Why Harvard University Is Failing at Everything

A crushing cancel culture, accusations of plagiarism, protests on campus, lawsuits, Congressional investigations, and big-dollar donors running for the door. Inside the campus turmoil, where the emperor by the Charles has no clothes.

Illustration by Dale Stephanos

It was an early moment of truth in the fledgling Harvard presidency of Claudine Gay. Called to testify in front of Congress about rising incidences of antisemitism on campus, Gay made her way to the Capitol on December 5 sporting her signature black-rimmed glasses, a classic gray suit, and a slight air of annoyance at having to explain herself to a committee stacked with skeptical Republicans.

The past few weeks had already been challenging for Gay, who was dealing with a torrent of unrest at Harvard following Hamas’s shocking October 7 assault on Israel. Almost immediately after the deadliest day for Jews since the Holocaust, more than 30 student groups issued a pro-Palestinian statement squarely blaming Israel for “all unfolding violence”; this was followed by massive protests on campus, during which participants chanted antisemitic slogans. Some students reported being harassed, assaulted, and intimidated while on school property. In the midst of it all, Gay herself came under fire for not publicly addressing the attack quickly enough and not condemning Hamas strongly enough when she finally did.

Seated in the hot seat with the microphone inches from her face, Gay had already watched her fellow panelists, MIT President Sally Kornbluth and the University of Pennsylvania’s Liz Magill, drop jaws with their claim that calling for the genocide of Jews on campuses with significant Jewish populations might not violate their rules against bullying and harassment. As Magill said, “It is a context-dependent decision.”

Then it was Gay’s turn. “At Harvard, does calling for the genocide of Jews violate Harvard’s rules of bullying and harassment, yes or no?” asked Republican U.S. Representative from New York Elise Stefanik, a Harvard graduate herself.

“It can be, depending on the context,” Gay replied unemotionally.

Former president Claudine Gay testifies before Congress. / Photo by Mark Schiefelbein/AP Photo

The response, among other statements from Gay during her testimony, immediately set off an international firestorm. “I’m no fan of @RepStefanik but I’m with her here,” tweeted arch-liberal Harvard Law School professor emeritus Laurence Tribe of Gay’s “hesitant, formulaic and bizarrely evasive answers.” Even White House officials weighed in: “It’s unbelievable that this needs to be said: calls for genocide are monstrous and antithetical to everything we represent as a country,” said deputy press secretary Andrew Bates in a statement. Gay herself apologized a few days after her testimony, telling the Harvard Crimson: “I got caught up in what had become, at that point, an extended, combative exchange about policies and procedures. What I should have had the presence of mind to do in that moment was return to my guiding truth, which is that calls for violence against our Jewish community—threats to our Jewish students—have no place at Harvard and will never go unchallenged.”

Truth. The Congressional debacle was a rare and revealing glimpse into how far Harvard has strayed from the single Latin word—veritas—emblazoned on its seal. But in reality, it shouldn’t have surprised anyone that Harvard would handle this globally broadcast moment with such a tone-deaf, veritas-free spin. In fact, for a school that has always managed to sidestep external scrutiny, Harvard now finds itself under an electron microscope that is exposing just how deep the flaws are of this formerly impervious university.

Over the past few years alone, Harvard’s coveted image as the pinnacle of academic excellence has been taking a beating. Gradeflation is out of control: By 2021, 79 percent of students received A-range grades—compared to 60 percent a decade earlier. Two school leaders, Harvard diversity and inclusion chief Sherri Charleston and Gay herself, have recently been accused of being plagiarists. The Harvard Kennedy School, created to incubate public-sector leaders, has mostly become a finishing school for private sector executives. While construction crews toil away on Harvard’s long-delayed life-sciences mini city in Allston, it’s hard not to wonder what Harvard brass was thinking—or not—when it watched MIT for four decades build the biotech epicenter of the world in Kendall Square. Meanwhile, top life-sciences academics from Harvard are bolting for up-and-running competitors. As for the vaunted Harvard Business School (HBS), its rankings dropped sharply in the most recent Bloomberg Businessweek MBA standings to its lowest spot in nine years. Perhaps most frightening of all to the faculty and students for whom the Harvard brand is a passport to big jobs and contracts with high salaries, the business school has fallen behind its competitors at Yale, Dartmouth, and Cornell in job offers for graduates.

