Inside Boston’s Psychedelic Revolution

Depression. Addiction. PTSD. Boston’s hospitals are increasingly getting behind the therapeutic benefits of psychedelic substances. What could possibly go wrong?

Illustration by Comrade

Tony wasn’t at all nervous as he drove from his home in North Andover to a retreat in New Hampshire—but his wife was. Given that Tony was on his way to ingest the powerful psychedelic ayahuasca, she feared he would come back a zombie. “That’s what we have disability insurance for,” he joked before assuring her he would not only be fine but better for it.

Ironically, it was his wife who’d led him to this retreat in the first place. Years earlier, when she announced that she was on the verge of leaving him, Tony—who by his own admission had neglected his family in his pursuit of professional success—begged his wife for a second chance. When she gave it to him, the self-proclaimed “asshole” embarked on a path of self-improvement that included trying several different traditional psychotherapies and even an anti-depressant. While those helped him begin to heal his anxiety, depression, and trauma, Tony (who asked not to use his last name to protect his privacy) knew he had more healing to do to grow into a higher version of himself. After hearing that psychedelics might be the answer, he dove deep into the research, which only encouraged him more.

The other irony was that Tony was the last person in the world anyone might expect to attend a psychedelic retreat. After all, he was a former assistant district attorney, and not just any kind: He was the chief of a narcotics task force.

After that night, though, Tony became a firm believer in the healing power of the illegal substances that, years earlier, he would have prosecuted people for using. Why? Because while he was under the influence of ayahuasca, he says, he had a life-changing experience of feeling as though he was connected to everyone in his life and with a higher power, as though there was no separation between him and the divine. “When I came back that Sunday afternoon and walked in the house,” he adds, “my wife was like, ‘Oh my God. You look completely different. You have changed.’”

Tony attended a second ayahuasca retreat in New Hampshire before learning about a psychedelic opportunity much closer to home: the Sacred Earth Sanctuary in Amesbury. As a registered church, the sanctuary has been able to take advantage of a religious exemption from the Controlled Substances Act that allows churches to legally offer psychedelics that they claim are sacraments—which in this case is psilocybin, or magic mushrooms. (Sacred Earth is the only such church in Massachusetts, but there are others around the country legally offering different psychedelics as sacraments.) Tony, who still considers himself a law-and-order kind of guy, liked the idea that he could use magic mushrooms legally, even though the federal government classifies them as Schedule 1 substances, alongside heroin and cocaine.

Illustration by Comrade

Tony’s journey into a trippy wonderland is fairly in line with what has been happening in Boston in recent years as more people increasingly experiment with magic mushrooms, MDMA (a.k.a. the party drug Ecstasy or Molly), ayahuasca, and other psychedelics. At the same time, the medical establishment—including Harvard-affiliated hospitals, as well as other research institutes in Boston—have also been experimenting, conducting research into the drugs’ therapeutic potential, including helping patients who struggle with addiction and PTSD, as well as during end-of-life care.

That research is about to bear fruit: In December, the Food and Drug Administration announced it was weighing approval of MDMA-assisted psychotherapy for the treatment of PTSD. The submission for FDA approval was filed by the Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies, or MAPS, a nonprofit founded and run by Boston’s own Rick Doblin, who has been crusading for the legalization of psychedelics for more than three decades. If the FDA approves the drug’s usage, MDMA would be the first psychedelic drug to get the government’s official nod, so long as it’s combined with therapy. (In 2019, the FDA approved esketamine, a powerful version of ketamine, for the treatment of depression. While it does have some psychedelic properties, it is technically classified as a dissociative drug.)

Questions? | Psychedelics 101 |

The Legal Alternative: Ketamine

There may be more FDA approvals to come. Psilocybin, the naturally occurring psychedelic compound found in magic mushrooms, will likely be the next to face federal scrutiny in the coming years after the FDA recently released its first draft guidance for the design of clinical trials of the drug and others like it. “We are in the midst of a renaissance of psychedelic research,” says Doblin, who wrote his Harvard Kennedy School Ph.D. dissertation on the topic more than two decades ago. “What we’re trying to do is bring psychedelics mainstream into Western culture.”

