Inside the Bunker with Michelle Wu

Almost halfway through her inaugural term, the city's youngest modern mayor is winning fans, battling critics and watching the clock. Can she make a better, more equitable Boston before time runs out?

Photo by Tony Luong

Mayor Michelle Wu has a clock on her phone that keeps track of exactly one thing: the number of days she has left in office. Today, though, the busiest woman in Boston is probably just counting down the minutes until our interview is over so she can finally eat. She’s sitting with me at a conference table in her fifth-floor City Hall office, wearing a sporty black denim dress with an untouched bagel and cream cheese in front of her. With all my questions, Wu hasn’t even had a chance to take a bite. As she talks, she grabs her phone and swipes at the screen until she finds the countdown calendar. “We have 883 days left in the term,” she announces with a sense of urgency.

“But who’s counting?” I respond.

That gets a laugh, but I know the answer already: Wu is. Always. She is acutely attuned to the passage of time, and not, she says, because she is in a hurry to get out of office (although it is often rumored that she is), but because she has a lot to get done. The sheer scale of what she is hoping to accomplish during her time as mayor—to make the city more equitable, green, and livable—requires nothing less, she says, than addressing decades of unmet needs and deeply ingrained problems, shifting priorities, and running the mayor’s office differently than in the past.

In fact, there’s a lot about Wu that distinguishes her from her predecessors—beyond the obvious fact that she is a 38-year-old woman of color. From where she hails—geographically and generationally—to how she campaigned and won to her vision for the city’s future, Wu is simply a different kind of mayor than what Bostonians are used to. As Reverend Jeffrey Brown, a social activist and associate pastor at Twelfth Baptist Church in Roxbury, summed it up, “Michelle Wu is willing to do business unusual.”

Wu at a recent public event addressing the audience. / Photo by Barry Chin/The Boston Globe

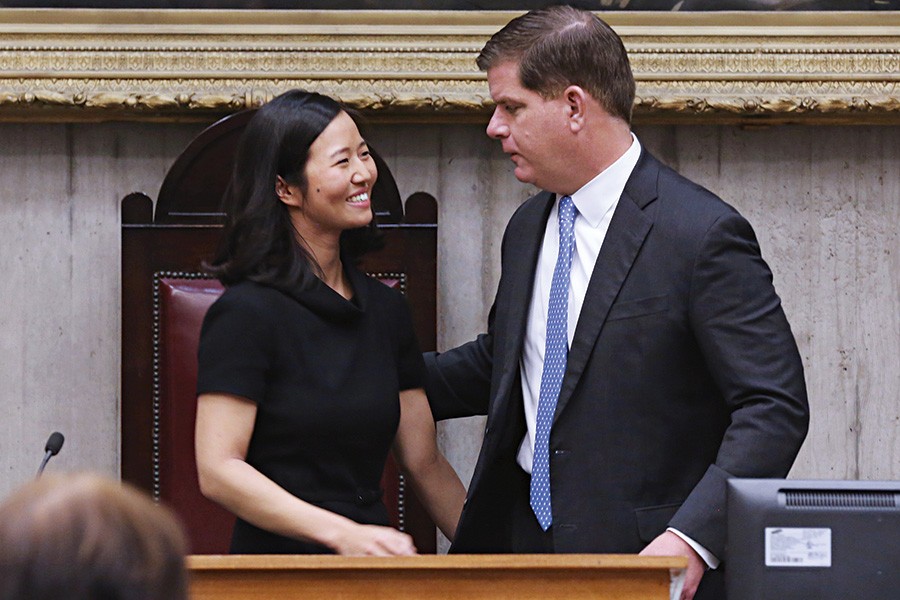

That’s not the only way that Wu is different from the past couple of elected mayors. Where Thomas Menino was the urban mechanic who filled potholes, and Marty Walsh was the labor movement’s dream come true—both charismatic and attention-seeking—Wu is more of an introvert and a technocrat. When she’s out at community events, she often relinquishes the mike to deputies and other elected officials. She also delegates many responsibilities and meetings to her cabinet members instead of taking them on herself. “I don’t love being the center of attention,” she tells me as she sits in her massive office, the city’s epicenter of power.

