The Karen Read Case in Canton: The Killing That Tore a Town Apart

Did a successful South Shore woman really kill her police officer boyfriend? Or, as she claims, did a slew of dirty cops frame her? Inside the simmering tabloid drama dividing this tight-knit Massachusetts suburb.

Illustration by Jonathan Bartlett

Snow had just started to fall as John O’Keefe and Karen Read stepped into the Waterfall Bar & Grille on Washington Street, Canton’s main drag, on a Friday night in late January 2022. At around 11 p.m., it was the couple’s second stop of the night after visiting another popular local pub.

- How the Karen Read Case Turned a Neighborhood Bar Into a True Crime Landmark

- The Betrayal of Sandra Birchmore

- “Free Karen Read” Blogger Turtleboy Will Not Go Quietly

- Remembering the Real Victim in the Karen Read Case, My Friend John O’Keefe

- The Karen Read Story Continues: Judge Keeps ‘Off the Record’ Interview Confidential

O’Keefe, a burly, brown-haired Boston Police Department officer, had been living in Canton since 2014, raising his niece and nephew after his sister died of a brain tumor and her husband succumbed to a heart attack two months later. (The kids affectionately called their “funcle” by the nickname JJ.) For the past two years, he had dated Read, an equity analyst and adjunct professor at Bentley University who lived in Mansfield but spent much of her time at O’Keefe’s helping with the kids.

Inside the bar, O’Keefe spotted friends sitting at a high-top near the band and he and Read walked over to join them. At the table sat O’Keefe’s neighbor, Chris Albert, town selectman; his brother, Brian Albert—also a BPD officer who leads the Fugitive Apprehension Team and was featured on TNT’s Boston’s Finest—and Brian’s sister-in-law, Jennifer McCabe. All had been raised in Canton, a middle-class town of some 24,000 people located about 20 miles south of Boston, where families’ lives and social calendars are often dictated by high school and weekend sports.

That night, as the storm rolled into town, parents in the bar had a pretty good hunch they’d get a hall pass from the typical Saturday grind of shuttling kids to sporting events. As the band played, the mood was festive and upbeat. O’Keefe downed beers while Read drank vodka sodas—lots of them.

When the clock ticked to midnight, it was nearly last call. The night wasn’t over, though. Brian Albert announced he was headed home to have a beer with his son for his birthday and invited the group to join. O’Keefe wanted to keep the party going. Read—tired, buzzed, and hungry—was less sure but agreed to at least give him a ride. On the way out, O’Keefe grabbed a half-full cocktail glass off the table, took a slug, and carried the rest of the drink out the door with him.

The couple walked over to Read’s black Lexus SUV, leaving foot tracks in the white dusting of snow, and climbed inside. Read sat behind the wheel, and O’Keefe plugged the address—34 Fairview Road—into Waze before they drove off. When they arrived at Albert’s home, O’Keefe stepped out of the car. Read, though, decided to leave.

Several hours later, around 4:30 a.m., Read says she woke up alone—in the same clothes from the evening before—on the couch at O’Keefe’s house. From a living room window, she could see the nor’easter bearing down hard. His niece was asleep upstairs, and his nephew was at a sleepover, but O’Keefe was nowhere to be found.

Read says she thought to call McCabe to ask if she’d seen O’Keefe. Read didn’t have her number but knew that O’Keefe’s niece, who was close friends with McCabe’s daughter, probably did. In a panic, Read woke her up and had her dial McCabe, who said she had no idea where O’Keefe was either. McCabe hung up and called Chris Albert’s wife, Julie—who lived just a few doors down from O’Keefe—to ask if he had passed out at their house. Meanwhile, Read called O’Keefe’s lifelong friend Kerry Roberts, who also lives in Canton. Neither woman had seen or heard from O’Keefe. Where was he? Read says she wondered.

Within an hour, Read, McCabe, and Roberts met up at McCabe’s home, and after returning briefly to O’Keefe’s house, piled into Roberts’s car to look for O’Keefe. In the back seat, Read screamed about her boyfriend being missing as the women drove through the pre-dawn streets of Canton, snow swirling and dancing in the car’s headlights. On the dash, the temperature read 18 degrees Fahrenheit.

34 Fairview Road in Canton, MA on February 2, 2022. / Photo by Craig F. Walker/The Boston Globe via Getty Images)

As they approached the house where Read had last seen her boyfriend, she shouted that she spotted him and scrambled out of the car. It was pitch-black outside, but on the left side of the property at 34 Fairview, she saw O’Keefe’s body lying covered in snow. Read raced toward him, dropped to her knees beside him, and frantically cleared the snow off his torso. Then she lifted both their shirts and laid on top of him, trying to warm his ice-cold body.

