It’s Time to Get to Know Sam Slater

The Boston-area developer, Seattle sports team owner, and Hollywood film producer is a man on a mission: to make the company bearing his family’s name the most successful it can be—and make a name for himself in the process. But first, there are a few things he wants to clear up.

Sam Slater. / Photo by Ken Richardson

The first thing I notice as I make my way through the minimalist Boston headquarters of Slater Family Holdings are the cupcakes. There are two trays of them—beautifully adorned and perfectly bite-size—sitting on the sleek countertops in the empty office kitchenette. Somewhere in the background, I can hear two staffers discussing their origin: the man I am here to see, Sam Slater—the de facto CEO of his family’s billion-dollar empire—brought the cupcakes.

I take out my phone, do a quick Google search, and then look at the date on my calendar. It’s Slater’s birthday. He made no mention of it when we scheduled the interview.

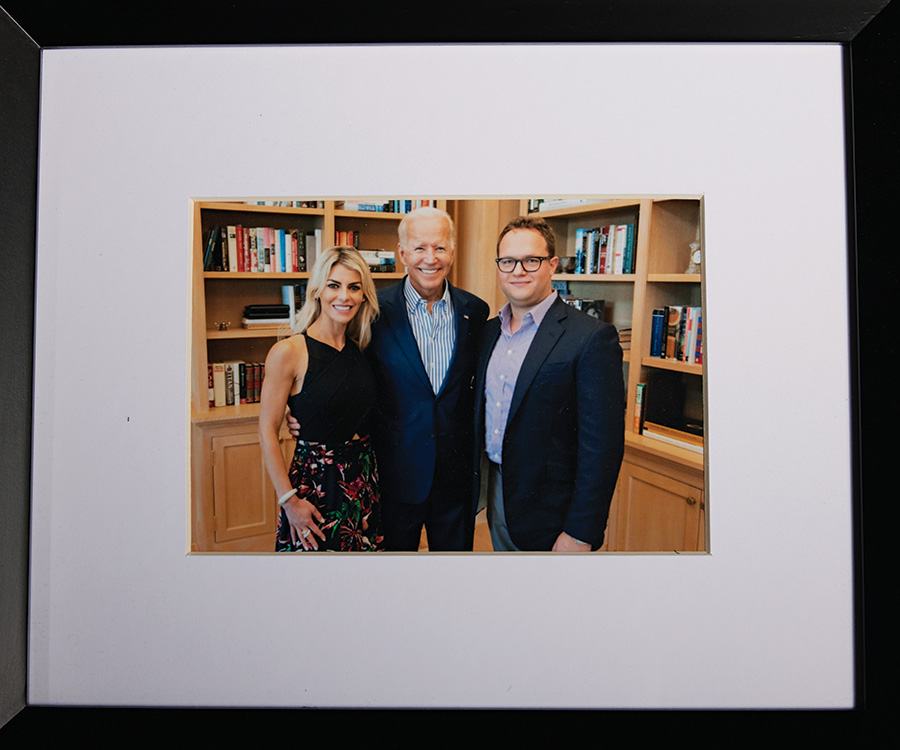

After I am ushered into his expansive office, adorned with photos of dignitaries and famous friends and movie posters from films he’s produced, I address the elephant in the room. “Happy birthday…?” I say with a hint of trepidation.

Slater confirms that it is indeed his birthday. He has no big celebrations planned in his busy schedule, though he admits throwing big parties is kind of his thing. In fact, he is in the midst of planning an extravagant birthday bash on the Cape for his wife, which includes flying pop star Gavin DeGraw in to perform. Yet his own birthday celebration is almost an afterthought. As we chat, he’s busy searching for a restaurant in town that has chicken fingers on the menu, a must for his two young children, in case he has time to go out for a celebratory meal with his family. In the end, he winds up just having dinner at home. “I’m here working on my birthday,” he says with a shrug.

Photo by Ken Richardson

As it turns out, Slater was telegraphing something he wants me and, by extension, all Bostonians to know: He is not just some scion who inherited the hugely successful real estate and investment company that his self-made grandfather built, and he doesn’t just come into the office to play executive while spending his family’s money on poorly thought-out purchases for eye-popping sums. “I kind of love being discounted,” he says. “I love the challenge of having something to prove. I need that. Maybe they think I don’t know what I’m doing, or I’m too young, or I’m not hardworking, or I’m not serious enough.”