From the looks of things, Doblin’s efforts are coming to fruition. But some Bostonians, like Tony, aren’t waiting for FDA approval and are instead flocking to the Sacred Earth Sanctuary or seeking out unregulated underground ceremonies and unlicensed guides in search of a trip that they hope will help ease their trauma, addiction, or despair. The notion is so popular that the Amesbury sanctuary has temporarily shuttered in order to figure out how to handle the tsunami of inquiries. “It wants to be bigger than I can accommodate,” says Kristina Ellery, Sacred Earth’s pastor. “Because of how this is now pushing into the mainstream, it’s just been two and a half years of nonstop demand.” She is now in talks with angel investors to fund her expansion. Meanwhile, institutional investors are pouring hundreds of millions of dollars into drug companies that are hoping to ride a wave of potential profits on legalized psychedelics, a market estimated to be worth nearly $5 billion in 2022.

If all of this weren’t enough mind-warping change—particularly for the generation raised to “just say no” to drugs—there’s more. Some local activists and lawmakers believe medical usage doesn’t go nearly far enough; instead, they’re pushing for wholesale decriminalization of psychedelics for personal use in Massachusetts, despite research showing that some people who are predisposed to schizophrenia would do well to avoid these substances. Whatever your personal stance on psychedelics, one thing is for certain: If all of these changes come to pass, Bostonians are likely in for a long, strange trip.

Kristina Ellery’s Sacred Earth Sanctuary is the only religious organization in the state that has taken advantage of religious freedom laws to legally offer psychedelics as sacraments. / Photo by Pat Piasecki

When Yvan Beaussant was a medical student in France roughly a decade ago, the only time he’d heard about psychedelics was during classes about substance abuse and addiction. Then in 2015, when he was completing a residency in palliative care, he read an article about the burgeoning field of medical research into psychedelics. Almost instantly, he knew he wanted to focus his research on how these drugs could help his terminally ill patients. Dying “is such a big shift in people’s lives, and there is a need to readjust so many aspects of one’s identity,” he says, adding that he wanted to examine whether psychedelics might help patients grapple with questions related to meaning and purpose. He moved to Boston for a fellowship at Dana-Farber Cancer Institute before deciding to enroll in a certificate program through a California school for mental health and medical professionals who one day hope to work as licensed psychedelic therapists.

Today, Beaussant is an oncologist and palliative care physician at Dana-Farber, which runs a psychedelic-assisted therapy program. He is currently leading the first-ever study of psilocybin for patients in hospice care who have fewer than six months to live.

The study is still in the early stages with findings yet to be published, though anecdotal evidence is encouraging. After a single dose of psilocybin, along with professional therapy, Beaussant’s test subjects—who were experiencing feelings of hopelessness—found a deeper connection to their loved ones and renewed purpose. One 47-year-old mother, dying from progressive lung disease, was so deeply depressed that she had withdrawn from her two teenage daughters. During her mushroom trip, her existential fear of dying was eased, and the experience brought her emotionally back to life. “Her nurse kept telling us, ‘It’s like she’s not even the same person,’” Beaussant says, adding that the patient has also since reconnected with her daughters.

Other than its novelty, Beaussant’s study is significant for another reason: It is taking place at a Harvard-affiliated hospital, where research into the therapeutic effects of psychedelics first started nearly 65 years ago. Long after Native Americans ritualistically used the hallucinogen peyote and other plants with psychedelic properties, Harvard academics contributed to extremely promising psychiatric research across the country during the 1950s and 1960s, demonstrating that LSD and psilocybin, among other substances, could successfully treat a variety of maladies—from alcoholism to depression to the existential distress experienced among terminally ill patients. Tens of thousands of volunteers participated in psychedelic-assisted therapies. Even Ethel Kennedy, according to Los Angeles magazine—as well as Bill Wilson, the founder of Alcoholics Anonymous—reportedly underwent LSD therapy to treat alcoholism. Wonder drugs, they were called.

Then these substances seeped out of the research labs and into the general public, becoming synonymous with acid-dropping hippies protesting the Vietnam War, of turning on, tuning in, and dropping out. A fear campaign of misinformation—LSD scrambles your chromosomes! ’Shrooms eat holes in your brain!—ensued, and in 1970 under President Richard Nixon, the federal government reclassified LSD and psilocybin, which had been legal, as banned Schedule 1 substances with no medical value, on par with heroin. “All the research was shut down for political reasons,” says Doblin of the connection between the psychedelic counterculture and Vietnam War opposition. “Interest in psychedelics was shut down [everywhere]. It was a completely radioactive topic.”

