The George Hamilton Cold Case: How to Get Away With Murder

For nearly 50 years, the truth about who shot a high-profile furniture salesman has been one of Boston’s most lasting mysteries. Why the killing of George Hamilton remains unsolved.

Illustration by Benjamen Purvis

Jolted awake by the sound of someone frantically ringing the doorbell, the young woman begged her husband not to answer the door.

It was around 3 a.m. on April 25, 1976, and Carol Hamilton had spent an unassuming night out with her family. In the early evening, she ate dinner at South Pacific, a Chinese restaurant in Newton, with her husband, George, and their two adopted children, Stephen and Sharon. Under an overcast sky, they’d driven to the Hanover Mall to see the Mel Brooks picture Blazing Saddles, and afterward, along rain-slicked roads, George had whisked them back home to snoozy Canton. Carol went to bed shortly after tucking in the children while George took a phone call downstairs.

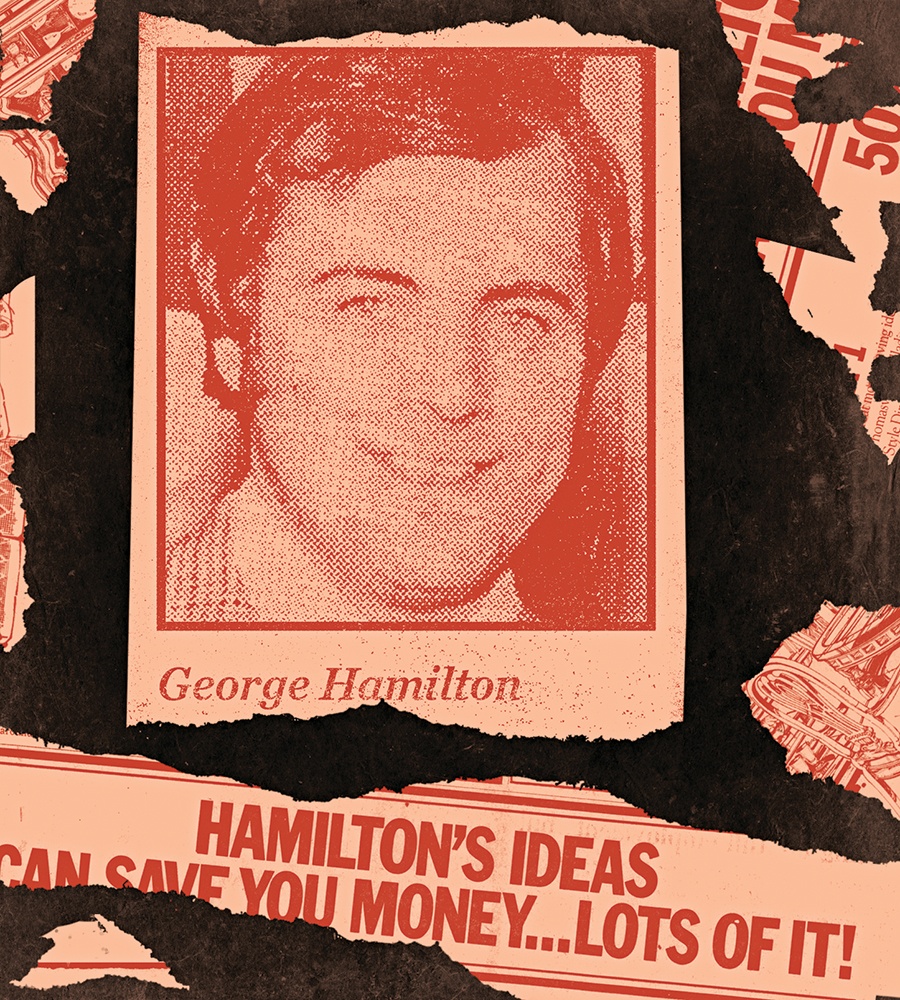

The couple’s life together had not been without its challenges, but they were just beginning to hit their stride. Dashing and driven, 33-year-old George was a self-made executive from Mattapan. In just a decade, he had enjoyed a meteoric rise from Christmas-rush salesman at Jordan Marsh to the president of what was once described in these pages as “perhaps the most beautiful furniture store in America.” In the fall of 1974, he’d launched a sprawling $3 million superstore with his name in lights: Hamilton’s. When it opened, accompanied by a chic advertising blitz in the Boston Globe, the store was an immediate sensation. Its dazzling showrooms seemed plucked from the pages of a glossy home and garden magazine. When shoppers got tired of browsing, the premises offered a stylish Parisian café, an art gallery, a gift shop, a lecture hall—even a nursery providing free childcare.

Hamilton’s was just slightly ahead of its time. In those days, most families shopped for furniture at a department store, picked their couch out of a sample book, put down a deposit, and waited weeks or months for it to arrive. At Hamilton’s, if you saw something on the floor—from sofas and nightstands to rugs and picture frames—you could take it with you or have it delivered in a few days. Just a few years later, chains such as Jordan’s and Ikea used a similar blueprint to build regional and global empires.

Though Carol was proud of her husband’s business, by that fateful night in April—when someone came over to lean on their door buzzer—Carol knew something few others did: George’s vision had been both wildly successful and, somehow, a miserable failure.

In its first year, Hamilton’s sold more than $9 million in furniture—yet lost money. By the spring of 1976, the company was more than $1 million in the red, and Carol’s husband had been quietly pushed out by the company’s board of directors.

That was a problem for the Hamiltons because even though George had been the company’s founder, visionary, and president, he owned almost none of the enterprise that bore his name. The Hamiltons’ home in Canton wasn’t a mansion—it was a split-level house at the end of a dead-end street. In fact, the Hamiltons were in deep financial trouble. What many people didn’t realize about Carol’s husband was that George had launched all of this—the store, the café, the daycare, the advertising—with other people’s money.