It’s not too difficult to see why people might get that idea. After all, the first time he really made a splash in the media—brief as it was—was when he bought Playboy’s “Big Bunny” private plane for his family’s real estate company last year. And he has taken some swings far outside the traditional stomping grounds of the family business: He became an owner of the Seattle Kraken, an NHL team, and launched a Hollywood production company with entrepreneur and TV personality Bethenny Frankel’s now-fiancé, Paul Bernon. To an outside observer, his newer business dealings could read like the textbook stages in the life cycle of a wealthy party boy in the process of squandering a family’s real estate fortune. It probably doesn’t help that he has something of a boyish energy that makes him seem younger than his 39 years.

Slater is self-aware enough to grasp the optics. “When you’re venturing into something that can be perceived to be glitzy, like film or television, or a guy in his mid-thirties going into sports,” he says, “the initial knee-jerk reaction for most people is that maybe it’s ego-driven.” Despite what it might look like at first glance, Slater assures me, everything he does is motivated by a strong investment thesis and is never a function of excess or ego.

Slater and wife Jessica at the 2018 Gotham Awards in New York City. / Photo by Lexie Moreland/WWD/Penske Media via Getty Images

The reality, though, is that a quick glimpse is all most people can get of Slater. Despite being among the most wealthy, well-connected people in this city, with contacts that range from movie star Regina Hall to President Joe Biden, few people know much about him. Despite his ranking on Boston’s 150 Most Influential Bostonians of 2023, Slater doesn’t appear in the media often, and he’s certainly never been the subject of a lengthy magazine feature.

That is all about to change, and for reasons far beyond this profile. Soon, in fact, people from coast to coast will know the Slater name. His production company is currently developing what he calls a Succession-style scripted television show focused on a successful family building a real estate dynasty. Sound familiar? If not, the name of the lead character, “Samantha Slater,” will leave no doubt of the family that inspired the show. For the first time ever, it seems as though Slater now wants people to know who he is. Sort of.

When Boston first reached out to him for the story, Slater enthusiastically offered plenty of access and time. But during the reporting process, he occasionally disappeared and studiously revealed only one side of himself—Slater, the workaholic—which is certainly authentic but not the full sum of his many parts. The TV show he’s developing doesn’t seem like it will reveal much more: The characters may bear his family name and background, but from what little he is allowed to tell me, it seems that the story line will be largely fictional. He won’t reveal any specific family drama that makes his show Succession-like. It seems that Slater wants to be known, but because he doesn’t want to be perceived the wrong way, a lot of the time, he doesn’t let people see much of him at all.

Sam Slater oversees the real estate arm of Slater Family Holdings. / Photo by Ken Richardson

The image that Slater seems so intent on avoiding could easily once have been his own. As a student at George Washington University in Washington, DC, he made a name for himself running the ultimate playboy business—a successful party-throwing company. As he neared graduation, Slater had the option of going into the business post-college, as some of his friends decided to make a career of it. Then life, or rather death, intervened.

It was a February day in 2006 when the phone rang in Slater’s DC apartment: his grandfather, Alvin Slater—the family patriarch, a man who came from a humble immigrant family in Lowell, built a successful company, and amassed a family fortune, who still ran the family business at age 86—had been at home reading when he suffered a stroke and died.

Slater packed his bag and scrambled to the airport, where he bought a ticket on the next US Airways Shuttle to Boston. Several days later, he said his final goodbyes to his grandfather inside the Levine Chapels funeral home, a brick Greek Revival building in Brookline. During the days that followed, Slater sat shiva—the Jewish term for a seven-day, post-funeral mourning period—by his grandmother’s side at her home at the Four Seasons on Boston Common.

The head of the family was now gone, but his business needed to live on. Slater’s father, Ken, stepped up to lead the company, and in that moment, the once-latent question of whether Sam Slater would chart his own professional path or enlist in the ranks of the family empire was staring him in the face. “There had always been a person overseeing everything, whether you liked it or not, and suddenly that person had left,” says Slater’s dad, Ken, of his own father, Alvin. “There was sort of a sinking-in of responsibility.”