Roberts, who had run over to O’Keefe’s body, cleared the snow off his face. Read began giving her boyfriend mouth-to-mouth CPR while Roberts administered chest compressions. Blood ringed his nose and mouth, and his right eye was blackened and swollen. O’Keefe’s baseball hat and one of his black Nike sneakers were missing. McCabe rushed over with blankets from the vehicle to warm O’Keefe and dialed 911 at 6:04 a.m.

As they waited for the ambulance, Read repeatedly cried out McCabe’s and Roberts’s names over and over, her boyfriend’s blood smeared on her face. Soon the police arrived, followed by an ambulance that rushed O’Keefe to Good Samaritan Medical Center in Brockton. Doctors pronounced him dead at 7:50 a.m.

Detectives began investigating, and within days, Read was charged with manslaughter on suspicion of hitting O’Keefe with her Lexus. But that wasn’t the end of the story—far from it. A year later, the court case would blow up on local news sites and become the focus of conspiracy theories that ignited protests, ruined reputations, ended friendships, and divided the community of Canton, shredding the social fabric of the tight-knit suburban town.

Read being arraigned on second-degree murder charges in the killing of her boyfriend, BPD officer John O’Keefe. / Photo by John Tlumacki/The Boston Globe via Getty Images

For three days after finding O’Keefe dying in the snow, Read lay curled up on her parents’ couch in Dighton, shocked and confused. What had happened to John? she kept asking herself. She missed him terribly, Read says, and couldn’t believe he was gone. She called her doctor and asked for medication to help her sleep. She had also located an attorney, David Yannetti, online and retained his services. When State Police Trooper Michael Proctor, a longtime Canton resident who was in charge of the criminal investigation, and his partner later came knocking, she answered their questions.

The day she returned to her Mansfield home, Read says, she was in her kitchen talking on the phone with a close friend who lived in Florida when she noticed a Chevy Silverado pickup truck parked in front of her house. Soon, she says, about six other vehicles appeared. Then, nearly a dozen police officers converged. At 7:40 p.m., officers handcuffed Read and drove her to the Blue Hills State Police Barracks.

Read spent the night in jail until the morning, when officers took her to a holding cell inside the Stoughton courthouse. Read says that she and Yannetti stood on opposite sides of the jail bars and reviewed the charging documents. The medical examiner had noted several bloody abrasions etched into O’Keefe’s right arm, two swollen black eyes, a small cut above his right eye, a cut to the left side of his nose, an approximately 2-inch laceration to the back of the head, and multiple skull fractures that resulted in bleeding of the brain. His pancreas was dark red, indicating hypothermia had contributed to his death.

The rest of the information contained in official reports was even harder for Read to hear: According to witness interviews, Read had told McCabe she had last seen O’Keefe at the Waterfall, that she and O’Keefe had gotten in a fight, and that she didn’t remember dropping him off at the post-bar gathering at 34 Fairview. According to Roberts’s account in the charging document, Read was so drunk that night that she told Roberts in the morning she didn’t remember anything from the night before—though she had wondered if O’Keefe was dead or got hit by a plow—and that Read still seemed drunk that morning. Before Roberts, McCabe, and Read found O’Keefe’s body, Roberts told police, Read showed them her cracked right taillight, saying she had no idea how it had happened the night before. When an emergency responder asked Read how O’Keefe had injured his face, the document stated, Read said, “I hit him. I hit him, I hit him, I hit him.”

In addition, it stated that Canton police found a broken cocktail glass and multiple patches of blood in the snow near where O’Keefe’s body had been located that morning. The Massachusetts Special Emergency Response Team (SERT) also found pieces of plastic—two red and one clear—in the same vicinity as the body, items consistent with the broken taillight on Read’s Lexus. The document noted that officials seized the car and found that it had broken glass embedded in the rear bumper, a deep scratch and a dent on the right side of the rear tailgate, and two scratches plus some chipped paint on the right side of the rear bumper. Considering the evidence, police and prosecutors concluded, Read was intoxicated when she backed up and struck her boyfriend and then drove off into the night.

In the holding cell, no sooner had Read and her attorney read the evidence being marshaled against her than a bailiff came for Read. He led her, wide-eyed and terrified, she says, into Stoughton District Court, where O’Keefe’s family and dozens of his friends and fellow Boston cops—including uniformed BPD Superintendent in Chief Gregory Long—packed the courtroom. On the other side of the aisle, Read’s mother prayed as a judge arraigned her daughter on manslaughter charges. Then Read entered her plea: not guilty.