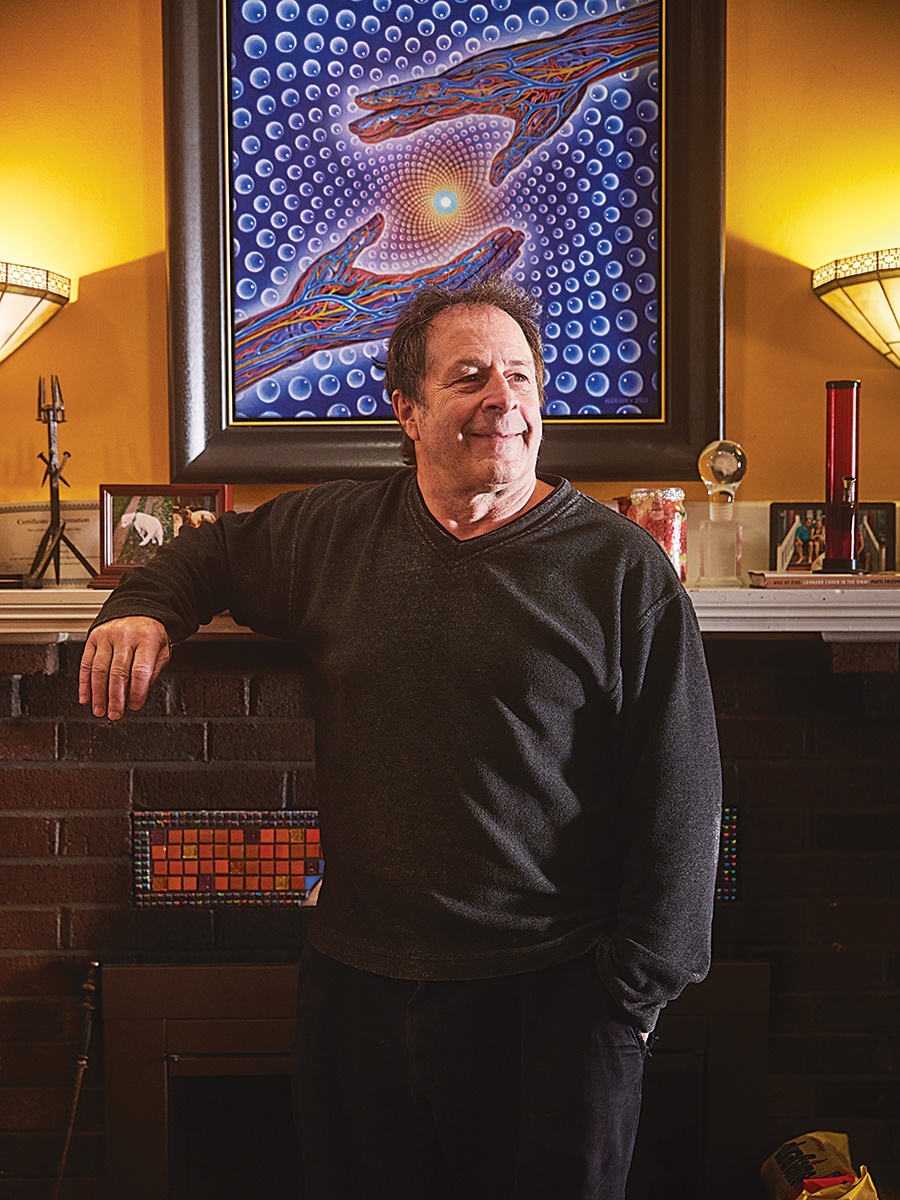

Rick Doblin, who lives in Belmont and runs a psychedelic research and education nonprofit, has been working for decades toward the moment where he is now: on the verge of getting the first FDA approval for a psychedelic drug / Photo by Pat Piasecki

The script was repeated the following decade with MDMA. From the mid-1970s through the early 1980s, researchers studied the compound as an enhancement to psychotherapy, with promising results. But once the drug leaked into broader society as Ecstasy, the feds swiftly made it illegal in 1985.

It wasn’t until the early aughts that researchers received federal approval to give psychedelics a second look. The result? In 2006, Johns Hopkins School of Medicine researcher Roland Griffiths began publishing the findings of his psilocybin research, which revealed that it could help people quit smoking after years of failed attempts, ease depression, and help terminally ill patients transcend their fear of death. He also found that 80 percent of healthy volunteers rated taking a high dose of psilocybin as one of the most spiritually meaningful experiences of their lives.