Meanwhile, the reality of the campus environment is far removed from the glossy brochure images of undergrads happily strolling beneath ivy-covered walls. Harvard students who aren’t terrified of getting confronted or canceled by the ‘woke mob’ are often left wondering when their campus became the place where fun goes to die. At the same time, prominent alumni already alienated by Harvard’s increasingly strident political climate were further repulsed by the post–October 7 hurricane of inept management and arrogant disregard for their input. And in what maybe the most telling rebuke of a place where, truth be told, money and status-seeking long supplanted veritas, big-money donors are bailing—a painful injury added to the insult of embarrassingly poor endowment investment performance.

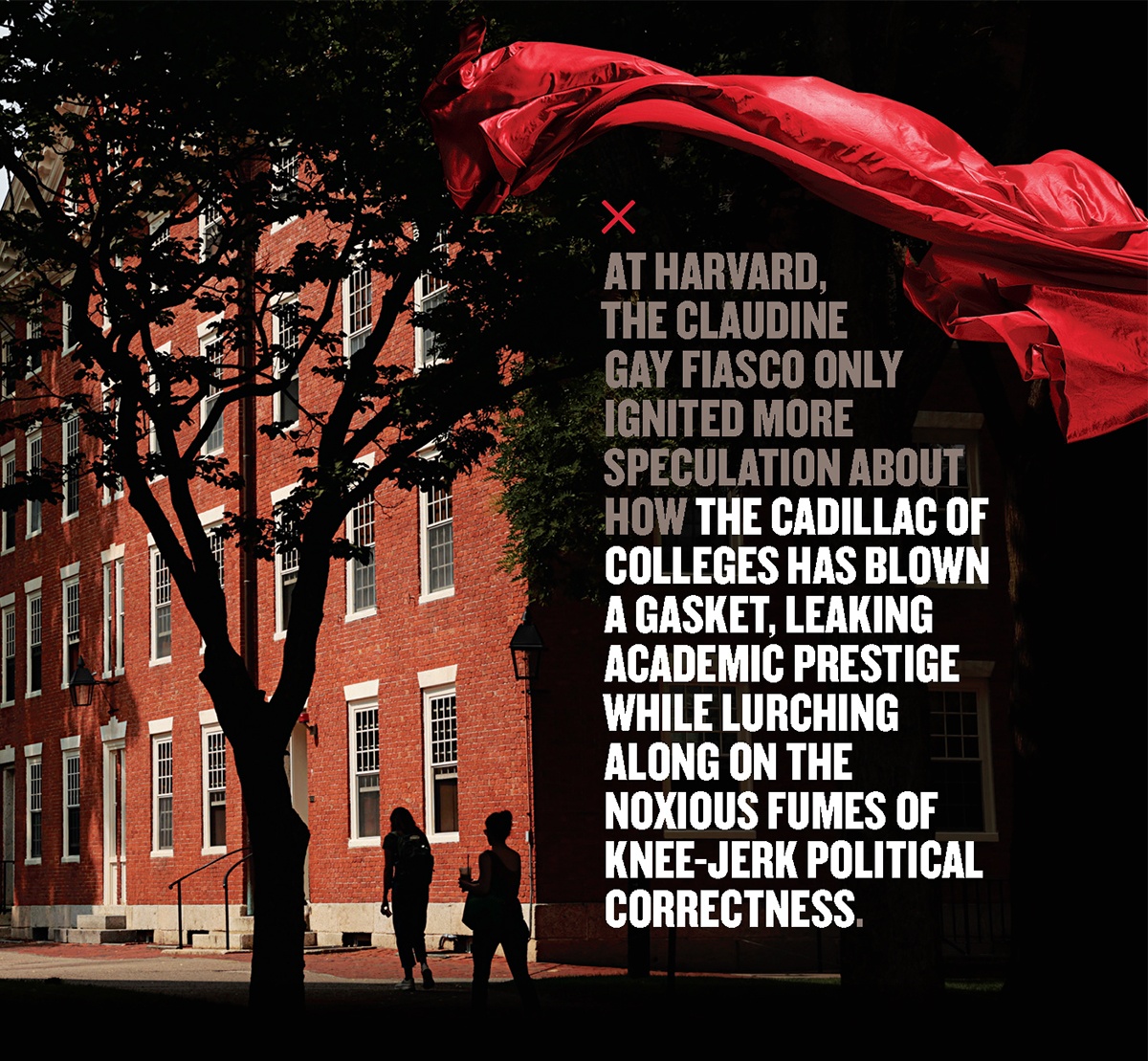

Photo by Boston Globe/Getty Images

Regardless of what level of education is offered in the classrooms, it’s enough to make you wonder—could one of the world’s best-known and admired brands be past its prime? With the possible exceptions of the Bible and the Beatles, no great brand lasts forever. Just ask the folks behind the Duesenberg, the automotive star of the 1920s done in a decade later by mismanagement and the Depression; Pan Am, which led the boom in air travel before federal industry deregulation and the terrorist bombing over Lockerbie took their toll; and Cadillac, the ne plus ultra of luxury cars brought low by the end of cheap gas.

It seems even the most successful institutions can be humbled by their own arrogance and miscalculation of changing economic and political realities. In Harvard’s case, the Gay fiasco only ignited more speculation about how the Cadillac of colleges has blown a gasket, leaking academic prestige while lurching along on the noxious fumes of knee-jerk political correctness. “When you’re more concerned with making everybody feel good rather than having serious debates about the truths of our world, you’re going to fall into this malaise, where faculty are scared of students, administrators are afraid of faculty, and everybody consults a lawyer before doing anything,” says U.S. Representative Seth Moulton, Harvard College Class of ’01 and the recipient of master’s degrees from the Kennedy School and HBS. “The brand has been tarnished, but in part because of Harvard’s own doing.”