Afterward, Yannetti told reporters outside the courthouse that his client was in shock and that O’Keefe’s death had been an innocent accident. Read had “no criminal intent,” he said. “She loved this man. She is devastated.”

O’Keefe’s family and friends at a pretrial hearing. / Photo by John Tlumacki/The Boston Globe via Getty Images

It wasn’t long before a far more sinister theory of what happened began to emerge. On his drive home after the arraignment, Yannetti says, he returned a call to a tipster who had previously called his office. A man with a gravelly voice—who initially offered up a fake name—picked up the phone and told Yannetti, he recalls, something to the effect of, “Your client is innocent. John was beaten up by Brian Albert and his nephew. They broke his nose, and when O’Keefe didn’t come to, Brian and a federal agent dumped his body on the front lawn.” (An attorney for the man Yannetti identified as the tipster denies Yannetti’s version.)

Yannetti didn’t know what to think. Was this even plausible? He thought about the people at the after-party that night: Brian Albert, the homeowner, was a prominent Boston cop. There was also a federal law enforcement officer at 34 Fairview that night: Brian Higgins, a special agent with the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms, and Explosives, with whom both O’Keefe and Read were friendly.

Given the new information, Yannetti and Read say they began to believe that Read was being framed. They hired a private investigator to knock on doors in Canton. Most people turned the gumshoe away, but Canton resident Tom Beatty—a friend of both O’Keefe and Read—offered up a new tidbit: His daughter, who was friends with Brian Albert’s nephew Colin Albert, said that Colin had been at 34 Fairview Road the night O’Keefe died.

When Read heard this, she says, the news transported her back to a night during the spring of 2020 when O’Keefe’s home-security alarm went off, and he bolted out of bed. She followed him down the stairs and says she remembered seeing Colin Albert and several teens in the front yard. “Go fuck yourself,” Read remembered Colin yelling at O’Keefe. “Get the fuck out of here,” she recalled her boyfriend replied. The next morning, Read says, the couple awoke to a dozen empty Bud Light cans strewn in the bushes. The police were never called, but from then on, she says, there was bad blood between Colin and O’Keefe. In fact, she now adds, Colin was the only person with whom O’Keefe ever had issues.

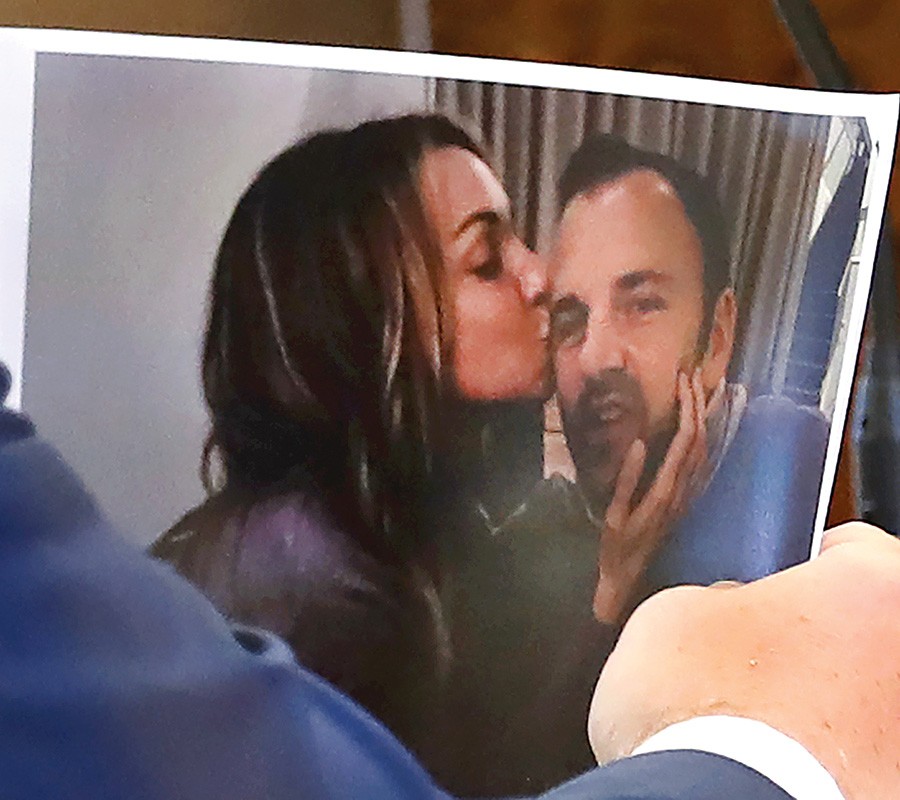

Read and O’Keefe, in happier times. / Photo by John Tlumacki/The Boston Globe via Getty Images