Not all of these renewed efforts to research psychedelics made it off the ground. In 2006, McLean Hospital, a Harvard affiliate, launched its first study of a psychedelic since Harvard booted the famed researcher Timothy Leary off its faculty for conducting experiments on people using LSD and other psychedelics. But researchers ran out of funding, Doblin says, before they could get the study about MDMA fully off the ground, and they never published any findings. It wasn’t until Beaussant and his team launched the hospice study currently under way at Dana-Farber that Harvard-affiliated hospitals got back in the game. And now, Dana-Farber has company: Mass General’s Center for the Neuroscience of Psychedelics, founded in 2021, is currently setting up trials to study the effects of psilocybin on irritable bowel syndrome and rumination, which is repetitive thinking or dwelling on negative thoughts and is linked to a slew of mental health issues.

Meanwhile, private donations are pouring into Boston’s universities and hospitals to fund more research on psychedelics. In August, Watertown native and Buffy the Vampire Slayer alum Eliza Dushku Palandjian, who is public about her recovery from drug and alcohol addiction, and her husband, real estate mogul Peter Palandjian, donated $7.5 million to Brigham and Women’s Hospital—a portion of which will be used to help advance the work of psychedelics in addiction treatment. (Dushku Palandjian is also finishing graduate work in counseling and clinical mental health, with a focus on psychedelic-assisted therapy.) Just two months later, a foundation run by former Tesla employee Antonio Gracias donated $16 million to Harvard to establish an interdisciplinary program called the “Study of Psychedelics in Society and Culture.” A collaboration between Harvard Law, Harvard Divinity, and the School of Arts and Sciences, it will conduct humanistic research into psychedelics.

While Harvard schools and hospitals are only just starting to reinvigorate their research into psychedelics, Doblin’s nonprofit MAPS is already close to making medical history: Based on research findings in clinical trials supporting his nonprofit’s FDA submission, Doblin believes that approval of MDMA-assisted therapy is imminent. Published in September, results of the latest phase of the trials showed that 86.5 percent of study volunteers suffering from PTSD—which included combat vets and sexual assault survivors—achieved a clinically meaningful reduction in symptoms, while more than 70 percent no longer merited a diagnosis. “We saw a lot of very, very hurt people who, under ordinary conditions, we would not expect to get better. And we had extraordinarily good results, and we have basically no side effects,” says renowned trauma expert and BU psychiatry professor Bessel van der Kolk, who was the principal investigator for the trial’s Boston study site. “I’ve done probably more outcome research than anybody else alive on trauma methods. What we saw with MDMA was really just spectacular.”

Henry, a Bostonian in his mid-thirties, was one of the study volunteers in MAPS’ clinical trials. (He asked not to use his real first name to protect his privacy.) A child-abuse survivor, he said that during his MDMA trip, his mind’s eye showed him fractionated parts of himself—one was hyper-critical, another hyper-vigilant, another shaming—and he started a dialogue, eventually coming to peace with them, and himself. On the drug, he explains, he was able to enter an area of his mind that previously had a metaphorical electric fence around it and re-experience some of his childhood trauma. “Being able to calm your amygdala and engage parts of your brain that might be kind of hidden by the strong fear response allowed me to put it where it belongs: in the past,” Henry says now. “It felt very safe to intentionally explore some of these areas that were previously kind of taboo in my mind.” Henry no longer meets the diagnostic criteria for PTSD.

Not everyone can get into a clinical trial, though. Which means locals who want to experience the effects of psychedelics right now rather than waiting around for FDA approval are increasingly seeking out alternative, illegal, and, in rare instances, potentially dangerous ways to take the substances on their own.

Anne St. Goar, a physician who worked with local participants in a MAPS drug trial for MDMA-assisted therapy, is part of the renaissance in psychedelic research underway in Boston right now. / Photo by Pat Piasecki

Massachusetts’ illegal psychedelic scene looks much different than the age-old clichés. At one recent underground meeting, there wasn’t a tie-dye shirt, lava lamp, or Indian-tapestry-as-wall-hanging in sight. Instead, six middle-aged working moms gathered in a stylish North Shore condo, nibbling on artisanal pizza and sipping herbal tea as they chatted about their recent mushroom trips.

