable writers from around Boston write some reflections on the marathon bombings and the marathon.

Struble: I asked the junior people in the art department who were more in tune with social media—even Instagram was a newish thing back then—what’s the symbol? What can we get our hands on to photograph?

Wolfson: At one point they were considering taking finish-line tape and fashioning that into a heart.

Lacey / Courtesy photo

Scott Lacey, former photo editor: I remember deputy art director Liz Noftle first suggested, “Oh, maybe there’s something we could do with shoes.”

Struble: People started making little memorials on the police barricades, putting flowers out, and stuff like that. Some people started tying their shoes to those memorials. It was just like a light bulb went off. It was like, Shoes. That’s it. What can we do with shoes? Let’s do them in the shape of a heart.

Noftle / Courtesy photo

Liz Noftle, former deputy art director: We definitely felt like using the real shoes was what would make it powerful and have that resonance.

Struble: On Tuesday morning, I went in and pitched the idea. I had some illustration examples and was kind of pooh-poohing some of the ideas and saved, really, the only option for last. I was hoping John would go for it. The only issue was the timeline—it was going to be really hard to pull off.

Wolfson: We had three days to pull this all together. We didn’t have enough time to change course later if it didn’t pan out. But it was in that moment that we just decided, We’re doing it. In that moment, I did feel very, very strongly that this was our moment; this was our opportunity to help this city heal and be what this city needed.

It took a village to arrange marathoners’ shoes into the cover’s iconic heart shape. Clockwise from left, assistant Keith Krick, design director Brian Struble, agent Nathalie Cordoba, pup Lola, photographer Mitch Feinberg, and stylist Megan Caponetto. / Styling by Megan Caponetto / Photo by Mitch Feinberg

“The Most Important Thing We’re Ever Going to Work On”

With a plan in place, the entire Boston magazine editorial team began working together on a single mission—sourcing shoes. Staffers canvassed hotels, attended vigils, and reached out to friends of friends of friends. And while the request may at first have seemed odd, they were rarely turned down.

Wolfson: I pulled everybody together, and I said, “This is it. This is probably the most important thing we’re ever going to work on, and everybody here is going to be a part of it.”

Hollands: When something like this happens, it’s good to keep busy. Once our team came up with a brilliant idea, it was like, okay—we all saw the vision.

Struble: I didn’t know how many pairs we were going to get; I thought maybe we were going to get 10 pairs of shoes or something like that. For the first day, we had one pair.

Wolfson: We immediately jumped on all of our social media channels: “Did you run in the marathon? If so, would you be willing to allow us to photograph your sneakers?” Everybody on staff was contacting everyone they knew who ran or who might know someone else who ran.

Baker: I remember connecting with a second cousin of somebody that I went to high school with. I hadn’t even spoken to that friend from high school in ages. But I was like, “You’re Dave’s second cousin? I went to high school with him.”

Schwartz: I remember thinking, There’s no way we’re gonna get enough shoes to do this. Literally, we’re asking people to give us not just their running shoes but, for a lot of people, really meaningful items. We’re asking them to just give them to us and hope we send them back. And not only were we asking them to give us their shoes, but we were also asking them to bring them to us. And people did it.

Wagner / Courtesy photo

Steven Wagner, 2013 marathon runner: I was a sophomore at the time. It was my first year running. There was a message sent to everyone who ran on behalf of Boston College Campus School about the magazine project. We used to have a bunch of bandit runners that would raise something like $200, and by doing that, we could get a bus to the starting line and run without an actual bib. I think because there were so many of us, a good chunk of the shoes came from people who ran it on behalf of the BC Campus School.

Hollands: Everyone had the same question: “Will we get the shoes back?” So we had to put little name slips inside the shoes.

Struble: We printed out flyers for everyone to write their name and address on so we could get the shoes back to them. They had to fill it out twice so we could stuff one in each shoe.

Slowey / Courtesy photo

Kathy Slowey, 2013 marathon runner: Initially, I thought, These are special sneakers. I’m not going to send them. But I did. I put a mailing sticker inside of them so I would know they weren’t just a duplicate of another pair of Asics.