After hearing that Colin Albert had been present at 34 Fairview, Read says, another apparent clue in the case soon appeared when Read and her father, William, met with Yannetti in his office. For the first time, Read saw police photos of O’Keefe’s body. She could barely draw a breath, she recalls, waiting until taking the elevator back down to the lobby to break down in tears. It looked as though someone had “beat the shit” out of him, she says. As she and her father drove home on Route 93, Read called her mother and described the bizarre injuries on O’Keefe’s arm. Her mom suggested that they could have been from an animal. Read called Beatty. “Do the Alberts have a dog?” she asked. Yes, he replied, a German shepherd.

Then, three months later, Read says, a couple that Read and O’Keefe had been close to came over to Read’s house for dinner. They had just testified before the grand jury in the case, summoned along with others who appeared in Read’s call log the morning O’Keefe died. Over Italian takeout at Read’s mahogany dining room table, next to a sideboard crowded with pictures of Read and O’Keefe—one with a rosary draped across it—they told Read that State Trooper Michael Proctor, a Canton resident and lead detective on the case, had mentioned that he had known members of the Albert family for years.

To Read, that sounded like a conflict of interest. When her guests left, she went upstairs to her bedroom, pulled out her laptop, propped herself against the pillows on her enormous white bed, and started reading through Proctor’s publicly shared Facebook page. That led her to Proctor’s sister’s account, where Read says she combed through some 1,300 photos. At 4 a.m., she found what she was looking for: a photo taken at Proctor’s sister’s wedding that showed a young Colin Albert, the ring bearer. Then Read found another photo of Proctor’s parents and sister alongside members of Chris Albert’s family.

Read was speechless. As she sat there on her bed, she says, the dots in her mind began to connect, forming a theory of who had really killed O’Keefe—a theory that would prove her innocence. The way she saw it, the bad blood with Colin provided the motive for a fight inside the house that night. The Alberts’ German shepherd also jumped in, which might explain those mysterious arm injuries. Then the partiers tossed O’Keefe outside to die in the snow. The tipster’s information had already helped convince Read that she was being framed, but she’d wondered who was pulling the strings. Now, Read says, she believed she had her answer: Proctor.

Meanwhile, far from coming to the conclusion that someone else killed O’Keefe, prosecutors doubled down on their belief that Read was the killer. After the grand jury reviewed the prosecutor’s evidence, it concluded there was sufficient evidence to also charge her with second-degree murder, implying she had intentionally killed O’Keefe. On June 9, Proctor himself—along with several other police officers—walked up to Read’s home and once again arrested her.

Read was now facing a potential life sentence in prison. After posting bail set at $100,000, she went home to take a long, hot shower. This is getting real, she thought to herself. The stakes kept getting higher. She knew she needed bigger legal guns to help her.

O’Keefe’s body was found outside the home of fellow BPD officer Brian Albert. / Photo by Matthew J. Lee/The Boston Globe via Getty Images

Two months later, Read sat at her laptop, her fingers hovering over the keys. She wanted an eye-grabbing subject line for an email she was about to send to Alan Jackson, a famous criminal defense lawyer in Los Angeles who’d once defended Harvey Weinstein and Kevin Spacey. “Murder of a Boston Cop,” she typed out.

It worked. Soon after, Read, her father, and Yannetti all dialed into a conference call with Jackson, who had already received O’Keefe’s autopsy over email. As Yannetti summarized the case, Jackson interrupted: “How the fuck are they saying he got these injuries?” Between O’Keefe’s swollen, black eyes and the gashes on his arm, Read’s boyfriend appeared as though he’d been beaten up before being attacked by a dog, not run over by a car.

Read’s lawyers also realized that, according to Proctor’s original affidavit in February, six months earlier, the lead detective said he’d arrived at Read’s parent’s house in Dighton at 4:30 p.m. and towed her car at 5:30 p.m., but the Reads’ security footage (as well as the Dighton Police report) showed that those times were wrong, and that Karen’s SUV was actually towed closer to 4:12 p.m. That 78-minute discrepancy, Read and her attorneys claim, would have left Proctor alone with the car with plenty of time to break her taillight and plant the pieces at 34 Fairview for the SERT team to find when it arrived at 5:45 p.m.