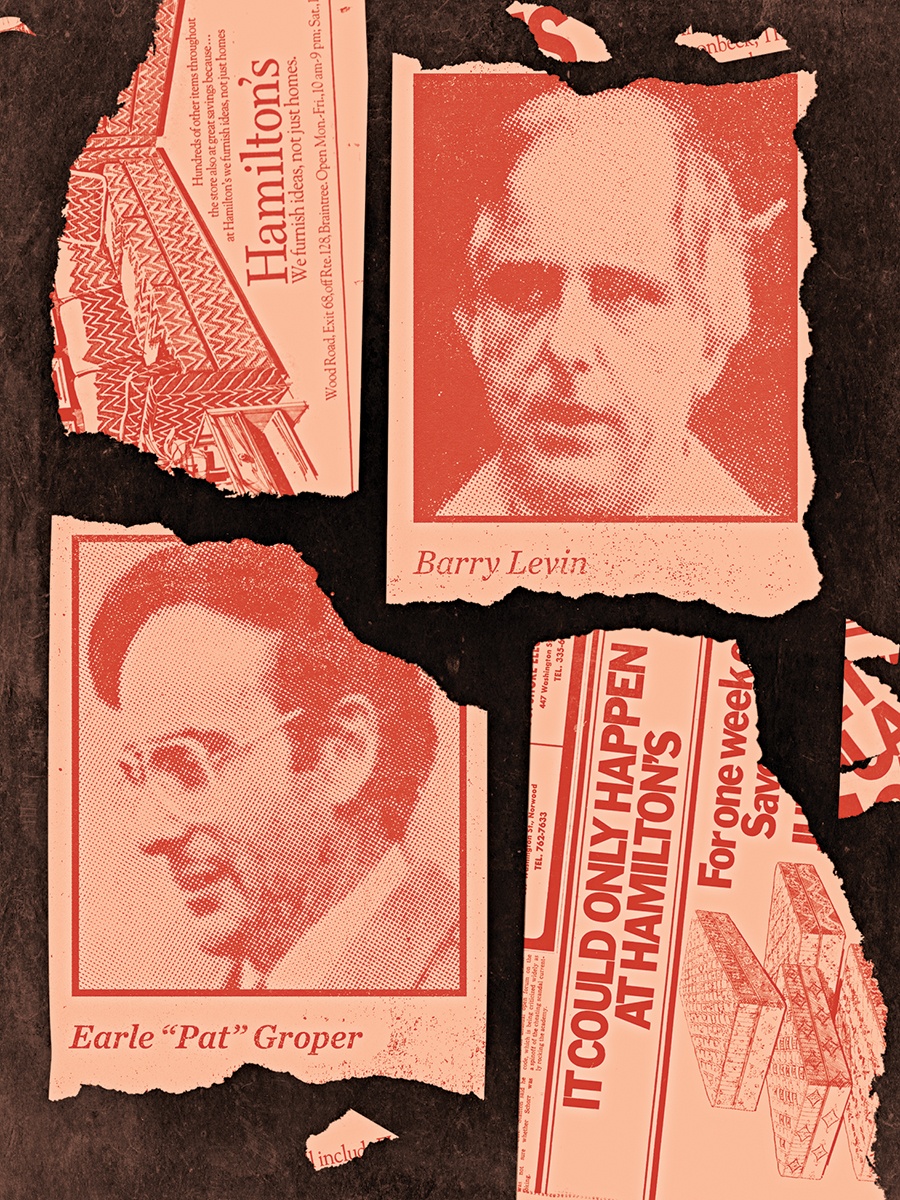

The lead investor in Hamilton’s was Earle “Pat” Groper, a man of deep pockets and impeccable credentials. Harvard-educated and on a host of civic and philanthropic boards, he boasted access to the city’s best lawyers—Hale & Dorr—as well as financing from the Boston-based bank U.S. Trust Company, whose president, James Sidell, lived on the same Newton cul-de-sac as him. Groper, who was on the bank’s board of directors, also came with his own money: He was a direct descendent of a legendary Canadian clan, the Bronfmans, who’d made a fortune during Prohibition by supplying American bootleggers with booze from warehouses located just north of the U.S. border. Later, after Prohibition ended in the United States, the Bronfmans moved their operation south to New York and invented the modern spirits industry, raking in billions from the Seagrams family of brands.

Yet Groper’s family hadn’t always had it easy. Before he was born, his mother’s first husband was murdered during a fatal encounter with rum runners. A few years later, now a widow with two young daughters, Groper’s mother, Jean, remarried and settled the family into a massive mansion in Brookline staffed by a half-dozen servants. That’s where Earle Groper grew up: in New England luxury. After law school at Boston University, Groper took over his family’s wholesale liquor business but seemed restless to chart his own path. He invested in a handful of other companies, often with his longtime friend Barry Levin. Groper’s brother-in-law happened to be doing well in the furniture business and introduced Groper to an up-and-comer named George Hamilton, and together with Levin, he decided to go all in on Hamilton’s.

For a while, Groper and Hamilton seemed perfectly matched: Groper knew nothing about furniture and was content to let Hamilton lead. But soon they started to bring out the worst in each other—Groper, distant and entitled, clashed with Hamilton, who was self-made and stubborn. And Groper’s supposedly deep pockets came up short: Despite record sales, the business was constantly low on cash. Then in March 1976, without warning, Groper and Levin announced their plans to sell the business, and George was out. Which just might help explain what happened on that stormy early morning of April 25, 1976.

Ignoring Carol’s frantic pleas to call the police, George pulled on a pair of peach slacks and padded downstairs to see who could be ringing his doorbell at this odd hour. She stayed upstairs, in the hallway by the phone, listening.

After the front door opened, Carol heard a man’s voice say something like, “Is Mary here?” George said there was no one in the house with that name. There were some muffled words before she heard George say, “No, no,” followed by five loud bangs and the screech of car tires peeling away. Then the night turned quiet and still.

She grabbed the phone and called the police before she ran to her children’s room. Her husband lay shot just inside the doorway.

Nearly half a century later, the identity of the man who shot and killed George Hamilton in his Canton doorway is still, officially, a mystery. The Norfolk County District Attorney’s office has kept the case open all this time. But when I began asking about the Hamilton murder in the fall of 2022, I discovered that “open” doesn’t necessarily mean “unsolved.” “Oh, we know who did it,” one former Norfolk County District Attorney’s office employee told me.

The person he described matched someone I’d heard about before. And it begged a question: If investigators know who murdered Hamilton, why hasn’t the case been closed?