Wolfson: It’s one of those moments in life where something that you would never have imagined 24 hours ago could have been valuable suddenly becomes the most valuable thing you can imagine. Every pair of shoes that someone wore in the Boston Marathon was like this piece of gold—we just were so excited to have it.

Nijensohn / Courtesy photo

Lynda Nijensohn, 2013 marathon runner: I don’t have a complete memory of how I specifically found out about this; I don’t know if it was on Facebook or what. But I thought, Oh, this will be cool. I run in barefoot shoes, and they were pink, so I thought it would be cool to contribute them.

Struble: I was sitting in my office at one point, and the head of HR came up with the editor in chief. I was like, What’s going on here? And they had this box, and they had these shoes in there. They still had dried blood on them. She said, “[These shoes are from] a friend of a friend—an Army Ranger who was at the finish line who saved everyone’s life by going around and putting a tourniquet on everyone.” That was the impetus for the whole inside of the magazine. We decided to photograph individual shoes and tell their stories.

Hollands: I interviewed Nancy Smith, a Dana-Farber charity runner who I actually got in touch with through another friend who was a hairdresser on Newbury Street. I remember it was really powerful because she had just crossed the finish line when the bombings happened. The stories were really harrowing.

Schwartz: It’s hard to overstate what a feeling of togetherness there was in the city at that time.

Slade: It was so intense when people started showing up and telling their stories. I wasn’t trained as a reporter, and to be there for that moment made me really realize the power of what we could do.

Hollands: I just remember doing the interviews at all hours in the office lobby. When people dropped shoes off, you’d try to grab them and bring them into a conference room or just sit in the lobby talking to them. It was emotionally draining; some of the stories were really powerful.

Schwartz: Doing those interviews was extremely affecting. I think the whole city was emotional, but these runners were the people at the center of it. It’s something that stays with you.

Baker: We made sure that everybody we spoke to and everybody’s shoes that we got—that these people actually ran in the marathon. I tend to be a very earnest people person. But in my job as a research editor, which I had done for a long time, I had to always presume the worst in people.

Slade: Scott Lacey was shooting each pair of shoes, and then there was this question of: There was blood on them, and was that the right thing to do to show that? Because I think we wanted the tone of the story to be hopeful, not tragic.

Baker: It was a lot of shoes, a lot of stinky shoes. I remember so well that really brought home the physicality of the marathon. Somehow you felt so much more physically present in what the marathon was that day by smelling the shoes.

Jasnoff: We had this enormous spreadsheet. We were tracking all of the people who dropped off shoes at our office, and we had interns who were logging everybody’s name, address, and phone number. I was just kind of keeping that train running.

Baker: I don’t remember finding one phony. I expected to. I did not find anybody who misrepresented themselves, and normally that would make me nervous, but in this case that made me feel heart-happy, so to speak.

Jasnoff: It was incredibly nerve-racking the whole time—on Monday night of close week to say we’re starting from scratch. But once the shoes started trickling in, I do feel like it started to feel a little bit more tangible and like something we could actually accomplish.

Struble: Wednesday afternoon, the shoes really started coming in. And then Thursday morning, I was literally throwing them in big garbage bags in the back of my car, and they were still coming. But I was nervous right up until Thursday morning.

Photographer Mitch Feinberg poses with the work in progress. / Photo by Mitch Feinberg / Styling by Megan Caponetto

“Building Up the Heart”

With the shoes collected, the next step was delivering them to a photographer who previously had been out of budget for the magazine—and who, at the time, was booked on another gig.

Feinberg / Courtesy photo

Mitch Feinberg, studio photographer: I was on a shoot for another magazine when a call came in to my agent about a project having to do with the bombings for Boston magazine. They said, “Look, we’ve got to shoot it the next day.” The magazine I was working for was very gracious and said we could stop their shoot.