Jackson officially joined the defense team and began looking for evidence that would back up their alternative theory and exonerate Read. They found suspicious details, such as Brian Albert getting rid of his dog and selling his house in the wake of O’Keefe’s death. Still, it wasn’t until early March that they found what they considered a bombshell: an incriminating Google search on McCabe’s phone, which she had turned over to the prosecution voluntarily. According to the analysis, McCabe appeared to have Googled “hos [sic] long to die in cold” at 2:27 a.m. the night that O’Keefe was killed. That was hours before the three women found O’Keefe in the snow. The same search appeared again at 6:23 a.m. and again at 6:24 a.m., after, McCabe says, Read asked her to search for it.

On April 12 of this year, Jackson submitted a 92-page affidavit to the court, laying out the defense team’s theory in detail. Read’s attorneys knew it would help their efforts if someone in the media started paying attention to their version of events: that there was more than meets the eye with this case.

Five days later, their wish came true. After multiple news tipsters told him to investigate the O’Keefe murder, Aidan Kearney, a blogger who goes by the name of Turtleboy, sat down in his Holden home surrounded by his young kids’ plastic toys and board games, and read through the case filings. (Both Kearney and Read’s defense team say they have never been in contact with one another.) Kearney, the controversial figure behind TB Daily News (formerly Turtleboy Sports) says he knew immediately that this was the kind of story his devoted followers would love. Kearney worked on his piece throughout the night, finishing it at 3 a.m. and posting it under the headline: “Canton Cover-Up, Part 1: Corrupt State Trooper Helps Boston Cop Coverup Murder of Fellow Officer, Frame Innocent Girlfriend.”

Kearney’s story laid out the theory that Read’s lawyers had presented to the court, alleging that McCabe had planted the idea in Read’s head that she might have accidentally run over O’Keefe, and implied that Proctor had planted pieces of her taillight at the scene. “Karen Read is a completely innocent woman, wrongly charged by corrupt cops who would see her rot in prison in order to cover up a murder of a fellow officer,” Kearney concluded.

Kearney suspected that as soon as he published his article, it would blow up online. He was right. His website nearly crashed under the strain of the traffic, he says. Meanwhile, back in Canton, the coverage was about to rip the town in half.

Nearly every court appearance for Karen Read has become a media frenzy. / Photo by John Tlumacki/The Boston Globe via Getty Images

The next day, news of the possible conspiracy spread like wildfire, from the deli counter at Shaw’s to the links at Brookmeadow Country Club. Before Kearney’s piece, there wasn’t much talk of O’Keefe’s death beyond those immediately involved. Suddenly, it was the topic du jour—and residents started taking sides. In response, the town’s police chief tried to ease tensions by releasing a press statement asking for patience: “[We] have heard the same sensational accounts as our townsfolk,” Chief Helena Rafferty wrote. “Unlike defense attorneys, prosecutors and police are ethically constrained to what can be said outside the courtroom.”

Kearney had no such constraints. He continued to write about the case, one story after another, as his monthly page views rocketed from about 1.5 million, he says, to as many as 4 million. He began livestreaming “Canton Cover-Up” stories twice weekly on his YouTube channel and says his viewership increased from 3,000 to 20,000 per episode.

By the time Read and her legal team arrived in court two weeks later, it was clear to Read that the tide of public opinion had turned in her favor. A crowd had gathered outside the courthouse. One person shouted, “Go get ’em, Karen,” while someone else chimed in with, “Stand tall, girl, stand tall,” Jackson recalls. Read turned to her lawyers, astounded. As the courtroom door closed behind them, the crowd applauded.

Jackson rose and presented the defense’s alternative theory, which was essentially what Kearney had posted: The witnesses in the case—those inside the house that night—had hidden evidence of the gruesome events that transpired inside the home, leading to O’Keefe’s death. Then their close friend in law enforcement, Michael Proctor, helped cover it up and frame O’Keefe’s girlfriend. The prosecutors poked holes in the defense’s theory and pushed back with their own evidence against Read.

Read with her attorney Alan Jackson, leaving court. / Photo by Matt Stone/MediaNews Group/Boston Herald via Getty Images

Meanwhile, beyond the walls of the courthouse, the town’s residents were at war among themselves. At high school games, parents who once sat side by side cheering now avoided one another’s gazes and went silent when someone who disagreed with their take on the case walked by. “My social group is really small right now because of this,” says one woman, who, like many Canton residents, asked not to be named for fear of repercussions in her neighborhood. “I only surround myself now with people that I trust.” One woman who was born and raised in Canton says, “It’s like bringing up Donald Trump at a dinner party. It could just explode. People don’t want people to know which side they’re on. Because, like politics, they don’t want to deal with the fallout.”