The answer might be simple: The former DA’s office employee told me the reason their prime suspect has never been prosecuted was that this person was already on death row in Florida for another murder. Yet for reasons that will become apparent, I wondered whether there was a different explanation for why the case had remained open for so long—a reason that involved long-held secrets about the connections between law enforcement and organized crime, and between Boston’s business elites and its highest-ranking government officials.

Searching for Hamilton’s killer led me on a tour of Boston’s other history: back to buried tales of money, greed, corruption, and power. Time swallows up details and information, but this story was largely based on fresh interviews, court documents, and contemporaneous reporting from both this magazine and Boston newspapers. When I went looking for Hamilton’s assassin, I was pretty sure the people responsible were already dead. What I was really looking for was the answer to another question: How much influence does it take to get away with murder?

Searching for Hamilton’s killer led me on a tour of Boston’s other history: back to buried tales of money, greed, corruption, and power.

Illustration by Benjamen Purvis / Photo via the Hamilton family/Courtesy of Jonathan Lang

When I began digging into the Hamilton murder, the first person I reached out to was John Kivlan, a retired assistant DA from the Norfolk County District Attorney’s office, who knew more about the murder investigation than anyone. Kivlan, according to one of his colleagues, had never stopped trying to gather evidence to indict Hamilton’s killer. When I reached him by phone, Kivlan told me he’d be willing to talk to me, with one rather large caveat: Because the case was still open, he’d need permission from the current DA’s office—which was unlikely unless the case could be closed. I didn’t know it then, but he’d said the same thing to Hamilton’s family as recently as 2018.

Unfortunately, that first time I spoke to Kivlan, in the fall of 2022, would also be the last: A few months later, in January, he was killed in a single-car highway accident. After his funeral, I reached out to several of his former colleagues, who described Kivlan as a tough-as-nails prosecutor, every bit the ex-Marine, who’d taken on some of the most prestigious, well-funded defense lawyers in the country—and won. In the 1970s, then–Norfolk County District Attorney William Delahunt recruited Kivlan to head up his white-collar-crime unit. One evening in 1985, a coworker convinced Kivlan to buy his very first lottery ticket, and he won $2.7 million, then showed up the next day as if nothing had happened and kept working.

Although Kivlan played his cards close to the vest when it came to the Hamilton murder, he did give me one on-the-record statement: “You can say that the case was thoroughly investigated,” he said, which I took to mean that he was certain of who the killer or killers were. He also told me that if I wanted to know what really happened, I should read the records of the fraud trial.

The fraud trial: It was the closest anyone ever came to trying the Hamilton case, though the charge of murder was nowhere to be found in the 31-count indictment handed down in July 1978 against Groper and Levin and two others involved. Delahunt told reporters he believed a contract had been taken out on Hamilton’s life but that “it would be inappropriate for me to comment” on any connection between the fraud case and the homicide. At the time, it was the most expensive white-collar-crime case ever brought in Massachusetts. And for many involved, it came with costs that couldn’t be calculated on a balance sheet—costs that would be felt for years and decades afterward.

From the moment police found Hamilton dead in his doorway, the case seemed like a stone-cold whodunit. Newspaper reporters hinted that detectives were looking into Hamilton’s personal life, but when the cops asked around, they found that Hamilton was churchgoing, hard-working—boring. He’d told friends he was having trouble at work—the investors in Hamilton’s had pushed him out, and he was looking for a new job. Hamilton told one friend he was having money problems. Still, investigators found Hamilton’s debt was all above board—his loans were with banks, not leg-breakers. Before long, though, investigators believed they’d found a motive: money, and lots of it.

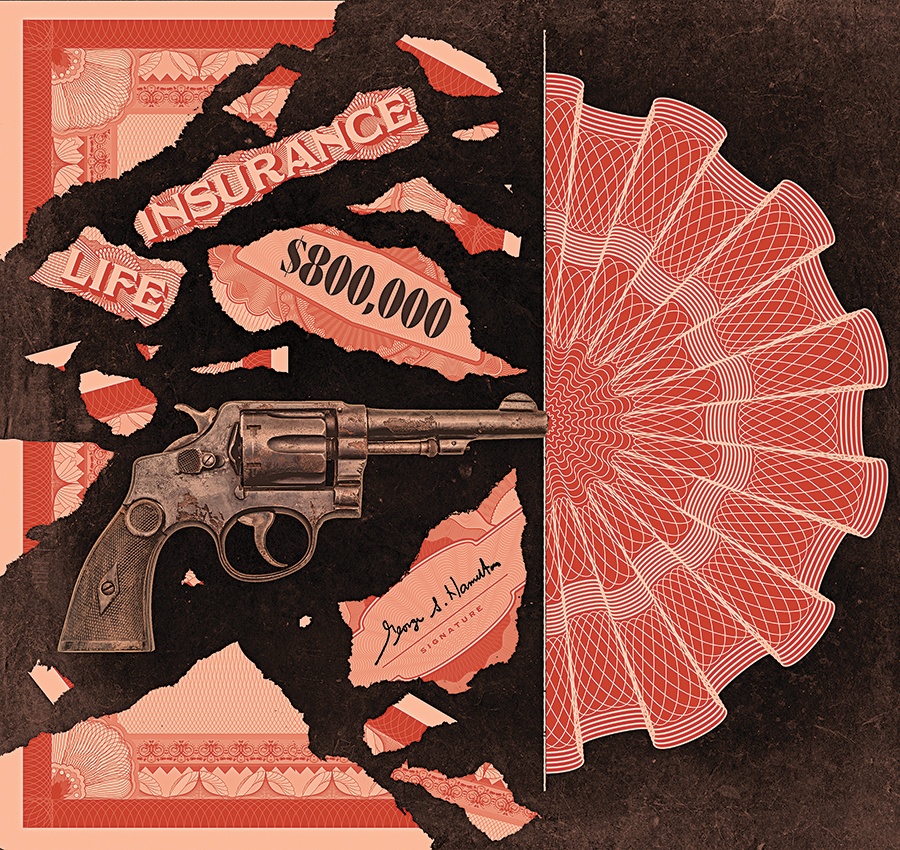

Police discovered there had been an unusually large life insurance policy taken out on George Hamilton. Two policies, actually. The first was for a million dollars and, on its face, didn’t register as suspicious.