All of this doesn’t just put into question the value of a Harvard education; it also puts into question the entire value proposition of college itself. If students can’t freely learn and discuss ideas, what is the point of dropping more than $200,000 for a degree? Harvard’s failures have done more than a disservice to the university—they’ve done a disservice to higher education as a whole.

It’s all quite the indictment of an academic institution that has ruled the roost for centuries while proudly sporting the regalia of its illustrious history. These days, though, it seems the emperor by the Charles has no clothes.

The first college of the colonies, Harvard was created in 1636 with a £400 government grant—more than $110,000 in 2024 dollars, significantly less than the salary of a Harvard professor today. Its first commencement consisted of nine graduates. One hundred and thirty-four years later, eight of its alumni were among the signers of the Declaration of Independence.

Throughout the 1800s and into the 20th century, Harvard’s stature—and, by extension, its complexity—mushroomed. As early as 1869, newly installed school President Charles William Eliot could boast that “this University recognizes no real antagonism between literature and science, and consents to no such narrow alternatives as mathematics or classics, science or metaphysics. We would have them all, and at their best.”

Yet by the 1930s, key Harvard caretakers began expressing concern over whether the school could continue to live up to its reputation. As the tercentenary celebration in 1936 neared, Harvard’s celebrated reformist President James Bryant Conant wondered in a report to the university’s board whether places like Harvard that had grown “startlingly large and complex” could “escape the curse which has so often plagued large human enterprises well established by a significant history—the curse of complacent mediocrity? What will be written and said about the role of the university…when the four hundredth celebration draws near in the winter of 2036?” A more prescient statement could not have been uttered.