Struble: We had a running list of photographers, and he was always on our list of, like, Ah, it would be great to have him, but we can’t afford him. I mean, he’s shooting in Paris, and he’s got two studios and stuff. Scott Lacey said, “Let’s just try.” So I called, and he said yes immediately.

Feinberg: When you’re a still-life photo-grapher, just about every photograph can be remade at any particular time. But this was one of those occasions where the picture could only be made once. And it was just at that moment for that time to commemorate that incident. It felt both urgent and important.

Struble: The money we could pay wasn’t an issue for him. We maybe paid for his electrical bill that day; it was nothing. We didn’t have any budget anyway because the issue was tapped—the issue was done. We’d already done all the photo shoots and illustrations, so we were starting with zero.

Feinberg: The picture would have been less strong if it was just random color. If the shoes weren’t organized by color, I felt like it might have looked like a cutout—like you just took a picture of a bunch of sneakers and then put a black heart over it. I felt like it needed some kind of intention. And I felt like having the red in the center and going dark felt right.

Struble: We knew we were going to do a heart, but we didn’t know how we were going to lay the shoes down. It started messy, but then, it just felt more respectful to be a little cleaner with everything. That morning of the shoot, Scott said, “What if you organize it by color?” That was the final send-off before I went to the shoot. So we separated all the shoes by color and started laying them out in the heart and it was immediate. The minute you saw it, we only had two rows down, and it was like, This is gonna be great.

Feinberg: I had my stylist, a woman named Megan Caponetto, help arrange and get all the colors together. It ended up being quite big—a couple of meters across and high because it was so many sneakers. My agent and her assistant came; we had a lot of us just filling up the space because it took a long time to do and get it right. Just to arrange them to get that rainbow took a long time. We were all frantically trying to get it done.

Struble: As we kept building up the heart, it just got better and better.

Feinberg: There was a question of what to do with the laces. Do I tie the shoes? Do I not tie the shoes? I felt that having the laces in looked a little like veins and gave it a bit of an artery feeling, and that made the heart feel more human in a way. And it gave it scale. It just seemed better to me. And the barefoot shoes were perfect—it was just what I needed to fit into that nice shape. That was just complete serendipity. I was lucky. By the end of the day, the picture was completely done.