Slater’s younger sister, Jacqueline Slater Whitten, vividly remembers that time as a crossroads for her brother. “It was a huge moment for our family and a big moment for Sam. It was a wake-up call for him: This is coming down the pike. If you want this—this path—this is yours to engage with,” Whitten says, adding that, at the time, she planned on pursuing a career in public policy and only joined the family business years later.

The Slaters with radio and television personality Andy Cohen in 2017. / Photo by Paul Marotta/Getty Images for The Lenny Zakim Fund

Sam Slater chose to stick with his family. “There was an opportunity to go in that direction, if that’s what I felt was the right move,” he says. “It felt like a natural step.” That also meant that he had something to prove, especially considering that age-old adage about generational wealth: the first generation makes it, the second spends it, and the third destroys it.

Slater dove into real estate, starting at the bottom. He worked as a laborer, doing commercial fit-outs, and then showed properties as a rental agent. Along the way, he mastered the art of connecting people and managing relationships—an area where he had always shown an aptitude—as well as the ins and outs of real estate. Much of it was grueling, he admits, though he says it was all part of his journey to the top.

Today, Slater is the managing partner of Tremont Asset Management, the real estate arm of Slater Family Holdings, which has a portfolio of more than 3,500 Class A apartments (the top quality classification), office properties, and agricultural holdings in a dozen states and Canada. The company focuses on three primary markets: Houston, Quebec, and Massachusetts, where many of its properties are in Quincy, Brookline, and Boston. The Slaters’ bread and butter is so-called commodity housing—student, market-rate, and senior residential properties.

Slater received the 2017 Hope Award at the Ellie Fund’s 5 for Ellie Spring Fashion Show at the Fairmont Copley Plaza in 2017. / Photo by Paul Marotta/Getty Images for Ellie Fund & Slater Foundation)

In Quincy, the Slaters are currently developing two separate residential towers. And in Boston, Slater is engaged in a high-profile redevelopment process of converting a five-story turn-of-the-century apartment building—an existing Slater Family Holdings property—across the street from the Museum of Fine Arts and the Emerald Necklace into a 157-unit residential tower that balances housing needs with the historical nature of the neighborhood.

On a sweltering 90-degree day in Boston this summer, I am standing next to Slater on the blacktop roof of a brick office building along the harbor’s edge that he is thinking of buying. Along with us is his go-to entourage: a young real estate analyst, a.k.a. the runner of numbers, and his general counsel, a sound voice of reason and legal advice wearing Karl Lagerfeld hiking boots. “It’s one of the best views in town,” says Slater, wearing his unofficial uniform of a dark Rag & Bone polo, tapered blue jeans, tan loafers, and a Rolex watch. He points out landmarks, the panoramic view of Boston Harbor, and planes taking off from Logan in the distance and starts thinking—out loud—of ways to maximize the space and deal with the zoning restrictions for that area, which he knows by heart. He’s so excited by the possibilities that one of our tour guides tells him to move a few feet back from the edge of the roof.

Slater is undaunted by the blistering heat of the afternoon or the loud grindings from the rooftop machinery that resemble the sounds of a dying animal. Remarkably, he is equally undaunted by Mayor Michelle Wu’s pricey climate-change-related building restrictions and affordable-housing requirements that have so many developers upset and refusing to invest in Boston. “We’re embracing affordable housing and incorporating it into [our projects],” says Slater, adding that he believes Wu is “ultimately trying to help people.”

From left: Charles Daniels, Josh Zakim, Duron Harmon, Jason Kennedy and Slater at the 10th Annual Lenny Zakim Fund Casino Night at Four Seasons Hotel in 2019. / Photo by Paul Marotta/Getty Images for Lenny Zakim Fund

Before we leave the roof, Slater checks his enthusiasm—instructing his entourage to run the numbers again while saying they will make an informed decision on the property. If it does pass muster and the deal goes through, it would be just another notch in Slater’s real estate belt. Since joining the family business, he has personally led more than $2.7 billion in completed deals. Far from squandering his family’s legacy—let alone making an impulsive decision in a rush of enthusiasm on a hot roof—he’s instead embraced a conservative, long-term approach to investing and, over a decade, grown the real estate division five-fold. “Sam doesn’t do anything halfway,” says former city councilor and executive director of the nonprofit Housing Forward-MA Josh Zakim, Slater’s friend of nearly 20 years. “He’s not a dabbler. He does research, works hard, builds relationships, and more often than not, is successful.”