Though Harvard’s roof is far from caving in—when you’ve got $50.7 billion, you’ve got $50.7 billion—waiting until 2036 for a thorough inspection of one of the country’s wealthiest and most prestigious institutions probably isn’t a good idea given the cracks now showing in Harvard’s academic edifice. It’s been 18 years, for instance, since Harvard began the process of transforming university-owned land in Allston into a massive science-oriented campus that, according to the house organ Harvard Gazette, would help it “maintain academic leadership into the next century.” Ever since then-President Drew Faust temporarily put the project on hold in 2009 due to the recession, Harvard has been left playing catch-up with “lesser” rivals such as MIT, which played a huge role in Kendall Square’s 21st-century biotech boom. That neighborhood now has the greatest concentration of biotechnology companies in the world, which regularly work with and draw from MIT’s vast talent pool.

One consequence of Harvard’s lack of life-sciences progress has been brain drain. In one instance, renowned scientist and Broad Institute cofounder Stuart Schreiber recently bolted from the Harvard faculty to start a powerhouse Kendall Square drug research and development institute, Arena BioWorks, which has been aggressively poaching employees from university labs. It would take Harvard years or even decades to match its facilities, and in any case, the days of the university’s preeminence in funding for such ventures seems long gone—Arena BioWorks’ major investors include Celtics co-owner Steve Pagliuca, a Duke grad, and billionaire investor Michael Dell, who dropped out of the University of Texas.

Other areas of the university are similarly lacking. Harvard may still have the best-known name in American politics adorning its school of government, but it no longer sports the best reputation for nurturing public-sector leaders. While the Kennedy School has produced more heads of state than its competitors, these days, its graduates are just as likely to be found working at consulting firms or hedge funds as government agencies—as evidenced by the whopping 44 percent of the Class of ’22 who went to work in the private sector.

It’s a trend that’s been building for years. A 2017 article in this magazine referenced a Kennedy School instructor’s research from the early 2000s that found striking levels of “skepticism and disdain” toward government among students and “a decline in stated interest in government careers.” Students are not encouraged to think otherwise by official policy; the word “government” was removed from the school’s promotional materials in the late 2000s and is absent from its online mission statement.

Most recently, the Kennedy School stepped in it over one of the most pressing political issues of our times when it dismissed online disinformation expert Joan Donovan from the faculty as a result, she claims, of her harsh criticisms of Facebook and its parent company, Meta, both of which are the brainchild of mega-donor Mark Zuckerberg. Was the Chan Zuckerberg Initiative’s $500 million gift enough to buy Donovan’s silencing? Harvard has adamantly denied it and claims the research into Facebook’s culpability for misinformation continues. But Donovan’s accusations are still picking up steam. “If you think the plagiarism scandal or the failure to address antisemitism and Islamophobia are the biggest problems facing Harvard today, read my account of how donors from Facebook influenced [Kennedy School] Dean [Douglas] Elmendorf to shut down my research lab and prevent me from digging into Meta,” tweeted Donovan, who is now on the faculty at Boston University.

Donovan’s low grade for Harvard is an anomaly on a campus where a jaw-dropping 79 percent of undergraduates got As during the 2020 to 2021 academic year. That’s a 19 percent increase in As over just the past decade. Grade inflation has been a long-term trend in American education, but reports show the Ivy Leagues lead the parade, with Harvard’s grade point average on par with Yale’s. Are the students getting smarter? Perhaps not. After a meeting last fall of the Faculty of Arts and Sciences, dean of undergraduate education Amanda Claybaugh told the Crimson that while many grades were well deserved, external “market forces” have been influencing grading, as faculty are reliant on positive course evaluations from their students for professional advancement.

