Why I Did the Charles Stuart HBO Doc

And why Jason Hehir's Murder in Boston: Roots, Rampage & Reckoning matters so much.

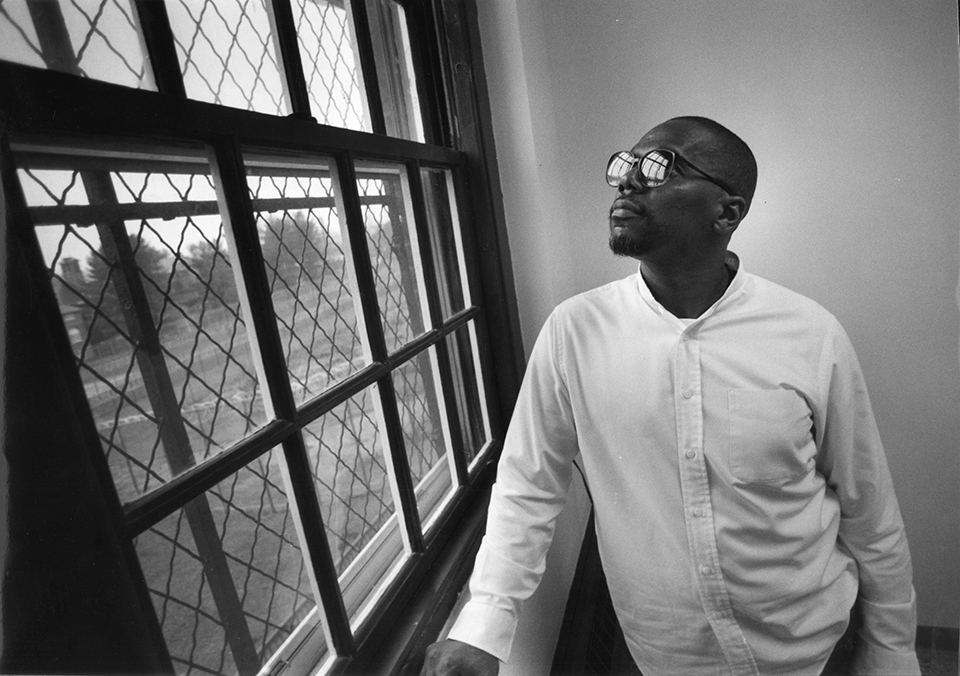

The author in Murder in Boston: Roots, Rampage & Reckoning. / Courtesy of HBO

Murder in Boston: Roots, Rampage & Reckoning is a three-part HBO original documentary series exploring Boston’s history of race-based hostilities against the backdrop of the notorious Carol Stuart murder in 1989. The third and final episode airs on Monday Dec. 18 at 9p.m.

One evening in November 2021, my phone lit up with a direct message on Instagram from documentarian Jason Hehir. I immediately recognized the name. I am an avid basketball fan and had seen his ESPN docuseries The Last Dance about Michael Jordan. Hehir told me he was about to start production on an HBO documentary about the Charles Stuart case and wanted to meet to talk about the possibility of my participating in the project. It made sense: After all, in 1989, I was a Black teenager living in Boston when Charles Stuart told a police dispatcher that a Black man had carjacked and then shot him and his wife, Carol, and I have spent much of my career trying to give a voice to Black Bostonians.

It’s incredible to think it’s been 35 years since the Stuart case rocked my hometown, where then-mayor Ray Flynn vowed the police would leave no stone unturned in their search for the killer. Over the next few months, Boston police officers terrorized and harassed Black men and boys in the Boston neighborhoods of the South End, Lower Roxbury, Roxbury, and Dorchester in search of leads. At the same time, detectives ignored many leads pointing to Stuart as the shooter and instead arrested Willie Bennett on suspicion of committing the heinous crime. Ultimately, the truth did emerge: Stuart had killed his wife and unborn child to collect her life insurance. Before he was arrested, he jumped to his death from the Tobin Bridge.