At the same time, though, the fault lines often seemed to take the same form as old grudges in a town where many families have lived for generations. “The problem with this town is that nobody fucking leaves,” says one resident. “Most people in Canton are turning on each other because they don’t like the Albert family, or they’re pissed that Chris Albert was elected to the Select Board, or they’re jealous of Jen from high school, or whatever these stupid bullshit things are. There are these beefs from high school with these people.”

Simultaneously, in the actual high school, students turned on one another. “You have to pick one side or another,” says one father, who saw one of his daughters kicked out of her friend group, while the other became “borderline suicidal” because he believes Karen and her friends’ parents don’t.

As the case wore on, Kearney’s role in the tabloid drama continued to expand. He became involved in a Facebook group called “Justice for John O’Keefe and Karen Read (Mass corruption),” which has more than 21,000 members who use the space to dissect nuances of the evidence, pick on witnesses, and one-up each other with hyperbolic insults.

In response, the people who were inside the home at 34 Fairview the night O’Keefe died—whom Kearney alleges are truly responsible for his death—and O’Keefe’s family members and friends started their own private group, an admin of which is a woman who used to write for Kearney until they fell out with each other several years ago, they both say. The two have been locked in battle, suing each other in court, ever since.

Kearney refers to himself as a journalist, yet he doesn’t simply publish articles or videos to make his point. He has also traveled to Canton and beyond, readers in tow, to directly confront the people he says are responsible for O’Keefe’s murder. One day, for instance, Kearney attended McCabe’s daughter’s publicly held high school lacrosse game in Billerica, while he filmed and livestreamed the confrontation for his YouTube followers. “Did you think you could outsmart Karen Read?” he asked McCabe as she sat with her oldest daughter and her friends, trying to ignore him. “Are you worried what’s going to happen to your family when you go to jail?” His readers have gone even further, texting and sending McCabe Facebook messages telling McCabe to kill herself.

O’Keefe’s family, including his brother, Paul, and his mother, Peg—who has lost two of her three children, John and his sister—arguably received the most pointed vitriol. On his YouTube show, Kearney has said: “With the O’Keefes, enough of the fucking pity party for these fucking people,” and, “The only good part about John not being alive is that he doesn’t have to be around you useless maggots for a second more. Fuck you. Fuck your high horse. Burn in hell.” Kearney says he’s offended that they believe the state is prosecuting the right person and is glad he’s able to use his platform to shine a light on the case. “The beauty of Turtleboy is that I can do things in an unconventional manner that other journalists are restricted from doing,” he says. “I love being the center of attention and being theatrical and performing. This is what I was made to do.”

As if to prove his point, on July 22, Kearney and more than 100 people—from old men with bushy beards to infants in car seats—gathered in the parking lot of a Shaw’s supermarket in Norwood and passed around markers to write slogans on their cars, including “hos long for justice?” a play on McCabe’s mistyped Google search. Then, nearly 50 cars embarked on a rolling rally through the streets of Canton while Turtleboy followers watched the livestream. Over the next two hours, Kearney—who drives a brand-new Lexus—stopped at the homes of Brian Albert, Michael Proctor, and Jennifer McCabe. At each stop, Kearney shouted into a bullhorn, detailing how each person was covering up O’Keefe’s murder. The rally ended at the Canton Police Department. Some cars passed by and honked their horns in support. Out of the window of one passing car, someone chucked an egg at the protesters.

Hundreds of Boston Police officers and Mayor Michelle Wu attended his wake but it wasn’t until a year later that the case received broader attention. / Photo by Matthew J. Lee/The Boston Globe via Getty Images

Days later, two chauffeured, blacked-out SUVs rolled to a dramatic stop in front of the Dedham courthouse, where a hundred or so people had been loudly protesting for nearly two hours under the blazing sun, holding handmade signs emblazoned with “DA Stop Lying” and “Way Beyond Reasonable Doubt.” Kearney was shouting into a bullhorn while wearing a gray “hos long to die in cold” T-shirt, which he sells on his website for $22.

The boisterous crowd quieted, just for a moment, as the driver stood by the passenger door, heightening the anticipation. Finally, he opened the door, and Jackson stepped out wearing a crisp suit. He turned and offered his hand to Read, who emerged in a tailored black suit-dress and heels. She took in the people there and beamed before walking through the crowd and up the steps into the courthouse. The onlookers then booed O’Keefe’s parents, who lowered their heads as they walked past people wearing “Free Karen Read” T-shirts.