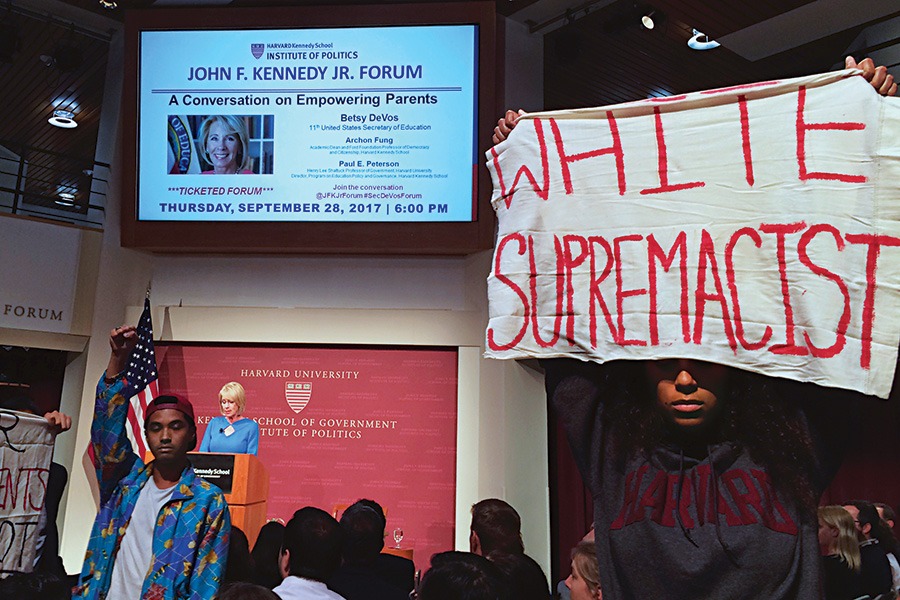

Students also railed against former Education Secretary Betsy DeVos when she came to speak at the Kennedy School in 2017. / Photo by Maria Danilova/AP Photo

Beyond the questionable grading of students, the campus has become a breeding ground for political intolerance, particularly when it comes to more-conservative voices. Student comments gathered by the Foundation for Individual Rights and Expression (FIRE) for its annual rankings of free-speech climates on campuses range from scathing to sad. “I felt very alone,” wrote one senior who self-described as a moderate Republican. “It is an incredibly difficult and isolating political landscape to navigate.” One recent graduate noted, “I’ve had many moments where I didn’t want to disagree with the most ‘woke’ take during class for fear of backlash.” It makes sense on a campus where, as FIRE noted, 41 percent of Harvard students surveyed think it’s at least sometimes acceptable to shout down an individual to prevent them from speaking on campus. No wonder the school was given an “abysmal” rating and ranked dead last in the national pack.

This culture of intolerance has extended to the Israel/Hamas war, as evidenced by a pair of recent legal complaints filed against the university. Appalled by last fall’s aggressive, unrestrained displays of anti-Israel animus—including an instance in which two “visibly Jewish” law school students said they were regularly stopped and targeted in the student lounge based on their clothing—in January, a group of Jewish students sued Harvard, alleging that the university is in violation of Title VI of the 1964 Civil Rights Act. In the federal lawsuit, the students noted that the university has “at least five applicable sets of policies ostensibly to protect students from discrimination, harassment, and intimidation” that it failed to enforce last fall, despite threatening penalties in training classes for engaging in everything from “size-ism” to “fatphobia” to “transphobia” on campus.

That same month, the Muslim Legal Fund of America filed a civil rights complaint with the Department of Education on behalf of Palestinian students at Harvard, alleging the administration failed to protect them from discrimination. The allegations include instances in which they were stalked, threatened, and even assaulted on campus for wearing keffiyehs, traditional Palestinian scarves.

Beyond conflicts with their peers, students have had to endure the cold shoulder from Harvard—in some cases, quite literally. When the kids returned from their winter break earlier this year, the heat was out at Leverett House, sending some students fleeing for hotel rooms while others slept in jackets, hats, and gloves, according to the Crimson. Other dorms have also struggled with heat and hot water shortfalls. The issues aren’t a one-off. A 2019 Crimson article reported “repeated issues with [Harvard University Housing’s] infrastructure, including flooding and broken elevators.”

Students and their parents are noticing. When one mother moved her son into Cabot House recently, “it looked like something out of the ’50s,” she said. “There was peeling lead paint on the windowsills. What are they doing with their $50 billion endowment?” At Peabody Terrace, graduate students dealt with those and other problems in 2019, including destructive renovations and “days without water,” according to the Crimson. Kennedy School student Emma Margolin’s computer printer and charger were damaged by flooding and other issues, and she was displaced from her room for six days. When she sought rent compensation, Harvard officials refused, she said, choosing instead to give her some gift cards from Whole Foods.

