How I Learned There’s Heroism in Preparedness

Former Boston Marathon executive director Tom Grilk reflects on the lasting lessons of the 2013 bombings.

Portraits in leadership: President Obama and then-BAA head Tom Grilk met after the bombings. / Photo by GM/Current Affairs/Alamy Stock Photo

April 15, 2013, was a gut-wrenching, horrible day, one in which I, as executive director of the Boston Marathon and president of the Boston Athletic Association, had a front-row seat. For all of us in and around Boston and throughout the world, it was a day of shared sorrow, knowing that Martin Richard, Lingzi Lu, and Krystle Campbell had lost their lives to murdering terrorists and that a great many more innocent people had been terribly injured on what is normally a day of celebration and joy—a day that Mayor Thomas Menino often told me was “the best day of the year in Boston.”

April 15, 2013, was a gut-wrenching, horrible day, one in which I, as executive director of the Boston Marathon and president of the Boston Athletic Association, had a front-row seat. For all of us in and around Boston and throughout the world, it was a day of shared sorrow, knowing that Martin Richard, Lingzi Lu, and Krystle Campbell had lost their lives to murdering terrorists and that a great many more innocent people had been terribly injured on what is normally a day of celebration and joy—a day that Mayor Thomas Menino often told me was “the best day of the year in Boston.”

Marathon Monday 2013 was the worst day, but it was also a day when we discovered the best of ourselves. And now, a decade on, it’s still a day we all carry with us. It remains deeply personal, even for those of us who were not injured that day. There are things that I began to learn that day about our city and ourselves, and time has only deepened them.

What stands out most for me are the emotions of the day and how people reacted to them. The responses among spectators, runners, volunteers, and public safety and medical personnel were powerful in those early moments. There was fear, uncertainty, anger, and even bewilderment. But there was no hesitation to act, despite all of that. We learned immediately that Boston was ready to stare into the face of horror that day and to take it on without hesitation—both individual citizens and all of the public safety and medical institutions. And we learned how proud it made so many of us feel to be citizens of Boston.

The emotions gripped us all. For our family, that came immediately when my wife grabbed me at the Copley Plaza Hotel, her face full of fear, saying she didn’t know where our son, Chris, was. His volunteer position had been on Boylston Street next to the Forum restaurant, where the second bomb exploded. I was able to put her at ease, saying that I had seen him and that he was all right. But those few seconds drew me straight into the emotions that gripped thousands in the chaos of the moment. Then, against that background of nerve-wracking uncertainty and anxiety—with no one knowing if there would be more explosions—hundreds of people sprang into action to save others, starting with Boston’s emergency medical technicians.

Within seconds of the explosions on Boylston Street, EMTs raced toward the blasts to save lives. But they couldn’t reach every injured person all at once—there were wounded everywhere, many of them behind crowd-control fences. Without someone to slow or stop the blood flow from their wounds, they might have died. And who rushed in to provide that critical care just seconds after those pressure-cooker bombs went off? Most of them were strangers, ordinary people who fought through smoke and fire to provide lifesaving aid, with zero regard for their own lives. Today, even as we marvel at their courage—after all, the police were telling everyone to get out of the area before more bombs went off—we learn something from why they did it. All of the stories are different, but they all teach us something about where heroes come from and why they do what they do.

The Celtics gave their “Hero Among Us” award to marathoner Robert Wheeler, right, who was honored for his heroics after the Boston Marathon bombings. Here, he hugs Ron Brassard, whose leg had been struck by shrapnel at the finish line. / Photo by Jim Davis/The Boston Globe via Getty Images

Rob Wheeler and Army Colonel Everett Spain combined to be heroes for Ron Brassard. Neither Wheeler nor Spain had ever met Brassard, and they had never met each other. Yet they were thrown together that day.

Wheeler was running his first Boston Marathon that Monday. Starting as a young child he had grown up mostly in temporary housing through the grace of others, not having a permanent home. Still, he was grateful to the state for the support that he received. He would sometimes find himself praying “to find a purpose,” he said. He prayed, “asking to be put to use, to do something good.” The tragedy of that day gave him the opportunity.

