A Conservative Thought Experiment on a Liberal College Campus

Last fall semester, professor Eitan Hersh and a class of undergrads embarked on a mission to understand conservative thought. Here's what happened.

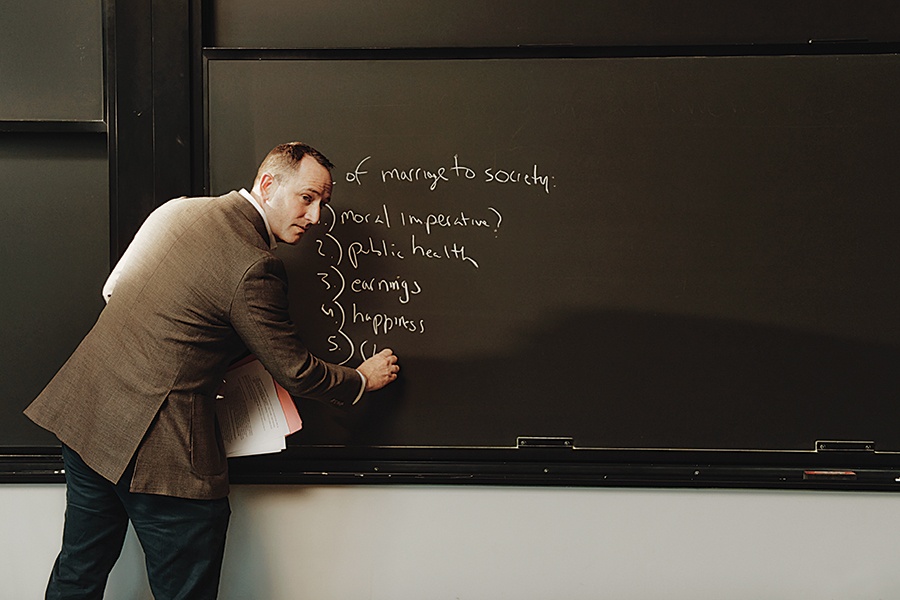

Hersh jots down a few notes on the blackboard for his American Conservatism course at Tufts University. / Photo by Tony Luong

On the first day of class in September, Tufts University undergrads scurry into Room 104, Barnum Hall, to grab a spot in one of the dozen rows of bright-red and yellow upholstered seats. They don’t know one another yet, so most of them have their heads down as they stare self-consciously at their phones. As the minutes tick by, the room fills up with young people in T-shirts, yoga pants, and crop tops (it’s 80 degrees outside, after all). Backpacks hit the floor as a water bottle rolls under a seat; someone fishes it out.

At 10:29 a.m., Professor Eitan Hersh bursts through the door, pulls out an Expo marker, and scrawls a few numbers onto the whiteboard:

30 percent of Americans call themselves liberal.

35 percent call themselves moderate.

36 percent call themselves conservative.

Those numbers are from a 2022 Cooperative Election Study, he says. The largest racial group of conservatives is white—no surprise. Native Americans and Hispanics come in a close second and third. The wealthier you are, Hersh says, looking out at the sea of young diploma-seekers seated before him, the more liberal you’re likely to be.

The students barely nod in assent. The fact that they’re sitting in a plush Tufts classroom on a beautiful fall day proves that many of them come from supportive homes, many with resources. The fact that they signed up for a class about American conservatism shows that they are, in many cases, grappling with that privilege.

Twitchy and youthful with a quick wit, Hersh is a 40-year-old Tufts graduate and political science professor renowned on campus for his tightly structured lecture classes, which draw impressive crowds. While co-teaching a seminar class with him a couple of years ago, I learned how he’d carved out a place for himself as a self-styled “right-leaning centrist” who is working to counteract what he sees as the overabundance of liberal thinking on campus.