When Hamilton’s furniture store was founded, Groper and Levin had taken out routine “key-man” insurance on their president: After all, it was George Hamilton’s leadership that elevated the store—his vision, his name on the shingle. If, God forbid, the man got hit by a bus, they needed something to secure their investment. Nobody batted an eye.

It was the second policy on Hamilton’s life—for an additional $800,000—that drew investigators’ attention. For one thing, this secondary policy had been put into effect mere weeks before Hamilton’s death, at a point when the investors were actively trying to replace their president. More to the point, the second policy had been forged. The signature on the form was not Hamilton’s; eventually, an insurance agent and a doctor admitted they’d forged the insurance application and the physical exam as a favor to Levin. In both policies, the primary beneficiary of the nearly $2 million in total life insurance money wasn’t Hamilton’s family. The majority of the money was destined for Hamilton’s investors—mainly to Groper and Levin and the debt they’d incurred to U.S. Trust.

At the fraud trial against Groper and Levin, prosecutor Kivlan used forensic accounting to meticulously piece together an ominous timeline. Undercapitalized from the start, the furniture business couldn’t keep up with demand. By 1976, Hamilton’s desperately needed an infusion of cash to avoid bankruptcy. Tensions were high, and the business bifurcated into two camps: George Hamilton began seeking new financing to buy out Groper and Levin. Groper and Levin, meanwhile, began quietly looking for a new president.

The investors’ clumsy efforts soon got back to Hamilton, who took the news badly. Employees reported hearing shouting matches. Eventually, in March 1976, there was a fateful board meeting: The board approved Groper and Levin’s plans to sell the company to a rival called Scandinavian Design. Hamilton was asked to resign, but he refused: Quitting would trigger a non-compete clause in his contract, but if they fired him, he’d be free to pursue a new enterprise. He left the building and never returned. Although the deal had not yet taken effect, Scandinavian Design sent one of its vice presidents to oversee operations, and Levin and Groper took Hamilton off the payroll. He was out.

What Hamilton didn’t know was that Groper and Levin had secretly taken out that second life insurance policy on him. At first, the insurance companies balked—noting the $1 million key-man insurance policy already on the books, they believed the business was already well insured. Levin asked his insurance broker to find another company to place the insurance with. They eventually settled on Charter National out of St. Louis, which specialized in “substandard risk” cases. After he learned that Groper and Levin were interviewing new CEOs, Hamilton refused to cooperate with the insurance application, and rather than abandoning the idea, Levin secretly pressed on. His insurance broker completed the forms, and a doctor forged the physical.

Once Hamilton had left the company, though, the policy got more complicated: Levin had tendered only a $500 “binder”—a down payment on the premium. The company was strapped for cash, but unless it paid the remainder of what it owed on the policy—about $2,500—the coverage would expire in early May. But in early April, when Levin approached the company’s new owners for authorization to pay the balance, he was rejected. The new bosses understandably wondered why Levin would want to keep a life insurance policy on an executive who’d been removed from the payroll, and ordered him to terminate it. The clock was now ticking. Another board meeting had been scheduled for April 23 to officially consummate the sale of the company and make a decision on Hamilton’s potential dismissal, but the day before the meeting, Levin canceled and rescheduled for May 3: The day the insurance policy was to expire.

In April 1976, Hamilton was—to his investors—worth more dead than alive. And he was worth significantly more if he died on schedule—that is, before the insurance policy expired the first week of May.

He was shot and killed on the morning of the last Sunday in April.

Illustration by Benjamen Purvis / Photos courtesy of the Boston Globe

Hamilton wasn’t the only one under pressure at the time. Among the witnesses who testified at the fraud trial was Thomas Hannaford, who was on Hamilton’s board of directors as a representative of his family’s real estate company, C. Healy, which held the lease on Hamilton’s Braintree location. Hannaford had been friendly with Hamilton and, at one point, tried to secure alternative financing to allow Hamilton to buy out Groper and Levin. I cold-called him one morning not long ago, and the trial still seemed fresh in his mind. “My opinions on the matter? His partners killed him for the insurance money,” he told me. When Hamilton was murdered, Hannaford thought he and his stepfather might be next—they went into hiding. “It seemed clear it was either Barry Levin or Pat Groper behind it. They were the only two with any vested interest, and the interest was the insurance policy.”

During the six-week fraud trial, prosecutor Kivlan faced off against an all-star legal defense team, including former Richard Nixon attorney James St. Clair for Groper. Kivlan also went head-to-head with additional lawyers from Hale & Dorr, who were called to testify about the company’s financial matters and the key-man insurance policy. The jury deliberated for 20 hours over four days. On March 5, 1979, the verdicts came back: Groper and Levin were guilty of fraud, forgery, and larceny. They faced up to 24 years in prison.

Then the levers of power began to move against the wheels of justice.

In the week between the verdict and sentencing, legendary Globe political columnist David Farrell wrote about the Hamilton case, heaping praise upon the DA’s office for having prosecuted Levin and Groper “in the face of enormous pressures from influential friends, business associates, and acquaintances”—a campaign he called “so intense that it appears to be orchestrated.”

The “massive pressures” to drop or settle the case, Farrell wrote, “were exerted primarily by Groper’s admirers” and focused first on Norfolk DA William Delahunt. When that didn’t work, state Attorney General Francis X. Bellotti was approached to lean on Delahunt, his protégé and friend. “Bellotti, to his credit, would have nothing to do with such feelers,” Farrell wrote. But the campaign didn’t stop there. Farrell reported that the Superior Court judge in the case—John Irwin—“is being exhorted by many influential people to be lenient.” The next day, Groper and Levin were sentenced to six to eight years in prison. (The insurance agent who forged Hamilton’s signatures on the policy was also found guilty and received a sentence of three years; the doctor who helped him received three months.)