All change involves some degree of loss, so naturally, not everyone around town is on board. Wu’s ambitious plans for Boston have earned her sharp and vocal criticism from the business community, particularly among real estate developers, who believe she is changing too much, too fast, and putting the city on a course toward financial disaster. More recently, she has also taken heat from some of her early supporters, who now say she isn’t doing enough, or moving fast enough, to fulfill her campaign promises. It seems Wu’s critics are acutely aware of time, too.

As my allotted minutes with Wu tick away, I consider how rare it is to meet with the mayor like this. I have Wu all to myself, and I’m getting a chance to know her. I also understand that not everyone has had this opportunity: Influential decision makers have complained that they aren’t getting the one-on-ones they’ve previously gotten with other mayors. All of this means that many people don’t tend to get a good sense of her personality—which, in turn, provides a vacuum for rumors to fester and grow. And the Boston rumor mill is churning overtime when it comes to Wu.

For her part, as she enters the third and most critical year of her term, Wu tries to tune out the noise and work with purpose. “I move with a sense of impatience to get things done and to make the changes that are necessary,” she tells me. “But I also want to ensure that changes are lasting and not just a Band-Aid. That takes getting down to the roots of our challenges, building the capacity to take it on, the systems to sustain it, and to keep it going and ensure the solutions are having actual impact.”

That also takes time. And as Wu knows better than anyone, the clock is ticking.

Wu in her fifth-floor City Hall office. / Photo by Tony Luong

Like many working parents, Wu is keenly aware that disaster awaits those who don’t heed the clock. I’m with the mayor in her official city car as we head to the next event on her tightly choreographed schedule when the next potential disaster arises: Her two well-behaved children are one snack away from getting hangry.

Like Senator Ed Markey, Wu has made combatting climate change a focus of her work. / Photo by Matt Stone/MediaNewsGroup/Boston Herald

We’d started the day at a press conference in Dorchester with Governor Maura Healey and U.S. Senator Ed Markey. After that, we raced over to a West Roxbury tennis camp to pick up Wu’s sons, Blaise, 8, and Cass, 6. Then we are scheduled to drive to the Seaport to board a police boat headed for Long Island to visit Camp Harbor View, a summer program that caters to underserved Boston kids. As we make our way to the waterfront, Wu pulls out the books she brought for them to read, organizes the layers she packed in case it’s chilly on the boat, and then realizes she’s forgotten the snacks. She hands Cass her own half-finished smoothie from our first stop of the day at a juice bar in Mattapan, but that isn’t going to cut it. Ever the problem solver, she tells her driver to stop at Top Bread in Chinatown so she can get one kind or another of stuffed, sticky, delicious-looking goodies for the boys. When she walks up to the register to pay—refusing to accept freebies from the starstruck staff—she speaks to the cashier in Mandarin.

As I watch the scene unfold, it is hard not to notice some of the things that set her apart from previous mayors: Wu is a woman, she is a millennial, she is a mother, and she’s Asian American. What’s more, Wu was not born or raised in Boston, a fact that Annissa Essaibi George, who ran against her in the 2021 mayoral race, tried to use against Wu during the campaign. Instead, Wu grew up in Chicago, the child of Taiwanese immigrants, and she came to Boston on the most coveted of first-class tickets: admission to Harvard. After graduating, she worked as a consultant for the Boston Consulting Group until her mother’s mental health crisis forced Wu to return to Chicago. She helped care for her mother and two younger sisters before eventually returning to Boston with her family to pursue a law degree at Harvard. During graduate school, she interned at City Hall, where she impressed high-level staffers with her devotion to the job. In the classroom, meanwhile, she impressed her law professor, Elizabeth Warren, with her work ethic and intellect.

Wu studied under Elizabeth Warren at Harvard Law School and worked on her first Senate campaign in 2012. / Photo by John Tlumacki/The Boston Globe

After earning a JD degree, Wu jumped headfirst into electoral politics and reunited with Warren, who in 2012 was making her first run for the U.S. Senate. “She took a very responsible job on my campaign—which was really a 24/7 job—at the same time that she was caring for her two younger sisters and her mother,” Warren says. “And right in the middle of all that, she planned [her] wedding. Michelle takes organization and hard work to an all-new level.” A year later, Bostonians elected Wu to city council, and from 2016 to 2018 she served as president. She remained on the city council until she was elected mayor.