Hersh is not quite a code-red alarmist, à la Bill Ackman—the Harvard-educated hedge-fund billionaire who told New York magazine that after his daughter came home from Harvard “an anti-capitalist…practically a Marxist,” he decided to wage war on higher ed, which he said had all but indoctrinated his daughter into a “cult.” Already vocal about his opposition to Harvard’s DEI initiatives, he became the poster boy of the conservative attack on higher ed when he spearheaded calls for a plagiarism investigation of the school’s then president, Claudine Gay, which resulted in her resignation in January.

Hersh hasn’t come to quite the same conclusion as Ackman, but he does know that there’s a paucity of conservative teaching on campus—liberal professors, after all, outnumber conservative professors 28 to 1 in New England, according to a 2016 study of data from the Higher Education Research Institute—and he believes it’s pedagogically important to offer diverse perspectives and voices. “Sometimes good ideas emerge from the right, and sometimes they emerge from the left,” Hersh tells me. “And you’ve got to burst the bubble that either democracy or the good life for American society is going to emerge exclusively from the left.”

Photo by Tony Luong

Hersh believes that the veritable absence of conservative teaching may be the result of a few different factors. It could be because of an intentional effort to shelter students from conservative ideas; it could also be because there is a lack of educators who are interested enough in the ideology to create a class and teach it. Indeed, when Hersh told his colleagues in the political science department last year that he wanted to design a class that exposed students to the modern American right, they told him to go for it. There was just one catch: Hersh would have to build the course from whole cloth, because nothing like it existed on college campuses anywhere in the United States. He did find a few course models that tackled the conservative movement through political history or looked at the foundations of political philosophy going way back to Italy’s Niccolò Machiavelli, but they were largely taught through a liberal lens. Instead, Hersh wanted to present American conservatism as a unique ideology on its own terms.

He ultimately organized his course around big, intense political topics such as religion, guns, crime, and affirmative action, using readings pulled from sources as un-Tufts-like as the National Review, the Heritage Foundation, the Claremont Institute, and the Washington Examiner. In one class, he will deploy the projection screen and show a 15-minute Tucker Carlson monologue that aired on Fox News in 2019. For my part, I decided to take this ride with him to see how generally left-leaning students at a progressive college digest conservative thought, which is how I ended up the oldest person in a roomful of Gen Zers on a warm September day.

Hersh’s 13-week class won’t offer liberal rebuttals to conservative philosophies, mostly because students will find those voices elsewhere. He doesn’t devote much time to the backgrounds of the writers of the readings either. It’s the ideas he’s after.

Still, if there’s concern that American college students are being unduly steeped in liberal thinking to the detriment of society, then people like Ackman should be pleased to know that by 10:35 a.m., Hersh’s lecture room is pretty much full. Dozens of kids sitting all around me in Barnum Hall are apparently eager for a little taste of conservative ideology. A surprising number of them are freshmen.

But what really gets me on campus twice a week this fall is something Hersh told me after teaching his inaugural conservatism course last spring. His students confided in him that while inside his classroom, they felt freer to talk about contentious issues than anywhere else. By introducing a refreshingly contrary perspective, in this case conservative thought, Hersh believes he is somehow taking a lot of the emotional heft out of America’s most gut-wrenching topics and forcing students to find new intellectual muscles to process the right-leaning take.

On that note: Hersh hates the so-called language police. He believes campus rhetoric has evolved to protect students’ feelings and identities to such an extent that it’s nearly impossible to have an honest debate about almost anything. No one wants to hurt anyone else’s feelings. Perhaps somewhat ironically, on the first day of class, Hersh issues a “trigger warning.” He tells students to expect conversations about intense political issues, and while everyone has “hateful thoughts” from time to time, the spirit of the class is to foster genuine discussion and curiosity. To achieve that, he advises the students to ease up on language policing. “Give each other wiggle room,” he cautions, “because as you try to articulate a position, at first, it may come out wrong.”