Farrell never identified who, exactly, was allegedly putting pressure on two high-ranking prosecutors and a Superior Court judge. But four days after Groper and Levin were sentenced, a Delahunt aide leaked to the Globe that Massachusetts Governor Ed King’s administration had slashed a line item in the state budget that “wipe[d] out” Delahunt’s white-collar-corruption unit—the very unit, headed by Kivlan and a former FBI agent, that had investigated and prosecuted the Hamilton insurance fraud case.

It was a sign of things to come. Groper and Levin were out of jail in less than a month.

On May 10, the two furniture store investors were freed, pending an appeal of their conviction. It was their third attempt, having been denied by two separate courts. The duo finally found sympathy from a three-judge panel of the appeals court; their appeal wouldn’t be heard for another two years.

In February 1981, a judge overturned the convictions on a technicality: The jury, the judge said, had been “irreparably prejudiced” by Kivlan’s mention of Hamilton’s murder, against the instructions of the trial judge. Groper, Levin, and the two other defendants were granted a new trial.

By the time Delahunt’s office retried the fraud cases against Groper and Levin in 1985, the winds had shifted. Kivlan, the DA’s star prosecutor, was no longer on the case. Instead, it fell to a young assistant DA named Judith Cowin.

When I spoke to her early last year, Cowin had retired as a judge from the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court a decade prior. The way she came to prosecute the second trial was unusual in a few ways. First, it was odd that Kivlan hadn’t taken the case himself—it was a high-profile prosecution, and by all accounts, he could’ve run rings around the defense. Second, Cowin recalled the case was given to her by Delahunt directly; case assignments usually came from an assistant DA. And third, when I asked her if Kivlan had assisted her, she said no: She’d relied on the voluminous court record of the first trial and the lengthy grand jury hearings that preceded it.

Cowin recalled that she, too, went up against James St. Clair, who was back arguing for Groper, and Levin’s lawyer Nancy Gertner, who went on to become an esteemed federal district court judge. Cowin was adamant that she knew absolutely nothing about the Hamilton murder case and had focused entirely on the fraud allegations. I found that odd because she and others told me how close-knit the DA’s office was. (Up until COVID struck, Cowin, Kivlan, and others from the office still met regularly for lunch, as they had for decades, Cowin told me.) Another colleague of Cowin’s—someone who’d given me her phone number, actually—had been the person who told me, “Oh, we know who did it.” The “we” in that was a group I understood as probably including Cowin.

Eventually, I asked her: When you tried Groper and Levin in that second trial, did you expect to win? And then there was a long, long pause on the other end of the line.

Today, George Hamilton’s family members recall Kivlan fondly—they believe he fought hard for a conviction. They do not have the same memories of Cowin. “I just felt, This is way out of her league,” Hamilton’s sister, Phyllis Lang, told me. Another family member who didn’t want to be named said they “did not have a good feeling about her.”

The feeling proved to be justified. Groper and Levin waived their right to a jury trial, and on June 6, 1985, they were acquitted of all charges. “For nine years it’s been a nightmare,” Groper told the Boston Globe the day after the acquittal. “I’m thankful to the good Lord it’s over.” Gertner, Levin’s lawyer, told reporters that her client had been targeted by the DA’s office because the prosecutors couldn’t land the homicide investigation. “They were casting around for someone to take it out on,” she told the Globe.

No further charges were ever brought against Groper or Levin. (The insurance broker and the doctor who helped execute the scheme pleaded guilty just before the start of the second trial.) But not for lack of trying. Decades later, one of Kivlan’s colleagues—an assistant DA named Matt Connolly—began blogging about his experiences in law enforcement. In one post, he mentioned that he and Kivlan had once gone to interview a man named John Sweet. “Kivlan was interested in finding out more about the murder of George Hamilton,” he wrote, “having prosecuted those who we believed set up Hamilton’s murder”—i.e., Groper and Levin. They quickly realized Sweet was a con man; he was a drug dealer, pimp, arsonist, bookie, and an admitted perjurer who’d twice beaten a murder rap in Florida for allegedly hiring two men to kill his girlfriend’s millionaire husband. In fact, Sweet was so slick that after twice beating the murder charge, he’d turned around and become a state witness against one of the hitmen he’d hired—a Winter Hill Gang enforcer, hijacker, and drug dealer named Billy Kelley. After several trials, Kelley was convicted and sentenced to death in Florida. When Kivlan’s colleague told me, “Oh, we know who did it,” that’s who he was talking about—the guy who was on death row.

The DA’s office never believed that Groper and Levin had pulled the trigger themselves. Prosecutors assumed the pair had hired a guy for the job. And somewhere along the line, Kivlan had decided the hitman was Kelley. It wasn’t hard to see why: Kelley hung around with some of Boston’s most notorious bad men; he was once sought in connection with a car bombing that killed the wife of a state witness. “Kivlan never let up in his pursuit of trying to get the evidence against Billy Kelley,” Connolly wrote on his blog. (Connolly died in October 2021.)

There was just one problem: If Kivlan really was chasing Kelley, he was almost certainly chasing the wrong man.

The identity of George Hamilton’s murderer has been an open secret in some law enforcement circles for at least 40 years.

In January 1983, the FBI received information about the Hamilton case from one of its most prized and highly protected informants, Boston crime boss Stephen “The Rifleman” Flemmi. Back then, Flemmi told the FBI that a corrupt Boston police detective named William Stuart had committed the murder. But the FBI never passed that information along to any state agencies—the report stayed locked in the FBI’s file cabinets until after the mobster James “Whitey” Bulger was captured.

Then again in 2003—under very different circumstances—Flemmi told Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) investigators that Stuart had confessed to being the shooter in the Hamilton murder. In ’83, Flemmi had been a top-secret informant; in 2003, he was singing for his life. Facing a host of charges that could’ve included a death sentence, Flemmi spilled his guts in a 146-page criminal debriefing that covered decades of old crimes. He was under great pains to be accurate; if the government discovered he was lying, they could revoke his plea bargain. In it, he again recounted Stuart’s confession to the Hamilton killing. He told DEA agents that Stuart had been driven to Hamilton’s house by a longtime Flemmi associate. Flemmi thought Stuart might have got the murder weapon from yet another Flemmi partner, the future La Cosa Nostra boss “Cadillac” Frank Salemme, who Flemmi told the DEA had given Stuart a cache of guns to hold while he was in prison.