If you had major maintenance issues in your home, you probably wouldn’t hesitate to throw money at the problem. But at Harvard, problems with campus upkeep persist despite the university’s massive wealth, which the administration could ostensibly use to improve the facilities if that were a priority.

Not only are some campus buildings in need of a little TLC, but Harvard Square itself is a symphony of for-lease signs that blight one of the most valuable pieces of land in America. The square is an outgrowth of Harvard’s campus, yet the university has shown little leadership in improving its appearance, choosing instead to turn its back on their own front yard. Conversely, Boston University saw a decaying Kenmore Square as a blight on the school and invested in the strip, including partnering on the construction of major hotel, restaurant, and office developments over the past four decades. In doing so, they repositioned the area into an asset for the campus.

Harvard Business School dropped sharply in Bloomberg Businessweek’s latest rankings, to its lowest point in nine years. / Photo by Dariusz Jemielniak (“Pundit”)/Creative Commons

Then again, perhaps it’s wise for Harvard to be penny-pinching—especially in light of the recent exodus of big-dollar donors. Take, for instance, Tim Day, a Marine Corps veteran and 1964 graduate of Harvard Business School who went on to make a fortune in the processed-meat industry. He’s given millions over the years to fund HBS fellowships for former and current Marines, as well as $5 million for a gleaming new fitness center that bears his name. These days, though, he’s openly questioning whether Harvard is fit to pocket any more of his charity. “I am very much against the whole diversity, equity, and inclusion aspects that have been built into the culture at Harvard,” he tells me. “I thought it should be purely a merit-based system.” Day was also “shocked” by what he saw as a “lack of concrete action to protect the Jewish students” on campus after October 7. He’s holding back further donations, he says, until he sees concrete evidence that Harvard is serious about making changes.

Billionaire businesspeople who’ve given hundreds of millions to Harvard, either individually or through their foundations—such as Leslie Wexner of Bath & Body Works fame, Israeli philanthropist Idan Ofer, and hedge-fund guru Bill Ackman—have also bailed in the wake of the administration’s botched response to October 7, along with countless smaller donors. Most recently, Citadel hedge-fund founder Ken Griffin, who has donated $500 million to the university over the years, announced he’d be shutting his checkbook until the school stops producing “whiny snowflakes” who are “caught up in the rhetoric of oppressor and oppressee.”

Griffin sees the broader failure of Harvard and his withdrawal as a donor as akin to a nuclear bomb going off in the school’s endowment office. But there are other problems there, too. Despite virtually unlimited resources, the university’s endowment team made a measly 2.9 percent return on its investments in fiscal year 2023, managing to underperform a Charles Schwab money market account, whose returns hover around 5 percent. Add all of that to expenses that are growing faster than revenues, and it’s clear that, as Harvard chief financial officer Ritu Kalra told the Crimson, the university has “a lot of repair work to do.”

A woman prayed for the Israeli hostages adjacent to another pro-Palestine rally at Harvard. / Photo by Boston Globe via Getty Images

So far, Harvard hasn’t done a great job of allaying donors’ concerns. Rabbi David Wolpe, appointed by Gay last fall to an advisory committee designed to curb campus antisemitism, says he resigned from the group in part because “changes weren’t happening on campus. Things were at least as bad or getting worse.” Advisory committee suggestions for easing the “culture of intimidation” of Jews on campus by “enforcing policies, not allowing protest to interrupt classes, [and] making sure professors didn’t turn seminars into political events” were being paid lip service but not being implemented, Wolpe explains. Instead, he believes Gay’s administration was enabling these behaviors “if enabling is defined as being able to put the brakes on something more than you have.”