As Slater stewards the company, his grandfather Alvin is never far from his mind. “Family is the why of what I do,” he tells me. Still, protecting the family legacy under his watch was never enough for Slater. He wanted to make a name for himself, branching out into more public—and definitely more fun—terrain.

Slater has expanded the family company into sports—he owns the Seattle Kraken—and entertainment. / Photo by Ken Richardson

One morning in August 2022, Slater attended a secret meeting in a private airplane hangar at Van Nuys Airport in southern California to check out a possible investment. He climbed the steps of a private plane, walked through the door—the interior side of which was embossed with the signature Playboy Bunny logo—and noted the details inside: herringbone carpets, custom-dyed cognac leather seats, crocodile-embossed wallcoverings, and a top-of-the-line sound-and-entertainment system.

Slater had been in the market for a company jet, but this was a deal like none other. The aircraft was in mint condition after the publicly traded Playboy company poured a fortune into its renovation—resurrecting the name Big Bunny from Hugh Hefner’s original jet and giving it its own Instagram handle—as part of a high-profile campaign to market the dawn of a new era at Playboy. Just a year later, however, the company was financially stressed, and the plane represented a significant chunk of its assets. It had to go.

Slater recognized that the plane’s rare pedigree made it a unique asset with the prospect for some serious chartering traffic on the days it was not in use for the family company—meaning it had the potential to function as its own money-making business. There is a certain irony to the fact that a man who doesn’t want people to see him as a party boy would consider snapping up the physical embodiment of a young playboy’s pleasure palace at 35,000 feet. Still, it checked all the boxes for a good investment, Slater says, so he bought it.

Slater wasn’t thrilled with the obvious narrative depicted in the media coverage that followed: The heir to a real estate fortune buys Playboy’s private jet for status. (Never mind that he promptly removed the Playboy logo from the plane’s tail and replaced it with his grandmother’s initials, more in keeping with a total mensch rather than a playboy.)

This type of intrinsic misunderstanding, Slater believes, has plagued him throughout all of his latest ventures, including wading into the world of film production, where he felt discounted as simply a “money guy” with a fleeting interest in film. Slater’s solution was to find a good partner in fellow real estate mogul Paul Bernon—who, unlike Sam, did have a background in movies, including having gone to film school—and learn every part of the movie business from the ground up.

Paul Bernon and Slater discuss Drinking Buddies at the 2013 Nantucket Film Festival. / Photo by Andrew H. Walker/Getty Images for The Nantucket Film Festival

The partners threw themselves into their first film, Drinking Buddies, a largely improvised small-budget picture directed by Joe Swanberg and starring Olivia Wilde that was well received. Since its inception in 2012, their production company, Burn Later (an amalgamation of its founders’ names), has produced more than 30 feature films and shows, many of which are relationship-driven with lean operating budgets. Slater often secures bigger-named talent for less money by offering them a rare chance to work in genres outside of their usual typecasting. The company currently has somewhere between seven and 10 projects at various stages of development, including the TV show based on Slater’s family and an upcoming Max series about Heidi Fleiss, the infamous “Hollywood Madam.” (At presstime, these projects were on pause due to writers’ and actors’ strikes.)

Slater had a similar playbook when he entered the professional hockey business as someone who was a casual fan with no background in sports: find experienced ownership partners from whom he could learn the process. What looked like an ego project, Slater says, is fundamentally a real estate opportunity, considering that a sports arena is a central real estate asset in any city and one that he believes the Slaters needed in their growing portfolio. Purchasing a team was also far more than that because, in today’s world, sports aren’t simply sports: They include merchandise, food and beverage, live entertainment, media rights, and legal gambling. Seattle fans have rallied around the return of a hockey club (season tickets sold out for the inaugural 2021 to 2022 season) in the gleaming new Climate Pledge Arena. In its second season, Slater’s Kraken team made it to the second round of the playoffs before being eliminated by the Dallas Stars.