Even before she set foot in City Hall’s most important office, Wu began shaking up politics-as-usual by becoming the first candidate to win the race based on ideology—in this case a progressive one—and not by cobbling together enough neighborhoods to triumph. “The old-school way of winning in Boston was always, ‘I come from this neighborhood, and I’m going to pick up that neighborhood, and then that neighborhood,’” says state Representative Aaron Michlewitz, a close friend of Wu’s. “I can’t even tell you where her base is from a neighborhood standpoint. That changes the entire dynamic of the [campaign] to something that many people aren’t used to.”

As mayor, Wu acted differently than her predecessors, too. Menino and Walsh had felt the need to be seen everywhere—Menino because he was notoriously insecure and Walsh because he wanted to help everyone, says a political consultant who asked not to be named. “We had two mayors who were the nerve center for everything that happened in the city,” the consultant says. “And it created a culture, and ultimately a set of practices inside and outside of city government, that made the mayor the focal point for every decision. Big decisions, small decisions, things that belonged in the mayor’s office, and things that didn’t. Everybody inside city government was looking to the fifth floor to get direction, and everyone outside City Hall who wanted something would bring it to the mayor.”

With Wu, Bostonians suddenly didn’t see their mayor out all the time, cutting every ribbon and attending every gala. Some critics questioned whether she was even doing anything at all. In response, Wu tells me it would be impractical for her to make every decision. “There are simply too many issues we need to move forward on and initiatives that we need to be pushing all at the same time for me to be personally involved in everything.” After all, she isn’t just changing the way the mayor’s office is run; her end game is to change Boston.

Wu at a recent public event sitting with members of her staff. / Photo by Barry Chin/The Boston Globe

After our pit stop in Chinatown, Wu, her sons, and I make it to the police boat, which ferries us to Long Island, home of Camp Harbor View. When Wu arrives, the campers are already seated in an outdoor amphitheater, wearing their colorful camp T-shirts and waiting quietly for their guest speaker. The camp director walks onto the stage and announces that the “most important person in Boston” is here to see them.

I had spent just enough time with Wu to know that this is the kind of comment that wouldn’t sit well with her. During my time with her, she’d only used the word “we,” and not “I,” when speaking about her policies, initiatives, and accomplishments, and I never once saw her get in the back seat of her official chauffeured vehicle—unless her kids were with her. She seemed genuinely surprised the first time I rode in the car with her and mentioned that I’d expected her to ride in the back. So at the camp, I presume that Wu will simply ignore the introduction and maybe cringe a little inside. Nope. With only an instant to think, Wu grabs the mike and opens by saying, “I decided to come spend time with the most important people in Boston, who are here today.” The kids go wild.

Once the noise simmers down, Wu gives a seconds-long introduction and then takes questions. Hands shoot up.

“What are you going to do about the extremely high costs of rent?” the first camper asks.

Wu looks offstage at her staff members, crowded beneath the shade of a nearby tree, her mouth agape in delighted disbelief. If the camper asking the question wasn’t 11 years old, I might have thought Wu’s aides had planted the boy in the audience. After all, his was a pitch-perfect question for a mayor who has made easing Boston’s housing-affordability crisis her trademark goal. “That’s the number one issue in Boston,” Wu responds. “We want to be a place where kids have every opportunity, where our seniors who have put their whole lives into Boston can stay.” Then she explains what her administration is doing about it, including an audit of every piece of city-owned land, from parking lots and swaths of grass to the air rights above a low-slung library, that the city is now offering to developers to build more housing, so long as it is all affordable. She notes that her administration has also made an official petition to the state legislature for rent stabilization, which would cap rent increases and address the camper’s concern.

Wu’s sons, Blaise, 8, and Cass, 6, sometimes tag along with their mom on official business. / Photo by Jessica Rinaldi/The Boston Globe

Wu doesn’t go into much more detail on housing. After all, there are other kids with burning questions, such as whether they can get better school lunches and what to do about a noisy neighbor. But she is doing more. The mayor upped the minimum percentage of units in new buildings that must be affordable from 13 to 17 percent (with plans to take it to 20), and in July, she announced a residential tax break of up to 75 percent for developers who convert vacant downtown office space into residential units. While she isn’t exactly abolishing the BPDA—as she promised with much fanfare as a city councilor and mayoral candidate—she is reforming the agency, including bringing many of its functions under city control. She is also overhauling the city’s arcane zoning code.Housing, though, is just one pillar of Wu’s vision to make Boston “the best place in the country for families,” as she’s said. She has also designated $2 billion for new school construction and renovations, negotiated a landmark agreement with the teachers union to reform special education, and completed a strategic plan to expand multilingual and multicultural education. And when it comes to the environment, she has enacted policies to make affordable housing and school buildings more climate-friendly, abolish fossil fuels in new city-owned buildings, and implement a green building code aimed at reducing the use of fossil fuels in new real estate development projects.