I sense the excitement in the room as we try to imagine exactly what this might look like. Will the brutally honest conversations cause our perspectives and politics to shift? Will the class devolve into a “productive failure,” as Hersh warns us it might? To find out, and to track how these ideas are shaping undergrads, I plan to follow a few students closely as we take this journey together. And if what Hersh told me turns out to be true, we all might find that Barnum 104 is the safest place for free discourse on any college campus in America.

Tufts campus. / Photo by Jenna Schad/Tufts University

Like the Book of Genesis, Hersh’s course begins with a reckoning of good and evil. He drops us straight into the Cold War, where American conservatism is being birthed. The atomic bomb has just leveled two Japanese cities, and the power to annihilate another nation is suddenly looming large, stoking existential angst and nihilism. Fascism, after sweeping across Europe like a tsunami and bringing widespread death and destruction, now only persists in Portugal and Spain. Stateside, though, democracy feels fragile. Joseph McCarthy is swigging whiskey and routing out communists in the center ring; Ayn Rand is publishing a bestseller that lays out the case for rational egoism; and William F. Buckley Jr. is penning an editorial for the inaugural issue of his brand-new periodical, the National Review.

The next week, discussions go deeper. After setting the stage, Hersh lays out the fundamental dichotomy between conservative and liberal thought. Conservatives tend to believe that people spend their lives resisting the pull of temptation—the snake in the garden—and need clear rules to keep them in line (and clear repercussions when they stray). Liberals, on the other hand, believe that people, when given the luxury of choice, are inclined to do the right thing, which is why they tend to support policies designed to reduce inequality and unfairness and give people the ability to act morally.

Hersh draws from social-science research to explain how our morality spins out from there. When deciding whether a policy or action is right or wrong, liberals focus on questions of fairness. They want rewards and punishments to be meted out equitably, and they want to mitigate harm to particular groups. Conservatives, though, use considerably more metrics to process questions of morality. Some balance concerns of fairness and harm with ideas like loyalty to the system or authority. Will the action in question betray one’s country, family, or community? If so, it’s amoral. Conservatives also care a lot about duty—to one’s elders, to God, and to the wisdom of the ages that has shaped our laws and culture.

Interestingly, Hersh tells the class, our political leanings can affect our own happiness. He trots out a social-science study that suggests that conservatives are generally more content in their lives than liberals.

Hersh anticipates what many of the students are thinking—that conservatives’ apparent happiness comes from naiveté or a lack of compassion for those who might be victims of the world’s injustices. “As it turns out,” Hersh says, “that’s not the story.” Instead, the study shows, conservatives take comfort in rules because they give them the sense they have more control over their fates.

Here’s how that can play out in real life. “What are your parents hopes and dreams for you?” Hersh asks the class.

“Just to be happy,” a student says.

“Follow your passions.”

“They want me to be whoever I want to be.”

Some say their parents want them to be successful at whatever job they choose.

“I would never say any of those things about my children,” Hersh responds. He says he wants his children “to serve their family and community. I want them to follow the precepts of religion.” Hersh attends an Orthodox synagogue and, in his spare time—which is minimal since he commutes to Medford from Newton and splits childcare duties with his wife—enjoys listening to a podcast of conservative rabbis around the globe debating current events and esoterica through Halacha, or Jewish law. While he admits he may be a flawed father, “that mentality is going to make them happy because it’s giving them that sense of purpose and efficacy.” When you have a “God-given purpose of what I’m supposed to do and what my parents expect from me,” he adds, you’ll be happier.

That may be the case, but other factors are shaping how these students think about what roles they will play in society and where they will find satisfaction and happiness. The past few years have made a big impression on them. On their iPhones, they have the horrors of the world in their hands. They’ve witnessed real-life, unedited murder perpetrated by the police. They’ve seen countless school shootings. And after bearing witness to grand expressions of anger, hate, and frustration in this country, a good number of them have become exquisitely sensitive to how systems of authority oppress certain groups. Many have concluded that when an underrepresented underclass gets fed up with the status quo, violence is inevitable and may even be justified.