These women are all members of a newly formed “Sisterhood,” which Susan—a former psychotherapist who asked not to use her real name because she is operating outside of the law—brought together earlier in the year to host overnight ceremonies. Every other month or so, they gather to drink a brew of ground magic mushrooms or nibble on mushroom-infused chocolate bars crafted by a Michelin-star chef while Susan guides them on their trips. They also meet once a month for so-called integration circles, in which they process their insights from taking mushrooms and work on integrating the lessons into their daily lives.

One woman, for instance, struggled to accept that her adolescent son was growing into a man—with a mustache, to boot—right in front of her eyes. She grew depressed, mourning the passage of time, but after an intense psychedelic trip, she came to peace with her emotions, understanding that all was as it should be. Afterward, she felt more present when she and her son spent time together, even during a five-minute car ride. Though she and all of the women in the group said they never set out to make changes in their lives, they’ve nonetheless noticed that since trying magic mushrooms, they have cut back on, or quit, drinking alcohol and have lost the desire to engage in unhealthy habits, including eating red meat, drinking Diet Coke, and smoking cigarettes.

Some of the women tripped in their youth and are now embracing a new relationship with the former party drug. Others never did. What they all have in common is that they are seeking something more. More than a hedonistic experience on mushrooms and much more than mommy pinot-grigio happy hours. “Alcohol is so ingrained in our culture, especially if you’re a mom,” says one woman, who thought before she began these ceremonies that she was drinking too much and has since quit altogether. “We moms get together and do psychedelics and then talk about real stuff”—hobbies, professional aspirations—“instead of just boozing and bitching about our kids or husband.”

She says that her husband, who does not partake, is happy to watch the kids if she wants to blast off on a psychedelic trip in her room for a few hours. “He benefits from it,” she says, and her whole family much prefers her as a booze-free psychonaut. “Psychedelics have put me on a journey of figuring out who I really am,” she says. “And also, being that person instead of being, like, a million different things to fit whatever situation.” One of the women illegally grows her own mushrooms and shares pictures of them with her mother (a fellow grower) on Photo Circle.

Guides like Susan—some of whom have been professionally trained—may one day staff lawful psychedelic therapy practices. For now, they are operating in the shadows, outside of the only places where psychedelics are currently legal—in clinical trials or religious organizations. According to Anne St. Goar, a therapist for the MAPS clinical trial and someone known as the fairy godmother of the local therapeutic psychedelic community, “the interest is just exponential in this work. I get calls all the time from people looking to find out how to access underground therapists, and most of them are so overwhelmed with requests they’re booking a year or two out.”

Psychedelic guides have become so popular, in fact, that they’ve started spilling over into the most rarified corners of Boston society. Recently at the elite members-only social club the ’Quin House, members could be heard comparing notes about their psychedelic guides. (If you needed proof that the psychedelic scene is no longer the provenance of acid freaks spinning in circles in parking lots outside concerts, look no further.) On one recent evening in the Reading Room, two former college buddies swapped stories. One of them is a charity-circuit regular who says he uses mushrooms for the simple joy of getting high, while the other views his psychedelic experiences as a form of “school,” in which he learns profound lessons. While he says these lessons are intensely personal and preferred not to share them, he did reveal that under the influence he came to see clearly that how he presented himself to the world was very different than how he felt inside, and it helped him learn how to bring the two into a more-healthy alignment. Both gentlemen agree, though, that consciousness-altering drugs are going mainstream, even for C-suite execs and prepsters—including one investment banker they know who was tripping at the Boston Ballet’s splashy annual black-tie gala.

None of this is to say that taking illegal psychedelics purchased on the black market is without risks. For starters, there are legal issues. “The underground is dicey,” St. Goar says. “These are Schedule 1 substances. If you get caught with them, you go to jail.”

There are also financial risks, with all sorts of opportunists getting in on the growing popularity of therapeutic psychedelics, some of them charging thousands of dollars to administer the mushrooms and accompany or guide the user during their trip. What’s more, there is no guarantee that the guide has medical or psychiatric training on the rare chance that something does go awry, especially considering the substances and the people doling them out are not regulated. “I’ve seen a huge rise in people hanging out their shingle as an expert or guru that can guide you on a trip,” says one of the gentlemen at the ’Quin. “It can just become a trend, exploited by people who take advantage of it.”