Gay resigned in early January following her disastrous Congressional testimony and accusations of plagiarism, but the era following her presidency so far hasn’t been any more promising in that regard. Case in point: Interim President Alan Garber recently received some criticism for appointing a harsh critic of Israel, Professor Derek Penslar, to cochair a new and supposedly improved antisemitism task force. “He is unsuited,” tweeted former President Lawrence Summers. “Could one imagine Harvard appointing as head of [an] antiracism task force someone who had minimized the racism problem or who had argued against federal antiracism efforts?”

Jewish voices haven’t been the only ones calling out the university’s unwillingness to crack down on campus antisemitism. “Any form of protest that disrupts the conduct of a class violates basic prohibitions against interference with the normal duties and activities of the university,” wrote one of Harvard’s leading Black scholars, political philosophy and ethics professor Danielle Allen, in a Washington Post op-ed.

Lost prestige, financial pressure, anxious (and cold) students, dismayed faculty, furious alumni, and donors voting with their wallets—that’s some bad karma, all right. Still, as Gay was hustled to the curb the day after New Year’s like a once-festive family Christmas tree turned unwanted fire hazard, there was no immediate sign that anyone in power at Harvard truly grasped the depth and severity of their problems, let alone had a clue what to do about it. In a New York Times op-ed piece published the day after her resignation, Gay offered a spin widely echoed by defenders of Harvard’s status quo—that her exit was the work of outside “demagogues” out to “undermine the ideals animating Harvard since its founding: excellence, openness, independence, truth.” Universities like Harvard, she wrote, “must remain independent venues where courage and reason unite to advance truth, no matter what forces set against them.”

For all the handwringing over the hard time being given to Harvard by outsiders—presumably including the U.S. Supreme Court, which threw out the university’s race-based admissions programs, and the U.S. House Ways and Means Committee, which is investigating whether the mishandling of antisemitism at Harvard and other campuses might compromise their tax exemptions—the university’s embrace of outside forces is actually a fast-growing feature of campus life. According to the Network Contagion Research Institute, Harvard pocketed $894 million from foreign governments—the large portion of which were authoritarian regimes—during a five-year stretch of the 2010s. The institute’s study of the fallout from $13 billion worth of such funding to 203 American colleges and universities concluded that it resulted in “heightened levels of intolerance toward Jews, open inquiry and free expression.” When asked about foreign donors at the Congressional hearing, Gay gave this context: “We will not accept gifts that do not align with our mission.”

Protesters decrying the Supreme Court’s ruling against affirmative action policies at Harvard last year. / Xinhua News Agency/Getty Images

For all of its wealth and sprawl, what has always distinguished Harvard from lesser institutions is the esteem in which it is held by the marketplace—by prospective students, alumni, and outsiders. So when a self-proclaimed bastion of tolerance and courageous upholder of veritas is shown to harbor intolerance and debase standards while offering unpersuasive denials of it all, it’s time to call in the brand doctors.

One of the first things the university should work on, believes Edward Boches, a former chief creative officer for the MullenLowe ad agency who’s done work for General Motors, Google, and other blue-chip companies, is transparency. With the advent of social media and the Web, “brands of every kind lost the ability to control their messaging,” he explains. “You saw the most progressive and open-minded brands actually embrace that—how to be more transparent and interactive. Harvard is one of those who’ve stayed completely closed.”

Gay touched on the idea of openness in her inaugural address back in September, citing a litany of ways in which Harvard should open up. “Why not reach as many people as possible through our educational programs?” she asked. “Why not open our treasure troves of books, objects, and artifacts to the world?”

Still, when it comes to criticism of the university, Harvard tends to snap shut faster than a Venus flytrap. Journalists are likely to have better luck getting quotes from the Vatican than from the Harvard administration (who did not respond to a request for comment on this article). As Kennedy School professor Khalil Gibran Muhammad put it during a recent GBH radio interview: “The communication strategy of my employer is not to speak publicly on just about anything.”