Outside of class, when I ask some students to list their top concerns, few mention traditionally liberal topics: climate change, the global rise of authoritarian governments, or supporting working people. Instead, they uniformly tell me that they arrived at Tufts with laser-like concern over rights—gay rights, trans rights, abortion rights. They believe more explicit rights will protect oppressed classes, which would go a long way toward making the United States a safer place for all people.

Predictably, one student in class points out that if you live in a conservative community and your values diverge but you’re forced to adhere to its strict religious tenets, then you’re bound for a life of sadness. That’s what another student named Sorsha is thinking because she lived it. When she was little, the freshman from L.A. with Native American heritage attended an evangelical Christian school, where she was taught that religion and politics were inseparable—a vote for Obama meant that you were a terrible person. Later, when she moved to public school and studied biology, which contradicts creationism, her grandparents told her that she wasn’t a Christian. “It was very much like if you don’t believe everything, then you don’t believe it at all,” she remembers. That, Sorsha says, “really ostracized me from religion.” During the COVID shutdowns, “in that isolated bubble,” she says, “I just kept getting further away from the idea that religion should have any part of politics—that conservatism was correct because that was what God wanted.”

Sorsha tells me that she “definitely identifies as liberal” but then tempers her assessment. “I don’t know how liberal I am, because my background is crazy,” she says, which is why she’s taking Hersh’s class. Eventually, she admits that she’s “more anti-evangelical conservative than I am for liberalism.”

After just a few weeks of taking Hersh’s class, though, Sorsha feels that she’s gaining more perspective on the choices her own family members made, which makes her hopeful that she can reconnect with them when she goes home for Christmas break. She’s learned that conservatives want to conserve things, she tells me; they’re resistant to change, wary of social experiment, and rely on the wisdom of the ages, which “feels like a lot of Native Americans. They want to preserve whatever they have left. Change is very scary because there’s already so much that’s gone.”

Likewise, Catie, a sporty, blond freshman who grew up in the Northeast and moved to Florida in high school, struggles to define her political leanings. She says she’s pro-choice and wants to speak for those who can’t advocate for themselves and “try to make a little bit more of a level playing field.” Still, she adds, she believes in free-market capitalism and understands the desire to roll back some regulation. She says that her mother, who works in the sports industry, is “about as moderate as you can get,” meaning culturally liberal, fiscally conservative. Her lawyer father is “pretty conservative” and believes in “very small government and less taxes.”

I’m beginning to realize that while many Tufts students call themselves liberal, it’s a tempered liberalism—one that respects the systems that secure wealth and power while nudging America closer to a more-equitable nation where fewer people might suffer from systemic injustices. They also tend to see right and wrong through the very narrow lens of oppressor versus oppressed. And in just a few weeks, this predilection for the oppressor-oppressed narrative on American college campuses will play out in explosive ways.

Back in class, the idea that rules engender happiness gnaws at the students, some of whom begin to see how a conservative upbringing could be beneficial. Maybe they would have been more secure if someone had given them marching orders. “I wake up each morning,” one male student says, and “I have no idea what I’m going to do. And I think that’s what leads to unhappiness, not knowing what comes next.”

The Tufts students tend to see right and wrong through the narrow lens of oppressor versus oppressed. And in just a few weeks, this predilection for that narrative on American college campuses will play out in explosive ways.

Hersh’s course is engineered to challenge students’ most basic understanding of their political beliefs, and now we’re going to talk about race. Are Black Americans oppressed by systemic racism? If so, what’s the proper correction?