That’s pretty much what Michelle, a woman in her mid-fifties who lives in an affluent suburb west of Boston (who asked not to use her real first name to protect her privacy), feels happened to her. She had struggled with depression for decades and was tired of being on Effexor, which she had taken for 22 years. She dreamed of being pharma-free, and after watching the Netflix series How to Change Your Mind, based on journalist Michael Pollan’s book of the same name, she was excited to try psilocybin to see if it would do the trick. She searched Google for a guide, eventually paying almost $4,000 to fly someone based in Florida into Boston for the weekend. “It wasn’t bad, but I didn’t feel like it did anything,” she says. “Maybe I expected a miracle, like I could cure myself in a weekend.” Instead, she woke up one morning a month later in such a deep depression that she went straight back to traditional psychiatric meds.

Clearly, the world of underground guides can be thorny. But at least at the moment, authorities are not speaking out on the matter. The press representative for Attorney General Andrea Campbell’s office declined to comment on the subject at all. The licensing board that oversees therapists did not respond to a request for comment.

In fact, as counterintuitive as it might seem, some psychedelic advocates are less concerned about the illegal underground scene than they are about a future in which doctors and therapists are the only ones allowed to lawfully administer the drugs.

At first blush, James Davis might seem like the kind of fellow who is rooting for FDA approval of psilocybin. After all, he is a leader of Bay Staters for Natural Medicine, an organization that helps people grow magic mushrooms and other plants or fungi that have psychedelic properties. Yet he has a different take.

Davis is profoundly worried about the possibility that psychedelic pharmaceutical companies—and they are already out there waiting for FDA approval—will control these substances. And he’s worried that the regulations governing them will be written, he says, “in the interests of profit, making it really difficult for people to legally access this care at home, or in nature, where it might be most therapeutic for them.” Indeed, the cost of copays for these expensive medical interventions may put them out of reach of some people in need, to say nothing about the legions of people who are struggling and could benefit from these substances but wouldn’t meet the exact, specific diagnostic criteria to get a prescription for MDMA or mushrooms.

For these reasons, Davis and other activists believe that while pursuing FDA approval is well and good, what Massachusetts residents really need is for these substances to be decriminalized so that anyone can get their hands on them. With his organization’s help, seven cities in Massachusetts—including Cambridge and Somerville—have already decriminalized psilocybin. (Worcester has decriminalized it only for first responders and veterans.) That means these cities’ police officers don’t arrest people for possessing or using magic mushrooms.

The idea has some surprising adherents. State Representative Nicholas Boldyga—a former cop and graduate of the Western Massachusetts Police Academy, who has described himself as the “most conservative” member of the legislature—is working to make Davis’s dream a reality. “I’m the only Republican in Massachusetts talking about and promoting the benefits of plant medicines and how we can treat mental health and addiction issues,” says Boldyga, whose own family has been riddled with heroin addiction, overdoses, and alcoholism. After reading much of the research about psychedelics saving the lives of people suffering from PTSD, addiction, and depression, he was sold. “I’m passionate about it,” he says. “That’s why I filed the legislation.”

He currently has three psychedelic reform bills before the legislature, which include proposals to decriminalize the possession, cultivation, and gifting of up to 2 grams of plant-based psychedelics for adults, to legalize MDMA pending federal approval, and to set a $5,000 price cap on therapeutic access. “We know people haven’t stopped using psychedelics,” Boldyga says, adding that users should be able to consume the drugs in their own homes. “I don’t think it always needs to be tied to therapy…there are enough people that already have experience to be able to do it safely.” It is unclear if the legislation will pass, but remarkably, he says, he has received no pushback on his bills.

In fact, there has been surprisingly little negative reaction to the mainstreaming of psychedelics despite some of the obvious concerns: Will legalization mean more children can accidentally or intentionally get their hands on them, especially when they show up as colorful gummies (like cannabis)? And what happens when kids or adults have awful trips or do harmful things while under the influence?

Michael Pollan, the man bringing psychedelics to the mainstream via his bestselling book and Netflix series, doesn’t believe society is ready for wholesale legalization. As he wrote in the New York Times, there is still too much unknown about these substances, and while they are usually safe, they’re not for everyone.

Research bears this out. According to the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA), psychedelics typically don’t lead to addiction and are rarely associated with fatal overdoses. That said, in December, medical examiners determined that Friends actor Matthew Perry died from an overdose of ketamine, a dissociative drug that has psychedelic properties. A more common danger of psychedelics are hallucinations that can be terrifying in the moment. And psychedelics can be highly dangerous for some people. According to NIDA, evidence shows that these drugs can trigger schizophrenia-like illness in people who may be predisposed to it. Evidence also shows that psychedelics can be dangerous when mixed with other drugs.