Turning back across the finish line that he’d just crossed, Wheeler quickly found Brassard, with blood gushing from a severed artery in his lower left leg. Wheeler took off his race shirt and used it as a makeshift bandage to stem the bleeding. It wasn’t perfect, but it helped. It bought Brassard a few more minutes. More help was needed, and there were not yet EMTs on the scene outside the Sugar Heaven store on Boylston Street, just yards from the finish line.

Just then, Spain appeared. He had also just finished the race, guiding a visually impaired runner. A decorated combat veteran, Spain also doubled back across the finish line to do, as he recalled, “what soldiers do”: help those who needed it. Coming upon Wheeler and Brassard, the battlefield veteran knew what was needed next. He used his own race shirt as a tourniquet, setting it in place as Wheeler twisted it down tightly above the wound on Ron’s calf. The combination of Wheeler’s bandage and Spain’s tourniquet bought just enough time for the EMTs to arrive and get Brassard to the medical tent and a waiting ambulance. He survived.

What I am drawn to as a learning tool is not so much what they did but why they did it. Why risk their own safety for someone else’s? And for them, the answer to that had a lot to do with the purpose that they had either sought or had found in their own lives.

It was a moment when Wheeler found his purpose—a moment when he could “do something good.” Spain was also able to express his purpose as a soldier, as the two of them combined their efforts to help save Brassard’s life. They were individual citizen heroes, stepping forward to take the lead when it was needed. Without them, and so many others like them who chose to act to face down the terror that day, many of the injured might have suffered far more serious or even tragic results while waiting for the EMTs to reach them. Those citizen heroes on the sidewalk accounted for a large percentage of the initial, on-the-sidewalk measures that sustained the wounded while awaiting the EMTs.

The Boston Marathon has a long history of people aiding others, whether they are runners helping other runners or spectators coming out to the same spot on the course year after year, generation after generation, to cheer and bring refreshments to runners. In so many ways, it’s the ordinary people who make the most extraordinary differences.

That spirit also came out in small ways after the bombings. One of the most touching for me was marathon volunteers such as John Studley and Ron Kramer showing empathy that will last a lifetime for some. When runners who had been stopped by the bombs came later to collect their medals, they were told to step across a small model of the blue-and-gold marathon finish line that the volunteers had put down. They were then told, “You finished,” with their medals placed around their necks. Tears and smiles came out in equal measure.

While these individual actions were vital, we were also deeply fortunate to have had plans and a structure already in place to move the injured from where they lay wounded to the medical tent, then to an ambulance, and then to a hospital that was ready to treat them. Before we were “Boston Strong,” we were “Boston Prepared.” Boston police and fire and emergency medical services, along with state police and all six Level 1 Trauma Center hospitals within a few miles of the finish line, had been planning and rehearsing for a cataclysmic event since 9/11, long before April 2013. Boston was prepared for the terror of that day.

On April 15, 2013, police officers reacted to the second explosion, as 78-year-old US marathon runner Bill Iffrig reeled from the first one. / Photo by John Tlumacki/The Boston Globe via Getty Images

All of that planning worked. Ambulances were summoned immediately, such that on the day of the bombings when there were 16 ambulances staged at the marathon medical tent, another 73 ambulances were brought online in minutes. The 30 most critically injured victims were transported to hospitals within 18 minutes of the explosions, and all seriously injured patients were transported to area hospitals within 50 minutes. Victims were spread across Boston Medical Center, Brigham and Women’s, Tufts Medical Center, Mass General, Boston Children’s, Beth Israel Deaconess, Carney, Faulkner, and St. Elizabeth’s.