To start off the discussion, Hersh introduces “The Case for Black Patriotism,” a 2022 essay by Glenn Loury. The Black economics professor at Brown argues that blaming systemic racism for the many issues Black Americans continue to face—including the high rate of Black-on-Black crime in the United States, the lower education levels achieved in the Black community, and the fact that some 70 percent of Black children are born to unwed mothers—fails to acknowledge the agency that Black people have over their own communities. Loury doesn’t deny that historical racism has impeded their ability to thrive, but he says that by harping on concepts such as white fragility and critical race theory, liberals are alienating Black citizens from their own country—the same country that fought for, and won, their emancipation. “Is this a good country,” Loury asks in his essay, one that offers boundless opportunity? “Or is it a venal, immoral, and rapacious bandit-society of plundering racists?” He argues the former, citing the fact that more than a century and a half after the legal end of slavery, America now boasts a huge Black middle class whose members are far wealthier than, say, modern Nigerians.

Loury claims that Black Americans have been conditioned by liberals to see only inequality rather than opportunity, a psychologically destructive narrative. Instead, Loury wants Black Americans to take responsibility for their own communities. Black people, he writes, need to “realize that white people cannot give us equality…. Today’s question [for Black Americans] is not how to end our oppression. It is what we will do with our freedom.”

Many white students immediately challenge Loury’s ideas, particularly his assertion that governmental institutions, including the criminal justice system, don’t cause irreparable harm. “When you put people in prison for a long time, it makes it hard to build community and wealth,” one says. “The policies are actively tearing down communities.”

Another student reverts to the language of fairness. “[Loury] is saying that we have to unlearn this idea that America isn’t for Black people. And that just seems like…that’s not fair in any way, shape, or form.” Says yet another student, “I think there are two explanations [for the data Loury cites]. It’s either that it’s inherent to being Black or Black culture, or there’s some sort of external force that’s causing people to commit crime, like socioeconomic status.”

But Loury isn’t arguing that historical racism doesn’t exist, Hersh says. His question is, how do we fix it?

A Black student in the front row seizes on Loury’s position: Liberals didn’t come up with the idea of systemic oppression themselves. “[The Black community] was already having our own conversation,” he says. They’ve merely co-opted and amplified it. And why would that be? Loury, for his part, argues that Black votes are being courted through the “gross exaggeration” of legitimate concerns.

All of this leaves the students questioning their understanding of social justice. Here we have at least one Black intellectual arguing that liberal ideology—one built around notions of institutional harm and victimhood—will never raise up communities. Rather, people need the strength of will to help themselves to overcome injustices of the past. If Loury’s position is correct, that this oppressor-oppressed narrative is harming the Black community while fueling the backlash (a.k.a. white nationalism), then it’s no longer useful.

So where does that leave Tufts’ young social justice warriors?

Hersh is working to counteract what he sees as a dearth of conservative thought on the Tufts campus with his highly popular lecture classes on American conservatism. / Photo by Tony Luong

At the end of the month, Hersh gets a real-life opportunity to test students’ understanding of conservative ideas following an on-campus protest by pro-choice students. On September 29, Tufts’ chapter of the Federalist Society, a national conservative and libertarian organization, held an in-person discussion between two male professors over the morality of abortion. Maybe that was in poor taste, given the recent U.S. Supreme Court ruling that left many pro-choice students feeling blindsided, but as an official Tufts organization, the FedSoc unquestionably had the right to hold the event, yes?

And protesters had the right to protest, no?

On the evening of the event, pro-choice Tufts students “frequently interrupted the speakers” with noisemakers playing the sounds of boos and cars honking, the Tufts Daily reported. The protesters kept at it even after campus police arrived. Only after a second officer showed up 45 minutes into the event did the disruptions stop.

After the incident, Hersh asks his students whether they thought the protesters had the right to disrupt the event. The classroom falls silent as they consider the question. Was protesting a right? If it was, who granted that right? Should there be consequences for the protesters?

He assures the class that there are no right or wrong answers, although I already know where he stands in the debate because we’ve had conversations about it outside of the classroom. Hersh’s teaching assistant is the president of Harvard Law School’s Federalist Society, and Hersh has sympathy for the Tufts chapter members, who sought him out as an adviser after the incident. Hersh feels that the protesters were essentially censoring speech by disrupting a pedagogical event, which is fundamentally anti-intellectual.