MGH psychiatrist Franklin King is part of the renaissance in psychedelic research underway in Boston right now. / Photo by Pat Piasecki

Franklin King, a psychiatrist who is the director of training and education at MGH’s Center for the Neuroscience of Psychedelics, is excited about the mental health benefits of psychedelics, but he agrees that they are not risk-free. He has seen firsthand what NIDA is cautioning about: people who have their first manic episodes within weeks or months of taking LSD or mushrooms. He says that while rigorous evidence is still lacking, it is possible that these substances can unlock certain individuals’ developing schizophrenia. Still, King doesn’t believe that the risks justify keeping psychedelics out of the general public’s hands. “We need more education,” he says. “We need to figure out how to do harm reduction and identify people who are more at risk and teach the community about it, rather than saying, ‘This should be illegal.’”

It seems that the greatest risk in the renaissance of psychedelics currently under way is actually something entirely different: the current hype. Psychedelics, warn both King and Dana-Farber’s Beaussant, are neither a silver bullet nor a miracle solution to the growing mental health crisis unfolding throughout Boston and the rest of the country, no matter how much we might wish it were the case. “I absolutely believe that these substances are going to be a really momentous change for a lot of people,” King says. “I also do not think that they’re going to help everybody.”

What’s more, Beaussant says, reaping psychedelics’ full mental health benefits requires hard work, not just downing a few cups of magic-mushroom tea, lying back, and waiting to be cured. We need to use psychedelics “responsibly, with intention, commitment, respect, humility, and thoughtfulness, in institutional and social environments that are supportive of that and ensure equitable access,” Beaussant says. “It’s a long road ahead of us.”

Let’s just hope it doesn’t get too strange.

FAQs

1. So, are magic mushrooms suddenly beneficial to my health?

If you’re suffering from addiction, depression, PTSD, or anxiety, they might be. Local medical institutions are currently studying the effects of the drug—as well as several others—on many mental and physical health conditions.

2. This can’t be legal…can it?

Not yet, though FDA approval may be imminent for MDMA-assisted psychotherapy, with psilocybin (a.k.a. magic mushrooms) potentially up next. Some lawmakers and activists are pushing for decriminalization or full legalization. In the meantime, ketamine, a dissociative drug that has some psychedelic properties, is legally available as a treatment for depression and can be accessed at several clinics across the state (see page 90 for more).

3. Are psychedelics addictive? And can I overdose?

While psychedelics generally aren’t considered addictive, users can build up a tolerance over time, and they’re not without risks. While for many people, psychedelics produce positive feelings, for others, they can create fear and anxiety that lead to unsafe behavior. The more you take, the more risks there are. When purchased on the black market, the drugs can also potentially be contaminated with dangerous (and highly addictive) substances like fentanyl.

4. What are my options if I want to try it?

If you want to remain above board, your best bet is to inquire with local hospitals about clinical trials. Because psychedelics are still illegal, some locals have opted to join underground group therapy or hire an unlicensed guide.

5. If I hire a guide, what will he do, and how will he help me?

Guides, a.k.a. “trip sitters,” stay with their clients while they’re under the influence of psychedelics to both minimize risks and make sure their experience is meaningful and safe.

6. What’s all the buzz about microdosing? Is that the same as therapeutic treatment?

Microdosing involves taking a small amount of LSD or psilocybin to reap some of the benefits of psychedelics—including improved mood and an increase in creativity—without the accompanying hallucinations. Studies on the effectiveness of microdosing, however, have so far been mixed.

The Legal Alternative: Ketamine

Ketamine is often referred to as the only legal psychedelic, but it isn’t really a psychedelic. While it does have some hallucinogenic effects, it is a so-called dissociative anesthetic that doctors and veterinarians have used since the 1970s as a short-acting pain reliever.

In the 1990s, it became a popular party drug known as Special K. Along the way, researchers found that it worked wonders combatting depression. By 2010, doctors had started prescribing it “off-label,” administering it by injection or IV drip for depression. Then in 2019, the FDA approved Spravato—a nasal spray made from eskatamine, which is a more-potent version of ketamine—for treatment-resistant depression when used in conjunction with a conventional antidepressant.