When the doors to the courtroom upstairs finally opened, the benches on both sides of the gallery filled with spectators. Read’s supporters sat on one side, while O’Keefe’s family and friends, wearing “Justice for JJ” buttons, sat on the other. Assistant District Attorney Adam Lally walked into the room, flushed and balancing a massive stack of folders, as Read and her four lawyers sat coolly at the defense table. After arguing various motions, Lally asked the judge to compel—yet again—Read and her attorneys to allow the prosecution access to the data from Read’s cell phone. Though the state police had taken her phone into custody 18 months earlier, prosecutors had been prohibited from analyzing its contents because it contained privileged communication between Read and her lawyer Yannetti, who she’d called a few hours after O’Keefe died.

The prosecution has obvious reasons for wanting Read’s cell-phone data. After all, it could reveal who she called and texted that night and where she went in the hours before she called McCabe in the morning. This is particularly important because, according to court filings from the prosecution, O’Keefe’s Ring camera system registered 15 events between 6 p.m. the night he died and 6 a.m. the next morning, yet there is no video of Read’s arrival back home that night. Data in her phone could also help explain surveillance footage taken of Read driving toward the Waterfall at 5:11 a.m., away from the Waterfall at 5:15 a.m. and then heading toward 34 Fairview before arriving at McCabe’s that morning. What was she doing there—had she already searched for, and found, O’Keefe’s body? That might explain how she spotted O’Keefe in the dark, given that the police officer who responded to the 911 call had to use a spotlight from his cruiser to see the women crouched over O’Keefe’s body in the darkness.

Even forgoing the missing cell-phone data, though, there are some possible holes in Read’s alternative theory. For starters, the thesis that O’Keefe was assaulted inside 34 Fairview hinges on Colin Albert’s allegedly contentious relationship with O’Keefe. In an exclusive interview, though, Colin Albert told Boston that he walked out of the house at 34 Fairview right when Brian Albert was arriving, said hello, and stepped into the car of Jennifer McCabe’s daughter, who then drove him home. According to court documents, no one else, including O’Keefe, had arrived by that point. Text messages, which Boston has seen, confirm he was picked up at 12:10 a.m., and his parents say he was home for the rest of the night—all of which counters the theory that his animosity with Colin led to O’Keefe’s death inside the house within minutes of his arrival, and then his friends tossed him onto the lawn in a blizzard to die.

Also problematic for Read’s alternative theory is that, according to multiple people who know O’Keefe and Colin in Canton, it doesn’t seem there was any bad blood between O’Keefe and Colin, as Read claims there was. What’s more, two sources claim the confrontation between O’Keefe and the boisterous beer-drinking teens on his lawn that Read recalled actually involved another teen entirely and not Colin at all. And when it comes to the suspicions raised by Brian Albert getting rid of his dog and selling his house, a source with knowledge of the situation says Albert got rid of the dog after it got in a fight with another dog and that he had already contacted a real estate agent about selling his house prior to the night O’Keefe was killed. (Neither Brian nor Chris Albert agreed to comment for this story.)

There also seem to be some holes in the defense’s allegations concerning the conduct of investigator Proctor, who Read’s lawyers allege planted evidence at the crime scene. According to the DA’s spokesperson, Proctor’s police report listing the incorrect time in Dighton—supposed evidence of his having had plenty of time to plant evidence—was simply an error that was amended in later filings. Police reports and the DA also confirm that Proctor was never alone with Read’s Lexus and never returned to 34 Fairview after it was seized. An even larger problem for Read’s defense is evidence that there were microscopic pieces of taillight plastic found on O’Keefe’s shirt.

When it comes to the timestamp on McCabe’s Google search for how long it takes to die in the cold, the state’s own forensic experts say the timestamp of 2:27 a.m. was a result of McCabe typing into the search bar of a tab that had been opened at 2:27 a.m. and left open, meaning it does not prove that she executed the search at that time.

Karen Read supporters as she left the Dedham courthouse on September 15. / Photo by Matt Stone/MediaNews Group/Boston Herald via Getty Images

Meanwhile, forensic evidence calls into question other aspects of Read’s defense. According to court documents filed by the prosecutor, the medical examiner testified in front of the grand jury that the injuries O’Keefe suffered were not the result of a fight, and the marks on his arm were abrasions caused by blunt force trauma. In addition, data from Read’s Lexus, retrieved by the state, shows that her car went in reverse at a high rate of speed, and then, according to the state’s crash reconstruction, struck the victim and continued in reverse before leaving the scene.