The lesson for me and for anyone in all this was that there is heroism in preparedness, in being ready for anything. The phrase “being ready” doesn’t sound very exciting. I never connected planning with heroism. But James Hooley, chief of Boston’s Emergency Medical Services, was right when he said that “planning, training, exercising, sometimes it gets a little boring, repetitious, until you see what happens in the real world.” And in the “real world” of Patriots’ Day 2013, all of that planning, integrated across so many organizations, was decisive in saving lives in the wake of the bombings. It made us strong. And in the same way that “we” sometimes talk about how “we” did when our sports teams win, there’s a lot to learn from how “we” did in being ready for terror when it came.

The horror and the heroism that we all saw that Patriots’ Day flashed around the world. The images were often grim and heart-rending. But many photos were also uplifting, showing public safety and citizen heroes braving deadly danger to take the lead and save lives—even at the possible risk of their own.

The horror and the heroism: Jimmy Plourde carrying Victoria McGrath. / Photo by David L. Ryan/The Boston Globe via Getty Images

One of those images showed Boston firefighter Jimmy Plourde carrying Northeastern student Victoria McGrath in his arms. He scooped her up from the sidewalk, where a bomb had shattered nerves in her lower left leg, to take her to EMTs who could get her into an ambulance. As he helped her and others that day, he was struck by how many other ordinary citizens were doing the same kind of thing. In his mind, he connected what they were doing to the day: Patriots’ Day. “On that day,” he later said, “they decided to take a stand, to say ‘Hey, you know what, I’m going to make a difference. I’m going to help save someone’s life today.’ In that regard, they became true patriots that day.”

The power of those images and all they represented hit home for me many months later when I found myself being interviewed on 60 Minutes by Anderson Cooper in 2014. He didn’t want to know more about what had happened the year before. He just wanted to know if Boston was ready to carry on for the next marathon. Could we come back? That said to me that the rest of the country was wondering the same thing, or else 60 Minutes wouldn’t be asking.

My response was simple: “The race will go forward as what it always has been…and will be seen as a response to terror, as a statement of resilience.” That was politer than the answer in my head, which was, Damn straight, we’ll be ready. If there was anything we had all learned from Patriots’ Day 2013, it was that Boston is ready for anything, and people everywhere knew it.

Still, the most enduring lesson from that fateful day for me—and, I suspect, for many others, too—is how proud we can be to live in Boston. Three days following the bombings, President Barack Obama came to Boston to join Menino and Governor Deval Patrick to lead an interfaith service at the Cathedral of the Holy Cross in the South End. The president spoke movingly, capturing first the horror of the attack. “On Monday morning, the sun rose over Boston,” he said. “It was a beautiful day to be in Boston…. And then, in an instant, the day’s beauty was shattered. A celebration became a tragedy.”

President Barack Obama at the Cathedral of the Holy Cross on April 18, 2013. / Photo by Spencer Platt/Getty Images

The president then went on to recall the words of the poet E. B. White, saying that “Boston is the perfect state of grace” and to predict the resilience that Boston would display in the days, months, and years ahead. He said that the people of Boston would “finish the race…because of who we are.” Following the service in the Cathedral, the president went next door to the gymnasium at Cathedral High School. In the Cathedral gym, we had gathered a number of the BAA’s volunteers from the marathon, some donning the yellow jackets worn by most of our volunteers and some wearing the white jackets of the medical volunteers. The volunteers were arrayed in a broad semicircle around the perimeter of the gym. The president stopped to speak with each of them individually. Many of them had performed heroically on Monday amid the chaos and horror of the bombings.

At the end, Patrick brought the president over to me. Obama had very kind words for me, though, in the emotion of that moment, I couldn’t remember, then or now, what they were. But I can remember precisely what I said to him: “Mr. President, it is the privilege of a lifetime to lead this organization. And all the people you just met, with the yellow and white volunteer jackets, we had to issue new jackets to some of them this morning because the ones they wore on Monday are too bloody.”

It was a moment that is still challenging for me to recount without getting a hitch in my voice. I was so humbled to be associated with all of these people and all of the others who displayed the leadership that saved lives as the world watched. As a learning tool, it was a moment that made me very proud to be from Boston. It still does.