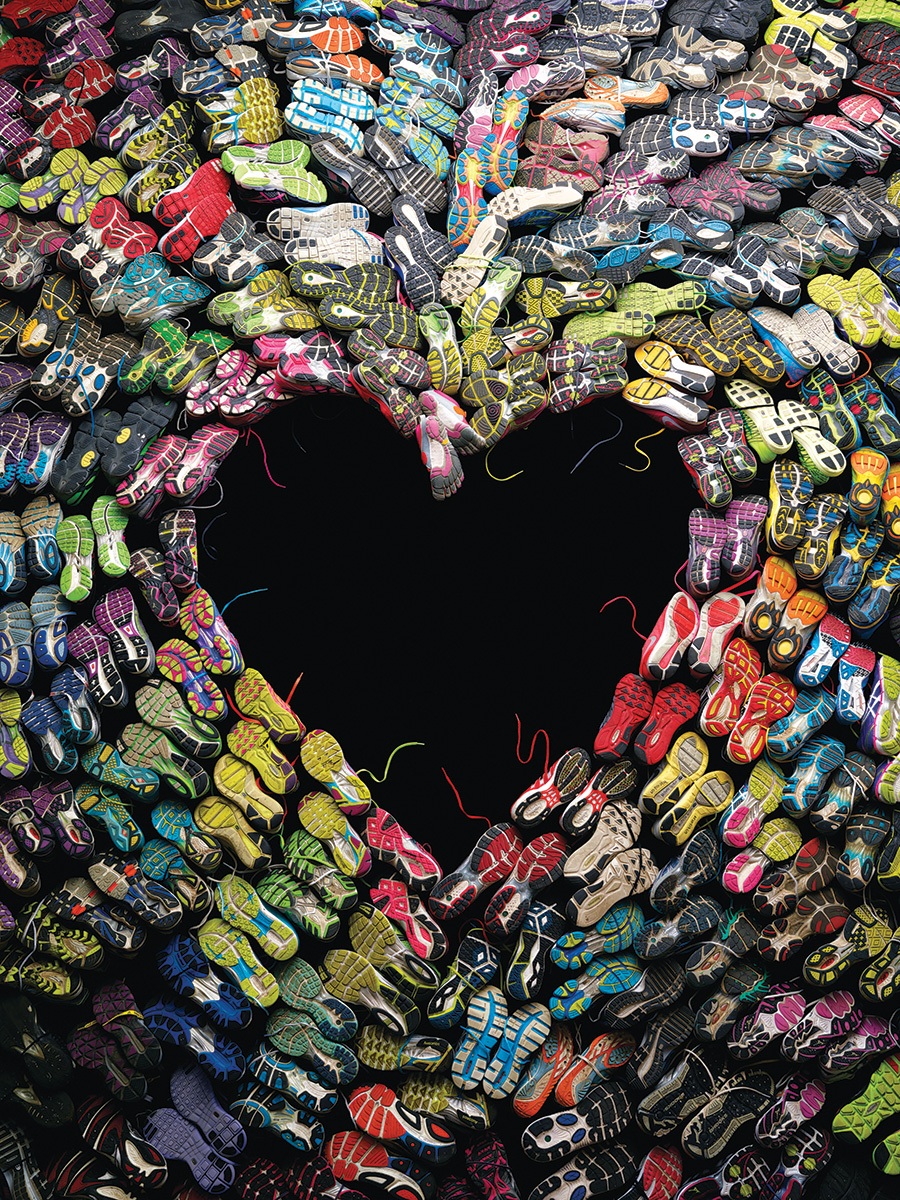

Struble: As far as the back cover, we had ended up with extra time at the shoot. Flipping the shoes over to the other side, that was just a bonus. Mitch said, “Oh, this could be the back cover.” I said, “Yeah, that would be awesome, Dude. But it’s not going to happen. My publisher would never give up that advertising space.”

Wolfson: The back cover is an incredibly valuable advertising space for the magazine—for any magazine. To be clear, magazines were already hurting for revenue at this point. I went to [then Boston magazine president] Rick Waechter, and I said, “We really feel doing this on the back cover will complete the effect. And I’d like for us to not run this advertisement and instead put this on the back.” I felt like it was going to be an argument, but I thought I could probably wear him down.

Waechter / Courtesy photo

Rick Waechter, former Boston magazine president: I said, “There’s no way I’m giving you the back cover. It’s too much money.” And John said, “Well, let me just show it to you.” When I saw it, I said, “Yeah. It’s got to go on the back cover. Let me try to figure it out.” I gave the advertiser about three times the value in other ad spots in order to free up that space. So, of course, it cost me money, but—this is cliché—it wasn’t about the money.

Struble: Driving back to Boston from New York on Friday morning is a personal memory—going 110 miles per hour to make the print deadline. Obviously, the cops had bigger things to deal with. I had I-95 all to myself.

Jasnoff: They locked down the whole city on Friday, and Friday was our final day before we went to the printer, like that was it. We didn’t have any more time. Back then, we didn’t have the remote-work capabilities that we do now, but we managed to do it.

Wolfson: It was just the three of us in the office—Brian, Rick, and myself. Brian had the photos back, and he and I had to work together to lay out the cover, to figure out what the cover lines were going to be, and how we were going to do it. We had settled on “We will finish the race,” which is something that President Barack Obama had said, and I had found very comforting. We were setting that up inside the heart, and Brian was putting that quote on two lines. I vividly remember him saying, “This is the most important line break of my career.”

Jasnoff: I remember at 4:30 p.m. that day getting the proof of the cover from our corporate office in Philly. And I looked at it, and I thought it was amazing. I was so excited about it. But there was one thing that I noticed on it: the “T” in “We Will Finish The Race” was capitalized. And it’s not supposed to be. We don’t capitalize “the” in title case. But I did not say anything about it, because we were about to roll the presses. I knew this was going to be a great cover, so I said, “Let’s just roll with it.”