Slater has also gotten involved in politics. / Photo by Ken Richardson

Even President Joe Biden’s nomination of Slater (still pending confirmation) to be the director of the Metropolitan Washington Airports Authority defies common assumptions about these kinds of gigs and how you get them. Yes, those appointments are often sought by young, wealthy heirs in need of a respectable title. But, no, Slater didn’t get the appointment just by writing checks to finance Biden’s campaign from afar. Rather, he earned it on Biden’s campaign trail.

Just a couple of years earlier, on January 29, 2020, Slater found himself trudging up the stairs of a dust-beaten red, white, and blue campaign bus in western Iowa. Five days into the nine-day final sprint leading up to the Iowa Caucuses, Slater felt an aching weariness well beyond his then-35-years and wondered if he had the stamina to keep up with the surprisingly energetic then-77-year-old Biden on what proved to be a losing battle in Iowa. He stuck it out on the cramped bus, getting to know the “real” Joe Biden, Slater says, and working on the campaign finances from the ground up. “I never wanted to be that person who came into some wealth and just decided that was it,” Slater says.

That’s not an uncommon sentiment in the era of the nepo-baby hashtag (short for nepotism baby): Everyone who’s had a leg up in life, these days at least, feels a need to defend their success. Slater is no exception. At least, though, he seems aware of the fortunate place from which he started and is determined to silence any doubters by putting in the work. “I like to think that if I didn’t have a reasonable starting point, that I would have it within me to channel some of Alvin J. Slater,” he says of his grandfather, who didn’t have to battle the same assumptions that Slater does.

Left to right, from the 2016 Sundance Film Festival: (top) Musician Tegan Quin, producer David Bernon, musician Sara Quin, actor Ben Schwartz, producer Mel Eslyn, Vincent Piazza, and actors Natasha Lyonne, Clea DuVall, and Melanie Lynskey; (bottom row) producer Paul Bernon, actor Jason Ritter, and producer Sam Slater. / Photo by George Pimentel/Getty Images for Sundance Film Festival

Slater’s drive to be seen as a hard worker often makes it difficult to see past that part of him and into the heart of the real Sam Slater. His close friends, professional contacts, and family describe him as “magnetic,” “very social,” “personable,” and “fun”—an extrovert with a big personality who can throw an amazing party. So much of the man they describe seems to also bleed into his professional success and his ability to make connections in film, professional sports, real estate, and politics. His ability to forge relationships seems an asset in any context. And yet, it’s not a side of him that he showcases to me.

To see a fuller picture of the Slater that his friends describe would require the source of his kinetic energy—other people—and a room full of them, not just one probing writer. Though he shared many details of his loaded and impressive social and professional calendar over the course of two months—parties, dinners, family time, and major events like the NHL Draft—he doesn’t invite me to tag along on any of them, despite my frequent requests to do so, and I never get to experience this side of Slater firsthand.

He admits he loves to throw a party, and there are rare glimmers of his more extroverted persona off the record and whenever he talks about something brand-new—he mentions he’s investing in professional pickleball and that he may also have another hockey-team acquisition in the works, though it’s too soon to share any details. But most of the time, I watched Slater work overtime to put forth a certain image.

Toward the end of our time together, I asked him if he really cares what people think of him.

“A lot of people like to say they don’t care what people think of them,” he replies without hesitation. “But I think that’s generally a lie. I do care what people think of me. I think it’s a good thing to care what people think of me to an extent that doesn’t inform all of my decisions in life or in business.”

“I do care what people think of me,” Slater says. “I think it’s a good thing to care what people think of me to an extent that doesn’t inform all of my decisions.”

There will soon be far more opportunities for people to form opinions about Slater. This is the first lengthy magazine story about him, but surely just the beginning of his dance with the media. And through our time together, Slater, I think, began to realize the Catch-22 of higher-profile success and the potential for the TV show about him and his family to spark even more misconceptions.

I tell Slater that balancing all of his interests and quieting the noise may be harder than ever in the months to come if the TV show takes off. In other words: I won’t be the last reporter peppering him with questions.

“I know,” he says as if mentally preparing for it. “I can’t really hide.”

Gabriella Gage is a writer from Somerville, Massachusetts. Her last story for Boston was “The New Race to Rule the Automile” in November 2022.

A version of this story was first published in the September 2023’s print issue with the headline, “Desperately Seeking Slater.”