Today, there are many ways to access ketamine: You can get a prescription from your doctor for Spravato; receive an injection from a psychiatrist or other medical doctor; or have oral ketamine lozenges delivered by mail from an online company after its staff doctors evaluate you. Alternatively, you can visit one of the many ketamine clinics sprouting up around the state, where you will be evaluated for a prescription and then given an IV drip or injection. It’s important to note that while some of these clinics are staffed with mental health professionals and offer psychotherapy along with the drug, others are staffed by anesthesiologists with no mental health training. Here are four locations in Greater Boston.

Cambridge Biotherapies

With three locations, these clinics offer both a straight-up ketamine infusion treatment and ketamine-assisted psychotherapy (KAP) to treat everything from addiction and depression to OCD and PTSD. At the cozy spaces, including a charming Victorian in Cambridge, you’ll also find support sessions if you prefer something more akin to coaching than full-on psychotherapy.

Cambridge, Amherst, and Beverly, cambridgebiotherapies.com.

Boston MindCare

Offering IV infusions, oral ketamine, nasal ketamine, and intramuscular ketamine injections, MindCare calls itself Metro Boston’s most experienced ketamine practice. Here, patients receive direct care from experienced anesthesiologists, though the practice does not offer psychotherapy.

Lexington, bostonmindcare.com.

Psych Garden

This clinic only administers ketamine along with intensive psychotherapy in its treatment rooms, which are appointed with comfy couches and scented candles. The clinic, which also offers couples and family therapy as well as addiction treatment, is planning for the future, poised to offer MDMA, psilocybin, ibogaine, and other medications if and when they get FDA approved.

Belmont, psychgarden.com.

Ketamine Greater Boston

This clinic offers ketamine-infusion therapy to treat patients with severe depression and bipolar disorder and requires a referral from a licensed mental healthcare professional. Check out the thorough FAQs on its website, which address who should avoid ketamine as well as what drugs are contraindicated with ketamine.

Needham, ketaminegreaterboston.com.

Psychedelics 101

These days, hallucinogens aren’t just for trippy hippies; they’re being studied by researchers near and far as legitimate cures to all manner of ailments.

SUBSTANCE: Psilocybin

ALSO KNOWN AS: ’Shrooms, Magic Mushrooms, Mushies, Boomers, Tea Party

WHAT IT IS: A naturally occurring psychedelic chemical compound produced by more than 200 species of fungi.

RESEARCH AREAS: Nicotine and alcohol dependence, obsessive-compulsive disorder, cluster headaches, PTSD, depression, anxiety disorders, eating disorders, cancer-related existential distress.

RESEARCH STATUS: The FDA has granted it a “breakthrough therapy”

designation to streamline the path to an eventual drug approval.

SUBSTANCE: MDMA

ALSO KNOWN AS: XTC, Ecstasy, Molly, Candy, Disco Biscuits, Vitamin E

WHAT IT IS: A potent empathogenic drug with minor psychedelic properties.

RESEARCH AREAS: PTSD, eating disorders, alcohol dependence, depression.

RESEARCH STATUS: At presstime, the FDA was weighing approval of the drug to treat PTSD in conjunction with therapy.

SUBSTANCE: LSD

ALSO KNOWN AS: Acid, Lucy, Looney Tunes

WHAT IT IS: A potent psychedelic synthesized from a substance found in ergot fungus.

RESEARCH AREAS: Alcohol dependence, pain and cluster headache relief, anxiety, depression, psychosomatic diseases, PTSD.

RESEARCH STATUS: Ongoing clinical trials.

SUBSTANCE: Ibogaine

ALSO KNOWN AS: Endabuse

WHAT IT IS: A psychoactive substance found in the roots of the iboga plant, which is native to central Africa, with psychedelic and dissociative properties.

RESEARCH AREAS: Addiction, depression, pain.

RESEARCH STATUS: Ongoing clinical trials.

SUBSTANCE: DMT/Ayahuasca

ALSO KNOWN AS: Aya, Hoasca, Yagé

WHAT IT IS: An ancient South American psychedelic brew traditionally made from two plants, one of which contains dimethyltryptamine (DMT), a powerful psychedelic. DMT can also be taken on its own.

RESEARCH AREAS: Eating disorders, addiction, depression, PTSD, OCD.

RESEARCH STATUS: Ongoing clinical trials.

From left, Top Doctors Jessica Allegretti of Brigham and Women’s, Ali Raja of Mass General, and Ashtar Chami of Tufts Medical Center. / Photograph by Ken Richardson

First published in the print edition of the February 2024 issue with the headline, “Take Two Magic Mushrooms and Call Me in the Morning.”