Besides the physical evidence, another piece of the puzzle Read’s lawyers will have to explain is Read’s ever-changing narrative. According to prosecutors, O’Keefe’s niece, who Read woke up to call McCabe, says that Read changed her story multiple times when she was on the phone with McCabe that morning. And it continued to vary. Read told Proctor that she dropped O’Keefe off at Fairview and went home because she had a stomachache, and that she never saw him enter the house. During an interview with Boston, she said that she saw O’Keefe run up to the house and enter through the door of the breezeway, that she waited some 10 minutes to hear from him that it was “copacetic” for her to join him and his friends, and left when he didn’t answer her calls or come back. The theory that Read’s team espouses hinges on O’Keefe being inside the house. Yet according to a statement from Norfolk District Attorney Michael Morrissey, cell-phone data from O’Keefe’s phone, found on the grass beneath his body, shows the phone never entered the house.

What’s more, while Read has insisted that she and O’Keefe were in a loving relationship, evidence from O’Keefe’s phone shows she called him some 50 times that night, leaving furious voicemails and screaming that she hated him, according to the prosecution. And there is another potential bombshell buried in the documents concerning ATF Agent Higgins, who was in the Fairview house that night. He was the only person there who has not been the focus of Turtleboy coverage; many people in Canton say he hasn’t been heard from since the night O’Keefe died. He voluntarily gave authorities his phone, from which they retrieved some 56 pages of texts between him and Read, some of which a source with knowledge of the messages has characterized as romantic in nature. (Higgins did not respond to requests for comment.)

None of this takes into account the fact that prosecutors have evidence they have yet to publicly share and probably won’t release until the trial, which is currently set for March 12, 2024. To accept Read’s alternative theory, jurors will have to believe that there was a conspiracy among officers from multiple law enforcement agencies, an emergency responder, several witnesses, a medical examiner, forensic computer experts, O’Keefe’s then-14-year-old niece, and his childhood friend, who didn’t even know any of the people who the conspiracy is allegedly protecting, in order to frame Read. All they need, though, is reasonable doubt in the defense’s case. And Read’s freedom might just depend on it.

On Sept. 15, hundreds of Karen Read supporters gathered in front of Dedham’s Norfolk County Superior Court before Read’s latest court appearance. / Photo by Matt Stone/MediaNews Group/Boston Herald via Getty Images

Still months away from a trial, the case is already making the Hollywood rounds. Dateline has been filming Read for a show scheduled for release after the verdict, and Kearney says he has been approached by multiple documentary producers, including a few from Netflix. Meanwhile, in Canton, the community continues to convulse under the weight of the tabloid drama. On August 8, residents packed the second floor of Memorial Hall for the Canton Select Board meeting to voice their concerns about Selectman Chris Albert, the Canton Police Department, and their otherwise quiet and peaceful suburb being portrayed as a national disgrace. Police Chief Rafferty took the microphone and said she could understand people having questions about the O’Keefe case based on the limited information publicly available, but what was unacceptable was witnesses—residents who had not been charged with any crime—being bullied and harassed by either side of the case under the guise of the First Amendment.

Several weeks later, Norfolk DA Morrissey followed up with a recorded video message. Seated in front of a bookshelf of legal tomes, he mentioned evidence that counters much of Read’s alternative theory and pleaded with the public to stop harassing the crime witnesses. “We try people in the court and not on the Internet for a reason,” he said, adding that this was the first and only time during his dozen-year career he’d felt compelled to record such a message. “The Internet has no rules of evidence. The Internet has no punishment for perjury. And the Internet does not know all the facts.”

A couple of weeks after that, at a regularly scheduled town Select Board hearing, a resident speaking into the microphone broke down in tears. “It’s been a long 19 months,” she said, adding that she wanted to see an independent investigation of the crime to get to the bottom of the incident that has divided her town.

There is one thing that almost everyone in Canton seems to agree upon: O’Keefe was a good man and a selfless person who, after losing his sister, stepped up to raise her children with love and devotion. He was universally liked in a town that has descended into bitter strife over his untimely death. Still, for now at least, people in Canton are so busy fighting over whether Read is a criminal or a victim of police corruption that no one is talking much about O’Keefe.

*Update, Sept. 27, 4 p.m.: Two sentences in this story have been revised, one for clarity, one for accuracy. 1) Court documents state that no one else had arrived at 34 Fairview at the time that Colin Albert left. 2) An earlier version of this story characterized Jennifer McCabe’s daughter as Colin Albert’s “cousin”—Jennifer McCabe’s daughter and Colin Albert are not blood relatives.

An earlier version of this story was published in the print edition of the October 2023 issue with the headline, “The Killing That Tore a Town Apart.”