Who was William Stuart? That’s one of the great untold sagas in Boston’s dark history of collaboration between law enforcement and organized crime. In the 1960s, Stuart rose rapidly through the detective’s division at BPD as an intelligence officer. His job was to keep tabs on prominent thugs and develop criminal informants—among whom were sibling Roxbury gang bosses Walter and “Wimpy” Bennett and their protégé, a handsome young hood named Stephen Flemmi.

Working from a playbook that the FBI would later copy, Stuart protected the Bennetts in exchange for inside information about their criminal rivals. His protection of Flemmi went even further: According to confidential police records, in September 1964, Stuart saved the lives of both Flemmi and his hitman brother Vincent “Jimmy the Bear” Flemmi; the Bear had just whacked a thug named Leo Lowry, and Lowry’s pal—a Roxbury man named William McCarthy—was about to gun down both Flemmi and Vincent when Stuart intervened at gunpoint. Records state that, according to Flemmi, Stuart was also on the gang’s payroll and had once tried to set up a rival gangster for Flemmi’s gang to assassinate. This fluidity of allegiance was not an uncommon arrangement: Not long before, Boston had been described by one scholar of crime as the most corrupt city in the most corrupt state in the country.

Flemmi eventually had a hand in eliminating both Walter and Wimpy, as well as a third Bennett brother, Billy. Unlike the first two, the Billy Bennett hit went sideways, and Flemmi was forced to call in a favor—from Stuart, who arrived shortly after the murder to help Flemmi clean up the crime scene, according to Flemmi’s DEA criminal debriefing. By the time indictments came down in Billy Bennett’s murder, Flemmi had a new protector: Stuart’s close friend, the infamous FBI agent H. Paul Rico. And Rico, who was by then running Flemmi as a top-secret FBI informant, helped Flemmi evade capture by tipping him off about an incoming indictment against him for Billy Bennett’s murder, the debriefing states. Stuart was not so lucky. One of Flemmi’s coconspirators in the hit turned state’s evidence and fingered Stuart, who was indicted as an accessory to murder after the fact.

Following a sensational trial in April 1970, Stuart beat the murder rap and went right back to the BPD. He was then demoted from detective to patrolman after speaking to television reporters about an unrelated trial, and he retired a few years later.

At that point, Stuart’s life started to go in a different direction. After leaving the force, he took a job as a security consultant at Branded Liquors—Earle Groper’s family wholesaling business. When Groper went into business with George Hamilton, Stuart went along to become Hamilton’s security consultant. Some of the Hamilton’s folks were suspicious of him from the outset. “He didn’t seem to know anything about the alarm system or whether the gates were locked at a certain time,” recalls Thomas Hannaford, who was on Hamilton’s board of directors. “I don’t know what kind of security he was. Conventional security concerns didn’t seem to be his actual job.”

Hamilton’s family remembers Stuart as well. In the weeks leading up to George’s murder, the family received a series of strange phone calls. Sometimes, the person on the other end would purport to be someone they knew—but the voice sounded off. One month before the shooting, Hamilton was called by a man who said he needed to speak with him urgently, and a meeting was arranged at a nearby restaurant. The caller asked for the make and model of Hamilton’s car and told him to wait in the vehicle until he was approached. Instead, Hamilton called a friend to keep watch on him, then took his wife’s car and stood under the marquee while a white Cadillac with at least two men inside circled past multiple times and then left. If, shortly after the murder, you’d asked Hamilton’s family who killed him, they’d have likely told you Bill Stuart. They’d suspected him of being behind the phone calls and maybe even being the sicko who’d poisoned one of Hamilton’s prize collies.

In 2013, Boston Herald columnist Howie Carr published a heavily redacted version of Flemmi’s DEA confession as a book called Rifleman. The section on the Hamilton murder made clear that Stuart had been the killer, but key names and sentences were blacked out. Flemmi relayed that Hamilton was “murdered as a favor by Bill Stuart for [redacted].” When I read Carr’s book, I assumed the blacked-out name must’ve been Groper or Levin. It seemed like the obvious answer. But when I obtained an unredacted copy of Flemmi’s DEA debriefing, I was shocked to find the name Flemmi had given—the one identifying the person for whom Stuart had done the favor of committing the murder—was neither Groper nor Levin.

What’s more, Flemmi also mentioned that he had told his old FBI handler, Agent John Connolly, about Stuart’s role in the Hamilton killing. What seemed like a simple answer was about to get a lot more complicated.

The thing about criminals is that they lie all the time. The guessing game begins by figuring out who’s lying about what, and why. To figure out who killed George Hamilton, we are forced to play the game.

In 2003, Flemmi unburdened himself to the DEA. “Flemmi stated that George Hamilton was murdered as a favor by Bill Stuart for his [Stuart’s] employer, Ray Tighe, the owner of Allied Liquors,” his DEA criminal debriefing states. There are at least three problems with that sentence. Tighe is a misspelling—according to theories shared by many familiar with the documents, they were likely referring to renowned businessman and philanthropist A. Raymond Tye. Problem number two: There is no evidence that Raymond Tye was the owner of Allied Liquors. His company was called United Liquors. And I’ve been able to find no evidence that Stuart was ever employed by Tye.

Was it possible that Tye was somehow involved in Hamilton’s murder? Upon his death in 2010 at the age of 87, Tye was lauded as a hero: He’d made a fortune in the liquor business, then spent the latter part of his life quietly rescuing strangers, stateside and abroad, who were in desperate need of expensive medical care. He was a trustee of the Boston Public Library, a lifelong member of the NAACP, and a major donor to the Boston Anti-Defamation League. Certainly, Tye was incredibly well connected politically: He was tapped by Senator Ted Kennedy to provide medical care to an Iraq citizen seriously injured in the war, and Senator John Kerry called him “a guardian angel.”