In other words, Wu has big ideas about the future of Boston. Not everyone thinks her vision for the city is going to make it better, though. And there are already rumblings about who could replace her.

Wu has BIG IDEAS about the future of Boston. Not everyone, though, thinks her vision for the city is going to make it BETTER.

Not a day goes by, it seems, without another rumor about Wu. There is speculation that she “hates the job,” as some have told me. There are rumors that she has regular work-induced panic attacks for which she has sought medical attention. There was even a season of rumors this year that she was pregnant and went on vacation to figure out how to handle it.

That’s not all. Some people I spoke to seemed willing to bet money that Wu won’t run for mayor again. Others told me she really has her eyes on national office and that she is just using Boston as a brief steppingstone. And several weeks after Wu and I met at City Hall, the Boston Herald reported she wasn’t even planning on finishing the term and was in conversations with Harvard University about a job that would give her an emergency exit ramp from the mayorship. Several weeks after that, the rumor du jour was that Wu would resign in January after supporting her pick for city council president, who would then take over the mayor’s office.

When I ask her about the rumors, I get an eye roll and a slightly exasperated shake of the head. Wu says she loves her job and isn’t going anywhere. “I mean, I just feel so lucky and blessed to be able to get the chance to do what I do every single day,” she tells me. And the whispers about her mental health? She insists that if she were seeking treatment, she, of all people—who was so open about her mother’s struggles—would be transparent about it because she wouldn’t want to stigmatize mental health struggles. She’s also quick to point out the inherent sexism in such rumors. “I think women in leadership have experienced this for generations—[people questioning] whether you are ‘in over your head’ or ‘able to handle such difficult, hard things,’ and whether the ‘emotion of it is overwhelming,’” she says.

Regardless of whether there’s any truth to the rumors, one thing is certain: There are people who are convinced that Wu isn’t good for Boston. And some of them are talking about who could run against her in 2025. This summer, for instance, a mysterious press release landed in the inbox of the Dorchester Reporter about an event that public relations mogul George Regan (Regan Communications Group represents Boston magazine) was hosting at his Mashpee home. The email billed the event as a fundraiser for City Councilor Ed Flynn, a birthday party for his father—former Boston Mayor Ray Flynn—and the launch of a group dubbed “Save Our City,” described as a “3-year mission to save the City of Boston from the negative impacts of the ultra-progressive policies [that] dominate the current city council and current administration at Boston City Hall.”

When the newspaper contacted invitees to ask about the campaign, they said they thought the party was just a fundraiser/birthday party and had never even heard of “Save Our City.” When the newspaper reached Regan, he said his secretary was responsible for the error, but insisted the city did need saving. In no time, the whole debacle turned into a punchline. One person told me, “Nothing says ‘Save Our City’ like a meeting on the Cape.” In response, Regan said that the party on the Cape was not for “Save Our City” but for Ray Flynn.

Still, the discontent among some stakeholders is anything but a joke. The belief that the city needs to be saved from an “ultra-progressive” agenda is one that’s shared by a group of influential people who have grave concerns about Wu’s approach to business, in particular real estate development.

Some developers have long grumbled about Wu’s affordable and climate-friendly requirements for new residential projects, which, given the current high interest rates, make it so that constructing new buildings is no longer profitable. They predict that Wu’s changes will have the opposite of their intended effect, resulting in fewer new affordable-housing units than under previous administrations since fewer projects overall will be built. Indeed, the number of approved projects for which developers are requesting permits to start building is down about 25 percent compared to the average over the past decade.