Wolfson: It was a race to get to the printer—without question. I still remember Brian clicking the “send” button to get it off. We were right up against the deadline.

Photo by Mitch Feinberg / Styling by Megan Caponetto

“A Proud Day”

Nine days after the marathon bombings, Boston magazine shared its cover online ahead of its news-stand release. Almost instantly, the image went viral. It’s still remembered fondly today.

Wolfson: We had decided—this is not something we normally did—but we had said that we were going to tweet out the cover ahead of time. I remember the moment I said to my wife: “All I care about and all I hope is that this cover can mean something in Boston. That it can bring some kind of comfort or some kind of community or some kind of support to the people who live here.” We were all suffering, and we were all afraid and angry.

Schwartz: I remember opening it on my computer and gasping. It literally just took my breath away. It was just like, Wow. They got it.

Wolfson: I got into my car, drove to the office, and by the time I walked in, the cover had been tweeted, and my voicemail inbox was completely stuffed. It’s so rare in life that you get that kind of feedback, especially the kind you’re hoping for—but it’s especially rare in journalism. It was incredibly, incredibly rewarding.

Struble: It was a little weird because I was already onto the next issue. I had a big photo shoot planned because we were featuring all these local athletes from colleges in the area. I was really stressed and focused on this photo shoot the day the cover dropped. I didn’t even fully understand until that afternoon how far it really took off.

Lester / Courtesy photo

Toby Lester, former editorial director: John, in particular, as soon as it went out on social media, he just started getting media requests from people like Anderson Cooper. I don’t remember who else, but it was just a lot of attention.

Baker: For weeks, we were a national magazine because of that cover. We won a National Magazine Award.

Wolfson: I think it was incredibly important to us to recognize that this was an honor for us, but it was not something to celebrate. It was not something to take pleasure in. Martin Richard was the eight-year-old boy who died in the explosion. I have two children, and at the time, they were younger, and I just always kept a vision of him in my mind that entire week.

Schwartz: Whatever it was that was drawing people—in horror, largely—to this story, I think the cover tapped into that in a positive way. And maybe that’s why it resonated so much. I always thought it had something to do with the symbolism of the marathon—this wonderful coming-together event and the shattering of that. But who knows?

Wolfson: To this day, I’m the proudest of this of anything I’ve done in my career.

Hollands: It was definitely a proud day to work at Boston magazine.

Jasnoff: It was a pivotal experience in my career. The lesson that I walked away with was that you can make anything happen, even if you just have three days.

Wolfson: Of all the time I was editor of Boston magazine, the one thing I have framed on the wall is that cover. I’m looking at it right now in our dining room.

Struble: I have the original color proof hanging up in my office.

Feinberg: I was really honored and very happy to have the opportunity to make that photograph. It’s one of the better photographs I’ve made during my career.

Wagner: I still have those shoes; they’re one of those pairs that I still hang on to.

Nijensohn: I remember when I saw the cover, looking for my barefoot shoes and them being there. Those are my shoes right in the center.

Wolfson: Rick immediately did all this work figuring out how to get the cover turned into a poster, working with the One Fund, which had been set up to raise money to support the victims of the bombings. We sold 5,000 posters, and it all went to the fund. I was very proud of what the business side of the magazine did as well.

Feinberg: Because the photograph was so strong and became a symbol, we sold posters, and there were mugs and puzzles and everything else. And everything went to the victims’ fund. We generated a lot of money. I still periodically get requests for prints. I usually sell my prints for thousands of dollars. For this, I’ve been selling them for $1,000 each, depending on the size, and all of that money goes to Boston Children’s Hospital.

Wolfson: To this day, 10 years later, I’ll walk into a coffee shop, and someone will have the poster on their wall or—believe it or not—I’ll even sometimes see a copy of the magazine on a table. And it gives me such a warm feeling to have been a part of that.

First published in the print version of our April 2023 issue.

Art direction by Benjamen Purvis / Photo illustration by Comrade