The problem of communication, or the lack thereof, runs deep in Harvard’s culture. In just one example, Vanessa Beary, a graduate of and donor to Harvard’s Graduate School of Education, resigned in disgust from the board of the Harvard Alumni Association when she saw that the HAA’s executive committee—without consulting other members of the association, she says—had issued a statement supporting Gay after her Congressional testimony. For Beary, it was the climax of more than a decade of frustration with “the absolute lack of political diversity” she experienced at Harvard, including “blanket statements being made by students that are egregious and going unchallenged by the professor.” As she says, “It’s about Claudine, but it’s also about Harvard, going back three presidencies. It’s entrenched.”

As with any valuable brand, blunders have consequences. In a postmortem for Fortune magazine, Yale management guru Jeffrey Sonnenfeld wrote that “by allowing the erosion of the school’s public reputation for integrity and truth and a breakdown of trust internally, the board was negligent in attending to the priorities of key stakeholders: students, faculty, staff, and alumni. The board’s negligence has damaged the attractiveness of Harvard to the outside world.”

What now? Boches reaches the conclusion that Harvard needs transfusions of humility and openness, stat—a finding echoed by University of Maine communications expert Michael Socolow. Socolow cites the teachings of the late Edward Bernays, a longtime Cambridge resident who was known as “the father of public relations.” In his 1928 book Propaganda, Bernays suggested two possibilities when a university is hit with criticism: Either “the public is getting an oblique impression of the university, in which case the impression should be modified; or it may be that the public is getting a correct impression, in which case, very possibly, the work of the university itself should be modified.”

When it comes to Harvard, Boches says, that translates to making “enough change to the governing body so they can talk about it.” They should also “embrace and foster some different perspectives, then make sure the world knows about it.” Finally, “they need to do a better job of anticipating consequences of future criticism—they can’t just issue a press release or make a speech.” Professor Muhammad expressed a similar sentiment in his radio interview, saying, “Harvard’s strategy of rising above the fray and choosing silence over engagement has run out of road. It is no longer effective.”

Which brings us back to the word Harvard long ago embraced as the definition of its brand: veritas, the motto that, in the hands of this generation of university leaders, has become a sad, ironic antonym. “The meritocratic university nurtured the ideal of detached, objective scholars committed to the pursuit of truth,” wrote Brandeis University historian Morton Keller and longtime Harvard associate dean Phyllis Keller in their coauthored 2001 book Making Harvard Modern: The Rise of America’s University. “But in many areas of the academy, a new, postmodern skepticism with regard to objectivity and truth has come into its own. Closely related is political correctness, with its deadening effect on the free exchange of ideas…it is arguable that Harvard today is no more (and possibly less) open to diversity of thought than it was at the height of the Cold War during the 1950s.” (Full disclosure: The Kellers also happen to be this author’s late parents.)

Two decades later, Representative Moulton sees the same rot. He was appalled at Gay’s reluctance to immediately condemn Hamas following the October 7 attacks, a hesitancy he sees as reflective of an over-eagerness to accommodate opinions rather than shape them. “It’s not that hard to say that terrorism is bad—it doesn’t require a Ph.D. to say,” he says. “You used to go to Harvard to learn how to lead—now it seems you go to learn how to concede.”

Harvard is not the first great venture to overlook the cracks in its foundation. “Every institution, however successful, carries within it the seeds of future trouble,” wrote the Kellers in Making Harvard Modern. After the industrial revolution, the German universities of the 19th century became international role models, just as Harvard did in the 20th century. Then came the two world wars. Observed the Kellers: “That preeminence, to understate the matter, did not last.”

Can Harvard stop its slide by reforming its management style, practicing what it preaches about openness and truth, and, not least of all, making sure the heat works in the dorms? Looking back over the sweep of the university’s history, there have been numerous times when leaders stepped up to confront social and economic upheaval, rejuvenate the institution’s mission, and keep the place growing and relevant. They shaped the circumstances of their time for the better and left behind a university valued far beyond its immediate constituents.

So the answer is, yes, Harvard can most likely get its act together this time, too. But it all depends on the context.

First published in the print edition of the March 2024 issue with the headline, “The Crimson Has No Clothes.”