What’s more, a decrease in new development would have a disastrous effect on the city’s entire economy, some business leaders say, given that the vast majority of the city’s operating budget comes from taxes, fees, and permits related to real estate. “That’s the goose that laid the golden egg” in Boston’s growth over the years, one local businessperson told me. “I worry that trying to change things too fast, especially in a difficult business climate, is a recipe for killing the goose.”

Other critics expressed concerns about the way City Hall itself is run. Wu’s administration, they believe, is filled with young, inexperienced hires, many of whom are not from Boston, don’t know the city, and are out of their depth. One Boston businessperson told me that Wu, while smart, lacks the management experience needed to run an organization as large as the city of Boston without more experienced staff to support her. And her critics in the business world complain of not getting the one-on-one meetings that they were used to having with previous mayors.

Developers aren’t the only ones grousing about Wu. In the wake of complaints about noise, garbage, and traffic, in March 2022, the mayor announced that North End restaurants would have to pay a $7,500 fee if they wanted to offer outdoor on-street dining. Soon after, Wu was hit with a lawsuit alleging she discriminated against the restaurant owners for being white Italians. (The lawsuit was later dropped.) Meanwhile, new bike lanes in traditionally white and more conservative West Roxbury have also been a lightning rod of discontent among residents who say they create more traffic by reducing space for cars.

Regardless of whether there’s validity to the criticisms of Wu’s policies, the conventional wisdom among analysts and observers is that many detractors feel threatened by Wu’s quest to give a seat at the decision-making table to people who have never had one. “There’s a community in Boston who has always had outsize influence over many matters in Boston, who now have a voice and a vote, not more, not less,” says Democratic strategist Mary Anne Marsh. “It is not that they are being knocked out, but she is putting everyone at the table. She’s trying to make sure that there’s wealth and equity for everybody and all the neighborhoods in Boston, not just a select few.”

There are clearly new chairs at the table. Wu has invited representatives of the Black Economic Council of Massachusetts and Amplify Latinx, which represents Latinx business owners and leaders, to quarterly meetings she holds with other business organizations like the Greater Boston Chamber of Commerce, and she has made it a point to take meetings with Black developers. “Wu really concentrates on the needs of those who might find themselves on the margins of society or have been sort of cut out of the system, if you will,” says Reverend Jeffrey Brown, whose nonprofit My City at Peace, along with HYM Investment Group, has won a contract to develop a city parcel in Roxbury. “Those of us who never had those perks are her cheerleaders.”

Despite Wu’s work to bring more Bostonians to the table, as well as the many leaders and businesspeople of color who told me she is doing more for their communities than prior mayors, not everyone in the Black community is happy with her performance so far. In fact, some of the very people who should be benefiting from Wu’s new way of doing business at City Hall are just as upset with her as anyone.

The mayor discusses her proposal to move the John D. O’Bryant School of Mathematics and Science from Roxbury to West Roxbury, a move that has upset many people in the Black community. / Photo by Jonathan Wiggs/The Boston Globe

Another day this summer, Wu is standing inside the cavernous West Roxbury Education Complex, which has been empty since 2019. The place smells stale, and dust covers the furniture that’s been sitting there since the building started serving as a storage space. “It needs significant work, but it really has the space and all the bones here for what would make for a remarkable campus,” Wu says before showing reporters renderings of a modern school featuring gleaming glass and contemporary lines. “There’s a chance to build this out to really put another shining star in the BPS universe.” This new state-of-the-art building would be home to the John D. O’Bryant School of Mathematics and Science, one of Boston’s three exam schools, which currently shares a campus with the Madison Park Technical Vocational High School in Roxbury.

To many in the Black community, though, it doesn’t matter how amazing the school looks on poster board—that it has a pool and vast athletic fields, and that the larger building would allow enrollment to increase by 25 percent. What they find most significant—and infuriating—is that the school would be relocated here, to this corner of Boston, from its location in Roxbury.

Several weeks earlier, some O’Bryant parents expressed shock when the idea was first announced at a news conference outside Madison Park. A particularly incensed O’Bryant mom strode up to Wu and confronted her. “Why West Roxbury?” the parent recalls saying. “Historically, West Roxbury hates Black and Brown people. We can’t get there. They don’t want us there.” In fact, many other residents of traditionally Black neighborhoods in Boston believe that West Roxbury’s distance from the heart of Boston and inaccessibility on public transit will decrease enrollment of children of color in what is currently the city’s most diverse exam school.