In class, students shift in their seats and look around uncomfortably. One pro-choice Tufts student says that the protesting wasn’t the issue—they had a right to state their views. It was how they protested. The pro-choice faction shouldn’t have been “so disruptive and inappropriate at an event like that,” she says.

Hersh continues his line of questioning. Doesn’t the school need stronger laws to protect intellectual discourse? Isn’t that the point of higher education?

“So what’s the appropriate penalty?” Hersh asks.

“I think maybe they should just get kicked out of the event,” she replies.

“So no consequence,” Hersh says.

Another student takes the position that the protesters had prevented people they disagreed with from expressing their views, which violated the academic ideal and prevented the careful consideration of a broad range of perspectives. “These [abortion] discussions are happening outside of Tufts every single day,” she says. “They’re happening on the national stage. They’re happening in communities. If they don’t happen in Tufts, then I think we’re missing out on a crucial part of learning, a crucial part of perspective, whether these people are male or female.” Still, she adds, she doesn’t think the school should have a punitive policy about protest, because she worries about the “slippery slope.”

Hersh looks for another point of view. A male student comes out more forcefully for consequences for the protesters: “Shutting down points of view…simply because you disagree with them is a punishable sort of offense. And I don’t know what a punishment will necessarily look like, but there should be something beyond removal.”

Hersh seems pleased that at least one student can see things another way.

So far, this is great fodder for a class on American conservatism: possible crimes, possible punishments, free speech, and campus politics. But when Hamas militants attack Israel on October 7, campuses across America will devolve into chaos. Barnum 104 will not be spared.

Today, Room 104 in Barnum Hall is quiet. But when Hersh’s students are present, it’s filled with the sounds of spirited debate. / Photo by Tony Luong

A few days after the attack, Hersh arrives to class visibly disheveled. Most people in his community are in shock at the scale of violence and death perpetrated against Israeli civilians. Hersh says he hasn’t slept and didn’t shave. He keeps his hat on throughout the entire class because he forgets he’s wearing it.

Continuing our exploration of rights and rules, today he wants to talk about an email sent by the Students for Justice in Palestine (SJP) celebrating the Hamas attack for its “creativity” in its attempt to “take back stolen land,” while mourning the loss of hundreds of Palestinian martyrs “fighting to liberate themselves and their land.”

Hersh tells the class, “We have a campus organization embracing and celebrating jihadi violence, murder, and rape against civilians, and I wanted to give space in case there was a member of SJP who’s here and wants to share some thoughts about whether we are okay with this campus organization, whether this amounts to hate speech, whether this amounts to our community norms.”

The same Black student in the front row who raised a hand the other day does so again. “For 75 years, Israel has been doing the same thing and nobody cared. So why do we care now? Did we suddenly care about women and children being raped and killed? I didn’t realize we had.” He begins to clap to emphasize each word: “It’s only when white people are raped and killed, but we don’t care when people of color are raped and killed.”

“Sorry,” Hersh says, “who are the white people in this story? Most Jews are not white in Israel.”

The student pauses, confused. “But they’re associated with whiteness,” he finally says. “They’re considered white in the United States.”

“Are you talking about skin tone here?” Hersh asks him. “Is an Ethiopian Jew in Israel or America, is that person white? Or a refugee from Yemen or Morocco?”

“Race is really complicated because of the history of America,” the student falters, “but it’s more of a class that kind of signifies superiority. As long as you are viewed as superior to another group of people, in a sense, you are being viewed as white.”

Hersh redirects: “I’m trying to understand what the acceptable boundaries are for the community. Are we okay having jihad supporters, ISIS, KKK, on campus? If they threaten me and all of the Jewish students on campus, what should we do?”

He points out that many of the students in class were not comfortable restricting the speech of the pro-choice protesters on campus—now he wants to know if these students would restrict the expression of a far-left “group on campus wishing death to civilians.”