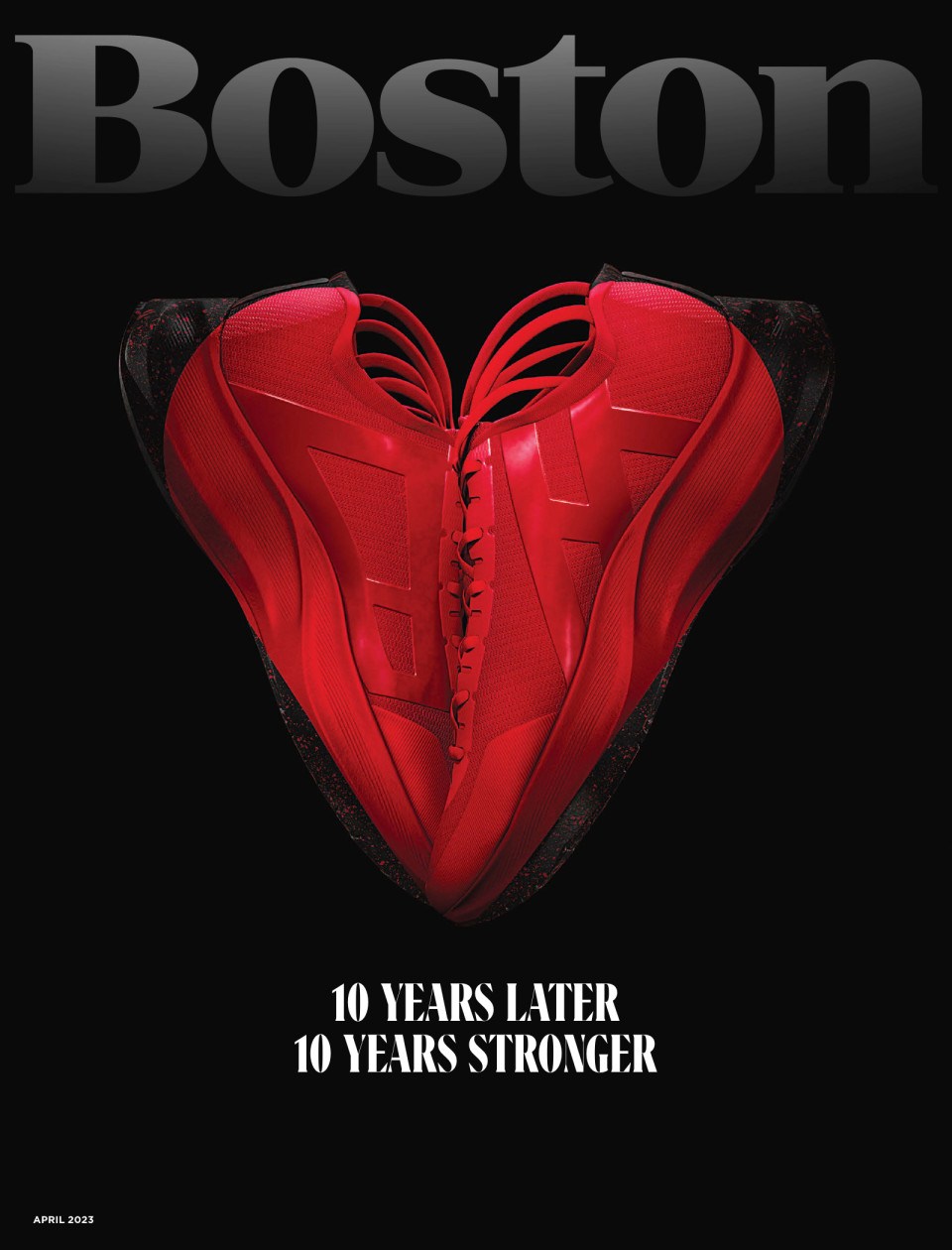

First published in the print edition of the April 2023 issue with the headline “Lessons Learned: The Race Organizers.”