The school isn’t the only thing that some members of the Black community are upset about. Local leaders told me they believe Wu has changed since she served on the city council and is failing to live up to the promises that she made on the campaign trail. Louis Elisa, the former president of the NAACP Boston Branch, takes issue with the fact that, despite promises to the contrary, Wu has not increased the percentage of city contracts that go to Black business owners.

Still, perhaps no other issue has upset some residents of color more than Wu’s decision to veto the city council’s proposal to switch from an appointed to an elected school board. Nearly 80 percent of Bostonians said in 2021 that they supported an elected body, and it is particularly popular among Black residents, local leaders say. Wu had originally supported a hybrid of elected and appointed members but now says it is not the right time to change the council composition, because the school system needs stability.

Meanwhile, several leaders of color sounded a lot like white businesspeople when they complained to me about a pattern of ignored phone calls, canceled meetings, and inexperienced staffers over at City Hall. “We demand to be heard!” said one exclamation-point-laden letter to Wu from the District 7 Advisory Council, which represents organizations in neighborhoods including the South End and Roxbury, that complained about unanswered correspondence.

Java with Jimmy talk-show host Jimmy Hills, who first met Wu when they were both working at City Hall during the Menino administration, says he believes Black Bostonians would give Wu a C-plus to B-minus so far. He thinks the general perception in the Black community is that “policies that a lot of Black and Brown folks are waiting for in economic development, housing, and equitable education need to come a little quicker.”

Several critics even go so far as to say that it isn’t a question of pace but one of race itself. “You can’t fake the funk, man,” says one Boston leader of color. “Like, people know if you don’t have a love for them, and I just don’t know if Michelle loves people of color. I’m sorry to say that, but I don’t think she has a deep understanding of what our people need.” Two other leaders of color agreed with that sentiment.

There is also discontent with Wu among other groups who supported her during her campaign. Ford Cavallari is the chairman of the Alliance of Downtown Civic Organizations, which advocates on behalf of nine of the largest resident associations in downtown Boston. Cavallari says his organization was overwhelmingly behind Wu when she was on the city council and running for mayor but that today, the association members’ sentiments toward Wu skew negative.

Among the complaints? That Wu has not fulfilled her promise to abolish the BPDA and that her reforms actually enshrine the status quo and give the development agency even more power. Other members of the downtown association are upset with Wu’s failure to address the Mass and Cass homelessness crisis in an effective way and with what Cavallari calls a bizarre “obsession” with bike lanes as the answer to almost every transit-related issue. “Not only were we on the Wu train, but we fancied ourselves associate conductors,” he tells me of the close working relationship between the group’s associations and Wu’s campaign. “And it’s like we’ve been jettisoned off the train in ejection seats, and the train would rather roll over us than stop to pick us up.”

When I asked Wu about these criticisms, she seemed surprised but was diplomatic and preferred to discuss how her record reflects her dedication to serving communities of color. She told me she’d recently agreed to meet with the alliance and has the most diverse leadership in the history of the city. Her office points out that while the percentage of city contracts going to women- and minority-owned businesses is stuck at a stubborn 5 percent (exactly where it was before Wu took office), the percentage of dollars going to these businesses has more than doubled. Wu’s office also says that in the first phase of the program to develop vacant city-owned lots, 13 properties are being awarded to local minority developers for projects in which 100 percent of the units are designated for affordable homeownership. “All of the work that we’ve been doing,” Wu says, “ultimately has been around delivering on racial justice and equity.” Meanwhile, even as some of Wu’s original supporters fade away, it seems the business community may slowly be coming around to her.

Both Wu and Governor Maura Healey shattered glass ceilings when they were elected. / Photo by David L. Ryan/The Boston Globe

When Wu took to the podium during a Greater Boston Chamber of Commerce meeting in September at the Fairmont Copley Plaza, she received a thunderous round of applause that initially prevented her from starting her speech. She raised her hand and shook her head while smiling as if to say, “Please stop.” But the applause just kept on.

As the crowd finally settled down, Wu enthusiastically announced: “Welcome back to fall.” Later she explained, “In my household—and I think there’s maybe a few others out there who are parents of young kids—fall is especially exciting because school is back. We get to leave behind the improvisation of summer, the go-with-the-flow of whatever might happen, and bring back the structures of having some organization around the school year.”