One student says he would. “[SJP] should have unilaterally and without question condemned what happened, and they didn’t,” the student says. “And for that reason, SJP should lose its club status because they’re supporting a terrorist group.”

That sends the student in the front row into a rage. He expresses his view that by oppressing the Palestinians, Israel forced Hamas to use violence and that righting systemic wrongs, in this case, justifies that violence. His voice is shaking and raw. “Soldiers in Jewish society have been raping and killing Palestinian children and women,” he says, adding that he believes no one has been held responsible. Now that the roles are reversed, we’re supposed to care?

Most students in the room are stunned into silence. Hersh suggests that the student come to office hours with credible documentation that supports his statement about Israeli soldiers. The student never follows up.

Are these the “hateful thoughts” Hersh warned us about at the start of the semester? Have we finally crossed the line?

Are these the “hateful thoughts” Hersh warned us about at the start of the semester? Have we finally crossed the line? If so, it feels good to get them out in the open in a structured environment where the class can lean on a knowledgeable guide. After all, these ideas are exploding all over social media unmediated in any way. Perhaps it’s healthy to hear them firsthand, to wrangle with them, in the safety of Barnum 104.

And indeed it appears these liberal-ish young adults, when steeped in contrasting ideologies, are becoming more thoughtful, more humanist. “If you are on the side of moral decency and humanity,” one student says, “then you ought to be able to call out hatred for what it is. Or have we gotten to the point where endorsing terrorism against ‘colonizers’ is something that is acceptable?”

A few days later, Hersh challenges these students again to think about their views on social justice. Justice is a process, Hersh says—a fair trial, an impartial judge—but social justice entails “[eliminating] undeserved disadvantages for selected groups,” according to Black economist Thomas Sowell, which is nearly impossible to accomplish. Hersh continues to cite Sowell, who argues that trying to achieve “cosmic justice” will inevitably cause harm elsewhere. In his essay “The Quest for Cosmic Justice,” Sowell makes the case that “when you try to do something good here,” Hersh summarizes, “you end up oftentimes having a lot of collateral damage over there…. It’s very complicated to figure out why people are disadvantaged.”

Remarkably, the students seem to see that now. “The way [American colonizers] acted was inherently flawed, inherently immoral,” one says, “but at the same time, you can’t make the argument that we should just blow everything up and go back to the way it was.”

That’s certainly a rational argument, Hersh says. Then he reminds us that way back in 1944, after watching the rise of the Nazis, the Austrian-British Nobel Prize–winning economist Friedrich Hayek understood exactly “how you can get from a social justice mentality focused on equality and justice to something that looks incredibly violent,” where any amount of death could be justified to achieve a goal.

The benefit of being able to speak openly in an academic setting is that students can process ideas with a few more intellectual tools. One month into this American conservatism course, it seems some students are more willing to consider a variety of possible viewpoints. While campuses across America will rapidly devolve into predominantly anti-Israel anger over the coming weeks, most students in this classroom are resisting the temptation to draw easy conclusions.

The front-row student now also has a nuanced take, which reveals precisely how influential these conservative ideas can be, and how brilliant young people can be when offered a range of viewpoints. The same person who was shaking with fury over the idea that we should have compassion for all victims of a horrendous situation has come around to the idea that maybe we shouldn’t strive to right all wrongs. Instead, he says, the goal of social justice should be “ensuring that a community doesn’t feel completely disenfranchised,” that true social justice should offer “routes other than violence,” which will allow people to “thrive in society. And in life.”

Is Hersh planting the seeds of a new liberal liberalism, an ideology that is more concerned with positive outcomes than righting historical wrongs? Significantly, this new liberalism could take hold if young people are given access to a full range of ideologies and perspectives. In other words, maybe, just maybe, Hersh is onto something.

First published in the print edition of the April 2024 issue with the headline, “A Radical Experiment at Tufts.”