William Bennett, in 1992 at the state prison in Gardner, Massachusetts. Bennett was the prime suspect in the murder of Carol Stuart before suspicion shifted to Carol’s husband, Charles Stuart. Charles committed suicide shortly after. / Photo by Suzanne Kreiter/The Boston Globe via Getty Images

There are a few reasons I agreed to be part of this documentary. I appreciated how in the Michael Jordan series Herir painted such a rich picture of Jordan by providing such ample context and the perspectives of so many people who knew him. I also liked that Hehir grew up in Newton and would know the players in the Stuart case and who to ask to participate. Still, the biggest reason I agreed to be in the documentary was because, despite the unbridled media frenzy over this case at the time, the world never got to hear the perspective of Black Bostonians who were essentially under siege by police in the months following the murder. Officers stopped, searched, interrogated, and threatened Black teens in what can only be called an abuse of power. My friends, classmates, and even I, were among those boys.

The description of the killer was vague: a Black man in his mid-twenties or early thirties in an Adidas tracksuit who was around 5’10”. At the time, I was around 5’8″ and it was obvious I was a child when the police stopped me as I walked down Mass Ave with a book bag on my back right after school let out. The cops asked me if I was affiliated with any gangs, if I sold drugs, and if I had a criminal record. I responded “no” to all their questions and told them I was a student at Boston Latin School and was only 14.

They rifled through my bag and almost seemed disappointed to find a Latin book, an English book, and a history book instead of drugs or weapons. They let me go and told me to go home and stay out of trouble. I felt no relief because I knew they were headed off to harass another person who had no connection to the case whatsoever.

I also agreed to participate in the documentary because the Charles Stuart case is one of the reasons Boston still retains its reputation as a racist city. The mess created by Charles Stuart exposed an ugly side of Boston, a city that constantly touts itself as a learned, progressive, town of liberals and the cradle of liberty; a claim that was not—and still often is not—true when it comes to the treatment of its Black population.

Carol and Charles Stuart on their wedding day.

Charles Stuart’s account of his carjacking, robbery, and shooting was met with skepticism by many in Boston’s Black community but the entire story was bought hook, line, and sinker by most of Boston’s white residents. It wasn’t lost on us that 1989 had been one of the bloodiest summers in Boston’s history and the violence didn’t peter off as we entered the fall that year. Yet, there wasn’t any uproar, outrage, or any actions taken by city hall in response to the violence. Then Carol Stuart—a pregnant, white woman—was murdered in October. The murder sold newspapers and was the lead story on the nightly news on every local television network, stoking fears in the suburbs among white residents who had cared little about Boston’s violence until one of their own was affected. Politicians called to reinstate the death penalty.

Earlier this month, when I watched an advanced screening of the Stuart documentary before the first episode aired, I wondered how many of the people who were saying racist things and harming Black kids depicted in the archival footage might still be alive today. I wondered if they passed their belief system and prejudices on to their children.

The documentary will undoubtedly re-open many old wounds, dredge up many bad memories, and expose the ugly underbelly of Boston’s racist past. It will be triggering for those of us who lived through the events and even for those who will be learning about it for the first time. Still, it is important we all see it. We can’t bury the ugly parts of our history. We need to deal with them head on and acknowledge the harm done. If we don’t learn from our past, we’re doomed to repeat it.

For my part, I remember everything about that moment in Boston. I also remember being angry at the time. I was incensed that a single liar led the police to violate so many Black and brown kids in my neighborhood, and that the story was all over the news non-stop.

I’m no longer that angry kid. I try to help to change this city with every piece I write and with every radio and documentary appearance I make. If I allow myself to stay angry, I’ll just focus on the problems and not the solutions, and I’ll lose sight of what still needs to be done to make Boston a more equitable city.

Dart Adams is a journalist, historian, and contributor to Boston. His last story for the magazine was “The Real, Essential Backstory of ‘the Embrace’” about the Martin Luther King, Jr. statue on Boston Common. You can read more of his work here.