Wu went on to say that the rhythm of business in Boston was also back, detailing indicators that point to an economic recovery. She also mentioned having recently “met with dozens of our CEOs” and ended her presentation to a standing ovation. The warm reception may have had something to do—at least among those in real estate—with the announcement that day that her administration was considering a time-limited tax incentive for developers who get shovels in the ground on already approved projects that haven’t begun construction due to the current expense of building in Boston.

Still, the thing that most struck me from the event was Wu’s comment about her children being back in school. When I was trying to secure time with Wu for this story, I caught up with her at White Stadium, where she was speaking to reporters about a massive renovation to the stadium that will eventually be home to a professional women’s soccer team. As we walked along the decrepit track, she apologized for the delays in setting up an interview. She told me the summer had been a tough time for her family, and she had only just secured spots for her kids in camps. It was already mid-July.

My first reaction was that Wu was normalizing “parenting while in power” by talking openly about it. My second reaction was surprise that the mayor of Boston couldn’t get her kids into camp. So I brought it up one day when we were riding together in her car. She sighed and told me about wanting to enroll her kids into camps that would let them explore their own interests—something she didn’t get to do when she was a child, and her parents expected her to be a doctor—as well as the early camp deadlines for spaces that filled up fast. “I mean, it’s just like last year, the night before school started when I was at Staples, and they were all out of yellow folders,” she said, adding, “There is a lot to juggle.”

There sure is. When Wu first took office, she started out with a lot on her plate, including angry protesters upset about vaccine mandates who demonstrated almost daily—not at City Hall Plaza, but outside the home where she lives with her husband, Conor Pewarski; two small children; and a mother who suffers from mental illness. No one I spoke to could recall another mayor who had people protest at their residence. One day, she told me, her older son Blaise, who was still learning to read at the time, looked at the mail and announced that the protesters had written her a letter. Wu grabbed the envelope. It was addressed to the Honorable Michelle Wu; her son thought it said the “Horrible” Michelle Wu.

Marty Walsh was the last in a long line of men to serve as mayor, before Wu became the first woman—and person of color—elected to the office. / Photo by Angela Rowlings/MediaNewsGroup/Boston Herald

Wu has faced several other unique challenges during the first half of her term. For starters, former Mayor Marty Walsh is more active than some previous ex-mayors, showing up at events and endorsing candidates as though he were still mayor—or were thinking about becoming mayor once again. Also, when Wu came into office, all 48 union city contracts were expired—some of them for quite some time—which has never happened to a new mayor before, her team says. Her administration had to negotiate these contracts while conducting multiple national searches to fill key positions that were vacant or about to be vacant, including superintendent of schools, police and fire commissioners, and many other leadership positions. And although she doesn’t mention it, Wu was just 36 years old at the time. She had been on the city council for years but had never run an organization or company, let alone one close to the size of city government. Meanwhile, her staff was also young and, in some cases, green.

On top of it all, Wu has staked out an incredibly ambitious agenda for broad social change, not just a few tweaks to the status quo. Given all that she’s faced and what she aims to do, some local leaders—including at least one real estate developer—think Bostonians should be a little more patient. While Peter Spellios, a principal of Transom Real Estate who served on an advisory committee for Wu’s inclusionary development policy, doesn’t always agree with the mayor’s positions, he believes Boston has no choice but to tackle the issues she is trying to address, particularly around development. “All of her predecessors made the easy decisions, and only the tough ones are left,” he says. “I value the fact that she is willing to expend the political capital and, frankly, the emotional capital of trying to deal with the hard issues. I think she has earned the space for us to give her the opportunity to work on some of these marbleized problems.”

As the clock keeps ticking, it is unclear whether Wu’s critics and the rumormongers will give her the space or time that Spellios and others believe she deserves. For her part, Wu believes she is turning a corner. When I spoke to her in late September, she told me that it had taken until now to get her house in order, including making the necessary hires and laying important groundwork. The impact of those efforts, she says, is just starting to be felt.

I don’t know how many days her countdown clock said she had left in the term when we spoke that day, but after we hung up, I did a slightly different calculation of my own: She had 776 days until election day 2025.

First published in the print edition of the November 2023 issue with the headline, “Inside the Bunker with Michelle Wu.”