I could find just two whiffs of scandal in Tye’s career, neither of which reflected poorly on him: In the late 1970s, a private loan he’d made to Ed Brooke—the Republican senator from Massachusetts and the first popularly elected Black senator since Reconstruction—ended up playing a role in Brooke’s political downfall, when Brooke lied about the loan under oath during a messy divorce proceeding. In 1988, several police officers were indicted for shaking down businesses for bribes; one of them, who claimed to be a close friend of Tye’s, was shown to have taken $15,000 from Tye for details that were never performed. The only conceivable connection I could find between Groper and Tye: At one point, apparently sometime prior to 2002, Groper’s company Branded Liquors was acquired by Tye’s United Liquors.

The question is: Did Bill Stuart intentionally mislead Stephen Flemmi about why he’d killed Hamilton? Or, in 2003, did Flemmi just misremember the wrong rich-guy liquor distributor?

When I came across Flemmi’s 2003 DEA debriefing, I hadn’t yet stumbled upon his earlier FBI memo from 1983. (Neither had the Norfolk DA’s office, for reasons that will become clear.) But the final sentence in the DEA item—in which Flemmi says he told his FBI handler about Stuart’s confession—made me wonder if someone at the FBI had a record of it. By then, most of Flemmi’s FBI file had been made public through the various trials of his boss, Whitey Bulger. Digging through court files, I found it: An FBI 302 report—the form that the government uses to memorialize an interview—dated January 17, 1983, in which Flemmi, then very much still in his criminal prime, told his handler, Agent John Connolly, that Norfolk DA Delahunt “wanted to indict [Stuart] for the murder of George Hamilton and would have done so had it not been for the intercession of [Massachusetts Attorney General] Frank Bellotti.” (Despite Boston’s attempts to contact Bellotti, he could not be reached for comment.)

In 1983, Flemmi’s statement indicated that Stuart offered him nothing more on the Hamilton killing but dished plenty of dirt on both Bellotti and Delahunt. That was no coincidence. Because at that exact moment, the FBI and the Norfolk County District Attorney’s office were in the middle of a vicious blood feud, the likes of which haven’t been seen since. The broad details were outlined in Dick Lehr and Gerard O’Neill’s classic book Black Mass: In the early 1980s, the FBI was desperate to keep Bulger’s status as a top-echelon informant secret, but rival law enforcement agencies, including the Massachusetts State Police, had begun to accuse the FBI of protecting Bulger.

In a series of preemptive strikes, Bulger’s FBI handlers—mainly Connolly—began to create a paper trail to discredit the agency’s detractors. At the top of their list: Delahunt and his chief investigator, State Police Major John Regan. The war took on many fronts. Most notably, in a case of whataboutism on a grand scale, the FBI pushed hard to get local and federal authorities to go after one of Delahunt’s confidential informants, the infamous art thief and bank robber Myles Connor. Not only was Connor charged (and acquitted) in a pair of murders, but the U.S. Attorney’s office opened a federal probe into Delahunt’s office itself.

During this period, Black Mass described a series of events that seemed to suggest, in January 1983, that Connolly preemptively sent Flemmi on a mission to dig up dirt on Delahunt that the FBI could use against him, including visiting one of his alleged paramours. What struck me about the Hamilton 302 was that it was recorded within two weeks of the fact-finding mission. It’s also worth noting that in January 1983, Flemmi was not technically an FBI informant: As a defensive move, the bureau had closed Flemmi out “administratively” because he was a suspect in an ongoing murder investigation. In point of fact, the bureau never told Flemmi he’d been closed, and Connolly continued to file 302s as usual.

It’s important to understand that FBI 302s, while they hold the power of law, are widely regarded as deeply suspect: One senior U.S. justice official described them to me as an exercise in light-fiction writing. In the case of an FBI 302 authored by Connolly, that was often doubly true. Throughout his protection of Bulger and Flemmi as FBI informants, Connolly regularly included lies, misinformation, and exaggeration in his reports as a means to throw off rival agencies or sometimes even rival agents. Then calculate the whisper-down-the-lane factor of Stuart’s story being funneled through Flemmi. And yet multiple law enforcement officers who’ve had dealings with Flemmi told me they believed his information about Stuart being Hamilton’s murderer was credible. There were times, they noted, when Flemmi had a reason to bullshit. This didn’t seem to be one of them. And he’d been consistent in that detail across 20 years.

Eventually, the U.S. Attorney’s office and the Massachusetts AG convened an intra-departmental summit conference to clear the air between the various factions, and the federal probe into Delahunt’s office ended without indictments. But the sniping and animosity continued. That’s almost certainly why Stuart’s confession via Flemmi to the Hamilton murder never made it from the FBI to the Norfolk DA. But it fails to explain how Stuart managed to stay free for the rest of his life—or how the official narrative shifted such that convicted murderer Billy Kelley, and not acquitted accessory to murder William Stuart, became the prime suspect.

Even if we believe Flemmi about who committed the Hamilton murder, how do we parse his allegations about Delahunt and Bellotti? The 302 quotes Flemmi saying Stuart got away with Hamilton’s murder because Stuart—who claimed to be an old friend of Bellotti—had so much dirt on Bellotti that the attorney general had taken it upon himself to dissuade his friend and mentee William Delahunt not to prosecute the case. Was this just a loudmouth, corrupt cop trying to show off for his former informant? Perhaps Stuart felt safe trading secrets with Flemmi because, as the person who’d introduced Flemmi to the FBI, he was one of the very few people in possession of the Boston FBI office’s most closely held secret. Maybe Stuart felt he was untouchable. Maybe he was right.

Last January, a former State Police captain named Joe “Buddy” Saccardo published a book called Capable. More than a decade ago, he had seen Flemmi’s unredacted DEA confession and wondered what became of the Hamilton investigation. In the book, Saccardo recounted that he tracked down a retired State Police detective lieutenant named Joe McDonnell, who’d been Delahunt’s original investigator on the murder case. Stuart was then a key suspect, and during an interview at a Dedham restaurant, Stuart admitted to McDonnell that he had once owned a .38 special—which police suspected was the murder weapon—and McDonnell believed that Stuart had once fired the gun in the back area of Hamilton’s, Saccardo wrote. Conveniently, Stuart told McDonnell that he no longer had the weapon. What’s more, when Saccardo interviewed McDonnell in 2011, McDonnell “was still bitter as hell” at Delahunt for taking him off the case. Reading that passage, and in further talks with Saccardo—who also passed along invaluable documents on Stuart and Flemmi—it was hard not to begin connecting the dots.

Was it possible someone squashed the case against William Stuart? Maybe Stuart—with his history on both sides of the law—had just enough pull to knock the investigation off its course. Or maybe the real power had been the influence campaign the Globe wrote about after Groper and Levin were initially convicted—a campaign that seemed to have support in the state’s highest office.

Over a period of months, often with Saccardo’s help, I began looking into Kivlan’s suspect: Billy Kelley, the guy who’d ended up on death row for an unrelated 1966 murder. The more I learned, the less likely it seemed that Kelley was the triggerman in the Hamilton killing. For one thing, Kelley was never mentioned as a potential suspect until at least 1984. By then, Groper and Levin were on their way to acquittal, and Delahunt and Kivlan may have begun to realize just how powerful their opponents were. Perhaps at some point they decided—or were convinced—to cut their losses and, at least privately, give Hamilton’s family some sense of closure by suggesting that the man who killed George was already serving the ultimate punishment.

When I approached the Norfolk County DA’s office in late 2022, they were helpful to a point, short of reopening a 50-year-old investigation in which almost all the players are dead. Ironically, but for Kelley clinging to life on death row in Florida, the DA could declare the case closed and release its records. What I gleaned from conversations with the people who’d investigated the case over the years was that Stuart had been a prominent suspect until at least after the first fraud trial in 1979. Nobody seemed to know where the Kelley theory had come from. The best chance to find out would have been to ask Kivlan. Shortly after I approached the Norfolk County DA’s office about the case, investigators arranged a meeting with Kivlan to ask him about the case. And then, unfortunately, Kivlan passed away.

Eventually, digging through thousands of pages of Kelley’s court transcripts—he hadn’t been indicted for the 1966 murder until 1983, and thereafter, he’d gone through two full trials and half a dozen appeals—I came across a hint of who’d first put Kelley’s name into the Hamilton case. It was Kelley’s own lawyer, and he brought it up only glancingly in an attempt to discredit Kelley’s main accuser in the Florida case: John Sweet, the same person Kivlan and his colleagues had visited to gather intel on the Hamilton case. Could Sweet have convinced Kivlan that Kelley was Hamilton’s killer? According to Kivlan’s colleague Matt Connolly, who was present for that conversation, Kivlan quickly pegged Sweet as a con man. But perhaps—just maybe—that thin thread was enough to ease Stuart out of the line of fire.

Kelley turned 80 in December 2022 and, at presstime, remains the second-oldest person on Florida’s death row. He has long exhausted all of his appeals. Last June, he sent me a short, signed statement saying, “I did not plan, participate in, or have any involvement in the murder of George Hamilton in Canton, Massachusetts, in April of 1976.” He also said he believed Sweet was the source of those allegations.

There was one final detail I found in Kelley’s court documents. It came from an appeal that landed him closer to freedom than he would ever reach again—so close that at one point, he was packing his clothes, and his brother was preparing to pick him up. Against all precedent, a judge had ordered a new evidentiary hearing and heard testimony that suggested—decades after the murder—that Kelley had been the victim of a case of mistaken identity. A 20-year-old identification had come under scrutiny, and there was an argument about whether Kelley actually fit the description. The person who had committed the crime, Kelley’s defense claimed, was a man named Steven “The Greek” Busias. The star witness was the Greek’s own son, who testified that his father had traveled to Boston around the time of the murder, returning flush with cash before opening a nightclub. Hobart Willis, a tired old thug with a bad heart, testified via video deposition that the Greek had confessed to him that he carried out the Florida killing.

And then there were a pair of depositions from 1987 and 1988 from none other than retired Boston Police Officer William Stuart, on behalf of Kelley’s defense. In all of his years surveilling organized crime figures, Stuart wrote, “I came to the conclusion that Billy Kelley was not an organized crime figure, nor was he involved with organized crime.” Steven Busias, on the other hand? Stuart wrote that he knew the Greek well: Busias had been a informant of Stuart’s and was a known associate of two men who’d planned and executed the Florida murder.

I knew, reading Stuart’s reports, that he’d been lying through his teeth: Boston Organized Crime Squad officers tailed Kelley and his wife relentlessly over the years, and he’d been tied by numerous witnesses to the same associates Stuart now pinned on the Greek. Here was Stuart, giving up his former informant in an attempt to get Kelley out of jail—why?

The last man who might possibly answer these questions—the lingering haze over why Stuart was never prosecuted, why Kelley was subbed in as a suspect, and why the second fraud trial felt to Hamilton’s family like a foregone surrender—is William Delahunt. I tried to reach the retired congressman for more than six months before finally receiving word through a spokesman that he wouldn’t comment for this story.

For Hamilton’s family, the ghosts are never entirely gone. It’s no longer about finding justice for George: It’s too late for that. Stuart died of cancer in 2000. Levin died in 2002. Groper died in September 2022. George’s sister, Phyllis Lang, watched their parents struggle with the weight of an unbearable grief—toward the end of his life, George’s father told his family he didn’t fear death, because it meant he would finally be reunited with his son. Phyllis’s son, Jonathan Lang, resembles her brother so much that she sometimes does a double-take when she sees him.

In 1987, when he was 17, Jonathan Lang heard a knock at the front door, and when no one was there, he looked to the back patio and saw the face of evil: 17-year-old Daniel LaPlante, who was then on every television screen in Boston as a fugitive in the savage rape and triple homicide of a mother and her two young children. LaPlante, shouting, held a gun and begged to be let in the house. Lang refused before calling the police; LaPlante was captured a few hours later. But for Lang’s family, the echo was unmistakable: The unthinkable had almost happened again. Now Jonathan, who has worked in theater for decades in Florida and Boston, has become the family historian: He’s been working on a project based on his uncle’s story and also his own. As his sister Pamela Johnson—Hamilton’s niece—put it, “When you think about [George’s] story, why would you tell it now? There’s nobody around to be punished for it. I think it’s different now—when crimes happen, there’s so much detail. But back then, in the ’70s, there wasn’t. And I don’t think his story has been told as much as it should’ve been.”

First published in the print edition of the February 2024 issue with the headline, “How to Get Away With Murder.”